The Small House Lab Blog

House Design by Diagram, from Palladio to Kahn - Part 2

Continued from Part 1

The Trenton Bath House’s services are positioned at the corners of each of its major spaces, echoing the four stairs surrounding the central hall of the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio’s Villa Rotunda. The bath house’s plan also follows Palladio’s example in its basis in a diagram; in this case a “tartan grid,” as it’s become known to architects for its plaid appearance. Alternating 22-foot and 8-foot bands intersect to define large and small square spaces. The smaller spaces, highlighted above, contain toilets, storage rooms and U-shaped privacy passages leading to shower rooms.

An eight-foot square storage column in the background supports one of the bath house’s roofs at its corner. In the foreground, an eight-foot square U-turning privacy passage forms another hollow column.

Where the bath house’s hollow columns aren’t freestanding, they’re defined by vertical expansion joints and slightly raised 8-foot square concrete-slab caps. This allows the organizational logic of the building to be read and lets the columns contribute to its visual composition.

The bath house’s roofs float free between the hollow columns at their corners, expressing the liberation of the areas they serve.

Within the bath house’s privacy-screened shower pavilions, a primitive human relation to light, open air and nature is retained by sky openings around the perimeter of the roof and at its center. The absence of architectural detail and plainness of the concrete block, its crude joints deliberately struck flush, defer to this priority. The more self-effacing the surface upon which light falls, the more it seems to distill itself into its own primal mystery. The bath house’s architecture is less about itself than such fundamentals of nature and human experience, to which it reconnects the building’s users by removing distractions. This too recalls Palladio, whose villas were made of modest plastered brick, their power and luxury a matter of idealized form, not rich material. Kahn’s obsessive integration of services isn’t just a personality tic or a handy practical strategy; it’s a way to make a clearing for the wonder of existence to emerge. Kahn is renowned for his mastery of both the mundane and heavenly sides of this task.

Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Kahn was said by colleagues to have fixated on the illustration above, from Rudolf Wittkower’s 1949 book, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (John Wiley & Sons). It shows schematized plans of Palladio Villas next to a diagram discerned by Wittkower to be their basis. Massaging the bay widths of the grid and selectively deleting line segments yields the various plans. The grid’s left-to-right bands alternate in width, allowing a complex mix of large and small spaces to emerge. Without divulging this secret recipe, Palladio described his intention in The Four Books of Architecture. As translated by Isaac Ware in his 1738 English edition, Palladio wrote:

Palladio’s idea of reciprocally used main and supporting spaces was echoed by Kahn in a 1961 interview:

Now when I did the . . . Trenton Bath House, I discovered a very simple thing. I discovered that certain spaces are very unimportant and some spaces are the real raison d’etre for doing what you’re doing. But the small spaces were contributing to the strength of the larger spaces. They were serving them.

Kahn’s concept of mutually defining served and servant spaces is his major contribution to architectural thought. This idea and its diagrammatic implementation had been there all along, but Kahn broke new ground in using them to deliver architecture’s historic monumentality and primitive power into our age of finicky programmatic demands and technological complications.

An interpretation of Rudolf Wittkower’s grid is here overlaid in yellow on Palladio’s 1560 Villa Foscari, “La Malcontenta,” as published in The Four Books of Architecture. The villa’s plan is formed by dropping out six of the grid’s line segments. Using the grid as a starting point, Palladio consistently produced villas made up of perfectly formed rooms of varying shapes and sizes, all meshing into a perfect whole. As the villa walls were all load-bearing, the pattern also automatically created a workable system of structural bays. The vaulted ceiling at the center of La Malcontenta illustrates his method’s marriage of structure and form. The pattern’s alternation of wide and narrow zones would be adopted by later architects to integrate modern services, as foreshadowed by Palladio’s use of it to unintrusively absorb stairs and storerooms.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1893-94 Winslow House compactly internalizes small service spaces for kitchen, pantry, stairs, driveway entrance and storage without compromising the integrity of its larger living spaces or the house as a whole.

The same grid pattern discovered by Wittkower in Palladio’s villas could be seen to organize the Winslow House plan, demonstrating the strategy’s adaptability to the machine age. Wright routinely used geometric patterns to absorb modern services within coherent house plans.

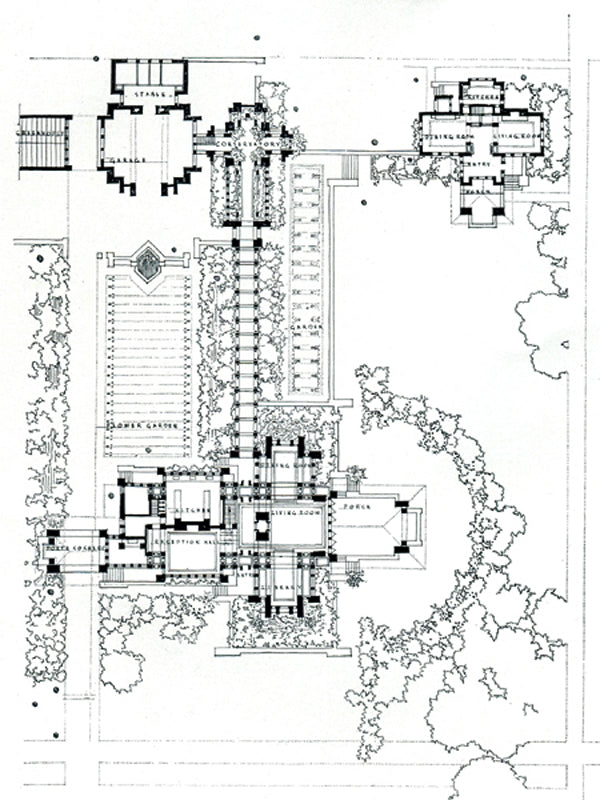

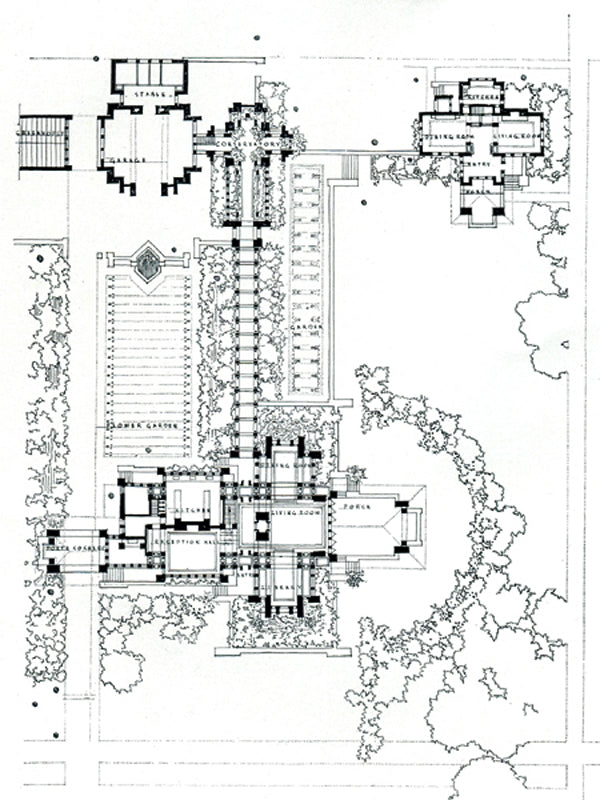

Wright later made extensive use of tartan grids to compose his much more complicated, magisterial Martin House complex.

Wright’s achievement can be appreciated by comparison to the design of “A Lake or River Villa for a Picturesque Site,” published 43 years earlier, in Andrew Jackson Downing’s 1850 house prototype book, The Architecture of Country Houses. The villa’s arrangement of perfectly shaped main rooms is achieved only by tacking on the messy services of kitchen, laundry and storage in an afterthought of a rear wing. This wing hides behind the house and, in the floor plan drawing, even sneaks off the page before fully revealing itself. The villa’s designer is clearly in denial about modern services and the compositional difficulty they present, so he exiles them from the major spaces they serve. Had he started from a Palladian grid or any other pattern accommodating large and small spaces, this might have been avoided. Instead of starting with a comprehensive diagram simultaneously arraying served and servant spaces, the villa’s designer planted spaces in sequence. He first arranged four full-sized rooms in a cruciform layout, then placed the stair tower in a notch to create a front façade of picturesque asymmetry, then realized there was no place for service spaces and hid them out back. A designer using this kind of sequential approach further limits his options with each successive decision. He favors the first functions to be placed and then progressively paints himself into a corner, forcing the last functions into arbitrary, leftover space. Today’s developer floor plans can somehow manage to look like entirely leftover space. It’s hard to point out any one thing that’s wrong with them; what they lack is what their designers lack; an architectural education.

This isn’t to say a good house can’t be designed without a diagram. Richard Neutra’s houses are free verse masterpieces. Neutra was a genius, though, and sculpted his designs around specific clients and sites. Prototype houses like Palladio’s villas aim for the universality of platonic ideals. They are embedded with ideas meant to apply anywhere, and to aid everyman. Louis I. Kahn has given these lessons new pertinence. Next, we’ll look at a house he designed, returning Palladio’s diagrammatic method to its original domestic realm.

House Design by Diagram, from Palladio to Kahn - Part 2

Continued from Part 1

The Trenton Bath House’s services are positioned at the corners of each of its major spaces, echoing the four stairs surrounding the central hall of the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio’s Villa Rotunda. The bath house’s plan also follows Palladio’s example in its basis in a diagram; in this case a “tartan grid,” as it’s become known to architects for its plaid appearance. Alternating 22-foot and 8-foot bands intersect to define large and small square spaces. The smaller spaces, highlighted above, contain toilets, storage rooms and U-shaped privacy passages leading to shower rooms.

An eight-foot square storage column in the background supports one of the bath house’s roofs at its corner. In the foreground, an eight-foot square U-turning privacy passage forms another hollow column.

Where the bath house’s hollow columns aren’t freestanding, they’re defined by vertical expansion joints and slightly raised 8-foot square concrete-slab caps. This allows the organizational logic of the building to be read and lets the columns contribute to its visual composition.

The bath house’s roofs float free between the hollow columns at their corners, expressing the liberation of the areas they serve.

Within the bath house’s privacy-screened shower pavilions, a primitive human relation to light, open air and nature is retained by sky openings around the perimeter of the roof and at its center. The absence of architectural detail and plainness of the concrete block, its crude joints deliberately struck flush, defer to this priority. The more self-effacing the surface upon which light falls, the more it seems to distill itself into its own primal mystery. The bath house’s architecture is less about itself than such fundamentals of nature and human experience, to which it reconnects the building’s users by removing distractions. This too recalls Palladio, whose villas were made of modest plastered brick, their power and luxury a matter of idealized form, not rich material. Kahn’s obsessive integration of services isn’t just a personality tic or a handy practical strategy; it’s a way to make a clearing for the wonder of existence to emerge. Kahn is renowned for his mastery of both the mundane and heavenly sides of this task.

Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Kahn was said by colleagues to have fixated on the illustration above, from Rudolf Wittkower’s 1949 book, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (John Wiley & Sons). It shows schematized plans of Palladio Villas next to a diagram discerned by Wittkower to be their basis. Massaging the bay widths of the grid and selectively deleting line segments yields the various plans. The grid’s left-to-right bands alternate in width, allowing a complex mix of large and small spaces to emerge. Without divulging this secret recipe, Palladio described his intention in The Four Books of Architecture. As translated by Isaac Ware in his 1738 English edition, Palladio wrote:

Palladio’s idea of reciprocally used main and supporting spaces was echoed by Kahn in a 1961 interview:

Now when I did the . . . Trenton Bath House, I discovered a very simple thing. I discovered that certain spaces are very unimportant and some spaces are the real raison d’etre for doing what you’re doing. But the small spaces were contributing to the strength of the larger spaces. They were serving them.

Kahn’s concept of mutually defining served and servant spaces is his major contribution to architectural thought. This idea and its diagrammatic implementation had been there all along, but Kahn broke new ground in using them to deliver architecture’s historic monumentality and primitive power into our age of finicky programmatic demands and technological complications.

An interpretation of Rudolf Wittkower’s grid is here overlaid in yellow on Palladio’s 1560 Villa Foscari, “La Malcontenta,” as published in The Four Books of Architecture. The villa’s plan is formed by dropping out six of the grid’s line segments. Using the grid as a starting point, Palladio consistently produced villas made up of perfectly formed rooms of varying shapes and sizes, all meshing into a perfect whole. As the villa walls were all load-bearing, the pattern also automatically created a workable system of structural bays. The vaulted ceiling at the center of La Malcontenta illustrates his method’s marriage of structure and form. The pattern’s alternation of wide and narrow zones would be adopted by later architects to integrate modern services, as foreshadowed by Palladio’s use of it to unintrusively absorb stairs and storerooms.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1893-94 Winslow House compactly internalizes small service spaces for kitchen, pantry, stairs, driveway entrance and storage without compromising the integrity of its larger living spaces or the house as a whole.

The same grid pattern discovered by Wittkower in Palladio’s villas could be seen to organize the Winslow House plan, demonstrating the strategy’s adaptability to the machine age. Wright routinely used geometric patterns to absorb modern services within coherent house plans.

Wright later made extensive use of tartan grids to compose his much more complicated, magisterial Martin House complex.

Wright’s achievement can be appreciated by comparison to the design of “A Lake or River Villa for a Picturesque Site,” published 43 years earlier, in Andrew Jackson Downing’s 1850 house prototype book, The Architecture of Country Houses. The villa’s arrangement of perfectly shaped main rooms is achieved only by tacking on the messy services of kitchen, laundry and storage in an afterthought of a rear wing. This wing hides behind the house and, in the floor plan drawing, even sneaks off the page before fully revealing itself. The villa’s designer is clearly in denial about modern services and the compositional difficulty they present, so he exiles them from the major spaces they serve. Had he started from a Palladian grid or any other pattern accommodating large and small spaces, this might have been avoided. Instead of starting with a comprehensive diagram simultaneously arraying served and servant spaces, the villa’s designer planted spaces in sequence. He first arranged four full-sized rooms in a cruciform layout, then placed the stair tower in a notch to create a front façade of picturesque asymmetry, then realized there was no place for service spaces and hid them out back. A designer using this kind of sequential approach further limits his options with each successive decision. He favors the first functions to be placed and then progressively paints himself into a corner, forcing the last functions into arbitrary, leftover space. Today’s developer floor plans can somehow manage to look like entirely leftover space. It’s hard to point out any one thing that’s wrong with them; what they lack is what their designers lack; an architectural education.

This isn’t to say a good house can’t be designed without a diagram. Richard Neutra’s houses are free verse masterpieces. Neutra was a genius, though, and sculpted his designs around specific clients and sites. Prototype houses like Palladio’s villas aim for the universality of platonic ideals. They are embedded with ideas meant to apply anywhere, and to aid everyman. Louis I. Kahn has given these lessons new pertinence. Next, we’ll look at a house he designed, returning Palladio’s diagrammatic method to its original domestic realm.

House Design by Diagram, from Palladio to Kahn - Part 1

Photo courtesy Louis I. Kahn Collection, The University of Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

Louis I. Kahn’s Trenton Bath House holds an outsize place in the history of modern architecture. It was built in 1955 to serve a community center swimming pool outside the New Jersey city. In its design, some of the renowned architect’s most influential ideas coalesced. “I discovered myself after designing that little concrete block bathhouse in Trenton,” Kahn would say in a 1970 interview. Its planning principles are of great use in house design and appear to have evolved from the tradition of prototype houses. The photo of the newly completed Bath House above, taken by Kahn’s office, highlights its primitive power based on primary shapes. The building’s pyramid roofs are truncated to create sky openings that recall the temple space of the Pantheon. The circular pebble garden in the foreground has a mystical resonance. It may also mark the source of the Bath House’s lineage as the 16th century Villa Rotunda.

Andrea Palladio’s Villa Rotunda adopts the symmetry, porticoes and triangular pediments of ancient temples. It is unique among Palladio's villas in having a temple portico on every facade. The architect's use of such features in Renaissance villa designs of the late 1500s influenced the shape of houses through 18th century English manors to 21st century American housing tracts. Palladio was dedicated to classical precedents but lived before the rediscovery and excavation of the ancient house in Pompeii. He made his own assumptions about residential design in antiquity, arguing that the surviving temples of the Romans must have evolved from their vanished homes. These houses would thus have been scaled-down temples. This contradicted descriptions by historical sources like Vitruvius, but conveniently allowed Palladio to indulge his temple-class spatial aspirations and composition skills on original villa designs, without denying them a claim to a classical pedigree. Pompeii’s rediscovery in 1599 showed that ancient homes were low-slung courtyard houses free of pediments and porticoes. America’s White House and countless other Palladian spin-offs are thus based on a historical misconception. Palladio’s hugely appealing house forms would start a history all their own.

Palladio’s villa designs make up the second of his Four Books of Architecture and might be called one of the very first house plan books. Palladio’s treatise has been the greatest single influence on Western architecture since its publication in 1570. Thomas Jefferson called it “the Bible,” and was guided by it in designing Monticello and the University of Virginia. As illustrated in the Four Books above, Palladio’s Villa Rotunda has a double-height central hall with a circular plan ordained by the dome which crowns it. This main space is surrounded by smaller, subsidiary one-story rooms, and then porticoes and outside stairs in a cruciform pattern radiating from the central circle. The house stands on a hilltop and its exterior stairs further elevate its main level, from the center of which there are views outside in all directions. The roughly triangular masses between the circular center room and its square outer frame add structural support to the dome above. They are also hollowed out to contain four stairs. This keeps the stairs from disturbing the pure forms of the other rooms or the symmetrical ideal of the house. They fall within the wall thickness, the “poché,” to use the French architectural term for this typically shaded zone into which pockets of support space are sometimes carved. This stair solution is both practical and part of a much loftier agenda. Palladio scholar Robert Tavernor, in his 1991 book, Palladio and Palladianism, has commented on the villa’s square-inscribed central circle:

The circle was the Pythagorean symbol of unified perfection, infinity and deity: indeed, it symbolized virtue to the early Christians. The square, conversely, was equated with the physical universe and the material world. Attempts at ‘squaring the circle,’ from the Pythagoreans onward, reflect the desire to reduce infinity to something finite, or to transmute the divine to the physical realm. What could be more appropriate for the Villa Rotunda, which with its perfect natural setting, outward symmetry and temple-like appearance comes closer than any other to Palladio’s ideal for the villa?

The Neo-Palladian architect Colen Campbell published his own influential architectural treatise, Vitruvius Britannicus, in the early 18th century. It chronicled two centuries of British architecture and promoted Palladianism. The collection included Campbell’s own enlarged update of the Villa Rotunda, Mereworth Castle, built in Kent, England, in 1723. Its upper floor plan is at left above, and its main floor at right. Campbell retained Palladio’s focal squared circle, but filled only two of its hollowed corners with stairs, making bedroom closets of the other two, and, on the upper level, a passage into the rotunda gallery. His varied use of these spaces has implications for the design’s potential as a prototype. Pre-loaded into a model house diagram, such flexible cavities might absorb alternate or evolving services with no effect on the formal spaces which the design is primarily about.

Campbell’s contemporary, James Gibbs, published A Book of Architecture in 1728. It presented his own built and theoretical designs as examples “of use to such gentlemen as might be concerned in building, especially in the remote parts of the country, where little or no assistance for designs can be procured.” The book was thus at once a monograph of Gibbs’ work and a pattern book of prototypes. Plate 44 of the book, above, shows a model “House made for a Gentleman.” Its idealized plan is like that of the Villa Rotunda, but arranged into a nine-square tic-tac-toe grid with a strong cruciform undercurrent. The squares to the right and left of the central hall are precisely dedicated to service rooms and circulation. Palladio’s central circle is here rendered an octagon, and in the corners around it where Palladio buried stairs, Gibbs places short, shunting corridors to give his gentleman’s servants direct, screened access from the support areas to each of the main rooms. Gibbs’ plan makes for such a decorative visual pattern that its basis in a master-servant social order and discrete servicing might escape notice. His section drawing through the house emphasizes the central hall's primacy, a master space shaped and supported by the spaces around it.

A garden pavilion from Gibbs' book closely follows the example of centrally planned Renaissance churches like Giuliano da Sangallo's Santa Maria Delle Carceri. Its boxed circle within a Greek cross could also be the kernel of the Villa Rotunda and its offspring.

In his design for the Trenton Bath House, Kahn seemed to pick up Gibbs' thread centuries later. The Villa Rotunda's venerable squared circle remains, but Palladio's lofty center hall is now an echo expressed in a circular pebble garden, domed by the sky. With the Bath House, Kahn brought Palladio's explorations full circle to the courtyard form of a historically accurate Roman house. The four wings of the Bath House's Greek cross become square pavilions topped by pyramid roofs. The roofs are supported at each corner on a square concrete pad topping an 8-foot square hollow column, open on one side for access.

The hollow columns at the corners of the central circle house U-shaped privacy passages – “baffles,” Kahn called them - leading into the men’s and women’s shower pavilions on each side. These columns house circulation within structure at the corners of the squared circled, just as the Villa Rotunda’s hollowed-out corner masses did in the same arrangement. Kahn’s baffles are even more like Gibbs’ skewed, servant-screening passageways around the central hall of the House for a Gentleman. Kahn repeated this approach at the corners of each of the four pavilions, supporting their roofs with hollow columns containing storage or toilets where they didn’t hold baffles. This recalls the stair- or storage-housing versatility of Colen Campbell’s hollowed corner masses around the rotunda at Mereworth Castle. It also makes each of the Bath House’s square pavilions a Palladian rotunda, supported at the corners by hollow, service-containing structure. The self-contained pyramid roof over each square stands in for the rotunda dome.

Absorbing all of the structural and utilitarian needs of the Bath House, Kahn’s hollow columns leave undisturbed the lofty spaces defined by the open pyramid roofs. Kahn described his priorities in his 1959 Talk at the Conclusion of the Otterlo Congress:

The architect must find a way in which the serving areas of a space can be there, and still not destroy his spaces. He must find a new column, he must find a new way of making those things work, and still not lose his building on a podium. But you cannot think of it as being one problem, and the other things as being another problem.

Actually, these are wonderful revelations because modern space is really not different from Renaissance space.

There’s no indication that Colen Campbell or James Gibbs were conscious influences on Kahn as he designed the Bath House, although his formal education would have exposed him to the mainstream of architectural history in which they figure. It is known that Kahn had Palladio in mind; his personal notebook from the time, on a page marked “Palladian Plan,” records his thoughts on rooms defined by structural bays. He was also known to be fascinated by a particular study of Palladio’s villas in a recent book. The architect and educator William S. Huff was a student of Kahn’s and worked in his office in the 1950s. In a 1981 article, “Sorted Recollections and Lapses in Familiarities,” Huff wrote:

At that time too, an important book came out – Wittkower’s Architectural Principals in the Age of Humanism. Everyone fell over himself to try to grasp it. Palladio was raised to new interest. Palladio meant one thing to Philip [Johnson] - it meant things about proportion and composition. Lou discovered something else in Palladio.

In Palladio, Lou saw the “servant” spaces. He saw that the Villa Rotunda was a great space which he called the “master space” and which was served and surrounded by spaces where the servants were. Kahn saw the analogy with modern times. We no longer have rooms with human servants in them. We now have many spaces with mechanical servants that do the same work that human servants used to do.

So, one of the great principles of Kahn’s architecture, which was formulated about this time, came from his unique way of looking at Palladio.

The Bath House's heavy dependence on plumbing made it a perfect test of Palladio's modern pertinence, which would be proven by Kahn's making it a temple. It follows a long tradition of buildings inspired by the Villa Rotunda and, like earlier examples, carries lessons for others.

Next, we’ll take a further look at Kahn’s interpretation of Palladian principles and explore their application to modern house design.

House Design by Diagram, from Palladio to Kahn - Part 1

Photo courtesy Louis I. Kahn Collection, The University of Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

Louis I. Kahn’s Trenton Bath House holds an outsize place in the history of modern architecture. It was built in 1955 to serve a community center swimming pool outside the New Jersey city. In its design, some of the renowned architect’s most influential ideas coalesced. “I discovered myself after designing that little concrete block bathhouse in Trenton,” Kahn would say in a 1970 interview. Its planning principles are of great use in house design and appear to have evolved from the tradition of prototype houses. The photo of the newly completed Bath House above, taken by Kahn’s office, highlights its primitive power based on primary shapes. The building’s pyramid roofs are truncated to create sky openings that recall the temple space of the Pantheon. The circular pebble garden in the foreground has a mystical resonance. It may also mark the source of the Bath House’s lineage as the 16th century Villa Rotunda.

Andrea Palladio’s Villa Rotunda adopts the symmetry, porticoes and triangular pediments of ancient temples. It is unique among Palladio's villas in having a temple portico on every facade. The architect's use of such features in Renaissance villa designs of the late 1500s influenced the shape of houses through 18th century English manors to 21st century American housing tracts. Palladio was dedicated to classical precedents but lived before the rediscovery and excavation of the ancient house in Pompeii. He made his own assumptions about residential design in antiquity, arguing that the surviving temples of the Romans must have evolved from their vanished homes. These houses would thus have been scaled-down temples. This contradicted descriptions by historical sources like Vitruvius, but conveniently allowed Palladio to indulge his temple-class spatial aspirations and composition skills on original villa designs, without denying them a claim to a classical pedigree. Pompeii’s rediscovery in 1599 showed that ancient homes were low-slung courtyard houses free of pediments and porticoes. America’s White House and countless other Palladian spin-offs are thus based on a historical misconception. Palladio’s hugely appealing house forms would start a history all their own.

Palladio’s villa designs make up the second of his Four Books of Architecture and might be called one of the very first house plan books. Palladio’s treatise has been the greatest single influence on Western architecture since its publication in 1570. Thomas Jefferson called it “the Bible,” and was guided by it in designing Monticello and the University of Virginia. As illustrated in the Four Books above, Palladio’s Villa Rotunda has a double-height central hall with a circular plan ordained by the dome which crowns it. This main space is surrounded by smaller, subsidiary one-story rooms, and then porticoes and outside stairs in a cruciform pattern radiating from the central circle. The house stands on a hilltop and its exterior stairs further elevate its main level, from the center of which there are views outside in all directions. The roughly triangular masses between the circular center room and its square outer frame add structural support to the dome above. They are also hollowed out to contain four stairs. This keeps the stairs from disturbing the pure forms of the other rooms or the symmetrical ideal of the house. They fall within the wall thickness, the “poché,” to use the French architectural term for this typically shaded zone into which pockets of support space are sometimes carved. This stair solution is both practical and part of a much loftier agenda. Palladio scholar Robert Tavernor, in his 1991 book, Palladio and Palladianism, has commented on the villa’s square-inscribed central circle:

The circle was the Pythagorean symbol of unified perfection, infinity and deity: indeed, it symbolized virtue to the early Christians. The square, conversely, was equated with the physical universe and the material world. Attempts at ‘squaring the circle,’ from the Pythagoreans onward, reflect the desire to reduce infinity to something finite, or to transmute the divine to the physical realm. What could be more appropriate for the Villa Rotunda, which with its perfect natural setting, outward symmetry and temple-like appearance comes closer than any other to Palladio’s ideal for the villa?

The Neo-Palladian architect Colen Campbell published his own influential architectural treatise, Vitruvius Britannicus, in the early 18th century. It chronicled two centuries of British architecture and promoted Palladianism. The collection included Campbell’s own enlarged update of the Villa Rotunda, Mereworth Castle, built in Kent, England, in 1723. Its upper floor plan is at left above, and its main floor at right. Campbell retained Palladio’s focal squared circle, but filled only two of its hollowed corners with stairs, making bedroom closets of the other two, and, on the upper level, a passage into the rotunda gallery. His varied use of these spaces has implications for the design’s potential as a prototype. Pre-loaded into a model house diagram, such flexible cavities might absorb alternate or evolving services with no effect on the formal spaces which the design is primarily about.

Campbell’s contemporary, James Gibbs, published A Book of Architecture in 1728. It presented his own built and theoretical designs as examples “of use to such gentlemen as might be concerned in building, especially in the remote parts of the country, where little or no assistance for designs can be procured.” The book was thus at once a monograph of Gibbs’ work and a pattern book of prototypes. Plate 44 of the book, above, shows a model “House made for a Gentleman.” Its idealized plan is like that of the Villa Rotunda, but arranged into a nine-square tic-tac-toe grid with a strong cruciform undercurrent. The squares to the right and left of the central hall are precisely dedicated to service rooms and circulation. Palladio’s central circle is here rendered an octagon, and in the corners around it where Palladio buried stairs, Gibbs places short, shunting corridors to give his gentleman’s servants direct, screened access from the support areas to each of the main rooms. Gibbs’ plan makes for such a decorative visual pattern that its basis in a master-servant social order and discrete servicing might escape notice. His section drawing through the house emphasizes the central hall's primacy, a master space shaped and supported by the spaces around it.

A garden pavilion from Gibbs' book closely follows the example of centrally planned Renaissance churches like Giuliano da Sangallo's Santa Maria Delle Carceri. Its boxed circle within a Greek cross could also be the kernel of the Villa Rotunda and its offspring.

In his design for the Trenton Bath House, Kahn seemed to pick up Gibbs' thread centuries later. The Villa Rotunda's venerable squared circle remains, but Palladio's lofty center hall is now an echo expressed in a circular pebble garden, domed by the sky. With the Bath House, Kahn brought Palladio's explorations full circle to the courtyard form of a historically accurate Roman house. The four wings of the Bath House's Greek cross become square pavilions topped by pyramid roofs. The roofs are supported at each corner on a square concrete pad topping an 8-foot square hollow column, open on one side for access.

The hollow columns at the corners of the central circle house U-shaped privacy passages – “baffles,” Kahn called them - leading into the men’s and women’s shower pavilions on each side. These columns house circulation within structure at the corners of the squared circled, just as the Villa Rotunda’s hollowed-out corner masses did in the same arrangement. Kahn’s baffles are even more like Gibbs’ skewed, servant-screening passageways around the central hall of the House for a Gentleman. Kahn repeated this approach at the corners of each of the four pavilions, supporting their roofs with hollow columns containing storage or toilets where they didn’t hold baffles. This recalls the stair- or storage-housing versatility of Colen Campbell’s hollowed corner masses around the rotunda at Mereworth Castle. It also makes each of the Bath House’s square pavilions a Palladian rotunda, supported at the corners by hollow, service-containing structure. The self-contained pyramid roof over each square stands in for the rotunda dome.

Absorbing all of the structural and utilitarian needs of the Bath House, Kahn’s hollow columns leave undisturbed the lofty spaces defined by the open pyramid roofs. Kahn described his priorities in his 1959 Talk at the Conclusion of the Otterlo Congress:

The architect must find a way in which the serving areas of a space can be there, and still not destroy his spaces. He must find a new column, he must find a new way of making those things work, and still not lose his building on a podium. But you cannot think of it as being one problem, and the other things as being another problem.

Actually, these are wonderful revelations because modern space is really not different from Renaissance space.

There’s no indication that Colen Campbell or James Gibbs were conscious influences on Kahn as he designed the Bath House, although his formal education would have exposed him to the mainstream of architectural history in which they figure. It is known that Kahn had Palladio in mind; his personal notebook from the time, on a page marked “Palladian Plan,” records his thoughts on rooms defined by structural bays. He was also known to be fascinated by a particular study of Palladio’s villas in a recent book. The architect and educator William S. Huff was a student of Kahn’s and worked in his office in the 1950s. In a 1981 article, “Sorted Recollections and Lapses in Familiarities,” Huff wrote:

At that time too, an important book came out – Wittkower’s Architectural Principals in the Age of Humanism. Everyone fell over himself to try to grasp it. Palladio was raised to new interest. Palladio meant one thing to Philip [Johnson] - it meant things about proportion and composition. Lou discovered something else in Palladio.

In Palladio, Lou saw the “servant” spaces. He saw that the Villa Rotunda was a great space which he called the “master space” and which was served and surrounded by spaces where the servants were. Kahn saw the analogy with modern times. We no longer have rooms with human servants in them. We now have many spaces with mechanical servants that do the same work that human servants used to do.

So, one of the great principles of Kahn’s architecture, which was formulated about this time, came from his unique way of looking at Palladio.

The Bath House's heavy dependence on plumbing made it a perfect test of Palladio's modern pertinence, which would be proven by Kahn's making it a temple. It follows a long tradition of buildings inspired by the Villa Rotunda and, like earlier examples, carries lessons for others.

Next, we’ll take a further look at Kahn’s interpretation of Palladian principles and explore their application to modern house design.

Less Dwelling, More Living

Lily Copenagle and Jamie Kennel designed their house with help from SketchUp, the free, user-friendly 3D program that's also used for Small House Lab's 3D models. It brings new visualization and experimentation powers to the masses, facilitating owner participation in house design. (Image courtesy Lily Copenagle.)

Two weeks ago, a New York Times story called "Freedom in 704 Square Feet" reported on an Oregon couple who built a small house in part to free their lives for other pursuits:

The idea was simple. They would create a home that was big enough for the two of them, but small enough so that it would be easy to maintain, environmentally responsible and inexpensive to operate. And that would allow them to free up their time and funds for intellectual and recreational pursuits. Own less, live more . . .

Small House Lab was conceived on faith that such people existed. On the eve of this site’s launch, their story brought confirmation that they do. The Times story then topped the paper's most-viewed-online list in the week that followed, signaling that the Oregon couple may not be outliers but forerunners of a new type of homeowner.

And why wouldn’t they be? They’re in the demographic mainstream of today’s America, where 55% of households are of one or two people, and only 20% are a couple with a child at home. Roll over, Ozzie and Harriet. Why care for an oversized house and work to pay it off when you could be reading, volunteering for your favorite cause or bike-touring Greece? It’s human to fixate on visible possessions and overlook invisible, more precious time, but at life’s end it’s the sum of our experiences, not our possessions, that will fill out the scorecard. As the one-room-cabin dweller Thoreau wrote in Walden:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when it came to die, discover that I had not lived.

Were Lily Copenagle and Jamie Kennel swayed by Thoreau when they built their 704 square foot house? I asked this and other questions by email, and heard back that they aren’t particularly influenced by any philosopher or writer, but do “try to live thoughtfully,” and “don't have a need to demonstrate social status through the accumulation and display of stuff.” They’re not out to make statement or repudiate a culture of materialism and excess. The couple seems instead to have pragmatically derived their house from qualities they liked in their previous homes.

Their first dwelling was an 1100 square foot loft. They liked its openness, but with the four dogs they had between them when they met, they needed outdoor space. The next stop was an 860 square foot, 1910 bungalow “arranged as a series of lots of little rooms, and we found that all six of us just moved from one little room to another,” according to Lily Copenagle. They also weren’t vitally occupying the whole house but using parts for storage. “We didn't like the idea of heating and furnishing rooms just because they were there, so we started thinking about what our ideal floor plan and size would look like.” They then looked for either a smaller house with a simple layout or a rare vacant city lot. They found a 700 square foot 1950s house at the north end of an oversized 50’ by 150’ lot. It was hopelessly moldy but the right size and looked south onto a gigantic back yard. They bought the house, tore it down and built a spatially luxurious, loft-like one-room house on its foundation. A wall of south-facing windows floods the new house with light and visually extends its space down the length of the yard. The one-story new house will allow the couple to age in place.

While their parents were approving and supportive, Lily's mother once joked that the couple took down a perfectly good two-bedroom house and put up a room. She may not have realized what an architectural compliment she was paying. In his 1954 book, The Natural House, Frank Lloyd Wright criticized houses like the couple's earlier 1911 bungalow:

The interiors consisted of boxes beside or inside boxes, called rooms. All boxes were inside a complicated outside boxing.

Even before that bungalow was built, Wright’s 1908 essay, In the Cause of Architecture, had argued:

A building should contain as few rooms as will meet the conditions which give it rise and under which the architect should strive continually to simplify . . .

Wright recalls the “simplify, simplify” of Thoreau, whose one-room cabin at Walden Pond took room reduction to the limit. If a building has only one room, all its vitality is concentrated in a single space. Such buildings may tap the psychological force of primal architecture, invoking archetypal cave and hut dwellings or ancient temples. To quote the architect Frank Gehry: “Think of the power of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings are one-room buildings.” These structures have a satisfying interior-exterior unity and irreducible simplicity. Masterpiece examples range from the Pantheon to Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. The latter, like Philip Johnson’s Glass House and other modern-house touchstones, is a single room, not counting bathrooms. Notably, these are only weekend houses. In Portland, Lily and Jamie have pushed the envelope by building a one-room primary residence. Their contentment in it may be less a proof of its viability for typical couples than a tribute to their exceptional relationship. Asked how they get by without interior doors, Lily emailed:

We still both work very long hours for our jobs, and we find that when we're home we are glad that we can be together, even if one of us is cooking and the other is working in the office area. We enjoy each other's company (and that of our dogs, of course) so much, and we seem to have so much overlap between the way we want to be in the space that we don't have the conflicts that other couples say they feel they would have. We also just really enjoy being kind to each other.

Their house may explore new territory in urban planning as well. American city neighborhoods are full of moldering, energy-inefficient wood-framed houses with the dated, box-like interior compartmentalization Wright mocked over a century ago. These neighborhoods retain valuable infrastructure, services, mixed-use community character and walkable density – qualities attractive to anyone disaffected with car-dependent suburban blandness. As the Portland couple has demonstrated, these neighborhoods also have reusable house foundations and utility hook-ups. It’s tempting to envision old neighborhoods as incubators of self-designed lives in owner-built houses, as fields awaiting a new crop. For the average person, building one’s own house typically involves buying land and having enough funds left over to qualify for a construction loan. This can be financially challenging for those shopping among typically large suburban lots, where zoning often dictates conventional tract-house forms and sizes. Urban tear-down sites may offer both affordability and creative freedom, along with sidewalks and community.

Demolition needn’t be wasteful. Lily and Jamie donated or reused material from the house they replaced, throwing away only one dumpster-load. Their replacement house is far more energy efficient.

Lily Copenagle and Jamie Kennel's floor plan organizes bathroom, storage and sleeping spaces into a support zone along one side and aligns the kitchen counter and a desk against the opposite side, leaving the space between as a well-defined living pavilion. Not shown is a freestanding storage unit that screens the bulk of the living space from the front door, at top, without diminishing the house's one-room appeal. The New York Times piece about the house has a slideshow with photos. (Image courtesy Lily Copenagle.)

Thoreau may not have inspired the Portland couple, but he’d surely approve. He built his cabin at Walden Pond with his own hands as deliberately as he created his life in the woods. Walden is largely a critique of the American home, which Thoreau sees as overinflated with “empty guest chambers for empty guests.” His take on the reason: “Most men appear never to have considered what a house is, and are actually though needlessly poor all their lives because they think that they must have such a one as their neighbors have.” In Thoreau’s accounting, the dwelling is inversely proportional to the living. He defines the cost of a house as “the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.” For this reason, “when the farmer has got his house, he may not be the richer but the poorer for it, and it may be the house that has got him.” As the man who wrote, “Our life is frittered away by detail,” Thoreau would have approved of this design requirement for the Portland house reported in the Times story: “Ms. Copenagle wanted a space that was small enough to vacuum completely in five minutes, within cord’s reach of a single outlet, so there wouldn’t have to be any unplugging and replugging of the vacuum cleaner.”

Of course, Thoreau’s managing to live in a tiny one-room cabin isn’t the point of Walden. The cabin is more important as a demonstration of personal instrumentality, of actively replacing received convention with a self-made, authentic life. This applies to the little house in Portland, too. As Lily emailed:

I think that one of the things that's interesting to me about the response to the article was that people seem to be relatively focused on the size, which is understandable, but what I wish other people were catching on to more was the extent to which we did this ourselves. . . . I'd love to see more people intentionally try to build and make things. . . . I wish more homeowners had a sense of agency and self-investment in how their houses are built and maintained. I think we'd move away from disposable solutions and cookie-cutter houses if we embraced this more as a culture.

The cookie cutter didn’t give up without a fight. The couple was repeatedly told by consultants and contractors – sadly, architects included - "most people don't do it like that." They’re happy living in what came of ignoring these words.

Because our home is typically our greatest expenditure in life, we treat it very conservatively. The biggest inhibition comes from fear that it won’t have resale value, so most of us live in houses designed more for phantom future inhabitants than for us. The perception that the next owner has a 1950s family serves a house-building industry financially interested in selling bigger houses. That perception is disproved by demographics. If you're an individual or couple without children at home, the biggest buyer pool looks just like you. Regardless, why not just design the house you’d like to live in yourself and enjoy your own life in it? On what will you spend the final resale income of an oversized house anyway? Thoreau had an idea for that, too: “. . . I reduce almost the whole advantage of holding this superfluous property as a fund in store against the future, so far as the individual is concerned, mainly to the defraying of funeral expenses.”

Less Dwelling, More Living

Lily Copenagle and Jamie Kennel designed their house with help from SketchUp, the free, user-friendly 3D program that's also used for Small House Lab's 3D models. It brings new visualization and experimentation powers to the masses, facilitating owner participation in house design. (Image courtesy Lily Copenagle.)

Two weeks ago, a New York Times story called "Freedom in 704 Square Feet" reported on an Oregon couple who built a small house in part to free their lives for other pursuits:

The idea was simple. They would create a home that was big enough for the two of them, but small enough so that it would be easy to maintain, environmentally responsible and inexpensive to operate. And that would allow them to free up their time and funds for intellectual and recreational pursuits. Own less, live more . . .

Small House Lab was conceived on faith that such people existed. On the eve of this site’s launch, their story brought confirmation that they do. The Times story then topped the paper's most-viewed-online list in the week that followed, signaling that the Oregon couple may not be outliers but forerunners of a new type of homeowner.

And why wouldn’t they be? They’re in the demographic mainstream of today’s America, where 55% of households are of one or two people, and only 20% are a couple with a child at home. Roll over, Ozzie and Harriet. Why care for an oversized house and work to pay it off when you could be reading, volunteering for your favorite cause or bike-touring Greece? It’s human to fixate on visible possessions and overlook invisible, more precious time, but at life’s end it’s the sum of our experiences, not our possessions, that will fill out the scorecard. As the one-room-cabin dweller Thoreau wrote in Walden:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when it came to die, discover that I had not lived.

Were Lily Copenagle and Jamie Kennel swayed by Thoreau when they built their 704 square foot house? I asked this and other questions by email, and heard back that they aren’t particularly influenced by any philosopher or writer, but do “try to live thoughtfully,” and “don't have a need to demonstrate social status through the accumulation and display of stuff.” They’re not out to make statement or repudiate a culture of materialism and excess. The couple seems instead to have pragmatically derived their house from qualities they liked in their previous homes.

Their first dwelling was an 1100 square foot loft. They liked its openness, but with the four dogs they had between them when they met, they needed outdoor space. The next stop was an 860 square foot, 1910 bungalow “arranged as a series of lots of little rooms, and we found that all six of us just moved from one little room to another,” according to Lily Copenagle. They also weren’t vitally occupying the whole house but using parts for storage. “We didn't like the idea of heating and furnishing rooms just because they were there, so we started thinking about what our ideal floor plan and size would look like.” They then looked for either a smaller house with a simple layout or a rare vacant city lot. They found a 700 square foot 1950s house at the north end of an oversized 50’ by 150’ lot. It was hopelessly moldy but the right size and looked south onto a gigantic back yard. They bought the house, tore it down and built a spatially luxurious, loft-like one-room house on its foundation. A wall of south-facing windows floods the new house with light and visually extends its space down the length of the yard. The one-story new house will allow the couple to age in place.

While their parents were approving and supportive, Lily's mother once joked that the couple took down a perfectly good two-bedroom house and put up a room. She may not have realized what an architectural compliment she was paying. In his 1954 book, The Natural House, Frank Lloyd Wright criticized houses like the couple's earlier 1911 bungalow:

The interiors consisted of boxes beside or inside boxes, called rooms. All boxes were inside a complicated outside boxing.

Even before that bungalow was built, Wright’s 1908 essay, In the Cause of Architecture, had argued:

A building should contain as few rooms as will meet the conditions which give it rise and under which the architect should strive continually to simplify . . .

Wright recalls the “simplify, simplify” of Thoreau, whose one-room cabin at Walden Pond took room reduction to the limit. If a building has only one room, all its vitality is concentrated in a single space. Such buildings may tap the psychological force of primal architecture, invoking archetypal cave and hut dwellings or ancient temples. To quote the architect Frank Gehry: “Think of the power of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings are one-room buildings.” These structures have a satisfying interior-exterior unity and irreducible simplicity. Masterpiece examples range from the Pantheon to Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. The latter, like Philip Johnson’s Glass House and other modern-house touchstones, is a single room, not counting bathrooms. Notably, these are only weekend houses. In Portland, Lily and Jamie have pushed the envelope by building a one-room primary residence. Their contentment in it may be less a proof of its viability for typical couples than a tribute to their exceptional relationship. Asked how they get by without interior doors, Lily emailed:

We still both work very long hours for our jobs, and we find that when we're home we are glad that we can be together, even if one of us is cooking and the other is working in the office area. We enjoy each other's company (and that of our dogs, of course) so much, and we seem to have so much overlap between the way we want to be in the space that we don't have the conflicts that other couples say they feel they would have. We also just really enjoy being kind to each other.

Their house may explore new territory in urban planning as well. American city neighborhoods are full of moldering, energy-inefficient wood-framed houses with the dated, box-like interior compartmentalization Wright mocked over a century ago. These neighborhoods retain valuable infrastructure, services, mixed-use community character and walkable density – qualities attractive to anyone disaffected with car-dependent suburban blandness. As the Portland couple has demonstrated, these neighborhoods also have reusable house foundations and utility hook-ups. It’s tempting to envision old neighborhoods as incubators of self-designed lives in owner-built houses, as fields awaiting a new crop. For the average person, building one’s own house typically involves buying land and having enough funds left over to qualify for a construction loan. This can be financially challenging for those shopping among typically large suburban lots, where zoning often dictates conventional tract-house forms and sizes. Urban tear-down sites may offer both affordability and creative freedom, along with sidewalks and community.

Demolition needn’t be wasteful. Lily and Jamie donated or reused material from the house they replaced, throwing away only one dumpster-load. Their replacement house is far more energy efficient.

Lily Copenagle and Jamie Kennel's floor plan organizes bathroom, storage and sleeping spaces into a support zone along one side and aligns the kitchen counter and a desk against the opposite side, leaving the space between as a well-defined living pavilion. Not shown is a freestanding storage unit that screens the bulk of the living space from the front door, at top, without diminishing the house's one-room appeal. The New York Times piece about the house has a slideshow with photos. (Image courtesy Lily Copenagle.)

Thoreau may not have inspired the Portland couple, but he’d surely approve. He built his cabin at Walden Pond with his own hands as deliberately as he created his life in the woods. Walden is largely a critique of the American home, which Thoreau sees as overinflated with “empty guest chambers for empty guests.” His take on the reason: “Most men appear never to have considered what a house is, and are actually though needlessly poor all their lives because they think that they must have such a one as their neighbors have.” In Thoreau’s accounting, the dwelling is inversely proportional to the living. He defines the cost of a house as “the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.” For this reason, “when the farmer has got his house, he may not be the richer but the poorer for it, and it may be the house that has got him.” As the man who wrote, “Our life is frittered away by detail,” Thoreau would have approved of this design requirement for the Portland house reported in the Times story: “Ms. Copenagle wanted a space that was small enough to vacuum completely in five minutes, within cord’s reach of a single outlet, so there wouldn’t have to be any unplugging and replugging of the vacuum cleaner.”

Of course, Thoreau’s managing to live in a tiny one-room cabin isn’t the point of Walden. The cabin is more important as a demonstration of personal instrumentality, of actively replacing received convention with a self-made, authentic life. This applies to the little house in Portland, too. As Lily emailed:

I think that one of the things that's interesting to me about the response to the article was that people seem to be relatively focused on the size, which is understandable, but what I wish other people were catching on to more was the extent to which we did this ourselves. . . . I'd love to see more people intentionally try to build and make things. . . . I wish more homeowners had a sense of agency and self-investment in how their houses are built and maintained. I think we'd move away from disposable solutions and cookie-cutter houses if we embraced this more as a culture.

The cookie cutter didn’t give up without a fight. The couple was repeatedly told by consultants and contractors – sadly, architects included - "most people don't do it like that." They’re happy living in what came of ignoring these words.

Because our home is typically our greatest expenditure in life, we treat it very conservatively. The biggest inhibition comes from fear that it won’t have resale value, so most of us live in houses designed more for phantom future inhabitants than for us. The perception that the next owner has a 1950s family serves a house-building industry financially interested in selling bigger houses. That perception is disproved by demographics. If you're an individual or couple without children at home, the biggest buyer pool looks just like you. Regardless, why not just design the house you’d like to live in yourself and enjoy your own life in it? On what will you spend the final resale income of an oversized house anyway? Thoreau had an idea for that, too: “. . . I reduce almost the whole advantage of holding this superfluous property as a fund in store against the future, so far as the individual is concerned, mainly to the defraying of funeral expenses.”