Windowflage, part 1

The Coney Island Elephantine Colossus is an object lesson in the need for windowflage, the camouflaging of windows in the service of a building's overall sculptural effect. The work of Philadelphia architect William Free, it was built in 1883-85 as a hotel and later became a brothel. In 1896, it departed this world in true Coney Island style by burning down. Resolution of the conflict it illustrates, between form and fenestration, is one of the driving forces behind much recent architectural innovation on view in New York.

In his 1930 book, Precisions, Le Corbusier presented a series of sketches illustrating "the history of architecture by the history of windows throughout the ages," culminating with his own horizontal ribbon window. Much of the history of architecture since can be traced in the history of window camouflage.

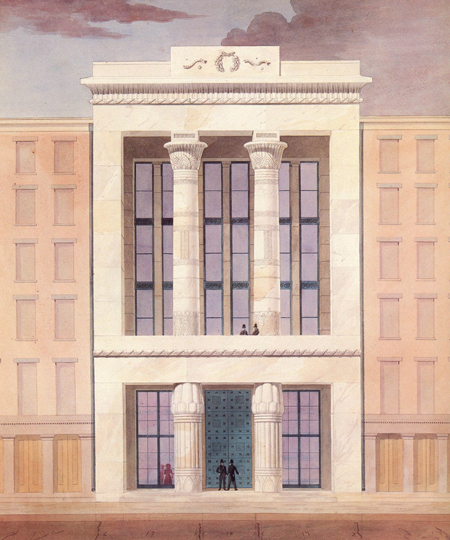

The 19th century New York architect Alexander Jackson Davis pioneered disguising of the individual window. According to Jane B. Davies in the 1992 Metropolitan Museum of Art monograph on the architect, "A remarkable original creation by Davis was the window he called Davisean Multistoried, recessed in one plane with a panel at floor level and usually with mullions running its height, it gave unity and verticality to a façade. It anticipated the modern vertical strip window. . . . Occasionally imitated by other architects, it was too far ahead of its time to be adopted generally."

In New York's great pre-war age of skyscrapers, the influential renderer Hugh Ferris and progressive architects like Raymond Hood carried Davis's vertical strip windows into the clouds.

The post-war development of the glass curtain wall created the opportunity for a uniform surface that made transparent and opaque panes appear the same from outside. Rebelling against the facile over-use of this technique, from suburban office parks to glitzy Trump towers, today's leading designers are finding new ways to resolve and even exploit the window-vs-object issue. Such solutions began and first developed in New York, and the city's newest notable buildings show how their continued pursuit has become a primary concern of today's architecture.

The Coney Island Elephantine Colossus is an object lesson in the need for windowflage, the camouflaging of windows in the service of a building's overall sculptural effect. The work of Philadelphia architect William Free, it was built in 1883-85 as a hotel and later became a brothel. In 1896, it departed this world in true Coney Island style by burning down. Resolution of the conflict it illustrates, between form and fenestration, is one of the driving forces behind much recent architectural innovation on view in New York.

In his 1930 book, Precisions, Le Corbusier presented a series of sketches illustrating "the history of architecture by the history of windows throughout the ages," culminating with his own horizontal ribbon window. Much of the history of architecture since can be traced in the history of window camouflage.

The 19th century New York architect Alexander Jackson Davis pioneered disguising of the individual window. According to Jane B. Davies in the 1992 Metropolitan Museum of Art monograph on the architect, "A remarkable original creation by Davis was the window he called Davisean Multistoried, recessed in one plane with a panel at floor level and usually with mullions running its height, it gave unity and verticality to a façade. It anticipated the modern vertical strip window. . . . Occasionally imitated by other architects, it was too far ahead of its time to be adopted generally."

In New York's great pre-war age of skyscrapers, the influential renderer Hugh Ferris and progressive architects like Raymond Hood carried Davis's vertical strip windows into the clouds.

The post-war development of the glass curtain wall created the opportunity for a uniform surface that made transparent and opaque panes appear the same from outside. Rebelling against the facile over-use of this technique, from suburban office parks to glitzy Trump towers, today's leading designers are finding new ways to resolve and even exploit the window-vs-object issue. Such solutions began and first developed in New York, and the city's newest notable buildings show how their continued pursuit has become a primary concern of today's architecture.

Alexander Jackson Davis's 1835 rendering shows an unbuilt New York project for an American Institute. The windows of its upper floors are arranged into continuous vertical strips, concealing their association with stacked floors, as is honestly expressed in the flanking buildings. Davis's windows suggest a single full-height space within and support the building's simulation of a cavernous Egyptian temple. His division of the facade into a street-level entry story and upper floors that read as a single volume is a continuing hallmark of buildings that camouflage windows.

Alexander Jackson Davis's 1835 rendering shows an unbuilt New York project for an American Institute. The windows of its upper floors are arranged into continuous vertical strips, concealing their association with stacked floors, as is honestly expressed in the flanking buildings. Davis's windows suggest a single full-height space within and support the building's simulation of a cavernous Egyptian temple. His division of the facade into a street-level entry story and upper floors that read as a single volume is a continuing hallmark of buildings that camouflage windows.

Either/Or: to the left of the Woolworth Building, a brick tower does nothing to reconcile its human-scaled windows to a city-scaled building; at far left, the Millenium Hotel tower dispenses with expressed windows altogether by way of a tinted glass curtain wall that makes the building pure sculpture. Both/And: The Woolworth Building achieves real architecture through a design that's both windowed building and sculpture.

Either/Or: to the left of the Woolworth Building, a brick tower does nothing to reconcile its human-scaled windows to a city-scaled building; at far left, the Millenium Hotel tower dispenses with expressed windows altogether by way of a tinted glass curtain wall that makes the building pure sculpture. Both/And: The Woolworth Building achieves real architecture through a design that's both windowed building and sculpture.

Architects of early skyscrapers had a new form and scale to deal with. Working from a toolbox of historical styles that were meant for lower buildings, they were at a loss until Cass Gilbert adopted the verticality of the Gothic to the Woolworth Building. Upon its completion in 1913, it was not just the world's tallest skyscraper, but the most successfully composed. Although its windows are internally related by common horizontal floors, Gilbert externally combined them in vertical strips that relate to the overall scale and vertical orientation of the building, to symphonic effect. A step had been taken toward the disappearance of the individual window.

Architects of early skyscrapers had a new form and scale to deal with. Working from a toolbox of historical styles that were meant for lower buildings, they were at a loss until Cass Gilbert adopted the verticality of the Gothic to the Woolworth Building. Upon its completion in 1913, it was not just the world's tallest skyscraper, but the most successfully composed. Although its windows are internally related by common horizontal floors, Gilbert externally combined them in vertical strips that relate to the overall scale and vertical orientation of the building, to symphonic effect. A step had been taken toward the disappearance of the individual window.

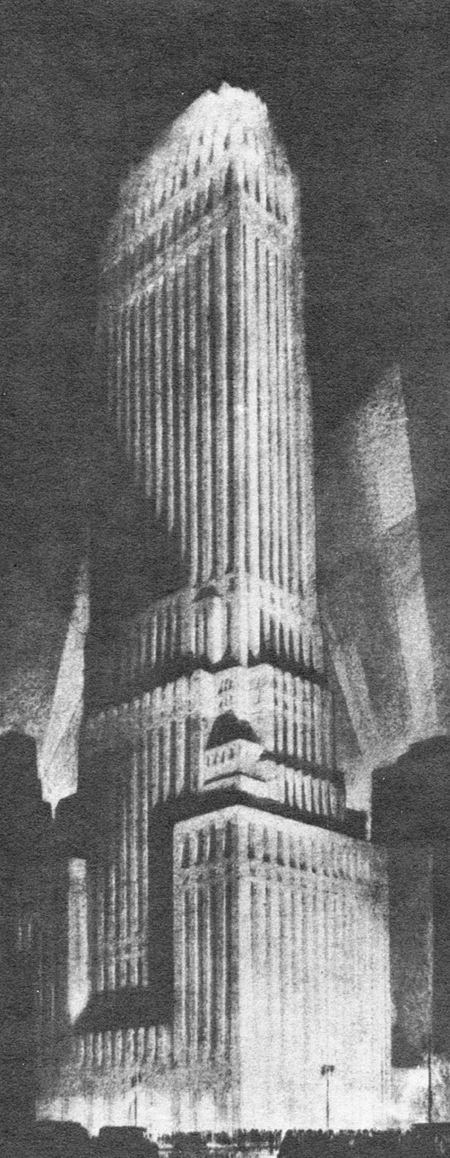

A rendering by Hugh Ferris shows the Chanin Building, built 1927-29. By this time, the vertical organization of windows pioneered by the Woolworth building had become the norm. Ferriss's rendering dispenses with individual windows altogether, showing only the vertical recesses into which they would be organized.

A rendering by Hugh Ferris shows the Chanin Building, built 1927-29. By this time, the vertical organization of windows pioneered by the Woolworth building had become the norm. Ferriss's rendering dispenses with individual windows altogether, showing only the vertical recesses into which they would be organized.

A rendering from Hugh Ferriss's 1929 book, The Metropolis of Tomorrow, shows an imaginary, windowless building: "Buildings like crystals. Walls of translucent glass. Sheer glass blocks sheathing a steel grill." His vision anticipated glass curtain wall technology that was still decades away. The crystalline forms he imagined are as current as Cook + Fox Architects' Bank of America Tower, completed in 2008, and Jean Nouvel's proposed MoMA Tower.

A rendering from Hugh Ferriss's 1929 book, The Metropolis of Tomorrow, shows an imaginary, windowless building: "Buildings like crystals. Walls of translucent glass. Sheer glass blocks sheathing a steel grill." His vision anticipated glass curtain wall technology that was still decades away. The crystalline forms he imagined are as current as Cook + Fox Architects' Bank of America Tower, completed in 2008, and Jean Nouvel's proposed MoMA Tower.

Completed in 1924, Raymond Hood's first New York skyscraper was the American Radiator Building at 40 West 40th Street, overlooking Bryant Park. Hood suppressed the appearance of countless windows as he would in all the great skyscrapers he went on to design. In this case, his choice of brick color downplayed windows to emphasize masterful building massing. (This tactic is undercut by the current management's use of white window treatments.) "If the black windows punched the relatively light colored masonry exterior full of holes, the thing to do was to make the walls black so the windows wouldn't show." - Raymond Hood Architect, by Walter H. Kilham, 1973.

Completed in 1924, Raymond Hood's first New York skyscraper was the American Radiator Building at 40 West 40th Street, overlooking Bryant Park. Hood suppressed the appearance of countless windows as he would in all the great skyscrapers he went on to design. In this case, his choice of brick color downplayed windows to emphasize masterful building massing. (This tactic is undercut by the current management's use of white window treatments.) "If the black windows punched the relatively light colored masonry exterior full of holes, the thing to do was to make the walls black so the windows wouldn't show." - Raymond Hood Architect, by Walter H. Kilham, 1973.

Raymond Hood's Daily News Building, built 1929-30, took Hugh Ferris's suppression of windows into dark vertical recesses a step closer to reality, even as it abstracted skyscraper massing and detail into new territory. Ferris rendered several of Hood's projects and his simplifying style was in turn so influential on architects that Rem Koolhaas wrote in Delirious New York, "the city would establish him, Ferriss the renderer, as its chief architect . . ."

Raymond Hood's Daily News Building, built 1929-30, took Hugh Ferris's suppression of windows into dark vertical recesses a step closer to reality, even as it abstracted skyscraper massing and detail into new territory. Ferris rendered several of Hood's projects and his simplifying style was in turn so influential on architects that Rem Koolhaas wrote in Delirious New York, "the city would establish him, Ferriss the renderer, as its chief architect . . ."

Hood switched to continuous horizontal bands of windows in the McGraw-Hill Building, built 1930-1931. These allowed greater flexibility of interior layout and reflected Le Corbusier's ideas about modern "landscape" oriented windows. In this Hood-commissioned photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, the building's flush-set windows become lost amid the reflective glazed terra cotta building skin, and the simple force of the building's massing predominates. Gottscho contrasts Hood's taut, polished, machine-age surface to the punched windows of the older building in the foreground. Like Hugh Ferriss's renderings of crystalline buildings, this image anticipates the post-war glass curtain wall technology that would subdue and even obliterate expression of the window.

Hood switched to continuous horizontal bands of windows in the McGraw-Hill Building, built 1930-1931. These allowed greater flexibility of interior layout and reflected Le Corbusier's ideas about modern "landscape" oriented windows. In this Hood-commissioned photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, the building's flush-set windows become lost amid the reflective glazed terra cotta building skin, and the simple force of the building's massing predominates. Gottscho contrasts Hood's taut, polished, machine-age surface to the punched windows of the older building in the foreground. Like Hugh Ferriss's renderings of crystalline buildings, this image anticipates the post-war glass curtain wall technology that would subdue and even obliterate expression of the window.

Carried to its logical conclusion, windowflage finds a dead end in the black glass curtain wall of Trump World Tower, designed by Donald Trump's house architect, Kostas Condylis. The world's tallest residential building upon its completion in 2001, the best anyone could find to say about it was that it wasn't gold. Other architects have sought more satisfying solutions to the conflict between form and fenestration, and their pursuit has made for much of New York's best recent architecture.

continued

Carried to its logical conclusion, windowflage finds a dead end in the black glass curtain wall of Trump World Tower, designed by Donald Trump's house architect, Kostas Condylis. The world's tallest residential building upon its completion in 2001, the best anyone could find to say about it was that it wasn't gold. Other architects have sought more satisfying solutions to the conflict between form and fenestration, and their pursuit has made for much of New York's best recent architecture.

continued

Subscribe Us

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a selection of cool articles every weeks