Atrocities

New plans still say "teardown" for Chelsea's oldest house

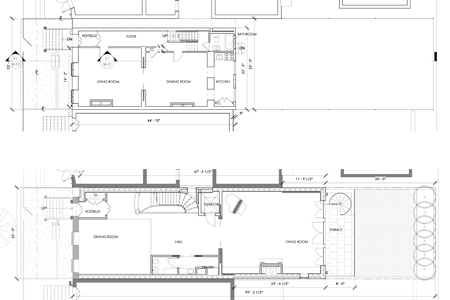

In an April 19 public hearing, the Landmarks Preservation Commission asked 404 West 20th Street's new owner Ajoy Kapoor to return with a more appropriate proposal for altering it. Just released, the revised proposal will go before a public meeting of the Commission on Tuesday. The new design takes a little off the top and still appears to require virtual demolition of all but the façade of the house, the oldest in the Chelsea Historic District. Excerpted from the updated presentation by Kapoor's architect William Suk and aligned for comparison are, left-to-right, the section of the existing house, the earlier proposal and the current proposal. The new building would still be well over twice the actual area of the approximately 4,000 square foot existing house, thanks in large part to a huge new basement excavation which would in itself make retention of the existing house difficult. In ArchiTakes' opinion, both the form and substance of the existing house are lost in its proposed replacement.

In an April 19 public hearing, the Landmarks Preservation Commission asked 404 West 20th Street's new owner Ajoy Kapoor to return with a more appropriate proposal for altering it. Just released, the revised proposal will go before a public meeting of the Commission on Tuesday. The new design takes a little off the top and still appears to require virtual demolition of all but the façade of the house, the oldest in the Chelsea Historic District. Excerpted from the updated presentation by Kapoor's architect William Suk and aligned for comparison are, left-to-right, the section of the existing house, the earlier proposal and the current proposal. The new building would still be well over twice the actual area of the approximately 4,000 square foot existing house, thanks in large part to a huge new basement excavation which would in itself make retention of the existing house difficult. In ArchiTakes' opinion, both the form and substance of the existing house are lost in its proposed replacement.

A plaque long mounted to the front of 404 West 20th Street is missing since the house was bought last year by Kapoor. The plaque is thought to have been installed shortly after the 1970 landmark designation of the Chelsea Historic District in which the house stands. The building's historic distinction and rare surviving wood frame complicate Kapoor’s plans, which depend heavily on Suk's assurances to the Commission that the house is structurally deficient. At the April 19th hearing and in Suk's presentation materials, these weren't backed up with an independent engineer's report, and his claims mainly pointed to the kind of construction technology and deformation normally found in old frame houses. His broad statement that "this whole house is falling apart" was not questioned by the commissioners. "I wouldn't put a kid to bed in that house," one commissioner said. "It's patently unsafe not to mention the building is clearly falling apart." Another commissioner didn't call the house a threat to children but dishearteningly seemed to take condemnation as a foregone conclusion and spoke of a possible solution that would "give some deference at least to that original structure and record some memory of it as best can be done." Why wouldn't the Landmarks Preservation Commission just preserve the landmark that's standing there? Many experts might say that in leaning only two inches to one side after 186 years it exhibits stability rather than the instability Suk makes of it. Shouldn't the spatial ambition of Kapoor's proposal inspire a little more scrutiny of his suggestions that preserving the existing house is a lost cause?

A plaque long mounted to the front of 404 West 20th Street is missing since the house was bought last year by Kapoor. The plaque is thought to have been installed shortly after the 1970 landmark designation of the Chelsea Historic District in which the house stands. The building's historic distinction and rare surviving wood frame complicate Kapoor’s plans, which depend heavily on Suk's assurances to the Commission that the house is structurally deficient. At the April 19th hearing and in Suk's presentation materials, these weren't backed up with an independent engineer's report, and his claims mainly pointed to the kind of construction technology and deformation normally found in old frame houses. His broad statement that "this whole house is falling apart" was not questioned by the commissioners. "I wouldn't put a kid to bed in that house," one commissioner said. "It's patently unsafe not to mention the building is clearly falling apart." Another commissioner didn't call the house a threat to children but dishearteningly seemed to take condemnation as a foregone conclusion and spoke of a possible solution that would "give some deference at least to that original structure and record some memory of it as best can be done." Why wouldn't the Landmarks Preservation Commission just preserve the landmark that's standing there? Many experts might say that in leaning only two inches to one side after 186 years it exhibits stability rather than the instability Suk makes of it. Shouldn't the spatial ambition of Kapoor's proposal inspire a little more scrutiny of his suggestions that preserving the existing house is a lost cause?

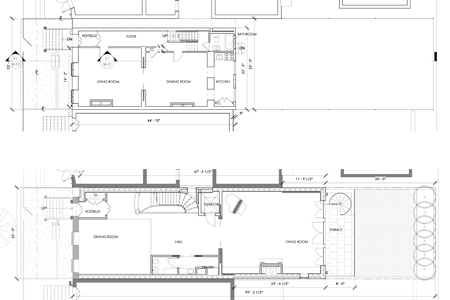

404's existing (top) and proposed (bottom) main floor plans from William Suk's latest presentation are aligned for comparison above. They continue to make obvious the disappearance of the old house save for its facade. The historic side alley seen just above the existing plan is subsumed in the much larger proposal, which also expands into the rear yard. Despite this apparent removal of the existing house, the project was described on the calendar of the Commission's website as an application "to construct additions and excavate the rear yard," and introduced as such in the public hearing. Although Community Board 4's advisory letter to the Commission and several public speakers in the public hearing criticized the house's proposed virtual replacement, Chair Srinavasan asked Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell, "How much of the building will be retained?” The Chair did not challenge Campbell's answer that, “in trying to stabilize the building and to bring it up to code, there is a significant amount of work that has to be done to the building.” Campbell otherwise spoke in the hearing of measures needed to ensure the house's "preservation" or "longevity." She is described on the website of her firm, Kramer Levin, as a former General Counsel of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

404's existing (top) and proposed (bottom) main floor plans from William Suk's latest presentation are aligned for comparison above. They continue to make obvious the disappearance of the old house save for its facade. The historic side alley seen just above the existing plan is subsumed in the much larger proposal, which also expands into the rear yard. Despite this apparent removal of the existing house, the project was described on the calendar of the Commission's website as an application "to construct additions and excavate the rear yard," and introduced as such in the public hearing. Although Community Board 4's advisory letter to the Commission and several public speakers in the public hearing criticized the house's proposed virtual replacement, Chair Srinavasan asked Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell, "How much of the building will be retained?” The Chair did not challenge Campbell's answer that, “in trying to stabilize the building and to bring it up to code, there is a significant amount of work that has to be done to the building.” Campbell otherwise spoke in the hearing of measures needed to ensure the house's "preservation" or "longevity." She is described on the website of her firm, Kramer Levin, as a former General Counsel of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

In a 1965 photo, 404's brick front is temporarily painted, while sunlight picks out its contrasting wood clapboard siding. A tiny alley exposes this evidence of the house’s frame construction, along with its historic pitched roof. A young Lesley Doyel stands in front. Her family bought the house that year after renting an apartment in it since 1952. Ms. Doyel is a longtime community activist and founder of the advocacy group, Save Chelsea. She and her husband Nick Fritsch sold the house to Ajoy Kapoor last year, having reason to be confident that its location in the Chelsea Historic District assured its preservation. According to the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission: "If your building is in a historic district, it's regulated the same way as an individual landmark."

In a 1965 photo, 404's brick front is temporarily painted, while sunlight picks out its contrasting wood clapboard siding. A tiny alley exposes this evidence of the house’s frame construction, along with its historic pitched roof. A young Lesley Doyel stands in front. Her family bought the house that year after renting an apartment in it since 1952. Ms. Doyel is a longtime community activist and founder of the advocacy group, Save Chelsea. She and her husband Nick Fritsch sold the house to Ajoy Kapoor last year, having reason to be confident that its location in the Chelsea Historic District assured its preservation. According to the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission: "If your building is in a historic district, it's regulated the same way as an individual landmark."

404's wood siding has been a staple of Chelsea walking tours for decades. "I remember being shown the side of that house in an architecture class way back in my NYU days," said Wendy Solem, a neighbor who called the house's possible fate "truly heartbreaking." Joyce Gold, who runs Joyce Gold History Tours of New York, said she has been leading groups to the house for 35 years and that it lets her "raise the subject of when wood could be used, and when it couldn’t." In response to major fires, construction of wood houses was progressively banned in zones extending northward as the city grew. By 1849 the ban reached 32nd Street. Surviving wood-frame houses such as this one are very rare in Manhattan, but this only scratches the surface of 404's significance to those who live in and visit the city and have an interest in exploring its roots.

404's wood siding has been a staple of Chelsea walking tours for decades. "I remember being shown the side of that house in an architecture class way back in my NYU days," said Wendy Solem, a neighbor who called the house's possible fate "truly heartbreaking." Joyce Gold, who runs Joyce Gold History Tours of New York, said she has been leading groups to the house for 35 years and that it lets her "raise the subject of when wood could be used, and when it couldn’t." In response to major fires, construction of wood houses was progressively banned in zones extending northward as the city grew. By 1849 the ban reached 32nd Street. Surviving wood-frame houses such as this one are very rare in Manhattan, but this only scratches the surface of 404's significance to those who live in and visit the city and have an interest in exploring its roots.

Images from the latest submission compare the existing alley (left) with its still-proposed infill (right), now with its recessed face in wood siding. The alley would be commemorated with a bizarre and inexplicable shallow clapboard niche imitative of the existing historic side wall. The historic side wall itself would be lost along with views of the house's period pitched roof. Current zoning doesn't allow creation of side yards less than eight feet wide, but pre-existing ones like 404's two-foot seven-inch alley are grandfathered. The alley can legally remain provided no addition to the house is built within eight feet of its side property line. Filling in the alley would eliminate this restriction on additions, while preserving it would still allow a substantial rear extension and preserve the visibility of the house's pitched roof seen through the alley, not to mention views of its historic wood siding. At one point in the public hearing, the Commission mistook the width of the building lot for twenty rather than twenty-five feet, and the width of the allowed addition zone -- if the alley were retained -- for twelve rather than seventeen feet. This appeared to generate sympathy for Kapoor's proposal to fill in the side yard. The Chair and commissioners were not corrected by William Suk, or Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell.

The Commission didn't voice recognition of the significance of the narrow alleyway itself. Chair Srinavasan dismissed it as a "quirk," saying "I can't get all romantic about that side yard" and stating that she could "support" filling it in. Yet romance has little to do with it. Research uncovers plenty of justification for preserving it as a once-pervasive but now unique feature of the Chelsea Historic District.

Images from the latest submission compare the existing alley (left) with its still-proposed infill (right), now with its recessed face in wood siding. The alley would be commemorated with a bizarre and inexplicable shallow clapboard niche imitative of the existing historic side wall. The historic side wall itself would be lost along with views of the house's period pitched roof. Current zoning doesn't allow creation of side yards less than eight feet wide, but pre-existing ones like 404's two-foot seven-inch alley are grandfathered. The alley can legally remain provided no addition to the house is built within eight feet of its side property line. Filling in the alley would eliminate this restriction on additions, while preserving it would still allow a substantial rear extension and preserve the visibility of the house's pitched roof seen through the alley, not to mention views of its historic wood siding. At one point in the public hearing, the Commission mistook the width of the building lot for twenty rather than twenty-five feet, and the width of the allowed addition zone -- if the alley were retained -- for twelve rather than seventeen feet. This appeared to generate sympathy for Kapoor's proposal to fill in the side yard. The Chair and commissioners were not corrected by William Suk, or Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell.

The Commission didn't voice recognition of the significance of the narrow alleyway itself. Chair Srinavasan dismissed it as a "quirk," saying "I can't get all romantic about that side yard" and stating that she could "support" filling it in. Yet romance has little to do with it. Research uncovers plenty of justification for preserving it as a once-pervasive but now unique feature of the Chelsea Historic District.

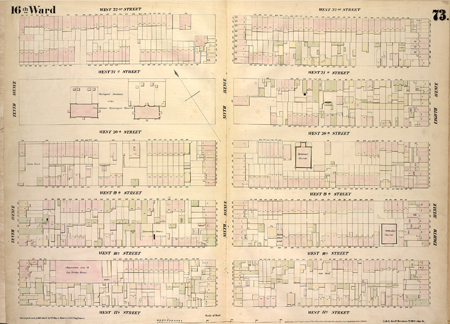

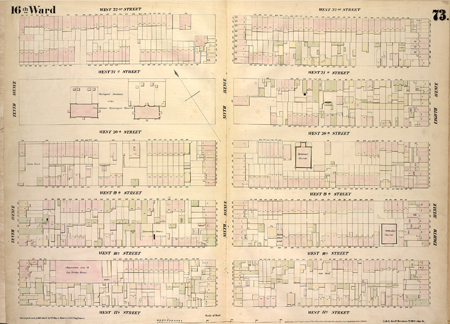

Wood-frame buildings are colored yellow, brick buildings pink and commercial ones green on Plate 73, featuring Chelsea, of the 1854 Perris Map of New York. This insurance atlas also used a system of dots and symbols to convey a structure's vulnerability and allow fire insurance companies to set rates without visiting buildings. 404 West 20th Street is seen just below the north arrow that's to the right of the original twin buildings of the largely-open General Theological Seminary block.

Wood-frame buildings are colored yellow, brick buildings pink and commercial ones green on Plate 73, featuring Chelsea, of the 1854 Perris Map of New York. This insurance atlas also used a system of dots and symbols to convey a structure's vulnerability and allow fire insurance companies to set rates without visiting buildings. 404 West 20th Street is seen just below the north arrow that's to the right of the original twin buildings of the largely-open General Theological Seminary block.

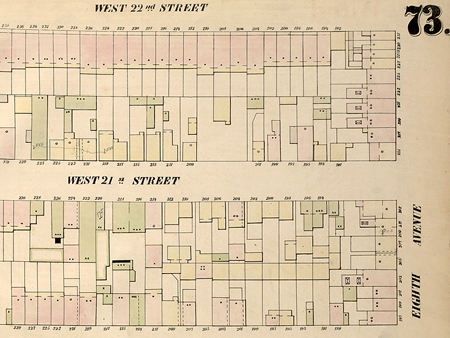

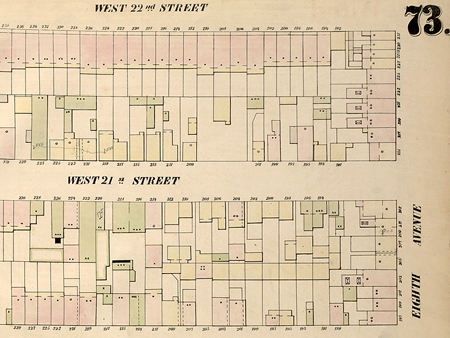

Plate 73 shows scores of yellow-coded frame houses in Chelsea with narrow side yards providing street access to back buildings. Many are visible in this detail of West 21st and 22nd Streets west of Eighth Avenue. These were often modest homes of self-employed tradesmen, which would in time give way to brick rowhouses filling the width of their lots. Sometimes the back buildings came first and were left accessible to the street by passages running next to or through later houses built at the street line. A few of the lots visible above still have only "back" buildings. The map is a snapshot of Chelsea in a moment of transition from village to city neighborhood. The prevalence of this arrangement was specific to Chelsea, as noted in Thomas Janvier's 1894 city history, In Old New York, which describes "conspicuous features of what once was Chelsea Village":

Plate 73 shows scores of yellow-coded frame houses in Chelsea with narrow side yards providing street access to back buildings. Many are visible in this detail of West 21st and 22nd Streets west of Eighth Avenue. These were often modest homes of self-employed tradesmen, which would in time give way to brick rowhouses filling the width of their lots. Sometimes the back buildings came first and were left accessible to the street by passages running next to or through later houses built at the street line. A few of the lots visible above still have only "back" buildings. The map is a snapshot of Chelsea in a moment of transition from village to city neighborhood. The prevalence of this arrangement was specific to Chelsea, as noted in Thomas Janvier's 1894 city history, In Old New York, which describes "conspicuous features of what once was Chelsea Village":

. . . even a few of the more modest remnants of that earlier period, the little wooden houses wherein dwelt folk of a humbler sort, still may be seen here and there: standing back shyly from the street in deep yards and having somewhat the abashed look of aged rustics confronted suddenly with city ways. But many more of these timber-toed veterans--true Chelsea pensioners--lie hidden away in the centres of the blocks, and may be found only by burrowing through alleyways beneath the outer line of prim brick houses of a modern time. Notably, on both sides of Twentieth Street, between the Seventh and Eighth avenues, these inner rows of houses may be found; and west of Eighth Avenue on the northern side of the way. But one may rest assured that wherever, in any of the blocks hereabouts, an alleyway opens there will be found an old wooden house or a whole row of old wooden houses."

404 West 20th Street's narrow alley is the sole survivor in the Chelsea Historic District, one of only four left in all of Chelsea, and the only one adjoining a wood frame house. Just two side alleys, each three feet wide, remain on the West 20th Street block Janvier highlighted. #207 (left) has been altered from its traditional rowhouse appearance. A sign on its alley gate reads "207R" for a rear building called a "walk-up apartment" in city records. A handful of Chelsea back buildings live on as residences. Diagonally across the street, #224 (right) recalls the look of 404 West 20th Street minus its distinctive clapboard side wall.

Just two side alleys, each three feet wide, remain on the West 20th Street block Janvier highlighted. #207 (left) has been altered from its traditional rowhouse appearance. A sign on its alley gate reads "207R" for a rear building called a "walk-up apartment" in city records. A handful of Chelsea back buildings live on as residences. Diagonally across the street, #224 (right) recalls the look of 404 West 20th Street minus its distinctive clapboard side wall.

On the same block, an example of Janvier's "whole row" of back buildings survives behind the Chelsea International Hostel, which occupies historic rowhouses #245 through #259. Their back yards form a long rear court opening to the street through a covered passage under #251. The low row of back buildings has been adapted as hostel units.

On the same block, an example of Janvier's "whole row" of back buildings survives behind the Chelsea International Hostel, which occupies historic rowhouses #245 through #259. Their back yards form a long rear court opening to the street through a covered passage under #251. The low row of back buildings has been adapted as hostel units.

248 West 22nd Street rounds out Chelsea's four surviving side alleys. The rowhouse's original entrance has been converted to a first floor window and its 3'-7" side yard to an open-air building entry and stair.

248 West 22nd Street rounds out Chelsea's four surviving side alleys. The rowhouse's original entrance has been converted to a first floor window and its 3'-7" side yard to an open-air building entry and stair.

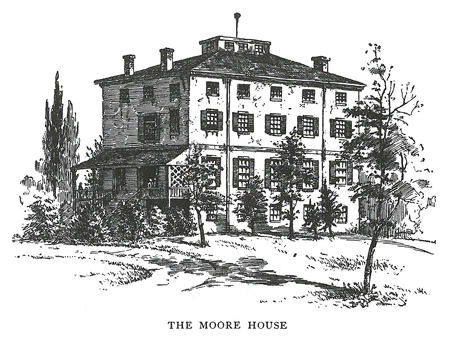

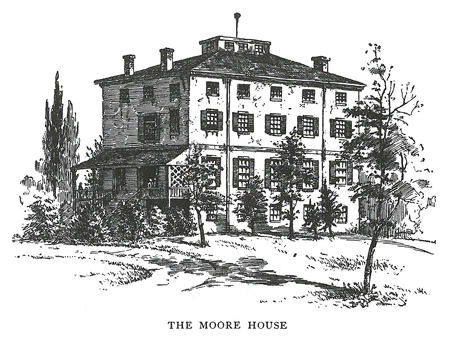

Janvier's description of antique back buildings as "timber-toed veterans--true Chelsea pensioners" is a sly reference to the wooden legs of military casualties and the man who gave the neighborhood its name, retired British Captain Thomas Clarke. A veteran of the French and Indian War, Clarke bought farmland in 1750 for an estate he wryly named after London's Royal Hospital Chelsea, which still operates as a retirement and nursing home for British soldiers known as Chelsea Pensioners. It was like calling his last home "the VA hospital." Clarke's estate house was located on what became the block south of today's London Terrace apartment complex. After it burned, his widow replaced it with the one pictured above in Janvier's book, which would become the home of his grandson, the ancient language professor, slave owner, real estate developer and " 'Twas the night before Christmas" poet, Clement Clarke Moore. When northward encroachment of the Manhattan street grid diced Moore's inherited property into city blocks, he subdivided them into building lots for sale.

Janvier's description of antique back buildings as "timber-toed veterans--true Chelsea pensioners" is a sly reference to the wooden legs of military casualties and the man who gave the neighborhood its name, retired British Captain Thomas Clarke. A veteran of the French and Indian War, Clarke bought farmland in 1750 for an estate he wryly named after London's Royal Hospital Chelsea, which still operates as a retirement and nursing home for British soldiers known as Chelsea Pensioners. It was like calling his last home "the VA hospital." Clarke's estate house was located on what became the block south of today's London Terrace apartment complex. After it burned, his widow replaced it with the one pictured above in Janvier's book, which would become the home of his grandson, the ancient language professor, slave owner, real estate developer and " 'Twas the night before Christmas" poet, Clement Clarke Moore. When northward encroachment of the Manhattan street grid diced Moore's inherited property into city blocks, he subdivided them into building lots for sale.

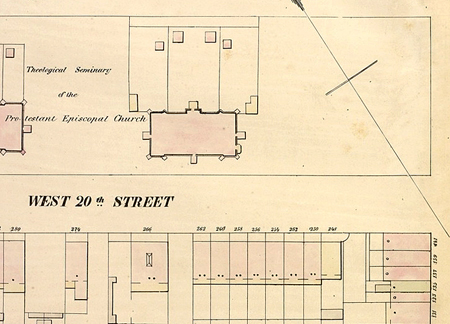

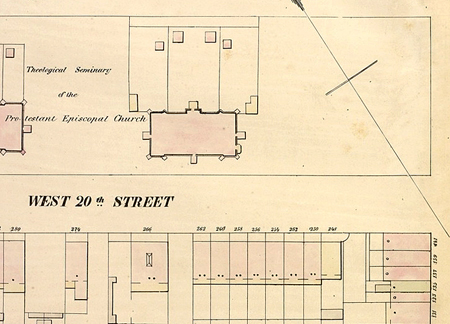

Moore donated a full block to the Episcopal Church for use as a seminary. Its campus would double as a town square, giving the community a focus and raising real estate values around it in the manner of contemporary neighborhood greens like Washington Square and Gramercy Park. The Seminary block's longtime name, "Chelsea Square," reflects this aim. The large building near the center of the map detail above is the Seminary's long-demolished 1827 East Building, one of America's first Gothic Revival buildings. Its twin, the 1836 West Building to its left, still stands, converted to luxury condos in Chelsea's post-High Line hyper-gentrification. The East and West Buildings fronted on West 20th Street, turning their impressive public faces south to exploit the play of sun and shadow. 404 West 20th Street -- the farthest-right house fronting on West 20th Street, colored yellow for its frame construction -- was built in 1829-30. Its front garden, side alley and a back building are visible. The map shows the front garden space Moore planned in front of the 20th Street lots to complement the leafy campus across the street. This zone ends in a quarter-circle just right of 404. Moore sold the lots west of 404 to the developer Don Alonzo Cushman, who in 1840 completed what is now considered one of the city's two best surviving rows of Greek Revival houses, matching the other one on Washington Square and validating Moore's town-square planning strategy. Cushman’s daughter would later build the Donac apartment building, named for him, on the other side of 404 across its alleyway.

Moore donated a full block to the Episcopal Church for use as a seminary. Its campus would double as a town square, giving the community a focus and raising real estate values around it in the manner of contemporary neighborhood greens like Washington Square and Gramercy Park. The Seminary block's longtime name, "Chelsea Square," reflects this aim. The large building near the center of the map detail above is the Seminary's long-demolished 1827 East Building, one of America's first Gothic Revival buildings. Its twin, the 1836 West Building to its left, still stands, converted to luxury condos in Chelsea's post-High Line hyper-gentrification. The East and West Buildings fronted on West 20th Street, turning their impressive public faces south to exploit the play of sun and shadow. 404 West 20th Street -- the farthest-right house fronting on West 20th Street, colored yellow for its frame construction -- was built in 1829-30. Its front garden, side alley and a back building are visible. The map shows the front garden space Moore planned in front of the 20th Street lots to complement the leafy campus across the street. This zone ends in a quarter-circle just right of 404. Moore sold the lots west of 404 to the developer Don Alonzo Cushman, who in 1840 completed what is now considered one of the city's two best surviving rows of Greek Revival houses, matching the other one on Washington Square and validating Moore's town-square planning strategy. Cushman’s daughter would later build the Donac apartment building, named for him, on the other side of 404 across its alleyway.

404's meeting of clapboard and brick shows the direct involvement of Clement Clarke Moore. According to the Landmarks Commission's 1970 Chelsea Historic District Designation Report:

404's meeting of clapboard and brick shows the direct involvement of Clement Clarke Moore. According to the Landmarks Commission's 1970 Chelsea Historic District Designation Report:

No. 404, the oldest house in the Chelsea Historic District, was built in 1829-30 for Hugh Walker on land leased from Clement Clarke Moore for forty dollars per year. The lease stated that if, during the first seven years, a good and substantial house was erected, being two stories or more, constructed of brick or stone, or having a brick or stone front, the lessor would pay the full value of the house at the end of the lease. . . . The original clapboard of one sidewall is still visible on the east side of the house.

Moore might have settled for less than an all-brick or stone building in resignation to the lot's still-open surroundings at the northern city outskirts, land appealing to "folk of a humbler sort," to get the ball rolling on Chelsea's development. In stipulating a brick or stone face, this starter house would at least contribute to the dignity and property value he hoped to see at the centerpiece block of his new community. It's unclear whether his tenant Hugh Walker lived in or used a back building before building the brick-faced house for which Moore reimbursed him, on the model Janvier describes. 404's brick face may indeed have helped convince Cushman to develop his impressive row next door a few years later. The more humble character displayed behind its brick face makes it the indispensable first page of Chelsea’s domestic history. The Donac was completed in 1898 to the design of the mansion architect C.P.H. Gilbert. Its form respects the quarter-circle setback Clement Clarke Moore conceived to ease into the adjoining front garden setback. The lowered bay within the Donac's curve creates the impression that the building is stepping down to the height of its humble neighbor in the same graceful gesture. This masterstroke of suggestion is greatly helped by the alley’s cushion of breathing space between them. Kapoor's proposed alley infill would bring 404 into formal collision with the Donac.

The Donac was completed in 1898 to the design of the mansion architect C.P.H. Gilbert. Its form respects the quarter-circle setback Clement Clarke Moore conceived to ease into the adjoining front garden setback. The lowered bay within the Donac's curve creates the impression that the building is stepping down to the height of its humble neighbor in the same graceful gesture. This masterstroke of suggestion is greatly helped by the alley’s cushion of breathing space between them. Kapoor's proposed alley infill would bring 404 into formal collision with the Donac.

Moore later took on a property manager, James N. Wells, the carpenter who built St. Luke's Church in Greenwich Village. Wells moved into the brick house at Ninth Avenue and 21st Street (above) when it was newly-built in 1833. According to a New York Times article by Christopher Gray, Wells

Moore later took on a property manager, James N. Wells, the carpenter who built St. Luke's Church in Greenwich Village. Wells moved into the brick house at Ninth Avenue and 21st Street (above) when it was newly-built in 1833. According to a New York Times article by Christopher Gray, Wells

. . . developed the rather sophisticated restrictions that Moore imposed on his lots when private house construction began in earnest in the mid-1830's. These covenants not only included prohibitions against stables and rear buildings, but also required tree planting. Clearly Moore and Wells were taking pains to create a first-class residential district.

Chelsea's early frame houses, alleys and back buildings would indeed fade away as the village became Moore's intended city neighborhood of genteel brick rowhouses, before they were subdivided into apartments for waterfront workers, before they declined in the era of urban flight, before they were rediscovered largely by gay pioneers, before the influx of a few hundred galleries, and before the High Line made it the real-estate jackpot now threatening the layered history and resonance that make it uniquely and richly Chelsea. Update: In a July 26, 2016, public meeting, the Landmarks Preservation Commission approved a revised proposal which will still replace 404 West 20th Street with a much larger house, fill in its side yard and preserve only its street façade. Commissioner Michael Devonshire alone spoke and voted against the proposal, for "obliterating" the historic house. More posts on this block of Chelsea: Buying Michael Bolla's Chelsea Mansion for Dummies Losing Ground at Chelsea Square The Seminary Block of West 20th StreetNew plans still say "teardown" for Chelsea's oldest house

In an April 19 public hearing, the Landmarks Preservation Commission asked 404 West 20th Street's new owner Ajoy Kapoor to return with a more appropriate proposal for altering it. Just released, the revised proposal will go before a public meeting of the Commission on Tuesday. The new design takes a little off the top and still appears to require virtual demolition of all but the façade of the house, the oldest in the Chelsea Historic District. Excerpted from the updated presentation by Kapoor's architect William Suk and aligned for comparison are, left-to-right, the section of the existing house, the earlier proposal and the current proposal. The new building would still be well over twice the actual area of the approximately 4,000 square foot existing house, thanks in large part to a huge new basement excavation which would in itself make retention of the existing house difficult. In ArchiTakes' opinion, both the form and substance of the existing house are lost in its proposed replacement.

In an April 19 public hearing, the Landmarks Preservation Commission asked 404 West 20th Street's new owner Ajoy Kapoor to return with a more appropriate proposal for altering it. Just released, the revised proposal will go before a public meeting of the Commission on Tuesday. The new design takes a little off the top and still appears to require virtual demolition of all but the façade of the house, the oldest in the Chelsea Historic District. Excerpted from the updated presentation by Kapoor's architect William Suk and aligned for comparison are, left-to-right, the section of the existing house, the earlier proposal and the current proposal. The new building would still be well over twice the actual area of the approximately 4,000 square foot existing house, thanks in large part to a huge new basement excavation which would in itself make retention of the existing house difficult. In ArchiTakes' opinion, both the form and substance of the existing house are lost in its proposed replacement.

A plaque long mounted to the front of 404 West 20th Street is missing since the house was bought last year by Kapoor. The plaque is thought to have been installed shortly after the 1970 landmark designation of the Chelsea Historic District in which the house stands. The building's historic distinction and rare surviving wood frame complicate Kapoor’s plans, which depend heavily on Suk's assurances to the Commission that the house is structurally deficient. At the April 19th hearing and in Suk's presentation materials, these weren't backed up with an independent engineer's report, and his claims mainly pointed to the kind of construction technology and deformation normally found in old frame houses. His broad statement that "this whole house is falling apart" was not questioned by the commissioners. "I wouldn't put a kid to bed in that house," one commissioner said. "It's patently unsafe not to mention the building is clearly falling apart." Another commissioner didn't call the house a threat to children but dishearteningly seemed to take condemnation as a foregone conclusion and spoke of a possible solution that would "give some deference at least to that original structure and record some memory of it as best can be done." Why wouldn't the Landmarks Preservation Commission just preserve the landmark that's standing there? Many experts might say that in leaning only two inches to one side after 186 years it exhibits stability rather than the instability Suk makes of it. Shouldn't the spatial ambition of Kapoor's proposal inspire a little more scrutiny of his suggestions that preserving the existing house is a lost cause?

A plaque long mounted to the front of 404 West 20th Street is missing since the house was bought last year by Kapoor. The plaque is thought to have been installed shortly after the 1970 landmark designation of the Chelsea Historic District in which the house stands. The building's historic distinction and rare surviving wood frame complicate Kapoor’s plans, which depend heavily on Suk's assurances to the Commission that the house is structurally deficient. At the April 19th hearing and in Suk's presentation materials, these weren't backed up with an independent engineer's report, and his claims mainly pointed to the kind of construction technology and deformation normally found in old frame houses. His broad statement that "this whole house is falling apart" was not questioned by the commissioners. "I wouldn't put a kid to bed in that house," one commissioner said. "It's patently unsafe not to mention the building is clearly falling apart." Another commissioner didn't call the house a threat to children but dishearteningly seemed to take condemnation as a foregone conclusion and spoke of a possible solution that would "give some deference at least to that original structure and record some memory of it as best can be done." Why wouldn't the Landmarks Preservation Commission just preserve the landmark that's standing there? Many experts might say that in leaning only two inches to one side after 186 years it exhibits stability rather than the instability Suk makes of it. Shouldn't the spatial ambition of Kapoor's proposal inspire a little more scrutiny of his suggestions that preserving the existing house is a lost cause?

404's existing (top) and proposed (bottom) main floor plans from William Suk's latest presentation are aligned for comparison above. They continue to make obvious the disappearance of the old house save for its facade. The historic side alley seen just above the existing plan is subsumed in the much larger proposal, which also expands into the rear yard. Despite this apparent removal of the existing house, the project was described on the calendar of the Commission's website as an application "to construct additions and excavate the rear yard," and introduced as such in the public hearing. Although Community Board 4's advisory letter to the Commission and several public speakers in the public hearing criticized the house's proposed virtual replacement, Chair Srinavasan asked Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell, "How much of the building will be retained?” The Chair did not challenge Campbell's answer that, “in trying to stabilize the building and to bring it up to code, there is a significant amount of work that has to be done to the building.” Campbell otherwise spoke in the hearing of measures needed to ensure the house's "preservation" or "longevity." She is described on the website of her firm, Kramer Levin, as a former General Counsel of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

404's existing (top) and proposed (bottom) main floor plans from William Suk's latest presentation are aligned for comparison above. They continue to make obvious the disappearance of the old house save for its facade. The historic side alley seen just above the existing plan is subsumed in the much larger proposal, which also expands into the rear yard. Despite this apparent removal of the existing house, the project was described on the calendar of the Commission's website as an application "to construct additions and excavate the rear yard," and introduced as such in the public hearing. Although Community Board 4's advisory letter to the Commission and several public speakers in the public hearing criticized the house's proposed virtual replacement, Chair Srinavasan asked Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell, "How much of the building will be retained?” The Chair did not challenge Campbell's answer that, “in trying to stabilize the building and to bring it up to code, there is a significant amount of work that has to be done to the building.” Campbell otherwise spoke in the hearing of measures needed to ensure the house's "preservation" or "longevity." She is described on the website of her firm, Kramer Levin, as a former General Counsel of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

In a 1965 photo, 404's brick front is temporarily painted, while sunlight picks out its contrasting wood clapboard siding. A tiny alley exposes this evidence of the house’s frame construction, along with its historic pitched roof. A young Lesley Doyel stands in front. Her family bought the house that year after renting an apartment in it since 1952. Ms. Doyel is a longtime community activist and founder of the advocacy group, Save Chelsea. She and her husband Nick Fritsch sold the house to Ajoy Kapoor last year, having reason to be confident that its location in the Chelsea Historic District assured its preservation. According to the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission: "If your building is in a historic district, it's regulated the same way as an individual landmark."

In a 1965 photo, 404's brick front is temporarily painted, while sunlight picks out its contrasting wood clapboard siding. A tiny alley exposes this evidence of the house’s frame construction, along with its historic pitched roof. A young Lesley Doyel stands in front. Her family bought the house that year after renting an apartment in it since 1952. Ms. Doyel is a longtime community activist and founder of the advocacy group, Save Chelsea. She and her husband Nick Fritsch sold the house to Ajoy Kapoor last year, having reason to be confident that its location in the Chelsea Historic District assured its preservation. According to the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission: "If your building is in a historic district, it's regulated the same way as an individual landmark."

404's wood siding has been a staple of Chelsea walking tours for decades. "I remember being shown the side of that house in an architecture class way back in my NYU days," said Wendy Solem, a neighbor who called the house's possible fate "truly heartbreaking." Joyce Gold, who runs Joyce Gold History Tours of New York, said she has been leading groups to the house for 35 years and that it lets her "raise the subject of when wood could be used, and when it couldn’t." In response to major fires, construction of wood houses was progressively banned in zones extending northward as the city grew. By 1849 the ban reached 32nd Street. Surviving wood-frame houses such as this one are very rare in Manhattan, but this only scratches the surface of 404's significance to those who live in and visit the city and have an interest in exploring its roots.

404's wood siding has been a staple of Chelsea walking tours for decades. "I remember being shown the side of that house in an architecture class way back in my NYU days," said Wendy Solem, a neighbor who called the house's possible fate "truly heartbreaking." Joyce Gold, who runs Joyce Gold History Tours of New York, said she has been leading groups to the house for 35 years and that it lets her "raise the subject of when wood could be used, and when it couldn’t." In response to major fires, construction of wood houses was progressively banned in zones extending northward as the city grew. By 1849 the ban reached 32nd Street. Surviving wood-frame houses such as this one are very rare in Manhattan, but this only scratches the surface of 404's significance to those who live in and visit the city and have an interest in exploring its roots.

Images from the latest submission compare the existing alley (left) with its still-proposed infill (right), now with its recessed face in wood siding. The alley would be commemorated with a bizarre and inexplicable shallow clapboard niche imitative of the existing historic side wall. The historic side wall itself would be lost along with views of the house's period pitched roof. Current zoning doesn't allow creation of side yards less than eight feet wide, but pre-existing ones like 404's two-foot seven-inch alley are grandfathered. The alley can legally remain provided no addition to the house is built within eight feet of its side property line. Filling in the alley would eliminate this restriction on additions, while preserving it would still allow a substantial rear extension and preserve the visibility of the house's pitched roof seen through the alley, not to mention views of its historic wood siding. At one point in the public hearing, the Commission mistook the width of the building lot for twenty rather than twenty-five feet, and the width of the allowed addition zone -- if the alley were retained -- for twelve rather than seventeen feet. This appeared to generate sympathy for Kapoor's proposal to fill in the side yard. The Chair and commissioners were not corrected by William Suk, or Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell.

The Commission didn't voice recognition of the significance of the narrow alleyway itself. Chair Srinavasan dismissed it as a "quirk," saying "I can't get all romantic about that side yard" and stating that she could "support" filling it in. Yet romance has little to do with it. Research uncovers plenty of justification for preserving it as a once-pervasive but now unique feature of the Chelsea Historic District.

Images from the latest submission compare the existing alley (left) with its still-proposed infill (right), now with its recessed face in wood siding. The alley would be commemorated with a bizarre and inexplicable shallow clapboard niche imitative of the existing historic side wall. The historic side wall itself would be lost along with views of the house's period pitched roof. Current zoning doesn't allow creation of side yards less than eight feet wide, but pre-existing ones like 404's two-foot seven-inch alley are grandfathered. The alley can legally remain provided no addition to the house is built within eight feet of its side property line. Filling in the alley would eliminate this restriction on additions, while preserving it would still allow a substantial rear extension and preserve the visibility of the house's pitched roof seen through the alley, not to mention views of its historic wood siding. At one point in the public hearing, the Commission mistook the width of the building lot for twenty rather than twenty-five feet, and the width of the allowed addition zone -- if the alley were retained -- for twelve rather than seventeen feet. This appeared to generate sympathy for Kapoor's proposal to fill in the side yard. The Chair and commissioners were not corrected by William Suk, or Kapoor's counsel, Valerie Campbell.

The Commission didn't voice recognition of the significance of the narrow alleyway itself. Chair Srinavasan dismissed it as a "quirk," saying "I can't get all romantic about that side yard" and stating that she could "support" filling it in. Yet romance has little to do with it. Research uncovers plenty of justification for preserving it as a once-pervasive but now unique feature of the Chelsea Historic District.

Wood-frame buildings are colored yellow, brick buildings pink and commercial ones green on Plate 73, featuring Chelsea, of the 1854 Perris Map of New York. This insurance atlas also used a system of dots and symbols to convey a structure's vulnerability and allow fire insurance companies to set rates without visiting buildings. 404 West 20th Street is seen just below the north arrow that's to the right of the original twin buildings of the largely-open General Theological Seminary block.

Wood-frame buildings are colored yellow, brick buildings pink and commercial ones green on Plate 73, featuring Chelsea, of the 1854 Perris Map of New York. This insurance atlas also used a system of dots and symbols to convey a structure's vulnerability and allow fire insurance companies to set rates without visiting buildings. 404 West 20th Street is seen just below the north arrow that's to the right of the original twin buildings of the largely-open General Theological Seminary block.

Plate 73 shows scores of yellow-coded frame houses in Chelsea with narrow side yards providing street access to back buildings. Many are visible in this detail of West 21st and 22nd Streets west of Eighth Avenue. These were often modest homes of self-employed tradesmen, which would in time give way to brick rowhouses filling the width of their lots. Sometimes the back buildings came first and were left accessible to the street by passages running next to or through later houses built at the street line. A few of the lots visible above still have only "back" buildings. The map is a snapshot of Chelsea in a moment of transition from village to city neighborhood. The prevalence of this arrangement was specific to Chelsea, as noted in Thomas Janvier's 1894 city history, In Old New York, which describes "conspicuous features of what once was Chelsea Village":

Plate 73 shows scores of yellow-coded frame houses in Chelsea with narrow side yards providing street access to back buildings. Many are visible in this detail of West 21st and 22nd Streets west of Eighth Avenue. These were often modest homes of self-employed tradesmen, which would in time give way to brick rowhouses filling the width of their lots. Sometimes the back buildings came first and were left accessible to the street by passages running next to or through later houses built at the street line. A few of the lots visible above still have only "back" buildings. The map is a snapshot of Chelsea in a moment of transition from village to city neighborhood. The prevalence of this arrangement was specific to Chelsea, as noted in Thomas Janvier's 1894 city history, In Old New York, which describes "conspicuous features of what once was Chelsea Village":

. . . even a few of the more modest remnants of that earlier period, the little wooden houses wherein dwelt folk of a humbler sort, still may be seen here and there: standing back shyly from the street in deep yards and having somewhat the abashed look of aged rustics confronted suddenly with city ways. But many more of these timber-toed veterans--true Chelsea pensioners--lie hidden away in the centres of the blocks, and may be found only by burrowing through alleyways beneath the outer line of prim brick houses of a modern time. Notably, on both sides of Twentieth Street, between the Seventh and Eighth avenues, these inner rows of houses may be found; and west of Eighth Avenue on the northern side of the way. But one may rest assured that wherever, in any of the blocks hereabouts, an alleyway opens there will be found an old wooden house or a whole row of old wooden houses."

404 West 20th Street's narrow alley is the sole survivor in the Chelsea Historic District, one of only four left in all of Chelsea, and the only one adjoining a wood frame house. Just two side alleys, each three feet wide, remain on the West 20th Street block Janvier highlighted. #207 (left) has been altered from its traditional rowhouse appearance. A sign on its alley gate reads "207R" for a rear building called a "walk-up apartment" in city records. A handful of Chelsea back buildings live on as residences. Diagonally across the street, #224 (right) recalls the look of 404 West 20th Street minus its distinctive clapboard side wall.

Just two side alleys, each three feet wide, remain on the West 20th Street block Janvier highlighted. #207 (left) has been altered from its traditional rowhouse appearance. A sign on its alley gate reads "207R" for a rear building called a "walk-up apartment" in city records. A handful of Chelsea back buildings live on as residences. Diagonally across the street, #224 (right) recalls the look of 404 West 20th Street minus its distinctive clapboard side wall.

On the same block, an example of Janvier's "whole row" of back buildings survives behind the Chelsea International Hostel, which occupies historic rowhouses #245 through #259. Their back yards form a long rear court opening to the street through a covered passage under #251. The low row of back buildings has been adapted as hostel units.

On the same block, an example of Janvier's "whole row" of back buildings survives behind the Chelsea International Hostel, which occupies historic rowhouses #245 through #259. Their back yards form a long rear court opening to the street through a covered passage under #251. The low row of back buildings has been adapted as hostel units.

248 West 22nd Street rounds out Chelsea's four surviving side alleys. The rowhouse's original entrance has been converted to a first floor window and its 3'-7" side yard to an open-air building entry and stair.

248 West 22nd Street rounds out Chelsea's four surviving side alleys. The rowhouse's original entrance has been converted to a first floor window and its 3'-7" side yard to an open-air building entry and stair.

Janvier's description of antique back buildings as "timber-toed veterans--true Chelsea pensioners" is a sly reference to the wooden legs of military casualties and the man who gave the neighborhood its name, retired British Captain Thomas Clarke. A veteran of the French and Indian War, Clarke bought farmland in 1750 for an estate he wryly named after London's Royal Hospital Chelsea, which still operates as a retirement and nursing home for British soldiers known as Chelsea Pensioners. It was like calling his last home "the VA hospital." Clarke's estate house was located on what became the block south of today's London Terrace apartment complex. After it burned, his widow replaced it with the one pictured above in Janvier's book, which would become the home of his grandson, the ancient language professor, slave owner, real estate developer and " 'Twas the night before Christmas" poet, Clement Clarke Moore. When northward encroachment of the Manhattan street grid diced Moore's inherited property into city blocks, he subdivided them into building lots for sale.

Janvier's description of antique back buildings as "timber-toed veterans--true Chelsea pensioners" is a sly reference to the wooden legs of military casualties and the man who gave the neighborhood its name, retired British Captain Thomas Clarke. A veteran of the French and Indian War, Clarke bought farmland in 1750 for an estate he wryly named after London's Royal Hospital Chelsea, which still operates as a retirement and nursing home for British soldiers known as Chelsea Pensioners. It was like calling his last home "the VA hospital." Clarke's estate house was located on what became the block south of today's London Terrace apartment complex. After it burned, his widow replaced it with the one pictured above in Janvier's book, which would become the home of his grandson, the ancient language professor, slave owner, real estate developer and " 'Twas the night before Christmas" poet, Clement Clarke Moore. When northward encroachment of the Manhattan street grid diced Moore's inherited property into city blocks, he subdivided them into building lots for sale.

Moore donated a full block to the Episcopal Church for use as a seminary. Its campus would double as a town square, giving the community a focus and raising real estate values around it in the manner of contemporary neighborhood greens like Washington Square and Gramercy Park. The Seminary block's longtime name, "Chelsea Square," reflects this aim. The large building near the center of the map detail above is the Seminary's long-demolished 1827 East Building, one of America's first Gothic Revival buildings. Its twin, the 1836 West Building to its left, still stands, converted to luxury condos in Chelsea's post-High Line hyper-gentrification. The East and West Buildings fronted on West 20th Street, turning their impressive public faces south to exploit the play of sun and shadow. 404 West 20th Street -- the farthest-right house fronting on West 20th Street, colored yellow for its frame construction -- was built in 1829-30. Its front garden, side alley and a back building are visible. The map shows the front garden space Moore planned in front of the 20th Street lots to complement the leafy campus across the street. This zone ends in a quarter-circle just right of 404. Moore sold the lots west of 404 to the developer Don Alonzo Cushman, who in 1840 completed what is now considered one of the city's two best surviving rows of Greek Revival houses, matching the other one on Washington Square and validating Moore's town-square planning strategy. Cushman’s daughter would later build the Donac apartment building, named for him, on the other side of 404 across its alleyway.

Moore donated a full block to the Episcopal Church for use as a seminary. Its campus would double as a town square, giving the community a focus and raising real estate values around it in the manner of contemporary neighborhood greens like Washington Square and Gramercy Park. The Seminary block's longtime name, "Chelsea Square," reflects this aim. The large building near the center of the map detail above is the Seminary's long-demolished 1827 East Building, one of America's first Gothic Revival buildings. Its twin, the 1836 West Building to its left, still stands, converted to luxury condos in Chelsea's post-High Line hyper-gentrification. The East and West Buildings fronted on West 20th Street, turning their impressive public faces south to exploit the play of sun and shadow. 404 West 20th Street -- the farthest-right house fronting on West 20th Street, colored yellow for its frame construction -- was built in 1829-30. Its front garden, side alley and a back building are visible. The map shows the front garden space Moore planned in front of the 20th Street lots to complement the leafy campus across the street. This zone ends in a quarter-circle just right of 404. Moore sold the lots west of 404 to the developer Don Alonzo Cushman, who in 1840 completed what is now considered one of the city's two best surviving rows of Greek Revival houses, matching the other one on Washington Square and validating Moore's town-square planning strategy. Cushman’s daughter would later build the Donac apartment building, named for him, on the other side of 404 across its alleyway.

404's meeting of clapboard and brick shows the direct involvement of Clement Clarke Moore. According to the Landmarks Commission's 1970 Chelsea Historic District Designation Report:

404's meeting of clapboard and brick shows the direct involvement of Clement Clarke Moore. According to the Landmarks Commission's 1970 Chelsea Historic District Designation Report:

No. 404, the oldest house in the Chelsea Historic District, was built in 1829-30 for Hugh Walker on land leased from Clement Clarke Moore for forty dollars per year. The lease stated that if, during the first seven years, a good and substantial house was erected, being two stories or more, constructed of brick or stone, or having a brick or stone front, the lessor would pay the full value of the house at the end of the lease. . . . The original clapboard of one sidewall is still visible on the east side of the house.

Moore might have settled for less than an all-brick or stone building in resignation to the lot's still-open surroundings at the northern city outskirts, land appealing to "folk of a humbler sort," to get the ball rolling on Chelsea's development. In stipulating a brick or stone face, this starter house would at least contribute to the dignity and property value he hoped to see at the centerpiece block of his new community. It's unclear whether his tenant Hugh Walker lived in or used a back building before building the brick-faced house for which Moore reimbursed him, on the model Janvier describes. 404's brick face may indeed have helped convince Cushman to develop his impressive row next door a few years later. The more humble character displayed behind its brick face makes it the indispensable first page of Chelsea’s domestic history. The Donac was completed in 1898 to the design of the mansion architect C.P.H. Gilbert. Its form respects the quarter-circle setback Clement Clarke Moore conceived to ease into the adjoining front garden setback. The lowered bay within the Donac's curve creates the impression that the building is stepping down to the height of its humble neighbor in the same graceful gesture. This masterstroke of suggestion is greatly helped by the alley’s cushion of breathing space between them. Kapoor's proposed alley infill would bring 404 into formal collision with the Donac.

The Donac was completed in 1898 to the design of the mansion architect C.P.H. Gilbert. Its form respects the quarter-circle setback Clement Clarke Moore conceived to ease into the adjoining front garden setback. The lowered bay within the Donac's curve creates the impression that the building is stepping down to the height of its humble neighbor in the same graceful gesture. This masterstroke of suggestion is greatly helped by the alley’s cushion of breathing space between them. Kapoor's proposed alley infill would bring 404 into formal collision with the Donac.

Moore later took on a property manager, James N. Wells, the carpenter who built St. Luke's Church in Greenwich Village. Wells moved into the brick house at Ninth Avenue and 21st Street (above) when it was newly-built in 1833. According to a New York Times article by Christopher Gray, Wells

Moore later took on a property manager, James N. Wells, the carpenter who built St. Luke's Church in Greenwich Village. Wells moved into the brick house at Ninth Avenue and 21st Street (above) when it was newly-built in 1833. According to a New York Times article by Christopher Gray, Wells

. . . developed the rather sophisticated restrictions that Moore imposed on his lots when private house construction began in earnest in the mid-1830's. These covenants not only included prohibitions against stables and rear buildings, but also required tree planting. Clearly Moore and Wells were taking pains to create a first-class residential district.

Chelsea's early frame houses, alleys and back buildings would indeed fade away as the village became Moore's intended city neighborhood of genteel brick rowhouses, before they were subdivided into apartments for waterfront workers, before they declined in the era of urban flight, before they were rediscovered largely by gay pioneers, before the influx of a few hundred galleries, and before the High Line made it the real-estate jackpot now threatening the layered history and resonance that make it uniquely and richly Chelsea. Update: In a July 26, 2016, public meeting, the Landmarks Preservation Commission approved a revised proposal which will still replace 404 West 20th Street with a much larger house, fill in its side yard and preserve only its street façade. Commissioner Michael Devonshire alone spoke and voted against the proposal, for "obliterating" the historic house. More posts on this block of Chelsea: Buying Michael Bolla's Chelsea Mansion for Dummies Losing Ground at Chelsea Square The Seminary Block of West 20th StreetThe Chelsea Market Deal, brought to you by ULURP

From right to left, Amanda Burden, Christine Quinn, Mayor Bloomberg and Boss Tweed reprise Thomas Nast's ring of passed blame around Chelsea Market in a flyer that's started appearing on Chelsea streets.

On October 19th, I and others met with City Council Speaker Christine Quinn to discuss Jamestown Properties’ proposed rezoning of Chelsea Market, aimed at adding over a quarter-million square feet of office space to the historic complex. I twice asked Speaker Quinn just how she saw the proposal making sense on zoning basics of use, bulk or environmental impact. She would only say that she hadn’t completed her review, but then still had no answer when we met six days later, just before the City Council's land-use committee voted to support the proposal, surely with Quinn's endorsement. Only Speaker Quinn could have stopped the project, but she advanced it in the face of overwhelming community resistance and without being able to say how it was good zoning.

If Speaker Quinn is already beholden to real estate interests in her expected run for mayor next year, she promises to bring to that office a fourth term of the Bloomberg administration’s worst feature; a pro-development, anti-oversight bias. In this New York, real estate runs politics and deals trump zoning. In a New York Times article on the Council's Chelsea Market vote, David Chen wrote that in remaining “conspicuously quiet about the issue” and failing even to attend a public hearing on it, Quinn “left little doubt . . . that she had been the driving force behind the deal.” It's pretty official when the Times calls it a deal.

Speaker Quinn had no answers about the Chelsea Market plan’s zoning merits because there are none. So how was the proposal approved? By a system that promises more of the same. Speaker Quinn’s and the City Council’s votes are part of ULURP, the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure that’s supposed to let the public and city officials participate in reviewing and approving development. In theory, the review process begins when a project is certified by the Department of City Planning. In practice, certification by the Department guarantees a project will go forward, rendering ULURP pointless except to provide a retroactive veneer of democratic process. Only one project in recent memory has been certified and not built, and that was under atypical circumstances. City officials and community board members who weigh in under ULURP can’t vote an unqualified “no” on a project without being ostracized for refusing to play ball and losing the chance to earn give-backs. On the Chelsea Market proposal, for example, Community Board 4 voted “no, unless” Jamestown funded off-site affordable housing. Several of Chelsea Market’s ULURP participants told me that voting the flat “no” in their heart would be futile and waste a chance to salvage some community benefit. After ULURP, City Planning can count such forced hands as raised in support. The system is perfectly rigged to cloud responsibility and foster deals. Projects may be scaled back during ULURP, but developers can pad their projects in anticipation. The Chelsea Market proposal has been scaled back slightly, creating an illusion of a functioning review process that Speaker Quinn and the Department of City Planning can cheaply trumpet.

Officials involved in ULURP seem desperate for any tweak or offset to deflect community criticism and make them appear to have done right by the public, while approving projects regardless of merit like the political animals they are. In meetings I and other community members had with Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer and Speaker Quinn during their respective turns at ULURP deliberation, we were pressed from the start to tell what concessions or give-backs would satisfy us. Both Stringer and Quinn were more interested in making the project palatable to us than hearing why it shouldn’t be built. The Borough President and members of his impressive land-use staff, who are a credit to him, grasped the proposal’s lack of merit and its motivation in greed to cash in on views over the High Line. Despite this worthy analysis, ULURP’s political reality apparently prevented the Borough President's flat rejection. At least he acknowledged the lunacy of building over the High Line, voting “no, unless” Jamestown’s addition was shifted to the Ninth Avenue end of Chelsea Market and scaled back. If City Planning was really interested in such informed ULURP input, it wouldn’t have ignored the detailed and compelling substance of the Borough President’s recommendations. City Planning left most of the addition over the High Line in its own later recommendations.

Permission to build above the High Line was clearly set in stone from the start, as witnessed by its survival though a review process that sometimes spotlighted its zoning folly. If this was one side of a deal that had to be honored, the other was Jamestown’s payout of about $17 million into a High Line maintenance fund. To those who see Jamestown’s proposal as simply wrong, no give-backs can make it right. Accepting them would be like allowing wrongdoing on Wall Street for a cut of the action. To the extent that Friends of the High Line was in on the ground floor of such a deal, it can be said to have encouraged zoning abuse for financial gain. It shares both spoils and blame with Jamestown. City Planning created some cover for this in September, when it diverted $4.7 million of Jamestown’s payout into affordable housing, answering Community Board 4’s earlier approval condition. (Housing experts say such funding promises often grease zoning changes through without ever producing new affordable units.) To some, this diversion of funds only reinforced the impression of a deal by seeming to explain the earlier surprise appropriation of $5 million to the High Line by the City Council in June’s city budget agreement. In July, Matt Katz of DNAinfo wrote that “The move has some park advocates questioning why the city is set to spend on the High Line such a large part of its $105 million, 2013 appropriations for 142 park projects — when the taxpayer money could go to other city parks that have greater infrastructure needs and fewer wealthy donors.” Factoring in this gift from Speaker Quinn’s City Council, the High Line’s $17 million side of the deal should be preserved.

What else but a deal could explain Robert Hammond’s perverse cheerleading for Jamestown’s tower over the High Line? His park would have earned just as big a payout if Jamestown built its whole project at the far end of Chelsea Market, where it wouldn’t rob the High Line of sunlight, sky views and open space, and would sensibly be closer to subways and Google's headquarters. Jamestown critically needed Hammond as a spokesman, which he must have agreed to be from the start. He dutifully told whoppers for Jamestown at the City Planning ULURP hearing on July 25th, testifying that “The High Line was designed to interact with neighborhood buildings, even changes in the skyscape that take place around it.” (Never mind that the skyline immediately around Chelsea Market was deliberately sculpted by existing zoning to complement the current height of Chelsea Market at a critical location.) City Planning Chair Amanda Burden beamed at Hammond as he explained, “People love architectural variations around the High Line. We don’t think they’ll detract from the experience of being on the High Line at all.” As for shadows Jamestown’s tower will cast on the High Line, Hammond said people seek shade underneath the High Line as it is. (Never mind that the tower will cast its longest shadows in colder months, putting most of the park’s Tenth Avenue Square grandstand feature in shadow when warming sunlight would increase its use.) Hammond even said High Line visitors won’t see Jamestown’s tower because the grandstand faces away from it, paying Jamestown’s design the highest praise it's earned to date.

Robert Hammond is a folk hero and the apple of Amanda Burden’s eye for having conceived of the High Line, but its success now has many legitimate fathers. These include talented architects and dedicated advocates like Ed Kirkland, who helped create the park and was the primary author of the Special West Chelsea District zoning which protects High Line open space and reduces the height of new development as it approaches historic surroundings. In a recent New York Times profile, the 87 year-old Mr. Kirkland said of Jamestown’s proposal, “I promise that there is no reason for this to happen except financial reasons that benefit Jamestown. It does not do the city or Chelsea any good. It’s bad for the High Line . . .” There’s no better authority; for fifty years, no one has given as much of himself as Mr. Kirkland to Chelsea’s preservation and planning. "If I wasn’t used to the city, I would be outraged," he added in a public forum on October 18th.

The High Line was also created with over a hundred million dollars in public funding, making stakeholders of all New Yorkers. Although Robert Hammond doesn’t seem to appreciate the value of others’ High Line contributions, he’s been uniquely entrusted to barter them. He also seems unaware of the backlash that may come of the ugly spectacle he’s created: Jamestown shoving past the public to hog prime space on a High Line it sees as a money-trough. The damage isn’t limited to the High Line. Chelsea’s residential character and historic authenticity will suffer, and the neighborhood made more like Times Square, a place of office towers and tourists, avoided by New Yorkers. Like Chelsea Market’s historic sensitivity, the rest of Chelsea is forgotten under the reigning High Line mania. Hammond’s failed 2009 attempt to have neighboring blocks taxed for High Line operating costs still rankles in Chelsea. In a public meeting on Jamestown's plan last year, Community Board 4’s Corey Johnson voiced a growing neighborhood mood, repeating, “I resent having the High Line used against us.”

Most New Yorkers I speak to are still unaware of what’s planned for Chelsea Market, but it’s coming soon, in 3D. There will be many a “who let that happen?” Frank Lloyd Wright claimed his buildings were portraits of his clients. Has Jamestown's architect, David Burns of STUDIOS Architecture, made his Chelsea Market design a group portrait of those behind the project? Maybe he's a better architect than we think.

ULURP promises more ugly pictures. As Speaker Quinn’s lack of answers attests, the process isn’t about responsible planning, but deals. ULURP reform cries out to be made an issue in the upcoming mayoral campaign. After what she's condoned at Chelsea Market, it’s not a cause Quinn can claim. After so bitterly letting down her own council district, one wonders just what she can claim to the rest of New York.

While Chelsea Market is a lost cause, it may be a big enough outrage to rally change, like Penn Station’s demolition, which was just as foolishly justified by the promise of jobs.

From right to left, Amanda Burden, Christine Quinn, Mayor Bloomberg and Boss Tweed reprise Thomas Nast's ring of passed blame around Chelsea Market in a flyer that's started appearing on Chelsea streets.

On October 19th, I and others met with City Council Speaker Christine Quinn to discuss Jamestown Properties’ proposed rezoning of Chelsea Market, aimed at adding over a quarter-million square feet of office space to the historic complex. I twice asked Speaker Quinn just how she saw the proposal making sense on zoning basics of use, bulk or environmental impact. She would only say that she hadn’t completed her review, but then still had no answer when we met six days later, just before the City Council's land-use committee voted to support the proposal, surely with Quinn's endorsement. Only Speaker Quinn could have stopped the project, but she advanced it in the face of overwhelming community resistance and without being able to say how it was good zoning.

If Speaker Quinn is already beholden to real estate interests in her expected run for mayor next year, she promises to bring to that office a fourth term of the Bloomberg administration’s worst feature; a pro-development, anti-oversight bias. In this New York, real estate runs politics and deals trump zoning. In a New York Times article on the Council's Chelsea Market vote, David Chen wrote that in remaining “conspicuously quiet about the issue” and failing even to attend a public hearing on it, Quinn “left little doubt . . . that she had been the driving force behind the deal.” It's pretty official when the Times calls it a deal.

Speaker Quinn had no answers about the Chelsea Market plan’s zoning merits because there are none. So how was the proposal approved? By a system that promises more of the same. Speaker Quinn’s and the City Council’s votes are part of ULURP, the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure that’s supposed to let the public and city officials participate in reviewing and approving development. In theory, the review process begins when a project is certified by the Department of City Planning. In practice, certification by the Department guarantees a project will go forward, rendering ULURP pointless except to provide a retroactive veneer of democratic process. Only one project in recent memory has been certified and not built, and that was under atypical circumstances. City officials and community board members who weigh in under ULURP can’t vote an unqualified “no” on a project without being ostracized for refusing to play ball and losing the chance to earn give-backs. On the Chelsea Market proposal, for example, Community Board 4 voted “no, unless” Jamestown funded off-site affordable housing. Several of Chelsea Market’s ULURP participants told me that voting the flat “no” in their heart would be futile and waste a chance to salvage some community benefit. After ULURP, City Planning can count such forced hands as raised in support. The system is perfectly rigged to cloud responsibility and foster deals. Projects may be scaled back during ULURP, but developers can pad their projects in anticipation. The Chelsea Market proposal has been scaled back slightly, creating an illusion of a functioning review process that Speaker Quinn and the Department of City Planning can cheaply trumpet.

Officials involved in ULURP seem desperate for any tweak or offset to deflect community criticism and make them appear to have done right by the public, while approving projects regardless of merit like the political animals they are. In meetings I and other community members had with Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer and Speaker Quinn during their respective turns at ULURP deliberation, we were pressed from the start to tell what concessions or give-backs would satisfy us. Both Stringer and Quinn were more interested in making the project palatable to us than hearing why it shouldn’t be built. The Borough President and members of his impressive land-use staff, who are a credit to him, grasped the proposal’s lack of merit and its motivation in greed to cash in on views over the High Line. Despite this worthy analysis, ULURP’s political reality apparently prevented the Borough President's flat rejection. At least he acknowledged the lunacy of building over the High Line, voting “no, unless” Jamestown’s addition was shifted to the Ninth Avenue end of Chelsea Market and scaled back. If City Planning was really interested in such informed ULURP input, it wouldn’t have ignored the detailed and compelling substance of the Borough President’s recommendations. City Planning left most of the addition over the High Line in its own later recommendations.

Permission to build above the High Line was clearly set in stone from the start, as witnessed by its survival though a review process that sometimes spotlighted its zoning folly. If this was one side of a deal that had to be honored, the other was Jamestown’s payout of about $17 million into a High Line maintenance fund. To those who see Jamestown’s proposal as simply wrong, no give-backs can make it right. Accepting them would be like allowing wrongdoing on Wall Street for a cut of the action. To the extent that Friends of the High Line was in on the ground floor of such a deal, it can be said to have encouraged zoning abuse for financial gain. It shares both spoils and blame with Jamestown. City Planning created some cover for this in September, when it diverted $4.7 million of Jamestown’s payout into affordable housing, answering Community Board 4’s earlier approval condition. (Housing experts say such funding promises often grease zoning changes through without ever producing new affordable units.) To some, this diversion of funds only reinforced the impression of a deal by seeming to explain the earlier surprise appropriation of $5 million to the High Line by the City Council in June’s city budget agreement. In July, Matt Katz of DNAinfo wrote that “The move has some park advocates questioning why the city is set to spend on the High Line such a large part of its $105 million, 2013 appropriations for 142 park projects — when the taxpayer money could go to other city parks that have greater infrastructure needs and fewer wealthy donors.” Factoring in this gift from Speaker Quinn’s City Council, the High Line’s $17 million side of the deal should be preserved.