Architecture Meets Science Fiction at 41 Cooper Square

Thom Mayne's new academic building for Cooper Union, 41 Cooper Square, is the Pritzker Prize winning architect's first building in New York. Sensual, jarring and willfully strange, it's unlike anything else in the city. New Yorkers won't find a meaningful introduction to Mayne or his building anywhere in the popular press.

Fifteen years ago, a Progressive Architecture editorial by Thomas Fisher titled "A House Divided" lamented the state of writing about architecture. Fisher saw a choice between "unquestioning description" by architectural journalists and "obscure, jargon-filled analysis" by academic critics. "What is rare, on either side," Fisher wrote, "are critics who can address the underlying ideas and larger meanings of architecture and who can convey them clearly and concisely to the public and the profession." What's been written so far about Thom Mayne's new academic building for Cooper Union shows how true this remains.

On the journalism side, Joann Gonchar, in last month's Architectural Record cover story about the building, mainly limited herself to description, calling it "extroverted," "sharp and folded," "aggressive," "dynamic," "gutsy," and "energetic." She might have been describing Marcel Breuer's 1966 Whitney Museum uptown. No more helpful was Nicolai Ouroussoff in the New York Times, with his effusions about "a bold architectural statement of genuine civic value," with "a bold, aggressive profile" and "a brash, rebellious attitude," "tough and sexy at the same time." While any criticism of a challenging building by a renowned architect puts the critic at risk of looking unenlightened, it's less like 41 Cooper Square is being handled with kid gloves than oven mitts. The building Mayne and his firm Morphosis have landed at 41 Cooper Square has been widely written up as a "spaceship" with a swoopy stair atrium that brings students together, but we're left on our own as to where such an alien presence came from, what its terms are and whether it succeeds on them.

On the academic criticism side, 41 Cooper Square is covered in Volume 4 of Rizzoli's Morphosis series. The book's introduction, by Mayne, and most of the ten essays contributed by architects and critics punish any attempt to read them. Take Mayne's high-flown, obscure and flaccid description of his quest for an architecture "capable of providing the generative material for new trajectories, methods, and outputs that add further to a coherent complexity that I so strive for." One wants to bounce a copy of George Orwell's "Politics and the English Language" (concrete good, abstract bad) off his high brow. Mayne's one-page project description for 41 Cooper Square later in the book is all a very safe, straightforward and reasonable justification of the building that completely avoids its distinguishing otherworldliness, the torn open facade, those unreadable folds and general strangeness. A rare readable insight is provided in the essay by Lebbeus Woods, who writes that "the buildings of Morphosis, with their questionings, their distortions of the known, with their unresolved, frankly exposed collisions of differences, are self-consciously incomplete. Their aesthetic is the opposite of what Alberti required of 'beauty, which is that to which nothing can be added; and that from which nothing can be taken away.' Beauty, as a reflection of divine perfection, was complete, eternal. In contrast, the buildings of Morphosis seem to crystallize, with sharpness and unflinching candor, precise, unique moments in time."

Thom Mayne's new academic building for Cooper Union, 41 Cooper Square, is the Pritzker Prize winning architect's first building in New York. Sensual, jarring and willfully strange, it's unlike anything else in the city. New Yorkers won't find a meaningful introduction to Mayne or his building anywhere in the popular press.

Fifteen years ago, a Progressive Architecture editorial by Thomas Fisher titled "A House Divided" lamented the state of writing about architecture. Fisher saw a choice between "unquestioning description" by architectural journalists and "obscure, jargon-filled analysis" by academic critics. "What is rare, on either side," Fisher wrote, "are critics who can address the underlying ideas and larger meanings of architecture and who can convey them clearly and concisely to the public and the profession." What's been written so far about Thom Mayne's new academic building for Cooper Union shows how true this remains.

On the journalism side, Joann Gonchar, in last month's Architectural Record cover story about the building, mainly limited herself to description, calling it "extroverted," "sharp and folded," "aggressive," "dynamic," "gutsy," and "energetic." She might have been describing Marcel Breuer's 1966 Whitney Museum uptown. No more helpful was Nicolai Ouroussoff in the New York Times, with his effusions about "a bold architectural statement of genuine civic value," with "a bold, aggressive profile" and "a brash, rebellious attitude," "tough and sexy at the same time." While any criticism of a challenging building by a renowned architect puts the critic at risk of looking unenlightened, it's less like 41 Cooper Square is being handled with kid gloves than oven mitts. The building Mayne and his firm Morphosis have landed at 41 Cooper Square has been widely written up as a "spaceship" with a swoopy stair atrium that brings students together, but we're left on our own as to where such an alien presence came from, what its terms are and whether it succeeds on them.

On the academic criticism side, 41 Cooper Square is covered in Volume 4 of Rizzoli's Morphosis series. The book's introduction, by Mayne, and most of the ten essays contributed by architects and critics punish any attempt to read them. Take Mayne's high-flown, obscure and flaccid description of his quest for an architecture "capable of providing the generative material for new trajectories, methods, and outputs that add further to a coherent complexity that I so strive for." One wants to bounce a copy of George Orwell's "Politics and the English Language" (concrete good, abstract bad) off his high brow. Mayne's one-page project description for 41 Cooper Square later in the book is all a very safe, straightforward and reasonable justification of the building that completely avoids its distinguishing otherworldliness, the torn open facade, those unreadable folds and general strangeness. A rare readable insight is provided in the essay by Lebbeus Woods, who writes that "the buildings of Morphosis, with their questionings, their distortions of the known, with their unresolved, frankly exposed collisions of differences, are self-consciously incomplete. Their aesthetic is the opposite of what Alberti required of 'beauty, which is that to which nothing can be added; and that from which nothing can be taken away.' Beauty, as a reflection of divine perfection, was complete, eternal. In contrast, the buildings of Morphosis seem to crystallize, with sharpness and unflinching candor, precise, unique moments in time."

Thom Mayne's architecture acknowledges the imperfection and fragmentary nature of a dynamic world that's never complete, attested to in this picture's foreground. 41 Cooper Square's veil of perforated stainless steel is a stock Morphosis feature, justified as an energy saver although it's highly doubtful that the shading it provides improves much on today's low-heat-gain glazing or makes up for the reduction in natural light it incurs, particularly to the north. Given natural light's proven enhancement of learning ability, this is no small sacrifice in a building that contains classrooms. Sections of the skin can be opened to admit more light, but putting up a barrier just to have to overcome it seems impractical. Claims that the veil will "retain heat in winter" are preposterous. While the building is in fact highly energy efficient, the stated rationale for the veil is merely what must be told to a client's building committee members. (Saying it's just there for expression would be like telling them the facts of life instead of the stork story before they're ready. Such folks are so grateful for a shred of justification to cover their backsides, they'll take anything: Mayne actually claims his Hypo Alpe-Adria Bank tower in Udine, Italy, leans 14 degrees to the south in order to shade itself, the equivalent in practicality of digging a tunnel to cross the street.) The veil's real purpose is to suppress the appearance of windows in favor of the building's overall sculptural effect, a strategy at least as old as Raymond Hood's use of black brick on the 1924 American Radiator Building to make its dark window openings blend in and disappear. In place of the usual window pattern, the veil's random solid rectangular bits emphasize its contours while suggesting an alien information code, or simply celebrating resistance to order. A public that no longer has a clue what architects are getting at may simply shrug off any confusion and welcome its undeniable beauty and the way it makes the world a more interesting place, as has been the case with Frank Gehry's IAC Building across town. Many in the architectural profession seem to resent this kind of response and see in such buildings a degrading emphasis on surface spectacle over substance. To them, Mayne's textile-like sheath with its raised hem may recall an expression for the most superficial approach to architecture, "putting dresses on buildings." Critics may see Mayne's building as no less permanent and composed than its neighbors, its imagery and encasing screen oppressive, and Mayne's liberator persona a pose.

It's telling that the clearest insight into Thom Mayne comes from Lebbeus Woods, the visionary architect and artist who has for several years been a professor of architecture at Cooper Union. Woods' work shares with Mayne's an antecedent in Archigram, the 1960s futurist group of British architects who published their theoretical projects in comic book style pamphlets. For Archigram, the city of the future would be a dynamic machine capable of constantly reconfiguring itself, built from movable, modular components that might be replaced with new models when obsolete, like cars and other industrial products. If this sounds like a radical concept, consider that the group established itself around the time of the demolition of New York's Pennsylvania Station, a building modeled on the Baths of Caracalla, built for the ages, and torn down in the path of new purposes only 53 years after its completion. Archigram's alternative was a kind of anti-architecture that anticipated a future in which change was the only certainty. Architecture's former emphasis on the monumental and permanent was jettisoned in favor of an ephemeral approach in keeping with the disposable culture of a new age and ever evolving technology. Where the architects of Penn Station clung to a view of an unchanging world in which a Roman ruin was a viable model, Archigram accepted a dynamic and unpredictable world and looked to the future for its style. And the look of the future was to be found in science fiction.

Interviewed in Yoshio Futagawa's 2002 book, Studio Talk, Mayne says that when he was a student, "UCLA had just started its architectural program, the Archigram boys were there, and I met Peter Cook, Warren Chalk and Ron Herron for the first time. They completely took over the place . . . Three years later we would borrow their concept of a collective practice, which led directly to the choice of the name Morphosis." Later in the interview, when asked his specific influences, Archigram is the first Mayne cites: "I think you will find that my generation lacks any unifying ideology . . . a result of both the exhaustion of the dogma of Modern architecture and the rapidly changing conditions, which have demanded a multiplicity of architectural positions. . . As I mentioned earlier, Archigram was important for me, encapsulating much of the 60s, all that is ephemeral." Mayne seems not just to have carried forward Archigram's sense of a world in transition, but, at least in 41 Cooper Square, the science fiction imagery that Archigram described as part of a "search for ways out from the stagnation of the architectural scene."

One might reasonably ask whether Mayne's use of science fiction imagery without the kind of futuristic innovation proposed by Archigram is anything more than PR. Referring to the huge commercial success of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, Lebbeus Woods has written that "the 'Bilbao Effect' has dampened critical architectural writing. With its advent, interest shifted from the heady quarrels about Deconstructism and Post-Modernism to a concern with the much less intellectually taxing search for novel forms. Novel forms work so well, from the viewpoint of promoting tourism and other spun-off enterprises. As for the Bilbao Guggenheim, there’s not much that can be said about it beyond its great success. It encloses the same old museum programs. If we look behind the curving titanium skin, we find swarms of metal studs holding it up—no innovative construction technology there. It hasn’t inspired a new architecture, or a new discourse, other than that of media success."

Many other architects today are dismayed by what they see as an increasingly superficial direction in the profession, toward styling above content, image above the kind of substantial ideas, like Palladio’s, Corbusier’s or Kahn’s, that can be built upon by others. This emphasis on image is easy to construe as a reflection of an increasingly shallow, short attention-span culture. The architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable describes ”a public increasingly desensitized by today’s can-you-top-this hypersensationalism and the expectation of in-your-face ‘icons’.” Would Huxtable lump Thom Mayne’s work in this category? Apparently not. As a member of the jury that awarded him architecture’s highest honor, the Pritzker Prize, in 2005, she stated that ”the work of Thom Mayne moves architecture from the 20th to the 21st century in its use of today’s art and technology to create a dynamic style that expresses and serves today’s needs.” In fact, few high-profile architects have pushed the envelope of sustainability and mechanical system innovation as far as Mayne has. If his work seems pretentious in its exptessionism, Mayne’s supporters would argue that it earns its pretensions in a relentlessly questioning, self-critical design process, genuine enthusiasm for sustainability and real technical advancement. In other words, Mayne gets his homework done and still has time to play. It’s all icing that his play can convince us of the possibility of new realities.

Thom Mayne's architecture acknowledges the imperfection and fragmentary nature of a dynamic world that's never complete, attested to in this picture's foreground. 41 Cooper Square's veil of perforated stainless steel is a stock Morphosis feature, justified as an energy saver although it's highly doubtful that the shading it provides improves much on today's low-heat-gain glazing or makes up for the reduction in natural light it incurs, particularly to the north. Given natural light's proven enhancement of learning ability, this is no small sacrifice in a building that contains classrooms. Sections of the skin can be opened to admit more light, but putting up a barrier just to have to overcome it seems impractical. Claims that the veil will "retain heat in winter" are preposterous. While the building is in fact highly energy efficient, the stated rationale for the veil is merely what must be told to a client's building committee members. (Saying it's just there for expression would be like telling them the facts of life instead of the stork story before they're ready. Such folks are so grateful for a shred of justification to cover their backsides, they'll take anything: Mayne actually claims his Hypo Alpe-Adria Bank tower in Udine, Italy, leans 14 degrees to the south in order to shade itself, the equivalent in practicality of digging a tunnel to cross the street.) The veil's real purpose is to suppress the appearance of windows in favor of the building's overall sculptural effect, a strategy at least as old as Raymond Hood's use of black brick on the 1924 American Radiator Building to make its dark window openings blend in and disappear. In place of the usual window pattern, the veil's random solid rectangular bits emphasize its contours while suggesting an alien information code, or simply celebrating resistance to order. A public that no longer has a clue what architects are getting at may simply shrug off any confusion and welcome its undeniable beauty and the way it makes the world a more interesting place, as has been the case with Frank Gehry's IAC Building across town. Many in the architectural profession seem to resent this kind of response and see in such buildings a degrading emphasis on surface spectacle over substance. To them, Mayne's textile-like sheath with its raised hem may recall an expression for the most superficial approach to architecture, "putting dresses on buildings." Critics may see Mayne's building as no less permanent and composed than its neighbors, its imagery and encasing screen oppressive, and Mayne's liberator persona a pose.

It's telling that the clearest insight into Thom Mayne comes from Lebbeus Woods, the visionary architect and artist who has for several years been a professor of architecture at Cooper Union. Woods' work shares with Mayne's an antecedent in Archigram, the 1960s futurist group of British architects who published their theoretical projects in comic book style pamphlets. For Archigram, the city of the future would be a dynamic machine capable of constantly reconfiguring itself, built from movable, modular components that might be replaced with new models when obsolete, like cars and other industrial products. If this sounds like a radical concept, consider that the group established itself around the time of the demolition of New York's Pennsylvania Station, a building modeled on the Baths of Caracalla, built for the ages, and torn down in the path of new purposes only 53 years after its completion. Archigram's alternative was a kind of anti-architecture that anticipated a future in which change was the only certainty. Architecture's former emphasis on the monumental and permanent was jettisoned in favor of an ephemeral approach in keeping with the disposable culture of a new age and ever evolving technology. Where the architects of Penn Station clung to a view of an unchanging world in which a Roman ruin was a viable model, Archigram accepted a dynamic and unpredictable world and looked to the future for its style. And the look of the future was to be found in science fiction.

Interviewed in Yoshio Futagawa's 2002 book, Studio Talk, Mayne says that when he was a student, "UCLA had just started its architectural program, the Archigram boys were there, and I met Peter Cook, Warren Chalk and Ron Herron for the first time. They completely took over the place . . . Three years later we would borrow their concept of a collective practice, which led directly to the choice of the name Morphosis." Later in the interview, when asked his specific influences, Archigram is the first Mayne cites: "I think you will find that my generation lacks any unifying ideology . . . a result of both the exhaustion of the dogma of Modern architecture and the rapidly changing conditions, which have demanded a multiplicity of architectural positions. . . As I mentioned earlier, Archigram was important for me, encapsulating much of the 60s, all that is ephemeral." Mayne seems not just to have carried forward Archigram's sense of a world in transition, but, at least in 41 Cooper Square, the science fiction imagery that Archigram described as part of a "search for ways out from the stagnation of the architectural scene."

One might reasonably ask whether Mayne's use of science fiction imagery without the kind of futuristic innovation proposed by Archigram is anything more than PR. Referring to the huge commercial success of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, Lebbeus Woods has written that "the 'Bilbao Effect' has dampened critical architectural writing. With its advent, interest shifted from the heady quarrels about Deconstructism and Post-Modernism to a concern with the much less intellectually taxing search for novel forms. Novel forms work so well, from the viewpoint of promoting tourism and other spun-off enterprises. As for the Bilbao Guggenheim, there’s not much that can be said about it beyond its great success. It encloses the same old museum programs. If we look behind the curving titanium skin, we find swarms of metal studs holding it up—no innovative construction technology there. It hasn’t inspired a new architecture, or a new discourse, other than that of media success."

Many other architects today are dismayed by what they see as an increasingly superficial direction in the profession, toward styling above content, image above the kind of substantial ideas, like Palladio’s, Corbusier’s or Kahn’s, that can be built upon by others. This emphasis on image is easy to construe as a reflection of an increasingly shallow, short attention-span culture. The architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable describes ”a public increasingly desensitized by today’s can-you-top-this hypersensationalism and the expectation of in-your-face ‘icons’.” Would Huxtable lump Thom Mayne’s work in this category? Apparently not. As a member of the jury that awarded him architecture’s highest honor, the Pritzker Prize, in 2005, she stated that ”the work of Thom Mayne moves architecture from the 20th to the 21st century in its use of today’s art and technology to create a dynamic style that expresses and serves today’s needs.” In fact, few high-profile architects have pushed the envelope of sustainability and mechanical system innovation as far as Mayne has. If his work seems pretentious in its exptessionism, Mayne’s supporters would argue that it earns its pretensions in a relentlessly questioning, self-critical design process, genuine enthusiasm for sustainability and real technical advancement. In other words, Mayne gets his homework done and still has time to play. It’s all icing that his play can convince us of the possibility of new realities.

A cutaway model of 41 Cooper Square shows its stair atrium as a free-form invader of an otherwise conventional interior of straw man "square" spaces. It seems to embody Lebbeus Woods' statement, "I am at war with all authority that resides in fixed and frightened forms." No one has written more lucidly about Mayne than Woods. In his essay endorsing Mayne's Pritzker Prize, Woods wrote that "Mayne's method of design confronts the typical with the strange, the program with the architecture. Far from being arbitrary, self-expressive exercises, these confrontations of the formal with the contingent emerge from the necessity to change the ways we think and act. They are challenges to the conventional stereotypes and heirarchy, but ones that actively enable them to evolve, rather than be discarded or overturned. The point is, this enablement cannot come about by simply tinkering with the typologies, but only by confronting them with something new, unfamiliar, that comes from outside." 41 Cooper Square fills the bill, inside and out.

A cutaway model of 41 Cooper Square shows its stair atrium as a free-form invader of an otherwise conventional interior of straw man "square" spaces. It seems to embody Lebbeus Woods' statement, "I am at war with all authority that resides in fixed and frightened forms." No one has written more lucidly about Mayne than Woods. In his essay endorsing Mayne's Pritzker Prize, Woods wrote that "Mayne's method of design confronts the typical with the strange, the program with the architecture. Far from being arbitrary, self-expressive exercises, these confrontations of the formal with the contingent emerge from the necessity to change the ways we think and act. They are challenges to the conventional stereotypes and heirarchy, but ones that actively enable them to evolve, rather than be discarded or overturned. The point is, this enablement cannot come about by simply tinkering with the typologies, but only by confronting them with something new, unfamiliar, that comes from outside." 41 Cooper Square fills the bill, inside and out.

A rendering from Lebbeus Woods' 1990 "Berlin Free-Zone 3-2" project closely prefigures Mayne's stair atrium at 41 Cooper Square, down to its envelope-piercing tip. Woods presented this work in a lecture series that included Mayne, at the MAK-Austrian Museum of Applied Arts. His statements there are quoted in the 1991 book, Architecture in Transition: "When we confront strange, new, unfamiliar things, we are shocked, unsettled. Strangeness makes us come out of our familiar, comfortable ways of thinking and confront a new reality." Of his Free-Zone drawings he said, "At first, these bent and curved forms didn't seem to belong in the center of Berlin, but then I began to realize that yes, they did belong, as something unknown, undefined, uncertain, ambiguous, having to do with a potential in the city yet to be realized." Although Woods draws rather than builds, like Archigram, Mayne calls him a "very, very good architect." Woods has been a professor of architecture at Cooper Union for the last several years. While a closely shared sensibility can be credited, it's tempting to see more at work in 41 Cooper Square; a specific homage to Woods. What better gift could Mayne leave at Woods' doorstep than the chance to walk through one of his own visions?

A rendering from Lebbeus Woods' 1990 "Berlin Free-Zone 3-2" project closely prefigures Mayne's stair atrium at 41 Cooper Square, down to its envelope-piercing tip. Woods presented this work in a lecture series that included Mayne, at the MAK-Austrian Museum of Applied Arts. His statements there are quoted in the 1991 book, Architecture in Transition: "When we confront strange, new, unfamiliar things, we are shocked, unsettled. Strangeness makes us come out of our familiar, comfortable ways of thinking and confront a new reality." Of his Free-Zone drawings he said, "At first, these bent and curved forms didn't seem to belong in the center of Berlin, but then I began to realize that yes, they did belong, as something unknown, undefined, uncertain, ambiguous, having to do with a potential in the city yet to be realized." Although Woods draws rather than builds, like Archigram, Mayne calls him a "very, very good architect." Woods has been a professor of architecture at Cooper Union for the last several years. While a closely shared sensibility can be credited, it's tempting to see more at work in 41 Cooper Square; a specific homage to Woods. What better gift could Mayne leave at Woods' doorstep than the chance to walk through one of his own visions?

Ron Herron's Walking City idea produced some of Archigram's best known images. In his 1965 essay "A Clip-on Architecture," the architectural historian and theorist Reyner Banham argued that Archigram's appeal was that "it offers an image-starved world a new vision of the city of the future . . . Archigram is short on theory, long on draughtsmanship and craftsmanship. They're in the image business and they have been blessed with the power to create some of the most compelling images of our time . . . all done for the giggle. Like designing for pleasure, doing your own thing with the conviction that comes from the uninhibited exercise of creative talent braced by ruthless self-criticism. It's rare in any group - having the guts to do what you want, and the guts to say what you think - and because it's so rare it's beyond quibble. You accept Archigram at its own valuation or not at all, and there's been nothing much like that since Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies and Corb."

Ron Herron's Walking City idea produced some of Archigram's best known images. In his 1965 essay "A Clip-on Architecture," the architectural historian and theorist Reyner Banham argued that Archigram's appeal was that "it offers an image-starved world a new vision of the city of the future . . . Archigram is short on theory, long on draughtsmanship and craftsmanship. They're in the image business and they have been blessed with the power to create some of the most compelling images of our time . . . all done for the giggle. Like designing for pleasure, doing your own thing with the conviction that comes from the uninhibited exercise of creative talent braced by ruthless self-criticism. It's rare in any group - having the guts to do what you want, and the guts to say what you think - and because it's so rare it's beyond quibble. You accept Archigram at its own valuation or not at all, and there's been nothing much like that since Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies and Corb."

A 1994 Lebbeus Woods image evokes Archigram's Walking City in its vision of a "radical reconstruction" in Havana. As quoted in a New York Times profile by Nicolai Ouroussoff last year, Woods has said "I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world. All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces. But what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.” Woods commitment to real architecture underscores the importance of fantasy as an imaginative tool in architectural practice.

A 1994 Lebbeus Woods image evokes Archigram's Walking City in its vision of a "radical reconstruction" in Havana. As quoted in a New York Times profile by Nicolai Ouroussoff last year, Woods has said "I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world. All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces. But what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.” Woods commitment to real architecture underscores the importance of fantasy as an imaginative tool in architectural practice.

Visionary architecture crosses paths with science fiction: a set from Terry Gilliam's 1995 science fiction movie 12 Monkeys, left, appropriated an 1987 image by Lebbeus Woods, right. Woods successfully sued the filmmaker over its unauthorized use.

Visionary architecture crosses paths with science fiction: a set from Terry Gilliam's 1995 science fiction movie 12 Monkeys, left, appropriated an 1987 image by Lebbeus Woods, right. Woods successfully sued the filmmaker over its unauthorized use.

Woods voluntarily put his skill at fantasy to work for the movies as a "conceptual architect" on the movie Alien 3 in 1990. The movie changed directors and Woods' images weren't used.

Woods voluntarily put his skill at fantasy to work for the movies as a "conceptual architect" on the movie Alien 3 in 1990. The movie changed directors and Woods' images weren't used.

Special effects for science fiction movies like James Cameron's 1991 blockbuster, Terminator 2, courtesy of George Lucas's Industrial Light and Magic, have driven advances in graphic software ultimately used by architects. In this, architecture's expanded ability to explore and manufacture new forms can be said to be a direct result of science fiction movies. Cameron's forthcoming 3D movie, Avatar, will take special effects a step closer to merging with the real experience of space that is architecture's realm. A recent New Yorker article on Cameron and Avatar described reaction to a trailer for the film that was shown on Apple.com: "The message boards on Ain’t It Cool News, a fanboy site that started tracking 'Avatar' a decade ago, logged bitter disappointment. The fans there had anticipated 'eyeball rape.' One wrote, 'My eyeballs were merely fondled without permission.' ” A public appetite for visual spectacle may have jumped tracks from movies to the built environment.

Special effects for science fiction movies like James Cameron's 1991 blockbuster, Terminator 2, courtesy of George Lucas's Industrial Light and Magic, have driven advances in graphic software ultimately used by architects. In this, architecture's expanded ability to explore and manufacture new forms can be said to be a direct result of science fiction movies. Cameron's forthcoming 3D movie, Avatar, will take special effects a step closer to merging with the real experience of space that is architecture's realm. A recent New Yorker article on Cameron and Avatar described reaction to a trailer for the film that was shown on Apple.com: "The message boards on Ain’t It Cool News, a fanboy site that started tracking 'Avatar' a decade ago, logged bitter disappointment. The fans there had anticipated 'eyeball rape.' One wrote, 'My eyeballs were merely fondled without permission.' ” A public appetite for visual spectacle may have jumped tracks from movies to the built environment.

The cover of Rizzoli's fourth volume on Mayne's firm Morphosis features computer renderings of 41 Cooper Square's stair atrium. The built space was described as "a swoopy glass-fiber-reinforced-composite matrix that's like a 3D-modeling software mesh come to life" by Thomas Monchaux in The Architect's Newspaper. Advances in 3D computer technology have not only revolutionized what can be imagined, but the look of what gets built.

The cover of Rizzoli's fourth volume on Mayne's firm Morphosis features computer renderings of 41 Cooper Square's stair atrium. The built space was described as "a swoopy glass-fiber-reinforced-composite matrix that's like a 3D-modeling software mesh come to life" by Thomas Monchaux in The Architect's Newspaper. Advances in 3D computer technology have not only revolutionized what can be imagined, but the look of what gets built.

According to Architectural Record, Mayne “argues that his building is ‘highly contextual.’ The skin crimps and curves, he points out, to respond to the frenetic energy of its East Village environment.” Such statements help get designs built. It’s just as easy to see a willful strangeness. Rather than a bow to the sacred cow of contextualism, is 41 Cooper Square a rebuke to the repressive order of the architecture that surrounds it? Architecture that refuses to look like the known naturally enters the realm of the strange, the territory of fantasy and science fiction. From some angles, 41 Cooper Square resembles Archigram’s Walking City. Does it also offer “an image-starved world a new vision of the city of the future,” to use Reyner Banham’s explanation of Archigram’s appeal, or a bit of “eyeball rape” in the parlance of Ain’t It Cool News? The questions aren’t impertinent. Archigram’s legacy includes an embrace of popular culture, witnessed in both its comic book format and science fiction methods. High culture critics who disparaged such popular appeal, Banham said, had become “isolated from humanity by the humanities.”

According to Architectural Record, Mayne “argues that his building is ‘highly contextual.’ The skin crimps and curves, he points out, to respond to the frenetic energy of its East Village environment.” Such statements help get designs built. It’s just as easy to see a willful strangeness. Rather than a bow to the sacred cow of contextualism, is 41 Cooper Square a rebuke to the repressive order of the architecture that surrounds it? Architecture that refuses to look like the known naturally enters the realm of the strange, the territory of fantasy and science fiction. From some angles, 41 Cooper Square resembles Archigram’s Walking City. Does it also offer “an image-starved world a new vision of the city of the future,” to use Reyner Banham’s explanation of Archigram’s appeal, or a bit of “eyeball rape” in the parlance of Ain’t It Cool News? The questions aren’t impertinent. Archigram’s legacy includes an embrace of popular culture, witnessed in both its comic book format and science fiction methods. High culture critics who disparaged such popular appeal, Banham said, had become “isolated from humanity by the humanities.”

Fritz Lang's 1927 movie Metropolis took inspiration from New York's then-radical height, density and layered transportation to create a futuristic world. Thom Mayne cites Lang as an influence in his interview with Yoshio Futagawa, a case of architecture influencing science fiction and back again.

Fritz Lang's 1927 movie Metropolis took inspiration from New York's then-radical height, density and layered transportation to create a futuristic world. Thom Mayne cites Lang as an influence in his interview with Yoshio Futagawa, a case of architecture influencing science fiction and back again.

Ridley Scott's 1982 movie Blade Runner is often voted the best science fiction movie of all time in polls and surveys. It uses Frank Lloyd Wright's 1924 Ennis House to portray 2019 Los Angeles. Forward looking architecture and science fiction naturally share territory in the future.

Ridley Scott's 1982 movie Blade Runner is often voted the best science fiction movie of all time in polls and surveys. It uses Frank Lloyd Wright's 1924 Ennis House to portray 2019 Los Angeles. Forward looking architecture and science fiction naturally share territory in the future.

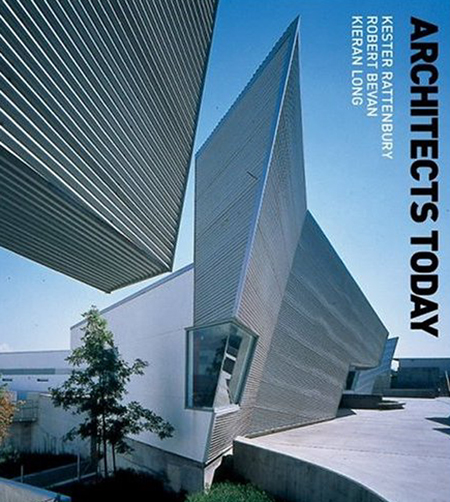

Thom Mayne's Diamond Ranch High Scool is featured on the cover of Architects Today, a 2004 book by Kester Rattenbury, Rob Bevan & Kieran Long. A rare example of contempoarary architectural writing that's neither unreadable nor condescending, the book has clear and insightful entries on over a hundred architects and firms, including Thom Mayne's Morphosis, Lebbeus Woods and Archigram. The entry on Archigram reads, "Contentious and troublesome, Archigram are extraordinarily influential. . . . Since the 1960s they have extended the language of architectural thought and expression, overturning its boundaries and conventions. Without building a single project (as a group, at least) they have arguably had more impact on architectural ideas than anyone since Le Corbusier. . . . This book is full of their pupils. . . . Archigram's non-building is an essential part of their influence. The ideas, uncompromised by the pragmatics of building, remain open to interpretation by the massive range of practices who have been influenced by them."

41 Cooper Square is not open to the public, although Cooper Union promises to begin tours soon, and post availability on its website.

Meanwhile, some relatively fine-grained observations by critics who've been inside are available online at Design Observer and the Architect's Newspaper.

Update: Lebbeus Woods has commented on this post in his own blog: http://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2011/01/06/41-cooper-square/

More on Lebbeus Woods: Mythical Lower Manhattan - In Memory of Lebbeus Woods

Thom Mayne's Diamond Ranch High Scool is featured on the cover of Architects Today, a 2004 book by Kester Rattenbury, Rob Bevan & Kieran Long. A rare example of contempoarary architectural writing that's neither unreadable nor condescending, the book has clear and insightful entries on over a hundred architects and firms, including Thom Mayne's Morphosis, Lebbeus Woods and Archigram. The entry on Archigram reads, "Contentious and troublesome, Archigram are extraordinarily influential. . . . Since the 1960s they have extended the language of architectural thought and expression, overturning its boundaries and conventions. Without building a single project (as a group, at least) they have arguably had more impact on architectural ideas than anyone since Le Corbusier. . . . This book is full of their pupils. . . . Archigram's non-building is an essential part of their influence. The ideas, uncompromised by the pragmatics of building, remain open to interpretation by the massive range of practices who have been influenced by them."

41 Cooper Square is not open to the public, although Cooper Union promises to begin tours soon, and post availability on its website.

Meanwhile, some relatively fine-grained observations by critics who've been inside are available online at Design Observer and the Architect's Newspaper.

Update: Lebbeus Woods has commented on this post in his own blog: http://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2011/01/06/41-cooper-square/

More on Lebbeus Woods: Mythical Lower Manhattan - In Memory of Lebbeus Woods

Subscribe Us

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a selection of cool articles every weeks