Architectural History

Detroit's Grand Central: Michigan Central Station

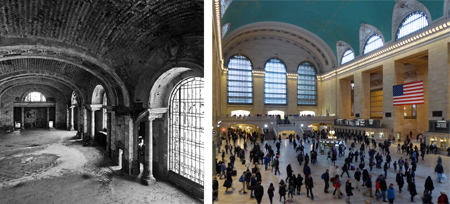

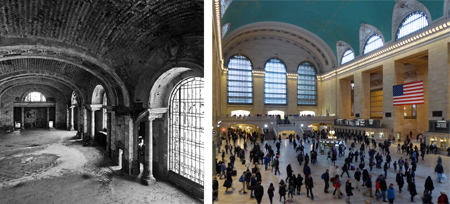

In its much-photographed desolation, Detroit's Michigan Central Station could be called America's Ruin, while New York's restored Grand Central Terminal more than ever lives up to its title as America's Piazza San Marco.

Grand Central was one of New York's first buildings to be targeted for landmark designation, sparing it from demolition to become one of the nation's most celebrated urban icons and the world's sixth-ranking tourist attraction. Michigan Central's listing on the National Register of Historic Places protects it only from federally-funded demolition. It has survived a 2009 appeal by Detroit's mayor for federal stimulus funds to pay for its removal and a City Council resolution that year calling on the Station's owner to demolish it with his own money. Michigan Central lacks the landmark designation that would give it the protection it deserves, including oversight of alterations or restoration. Political realities often drive preservation decisions and may explain how the Station remains unprotected.

The case for Michigan Central's landmark status seems obvious: America's preservation movement was born of the 1963 demolition of New York's Pennsylvania Station and proven in a battle for the preservation of Grand Central Terminal, Beaux-Arts train stations in the mold of Michigan Central.

Just how closely Michigan Central is related to Grand Central hasn't received due attention; it's often observed that they were designed by the same architects, but this only scratches the surface of their bond. The designers of both stations were a contentious team of two firms, Reed & Stem of St. Paul and Warren & Wetmore of New York. They were forced together by the New York Central Railroad, owner of the Michigan Central Railroad, in a shotgun-marriage of a partnership called the Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal, the name by which they also designed Michigan Central. The stations were their only large-scale collaborations and were designed almost at once for effectively the same client.

In its much-photographed desolation, Detroit's Michigan Central Station could be called America's Ruin, while New York's restored Grand Central Terminal more than ever lives up to its title as America's Piazza San Marco.

Grand Central was one of New York's first buildings to be targeted for landmark designation, sparing it from demolition to become one of the nation's most celebrated urban icons and the world's sixth-ranking tourist attraction. Michigan Central's listing on the National Register of Historic Places protects it only from federally-funded demolition. It has survived a 2009 appeal by Detroit's mayor for federal stimulus funds to pay for its removal and a City Council resolution that year calling on the Station's owner to demolish it with his own money. Michigan Central lacks the landmark designation that would give it the protection it deserves, including oversight of alterations or restoration. Political realities often drive preservation decisions and may explain how the Station remains unprotected.

The case for Michigan Central's landmark status seems obvious: America's preservation movement was born of the 1963 demolition of New York's Pennsylvania Station and proven in a battle for the preservation of Grand Central Terminal, Beaux-Arts train stations in the mold of Michigan Central.

Just how closely Michigan Central is related to Grand Central hasn't received due attention; it's often observed that they were designed by the same architects, but this only scratches the surface of their bond. The designers of both stations were a contentious team of two firms, Reed & Stem of St. Paul and Warren & Wetmore of New York. They were forced together by the New York Central Railroad, owner of the Michigan Central Railroad, in a shotgun-marriage of a partnership called the Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal, the name by which they also designed Michigan Central. The stations were their only large-scale collaborations and were designed almost at once for effectively the same client.

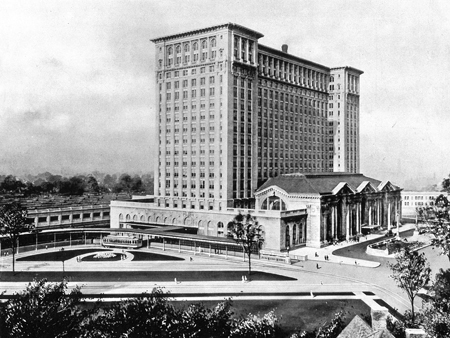

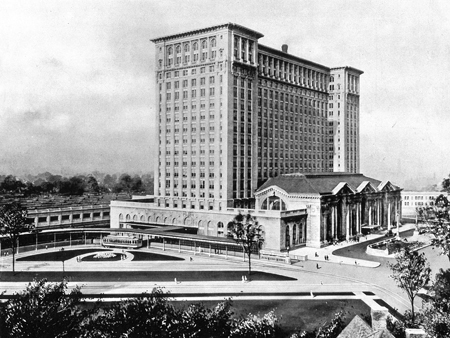

Renderings of Michigan Central Station with its defining tower (left) and Grand Central Terminal with its unbuilt one (right) show how similar they were in concept. Their trios of monumental arches, each flanked by paired columns and alternating with smaller openings, reveal a more specific level of similarity. Both opened in 1913; Grand Central in February and Michigan Central in December. Michigan Central's distinctive tower made it the world's tallest train station, and owes to the idea of one conceived for Grand Central. In both renderings, America's signature architectural innovation - the skyscraper - grows from a train station modeled on an ancient Roman bath. This duality reflects an underlying battle for the soul of American architecture then led by two Chicago architects: Louis Sullivan, "father of the skyscraper" and "prophet of modernism," and Daniel Burnham, the "father of the City Beautiful" who made classicism the era's national style. Beyond their juxtaposition of skyscraper and Roman bath, the stations are permeated by a mix of the historic and futuristic, giving them unique architectural depth.

Renderings of Michigan Central Station with its defining tower (left) and Grand Central Terminal with its unbuilt one (right) show how similar they were in concept. Their trios of monumental arches, each flanked by paired columns and alternating with smaller openings, reveal a more specific level of similarity. Both opened in 1913; Grand Central in February and Michigan Central in December. Michigan Central's distinctive tower made it the world's tallest train station, and owes to the idea of one conceived for Grand Central. In both renderings, America's signature architectural innovation - the skyscraper - grows from a train station modeled on an ancient Roman bath. This duality reflects an underlying battle for the soul of American architecture then led by two Chicago architects: Louis Sullivan, "father of the skyscraper" and "prophet of modernism," and Daniel Burnham, the "father of the City Beautiful" who made classicism the era's national style. Beyond their juxtaposition of skyscraper and Roman bath, the stations are permeated by a mix of the historic and futuristic, giving them unique architectural depth.

The shock of Michigan Central's abandoned grandeur distracts from its oddly conjoined building types and isolation from other large buildings. Grand Central is only the most immediate key to making sense of Detroit's Station. Its full explanation leads from ancient Rome through Paris and Chicago to New York at its most futuristic.

The shock of Michigan Central's abandoned grandeur distracts from its oddly conjoined building types and isolation from other large buildings. Grand Central is only the most immediate key to making sense of Detroit's Station. Its full explanation leads from ancient Rome through Paris and Chicago to New York at its most futuristic.

Richard Morris Hunt designed several houses for William K. Vanderbilt, including his 1892 Marble House in Newport (left). Hunt also designed the Administration Building (right) of Chicago's 1893 World's Fair, named the World's Columbian Exposition. The Fair popularized the classical architecture favored by Gilded Age tycoons like Vanderbilt and imprinted their taste on the American populace.

Vanderbilt was American aristocracy, the grandson of "Commodore" Cornelius Vanderbilt, founder of the New York Central Railroad. He was himself chairman of the Railroad's board of directors during the construction of Grand Central Terminal and Michigan Central Station, a time when railroads were a major part of the American economy. According to The Architecture of Warren & Wetmore by Peter Pennoyer and Anne Walker, "At the turn of the twentieth century, nearly two-fifths of the shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange were associated with railroads." The steel industry spawned by the rails themselves would help make America a superpower and provide the structural framework for the skyscrapers by which the world would know its cities.

Richard Morris Hunt was the first American architect to study at Paris's École des Beaux Arts, the centuries-old school which based education on classical precedents, giving its name to Beaux-Arts architecture. A generation of Americans followed Hunt's example in studying architecture at the École, often topping off their education with an internship at New York's most prominent architectural firm, McKim, Mead & White. These "Paris men" included Boring & Tilton, designers of Ellis Island's main building; Carrere & Hastings, architects of the New York Public Library; and Whitney Warren, of Warren & Wetmore, who set the architectural style for Grand Central and Michigan Central.

Richard Morris Hunt designed several houses for William K. Vanderbilt, including his 1892 Marble House in Newport (left). Hunt also designed the Administration Building (right) of Chicago's 1893 World's Fair, named the World's Columbian Exposition. The Fair popularized the classical architecture favored by Gilded Age tycoons like Vanderbilt and imprinted their taste on the American populace.

Vanderbilt was American aristocracy, the grandson of "Commodore" Cornelius Vanderbilt, founder of the New York Central Railroad. He was himself chairman of the Railroad's board of directors during the construction of Grand Central Terminal and Michigan Central Station, a time when railroads were a major part of the American economy. According to The Architecture of Warren & Wetmore by Peter Pennoyer and Anne Walker, "At the turn of the twentieth century, nearly two-fifths of the shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange were associated with railroads." The steel industry spawned by the rails themselves would help make America a superpower and provide the structural framework for the skyscrapers by which the world would know its cities.

Richard Morris Hunt was the first American architect to study at Paris's École des Beaux Arts, the centuries-old school which based education on classical precedents, giving its name to Beaux-Arts architecture. A generation of Americans followed Hunt's example in studying architecture at the École, often topping off their education with an internship at New York's most prominent architectural firm, McKim, Mead & White. These "Paris men" included Boring & Tilton, designers of Ellis Island's main building; Carrere & Hastings, architects of the New York Public Library; and Whitney Warren, of Warren & Wetmore, who set the architectural style for Grand Central and Michigan Central.

Students at the École des Beaux-Arts learned to build upon historic examples like Rome's Baths of Caracalla (above). While the school promoted rational analysis and planning which would pave the way for modernism, its adherence to classical forms and compositional rules can appear cult-like or even superstitious from a modern perspective. Classical precedents were viewed as pertinent educational models because they had been gradually refined over centuries. Whitney Warren defended their applicability to the New World:

Students at the École des Beaux-Arts learned to build upon historic examples like Rome's Baths of Caracalla (above). While the school promoted rational analysis and planning which would pave the way for modernism, its adherence to classical forms and compositional rules can appear cult-like or even superstitious from a modern perspective. Classical precedents were viewed as pertinent educational models because they had been gradually refined over centuries. Whitney Warren defended their applicability to the New World:

Architecture is always an evolution. Of course, we use old styles; we can't invent a new one, we can only evolve a new one. So we are taking the best elements in the old styles, and we are attempting to produce from them what is suggested and demanded by our present conditions - a new and American style.

Roman baths and basilicas were the ancient building types best suited as models for large buildings, including metropolitan train stations. The French architect and theorist Eugène Viollet-le-Duc published this conjectural reconstruction of Rome's Baths of Caracalla in his 1864 book, Discourses on Architecture. The arched windows at the top would admit light into the complex's lofty central hall beyond; they are the basis of classical architecture's half-round window element called the thermal window, after its use in Roman public baths, or thermae. In combination with the central hall's vaulted ceiling and triple-gable roof, thermal windows became an established Beaux-Arts building block which would become closely associated with train stations. The Baths' central archway and its flanking apses are the basis of another Beaux-Arts convention, prefiguring countless triple-arch façades in American cities. Implementing the Beaux-Art principle of outwardly expressed building organization, these portal trios would invariably indicate a grand interior space beyond, as they do at Grand Central Terminal and Michigan Central Station. The façade of Detroit's Station merges the gabled thermal window and triple archway motifs.

The French architect and theorist Eugène Viollet-le-Duc published this conjectural reconstruction of Rome's Baths of Caracalla in his 1864 book, Discourses on Architecture. The arched windows at the top would admit light into the complex's lofty central hall beyond; they are the basis of classical architecture's half-round window element called the thermal window, after its use in Roman public baths, or thermae. In combination with the central hall's vaulted ceiling and triple-gable roof, thermal windows became an established Beaux-Arts building block which would become closely associated with train stations. The Baths' central archway and its flanking apses are the basis of another Beaux-Arts convention, prefiguring countless triple-arch façades in American cities. Implementing the Beaux-Art principle of outwardly expressed building organization, these portal trios would invariably indicate a grand interior space beyond, as they do at Grand Central Terminal and Michigan Central Station. The façade of Detroit's Station merges the gabled thermal window and triple archway motifs.

The Baths of Caracalla, and perhaps Viollet-le-Duc's recreation specifically, inspired the architect Charles Atwood in his design of the Terminal Station for Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Popularly known as the White City, the Exposition was the largest world's fair to date. Most of its 27 million visitors arrived by rail, making Atwood's station the main portal to the fair's city-within-a-city and the epitome of the era's station-as-city-gate metaphor.

The Baths of Caracalla, and perhaps Viollet-le-Duc's recreation specifically, inspired the architect Charles Atwood in his design of the Terminal Station for Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Popularly known as the White City, the Exposition was the largest world's fair to date. Most of its 27 million visitors arrived by rail, making Atwood's station the main portal to the fair's city-within-a-city and the epitome of the era's station-as-city-gate metaphor.

The centerpiece of the White City was the Court of Honor, an arrangement of temporary classical buildings lining the Fair's Grand Basin, focused on Richard Morris Hunt's domed Administration Building. Atwood's Terminal Station (at upper left in the visitors' map above) stood squarely behind Hunt's centerpiece. The station's axial placement was in keeping with the Beaux-Arts emphasis on procession and gave it a prominence that may have owed to the role of E.T. Jeffery, General Manager of the Illinois Central Railroad, as chair of the Fair's Grounds and Buildings Committee. The Chicago architect Daniel Burnham headed the Fair's Architectural Commission, which favored the style of its contributing east-coast, École des Beaux-Arts-trained architects or their disciples. These men were exclusively responsible for the Court of Honor, where their shared classical language harmonized to a crowd-pleasing overall effect. The Court of Honor established a formula which would influence Grand Central Terminal, inform Michigan Central Station and endure into the 1930s with Rockefeller Center. The Fair's non-classical Transportation Building by Chicago's premier modernist, Louis Sullivan, was banished to a location off the Court of Honor. Burnham seemed to sell out his own city's progressive Chicago School, led by Sullivan, in favor of the consensus of classical architecture's rule book and of corporate fair sponsors who preferred the style, perhaps for its European pretension and imperial connotations. The architectural historian James Marston Fitch called the White City's classicism "the approved symbolism of Wall Street."

The centerpiece of the White City was the Court of Honor, an arrangement of temporary classical buildings lining the Fair's Grand Basin, focused on Richard Morris Hunt's domed Administration Building. Atwood's Terminal Station (at upper left in the visitors' map above) stood squarely behind Hunt's centerpiece. The station's axial placement was in keeping with the Beaux-Arts emphasis on procession and gave it a prominence that may have owed to the role of E.T. Jeffery, General Manager of the Illinois Central Railroad, as chair of the Fair's Grounds and Buildings Committee. The Chicago architect Daniel Burnham headed the Fair's Architectural Commission, which favored the style of its contributing east-coast, École des Beaux-Arts-trained architects or their disciples. These men were exclusively responsible for the Court of Honor, where their shared classical language harmonized to a crowd-pleasing overall effect. The Court of Honor established a formula which would influence Grand Central Terminal, inform Michigan Central Station and endure into the 1930s with Rockefeller Center. The Fair's non-classical Transportation Building by Chicago's premier modernist, Louis Sullivan, was banished to a location off the Court of Honor. Burnham seemed to sell out his own city's progressive Chicago School, led by Sullivan, in favor of the consensus of classical architecture's rule book and of corporate fair sponsors who preferred the style, perhaps for its European pretension and imperial connotations. The architectural historian James Marston Fitch called the White City's classicism "the approved symbolism of Wall Street."

In 1909, Daniel Burnham published his Plan of Chicago, based on the Beaux-Arts principles and axial planning so successfully previewed in the White City. It was co-authored by the architect and city planner Edward Bennett, edited by the journalist and historian Charles Moore, and compellingly illustrated with panoramic watercolors by the artist Jules Guerin. Although only partly implemented, the Plan of Chicago had a major influence on the new field of city planning. A few years after the book's publication, its authors and editor would turn their attention to Michigan Central Station.

Burnham was largely responsible for the historicism cloaking the technological advances of American architecture in the era of Grand Central and Michigan Central. Early in his career, he and his inventive partner John Wellborn Root designed progressive Chicago School buildings which boosted the city's reputation as a crucible of a new, distinctly American architecture. After Root's death in 1891, Burnham hired Charles Atwood to replace him as his firm's chief designer. Atwood was an adept classicist who had collaborated with Richard Morris Hunt on William K. Vanderbilt's Marble House. He would design more structures for the White City than any other architect, including its train station and the permanent building that now houses the Art Institute of Chicago. His tenure with Burnham lasted until 1895, when his job and then his increasingly skeletal presence went up in opium smoke. Burnham's and the nation's shift to classical dress would persist, arguably as a straight-jacket. In contributing historical designs to the White City, McKim, Mead & White helped fuel a demand for classicism that would force the firm to abandon the free-form American vernacular Shingle Style in which it had designed some of its best early buildings. A major architecture critic of the day, Montgomery Schuyler, wrote that the Fair's "success is first of all a success of unity, a triumph of ensemble. The whole is better than any of its parts and greater than all its parts, and its effect is one and indivisible." Schuyler noted that this was appropriate to a temporary fair, but not real architecture up to the demands of modern America. To Louis Sullivan, the Fair's unity was simplistic and limiting, imposing the orders of the tyrannical Old World's classical architecture at the expense of a free and natural expression appropriate to American democracy. He wrote that "the damage wrought by the World's Fair will last for half a century from its date, if not longer."

His protege Frank Lloyd Wright said of the American clientele converted to classical taste by the Fair, "They killed Sullivan and they nearly killed me!" In his Autobiography, Wright quotes Burnham laying down for him the new post-White City reality:

In 1909, Daniel Burnham published his Plan of Chicago, based on the Beaux-Arts principles and axial planning so successfully previewed in the White City. It was co-authored by the architect and city planner Edward Bennett, edited by the journalist and historian Charles Moore, and compellingly illustrated with panoramic watercolors by the artist Jules Guerin. Although only partly implemented, the Plan of Chicago had a major influence on the new field of city planning. A few years after the book's publication, its authors and editor would turn their attention to Michigan Central Station.

Burnham was largely responsible for the historicism cloaking the technological advances of American architecture in the era of Grand Central and Michigan Central. Early in his career, he and his inventive partner John Wellborn Root designed progressive Chicago School buildings which boosted the city's reputation as a crucible of a new, distinctly American architecture. After Root's death in 1891, Burnham hired Charles Atwood to replace him as his firm's chief designer. Atwood was an adept classicist who had collaborated with Richard Morris Hunt on William K. Vanderbilt's Marble House. He would design more structures for the White City than any other architect, including its train station and the permanent building that now houses the Art Institute of Chicago. His tenure with Burnham lasted until 1895, when his job and then his increasingly skeletal presence went up in opium smoke. Burnham's and the nation's shift to classical dress would persist, arguably as a straight-jacket. In contributing historical designs to the White City, McKim, Mead & White helped fuel a demand for classicism that would force the firm to abandon the free-form American vernacular Shingle Style in which it had designed some of its best early buildings. A major architecture critic of the day, Montgomery Schuyler, wrote that the Fair's "success is first of all a success of unity, a triumph of ensemble. The whole is better than any of its parts and greater than all its parts, and its effect is one and indivisible." Schuyler noted that this was appropriate to a temporary fair, but not real architecture up to the demands of modern America. To Louis Sullivan, the Fair's unity was simplistic and limiting, imposing the orders of the tyrannical Old World's classical architecture at the expense of a free and natural expression appropriate to American democracy. He wrote that "the damage wrought by the World's Fair will last for half a century from its date, if not longer."

His protege Frank Lloyd Wright said of the American clientele converted to classical taste by the Fair, "They killed Sullivan and they nearly killed me!" In his Autobiography, Wright quotes Burnham laying down for him the new post-White City reality:

The Fair is going to have a great influence in our country. The American people have seen the "Classics" on a grand scale for the first time. . . . I can see all America constructed along the lines of the Fair, in noble, dignified, Classic style. The great men of the day all feel that way about it - all of them.

Wright responded that Sullivan - Wright's "Lieber Meister" - didn't feel that way, and that Burnham's old partner Root wouldn't if he were still alive. Wright claimed the conversation took place as Burnham offered him an all-expenses-paid Beaux-Arts education in Paris and two years soaking up Rome, to be followed by a job with his firm. Wright declined and lived to portray Burnham as Mephistopheles and himself refusing to barter his self-reliant American soul, giving Ayn Rand material for the individualistic architect-protagonist Howard Roark in her novel, The Fountainhead. Ironically, it was Sullivan, not Burnham, who had attended the École des Beaux-Arts. In his Autobiography of an Idea, Sullivan wrote of leaving it with the "conviction that this Great School, in its perfect flower of technique, lacked the profound animus of a primal inspiration." He wrote that "beneath the law of the School lay a law which it ignored unsuspectingly or with fixed intention" which he "saw everywhere in the open of life." Sullivan institutionalized this law in his 1896 essay, "The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered":Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight, or the open apple-blossom, the toiling work-horse, the blithe swan, the branching oak, the winding stream at its base, the drifting clouds, over all the coursing sun, form ever follows function, and this is the law. Where function does not change, form does not change.

Sullivan had the last word: his "form follows function" is so ingrained in modern consciousness it's hard to believe architects only a century ago modeled train stations on Roman baths. Burnham's betting on the tycoons and their taste for classicism paid off. When he died in 1912 while touring Europe with his family, his firm was among the world's largest. The uncompromising Sullivan is now regarded as one of the three or four greatest architects in American history for his pioneering modernism, easily overshadowing Burnham, but he took the harder road to its bitter end. He died in obscurity in 1924, alone, alcoholic, months behind in rent on his cheap hotel-room home, his last office a couple of student-intern draftsmen in borrowed space. Burnham's White City gave impetus not only to Beaux-Arts architecture but ushered in the City Beautiful movement of the 1890s and early Twentieth Century, with its goal of improving the unwashed masses then swelling American cities. The Movement's proponents argued that architectural harmony, dignity, monumental grandeur and cohesive landscaping would inspire social order and civic virtue. Whitney Warren was a subscriber, stating his faith in "the moral effect of the cultivation of the aesthetic sense." Ellis Island, where Boring & Tilton's 1901 Beaux-Arts main building (above) adopted the thermal windows and triple-arch façade of the Baths of Caracalla, insured that this indoctrination began with the first American building immigrants entered. They would encounter reiterations of its edifying portal in the train stations of their destination cities and institutions like the New York Public Library and Detroit Institute of the Arts, where trios of arches marked passage into realms of culture and betterment. A poor excuse for social programs, the City Beautiful movement made great public relations for Beaux-Arts architects and helped justify huge expenditures on their projects.

Burnham's White City gave impetus not only to Beaux-Arts architecture but ushered in the City Beautiful movement of the 1890s and early Twentieth Century, with its goal of improving the unwashed masses then swelling American cities. The Movement's proponents argued that architectural harmony, dignity, monumental grandeur and cohesive landscaping would inspire social order and civic virtue. Whitney Warren was a subscriber, stating his faith in "the moral effect of the cultivation of the aesthetic sense." Ellis Island, where Boring & Tilton's 1901 Beaux-Arts main building (above) adopted the thermal windows and triple-arch façade of the Baths of Caracalla, insured that this indoctrination began with the first American building immigrants entered. They would encounter reiterations of its edifying portal in the train stations of their destination cities and institutions like the New York Public Library and Detroit Institute of the Arts, where trios of arches marked passage into realms of culture and betterment. A poor excuse for social programs, the City Beautiful movement made great public relations for Beaux-Arts architects and helped justify huge expenditures on their projects.

New York's Pennsylvania Station was one of the grandest American Beaux-Arts structures and exemplars of the City Beautiful movement. Designed by Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White for the Pennsylvania Railroad, its roof-line was dominated by the upper enclosure of its central waiting room, modeled on that of the central hall of the Baths of Caracalla. When the station opened in 1910, it was the world's fourth-largest building, the largest ever built at once, and a point of reference for all metropolitan stations to come. Penn Station was made possible by new electric train technology that allowed a rail tunnel under the Hudson River without the build-up of smoke that steam trains would have created. The Railroad's passengers from Pennsylvania and the West could continue straight into Manhattan by train, rather than having to transfer to Hudson River ferries on the New Jersey side. This would soon be paralleled by construction of the electrified train line under the Detroit River which gave rise to Michigan Central Station. Both Penn Station and Michigan Central were problematically tethered by river tunnels to locations well away from their cities' central business districts, where their presence failed to stimulate counted-upon development of more supportive surroundings.

New York's Pennsylvania Station was one of the grandest American Beaux-Arts structures and exemplars of the City Beautiful movement. Designed by Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White for the Pennsylvania Railroad, its roof-line was dominated by the upper enclosure of its central waiting room, modeled on that of the central hall of the Baths of Caracalla. When the station opened in 1910, it was the world's fourth-largest building, the largest ever built at once, and a point of reference for all metropolitan stations to come. Penn Station was made possible by new electric train technology that allowed a rail tunnel under the Hudson River without the build-up of smoke that steam trains would have created. The Railroad's passengers from Pennsylvania and the West could continue straight into Manhattan by train, rather than having to transfer to Hudson River ferries on the New Jersey side. This would soon be paralleled by construction of the electrified train line under the Detroit River which gave rise to Michigan Central Station. Both Penn Station and Michigan Central were problematically tethered by river tunnels to locations well away from their cities' central business districts, where their presence failed to stimulate counted-upon development of more supportive surroundings.

As noted in Construction News in 1913, Guillaume Abel Blouet's reconstruction drawing of the central hall of the Baths of Caracalla, published in 1828, prefigures Charles McKim's even larger waiting room at Penn Station. According to his friend and biographer Charles Moore, McKim was fascinated by the Baths' ruins on a trip to Rome they made in 1901, going so far as to hire "willing but astonished workmen to pose among the ruins to give scale and movement" as he sketched the scene, apparently for future reference in his own work. His firm's involvement with the White City would have familiarized him with Atwood's Terminal Station modeled on the Baths, and his Rome sketches would naturally have come to hand when he received the commission for Pennsylvania Station, where vast numbers of citizens would converge as Romans had in their great bath complexes. The Pennsylvania Railroad at first planned a hotel tower above Penn Station to generate revenue offsetting its cost. No fan of newfangled skyscrapers, McKim convinced the Railroad's president, Alexander Cassatt, that a tower would compromise the integrity of a building modeled on an ancient archetype.

As noted in Construction News in 1913, Guillaume Abel Blouet's reconstruction drawing of the central hall of the Baths of Caracalla, published in 1828, prefigures Charles McKim's even larger waiting room at Penn Station. According to his friend and biographer Charles Moore, McKim was fascinated by the Baths' ruins on a trip to Rome they made in 1901, going so far as to hire "willing but astonished workmen to pose among the ruins to give scale and movement" as he sketched the scene, apparently for future reference in his own work. His firm's involvement with the White City would have familiarized him with Atwood's Terminal Station modeled on the Baths, and his Rome sketches would naturally have come to hand when he received the commission for Pennsylvania Station, where vast numbers of citizens would converge as Romans had in their great bath complexes. The Pennsylvania Railroad at first planned a hotel tower above Penn Station to generate revenue offsetting its cost. No fan of newfangled skyscrapers, McKim convinced the Railroad's president, Alexander Cassatt, that a tower would compromise the integrity of a building modeled on an ancient archetype.

The New York Central Railroad's brilliant chief engineer William Wilgus exploited the electrification of trains that made Penn Station possible in his own plans for Grand Central Terminal and Michigan Central Station. Wilgus's formal education went no further than Buffalo Central High School. Unable to afford college, he apprenticed to a civil engineer for two years and took a correspondence course in drafting. By 34, his native, practical genius had made him Chief Engineer of the entire New York Central Railroad.

Wilgus seized on the opportunity electrification presented to build a train tunnel under the Detroit River, shortening routes from the East to Detroit and Chicago. He personally developed new technology for laying the tunnel that was Michigan Central Station's reason for being. Detroit's Station would share much of his innovative planning for Grand Central.

The New York Central Railroad's brilliant chief engineer William Wilgus exploited the electrification of trains that made Penn Station possible in his own plans for Grand Central Terminal and Michigan Central Station. Wilgus's formal education went no further than Buffalo Central High School. Unable to afford college, he apprenticed to a civil engineer for two years and took a correspondence course in drafting. By 34, his native, practical genius had made him Chief Engineer of the entire New York Central Railroad.

Wilgus seized on the opportunity electrification presented to build a train tunnel under the Detroit River, shortening routes from the East to Detroit and Chicago. He personally developed new technology for laying the tunnel that was Michigan Central Station's reason for being. Detroit's Station would share much of his innovative planning for Grand Central.

The New York Central's train yard for its 42nd Street depot was at first north of populated areas. Smoke-belching steam trains required a single-level, open-air rail yard. With New York expanding around the yard, noise and pollution from steam engines prompted the city to ban them even as growing ridership demanded a larger station and more tracks.

The New York Central's train yard for its 42nd Street depot was at first north of populated areas. Smoke-belching steam trains required a single-level, open-air rail yard. With New York expanding around the yard, noise and pollution from steam engines prompted the city to ban them even as growing ridership demanded a larger station and more tracks.

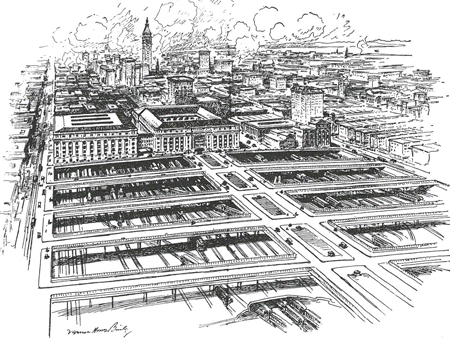

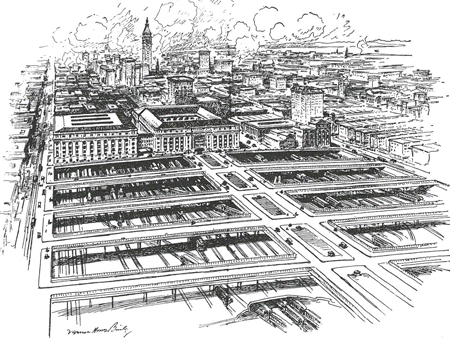

Wilgus saw that electric trains could allow the station's approaching tracks to be stacked two-high and covered with streets and buildings. He conceived a plan by which the cost of electrification and new infrastructure would be paid out of revenue from development of the buildings above, within the Railroad's "air rights." The 1903 illustration above from Scientific American shows Wilgus's vision, called Terminal City, awaiting construction of blocks of buildings above the tracks, with the existing Grand Central Depot remaining in the background.

Wilgus saw that electric trains could allow the station's approaching tracks to be stacked two-high and covered with streets and buildings. He conceived a plan by which the cost of electrification and new infrastructure would be paid out of revenue from development of the buildings above, within the Railroad's "air rights." The 1903 illustration above from Scientific American shows Wilgus's vision, called Terminal City, awaiting construction of blocks of buildings above the tracks, with the existing Grand Central Depot remaining in the background.

When Harper's Weekly published this updated vision of Terminal City in 1907, Park Avenue's mall was added, on axis with a new classical terminal. These developments showed the influence of the City Beautiful movement.

When Harper's Weekly published this updated vision of Terminal City in 1907, Park Avenue's mall was added, on axis with a new classical terminal. These developments showed the influence of the City Beautiful movement.

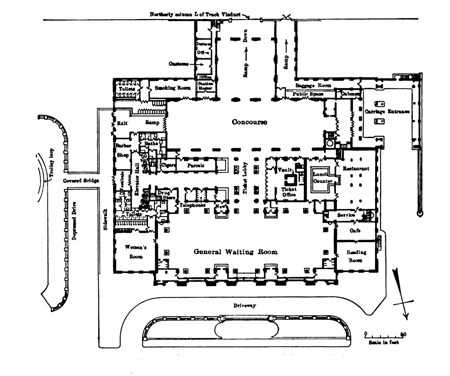

In 1903, a competition was held to select an architect for Grand Central Terminal. Reed & Stem won with the design entry above, besting far more prominent competitors McKim, Mead & White and Daniel Burnham. It didn't hurt that Charles Reed was William Wilgus's brother-in-law and benefitted from privileged conversations with him, although Reed & Stem brought legitimate railroad station experience and an ingenuity that would contribute to Grand Central's greatness. The choice of the firm put the thinnest possible architectural glove on Wilgus's controlling hand. Reed & Stem executed a design agenda he had proposed to the Railroad before the competition, in 1902, which included a revenue-generating office tower above the new Terminal, elevated roadways to carry Park Avenue traffic around it, a system of ramps to move large volumes of foot traffic through it, and a grand court over the train yard north of the Terminal. Despite its White City-based grand court, Wilgus's wildly imaginative and comprehensive mixed-use vision was perhaps the Twentieth Century's greatest single act of architectural invention. Reed & Stem's competition entry fleshed out Wilgus's outline, placing the Terminal and its tower at the head of a grand mall flanked by classical buildings meant to house the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Academy of Design, which would be built over the Railroad's train yard. This mall was derivative of the White City's Court of Honor to the point of being called the "Court of Honor." A poor fit for Manhattan's implacable street grid, Reed & Stem's plan concept did not survive the further development of Grand Central's design, but it would re-emerge as the basis of Michigan Central's.

In 1903, a competition was held to select an architect for Grand Central Terminal. Reed & Stem won with the design entry above, besting far more prominent competitors McKim, Mead & White and Daniel Burnham. It didn't hurt that Charles Reed was William Wilgus's brother-in-law and benefitted from privileged conversations with him, although Reed & Stem brought legitimate railroad station experience and an ingenuity that would contribute to Grand Central's greatness. The choice of the firm put the thinnest possible architectural glove on Wilgus's controlling hand. Reed & Stem executed a design agenda he had proposed to the Railroad before the competition, in 1902, which included a revenue-generating office tower above the new Terminal, elevated roadways to carry Park Avenue traffic around it, a system of ramps to move large volumes of foot traffic through it, and a grand court over the train yard north of the Terminal. Despite its White City-based grand court, Wilgus's wildly imaginative and comprehensive mixed-use vision was perhaps the Twentieth Century's greatest single act of architectural invention. Reed & Stem's competition entry fleshed out Wilgus's outline, placing the Terminal and its tower at the head of a grand mall flanked by classical buildings meant to house the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Academy of Design, which would be built over the Railroad's train yard. This mall was derivative of the White City's Court of Honor to the point of being called the "Court of Honor." A poor fit for Manhattan's implacable street grid, Reed & Stem's plan concept did not survive the further development of Grand Central's design, but it would re-emerge as the basis of Michigan Central's.

Daniel Burnham's Grand Central competition entry doesn't survive. It was defeated by Reed & Stem's entry, featuring a less liquid version of his White City's Court of Honor, above.

Daniel Burnham's Grand Central competition entry doesn't survive. It was defeated by Reed & Stem's entry, featuring a less liquid version of his White City's Court of Honor, above.

When Roosevelt Park was completed in 1922, its mall approaching Michigan Central Station strongly recalled Reed & Stem's competition scheme for Grand Central. One can almost see its classical side-buildings willing themselves into being on either side of the mall to complete the Court of Honor ensemble. In 1910, three years before the Station's opening, the Railroad had proposed that the city "buy some adjacent property and improve it for park purposes so that persons entering the city may at once have a favorable impression of Detroit." The next year, the City Plan and Improvement Commission announced Detroit's intention to acquire the land in front of the station to create a suitable approach to it. The Commission was headed by the same Charles Moore who had watched Charles McKim sketch hired extras at the Baths of Caracalla and edited Burnham and Bennett's Plan of Chicago. A native of nearby Ypsilanti, Michigan, Moore also helped create Washington's McMillan Commission - made up of White City alumna including Burnham and McKim - to expand on L'Enfant's original Capital master plan along City Beautiful lines. Moore's Detroit Commission hired Burnham and Bennett as consultants for what would become Roosevelt Park in February of 1912, bringing Reed & Stem's Court of Honor solution full circle with the formula's originator. Bennett completed the project after Burnham's death four months later.

Where the park's mall now stands, a 200-foot wide boulevard was first proposed, in one version extending to Woodward Avenue's then-proposed Art Center which would come to include Detroit's Main Library and Institute of Arts, Beaux-Arts, City Beautiful monuments. The boulevard idea gave way to plans for Roosevelt Park under pressure from the City Council, but the plots of parkland on either side of its mall might as well be placeholders for Court of Honor buildings to come. This could explain the city's displacement of blocks of homes and businesses, and investment of $700,000, or about $100 million today, for the park. Detroit appears to have bought into speculation by the Railroad that Michigan Central would spark development which would close ranks with the station and make its tower a money-maker and architectural focus rather than an outlier. The complementary Beaux-Arts character of the buildings that would complete the ensemble would never have been in doubt, as the official future of the time was Burnham's vision of "all America constructed along the lines of the Fair, in noble, dignified, Classic style." This if-you-build-it-they-will-come faith would have subscribed to Burnham's famous maxim:

When Roosevelt Park was completed in 1922, its mall approaching Michigan Central Station strongly recalled Reed & Stem's competition scheme for Grand Central. One can almost see its classical side-buildings willing themselves into being on either side of the mall to complete the Court of Honor ensemble. In 1910, three years before the Station's opening, the Railroad had proposed that the city "buy some adjacent property and improve it for park purposes so that persons entering the city may at once have a favorable impression of Detroit." The next year, the City Plan and Improvement Commission announced Detroit's intention to acquire the land in front of the station to create a suitable approach to it. The Commission was headed by the same Charles Moore who had watched Charles McKim sketch hired extras at the Baths of Caracalla and edited Burnham and Bennett's Plan of Chicago. A native of nearby Ypsilanti, Michigan, Moore also helped create Washington's McMillan Commission - made up of White City alumna including Burnham and McKim - to expand on L'Enfant's original Capital master plan along City Beautiful lines. Moore's Detroit Commission hired Burnham and Bennett as consultants for what would become Roosevelt Park in February of 1912, bringing Reed & Stem's Court of Honor solution full circle with the formula's originator. Bennett completed the project after Burnham's death four months later.

Where the park's mall now stands, a 200-foot wide boulevard was first proposed, in one version extending to Woodward Avenue's then-proposed Art Center which would come to include Detroit's Main Library and Institute of Arts, Beaux-Arts, City Beautiful monuments. The boulevard idea gave way to plans for Roosevelt Park under pressure from the City Council, but the plots of parkland on either side of its mall might as well be placeholders for Court of Honor buildings to come. This could explain the city's displacement of blocks of homes and businesses, and investment of $700,000, or about $100 million today, for the park. Detroit appears to have bought into speculation by the Railroad that Michigan Central would spark development which would close ranks with the station and make its tower a money-maker and architectural focus rather than an outlier. The complementary Beaux-Arts character of the buildings that would complete the ensemble would never have been in doubt, as the official future of the time was Burnham's vision of "all America constructed along the lines of the Fair, in noble, dignified, Classic style." This if-you-build-it-they-will-come faith would have subscribed to Burnham's famous maxim:

Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably will not themselves be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die.

Daylight showing through the still-unfinished and unrented floors of Michigan Central's tower in photos taken after the Park's completion is a troubling sign that no one would be coming to the party, regardless of its plans or diagram. From today's defeatist attitude toward grand projects, the audacity and optimism on display at Michigan Central is - for all its hubris - impressive. William Wilgus wasn't the only New York Central executive with an architect in the family. His boss, William K. Vanderbilt, was a close friend and cousin of the architect Whitney Warren, pictured above on Vanderbilt's yacht, Tarantula. The society architect responsible for the New York Yacht Club's fanciful galleon windows, Warren was of a different world altogether from Wilgus or Reed's. MIT may have been a good enough school for a proletarian railroad architect like Reed, but Warren's ambitions had him spend his entire twenties touring Europe and attending the École des Beaux-Arts. He then worked for McKim, Mead & White before starting his own practice and taking on a wealthy client, the lawyer Charles Wetmore, as his business partner. Warren could see what a huge impact Grand Central Terminal would have on the face of New York and lobbied his cousin to become its architect, even though Reed & Stem had already competed for and won the job. Vanderbilt acceded, forcing Reed & Stem into partnership with Warren & Wetmore as the Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal. Wilgus would hardly have been in a position to complain, given the taint of nepotism on his brother-in-law's competition win. The selection of a compliant Reed & Stem had secured the execution of his original vision, keeping at bay the meddling of higher-profile competitors with bigger egos. He can't have been happy seeing Warren & Wetmore come aboard. For Vanderbilt, Warren's involvement would assure that his business projected the same level of Beaux-Arts connoisseurship as his homes.

From the start, Whitney Warren challenged fundamentals of Reed & Stem's design - and Wilgus's underlying concept - including its ramps, elevated roadway and especially its office tower. When Charles Reed died in 1911, Warren's partner Charles Wetmore arranged a new contract cutting Reed & Stem out of involvement in Grand Central altogether. In Godfatheresque style, the deal was hatched by Wetmore and Railroad President William Newman on their train ride back to New York from Reed's funeral. There was rancor in its terms, by which Reed & Stem would be denied payment and credit for work done. The effort was blocked by a lawsuit from Reed's estate and his partner Allen Stem. Warren & Wetmore were forced to pay damages and Whitney Warren bore the humiliation of expulsion from the American Institute of Architects for breaching its code of professional conduct. None of this made a good case for "the moral effect of the cultivation of the aesthetic sense," and in Wilgus's eyes was just another example of "the moral turpitude which marked the course of Warren & Wetmore in their entire relation to the Grand Central Station architecture."

Despite the collaborating architects' animosity, a hugely successful project was completed. Differences in design direction were settled by formidable Railroad board members. In New York, these included J.P. Morgan, William Rockefeller and Lewis Cass Ledyard. Ledyard sat on the boards of both the New York Central Railroad and its minority partner, the New Haven Railroad, and was instrumental in retaining the elevated Park Avenue roadway around the Terminal. His brother, Henry Brockholst Ledyard, was chairman of the Michigan Central Railroad's board and would have guided decisions on Michigan Central Station. Their grandfather had been a Michigan senator, their father a mayor of Detroit. In New York, the board members voted against building Grand Central with a tower, but in favor of including structural capacity to support one in the future. In Detroit, station and tower would be built at once.

William Wilgus wasn't the only New York Central executive with an architect in the family. His boss, William K. Vanderbilt, was a close friend and cousin of the architect Whitney Warren, pictured above on Vanderbilt's yacht, Tarantula. The society architect responsible for the New York Yacht Club's fanciful galleon windows, Warren was of a different world altogether from Wilgus or Reed's. MIT may have been a good enough school for a proletarian railroad architect like Reed, but Warren's ambitions had him spend his entire twenties touring Europe and attending the École des Beaux-Arts. He then worked for McKim, Mead & White before starting his own practice and taking on a wealthy client, the lawyer Charles Wetmore, as his business partner. Warren could see what a huge impact Grand Central Terminal would have on the face of New York and lobbied his cousin to become its architect, even though Reed & Stem had already competed for and won the job. Vanderbilt acceded, forcing Reed & Stem into partnership with Warren & Wetmore as the Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal. Wilgus would hardly have been in a position to complain, given the taint of nepotism on his brother-in-law's competition win. The selection of a compliant Reed & Stem had secured the execution of his original vision, keeping at bay the meddling of higher-profile competitors with bigger egos. He can't have been happy seeing Warren & Wetmore come aboard. For Vanderbilt, Warren's involvement would assure that his business projected the same level of Beaux-Arts connoisseurship as his homes.

From the start, Whitney Warren challenged fundamentals of Reed & Stem's design - and Wilgus's underlying concept - including its ramps, elevated roadway and especially its office tower. When Charles Reed died in 1911, Warren's partner Charles Wetmore arranged a new contract cutting Reed & Stem out of involvement in Grand Central altogether. In Godfatheresque style, the deal was hatched by Wetmore and Railroad President William Newman on their train ride back to New York from Reed's funeral. There was rancor in its terms, by which Reed & Stem would be denied payment and credit for work done. The effort was blocked by a lawsuit from Reed's estate and his partner Allen Stem. Warren & Wetmore were forced to pay damages and Whitney Warren bore the humiliation of expulsion from the American Institute of Architects for breaching its code of professional conduct. None of this made a good case for "the moral effect of the cultivation of the aesthetic sense," and in Wilgus's eyes was just another example of "the moral turpitude which marked the course of Warren & Wetmore in their entire relation to the Grand Central Station architecture."

Despite the collaborating architects' animosity, a hugely successful project was completed. Differences in design direction were settled by formidable Railroad board members. In New York, these included J.P. Morgan, William Rockefeller and Lewis Cass Ledyard. Ledyard sat on the boards of both the New York Central Railroad and its minority partner, the New Haven Railroad, and was instrumental in retaining the elevated Park Avenue roadway around the Terminal. His brother, Henry Brockholst Ledyard, was chairman of the Michigan Central Railroad's board and would have guided decisions on Michigan Central Station. Their grandfather had been a Michigan senator, their father a mayor of Detroit. In New York, the board members voted against building Grand Central with a tower, but in favor of including structural capacity to support one in the future. In Detroit, station and tower would be built at once.

On the opposite side of the Court of Honor in Reed & Stem's winning competition entry, Grand Central's south face would have been weakly expressed by a flush colonnade and subsumed into the office tower above it. The decision to treat this side as the rear façade may have been driven by the complicating viaduct, seen at right, and elevated roadway diverting Park Avenue around the Terminal, conceived by Wilgus.

On the opposite side of the Court of Honor in Reed & Stem's winning competition entry, Grand Central's south face would have been weakly expressed by a flush colonnade and subsumed into the office tower above it. The decision to treat this side as the rear façade may have been driven by the complicating viaduct, seen at right, and elevated roadway diverting Park Avenue around the Terminal, conceived by Wilgus.

Whitney Warren's 1910 reworking of the Terminal dispensed with the office tower altogether, made its south face its main public façade, and removed the Park Avenue viaduct and raised roadway, allowing for a properly formal center entrance. This turned the Terminal around to face not only the established city and main thoroughfare of 42nd Street, but the sun, allowing the play of light and shadow its main façade's classically molded features were made for. Warren gave his sketch's triple arch motif a rationale rooted, like his education, in the classical past:

Whitney Warren's 1910 reworking of the Terminal dispensed with the office tower altogether, made its south face its main public façade, and removed the Park Avenue viaduct and raised roadway, allowing for a properly formal center entrance. This turned the Terminal around to face not only the established city and main thoroughfare of 42nd Street, but the sun, allowing the play of light and shadow its main façade's classically molded features were made for. Warren gave his sketch's triple arch motif a rationale rooted, like his education, in the classical past:

In ancient times the entrance to the city was through an opening in the walls or fortifications. This portal was usually decorated and elaborated into an Arc of Triumph, erected to some military or naval victory, or to the glory of some great personage. The city of today has no wall surrounding that may serve, by elaboration, as a pretext to such glorification, but none the less the gateway must exist, and in the case of New York and other cities it is through a tunnel which discharges the human flow in the very centre of the town.

Warren's reference to "other cities" applies his portal reasoning to Detroit and the heroic arches of his design for Michigan Central. In Warren & Wetmore's developed Grand Central façade drawing, the Terminal still faces south, but the elevated roadway around it and the Park Avenue viaduct have been restored. Warren's handwritten notes on the drawing show him raiding his own oeuvre for parts, a common practice for busy architects. The note at top left reads, “put on soffit decorated as in post office building,” referring to an earlier Terminal City building of his design. While neither the coffered post office soffit nor the recessed panels Whitney freehanded onto this drafted elevation drawing were adopted for the façade - to the good of its simple force - elements of Terminal City would be shared with Michigan Central Station.

In Warren & Wetmore's developed Grand Central façade drawing, the Terminal still faces south, but the elevated roadway around it and the Park Avenue viaduct have been restored. Warren's handwritten notes on the drawing show him raiding his own oeuvre for parts, a common practice for busy architects. The note at top left reads, “put on soffit decorated as in post office building,” referring to an earlier Terminal City building of his design. While neither the coffered post office soffit nor the recessed panels Whitney freehanded onto this drafted elevation drawing were adopted for the façade - to the good of its simple force - elements of Terminal City would be shared with Michigan Central Station.

Whitney Warren's fingerprints are on the coffered archways of both Grand Central's main concourse and Michigan Central's waiting room. In addition to their similar chandeliers and benches, the stations both have interior wall coverings of artificial Caen stone above a marble wainscot. The Guastavino tile vaults of Michigan Central's waiting room also famously form the ceiling of Grand Central's Oyster Bar. The Spanish-immigrant architect Rafael Guastavino developed traditional Catalan vaulting into this structurally innovative system, which combines beauty with self-supporting strength. Guastavino vaults are a particular grace note of American Beaux-Arts architecture. At Michigan Central, they stand in for Grand Central's turquoise celestial ceiling. On a par with the Guastavino vaulted ceiling of Ellis Island's Great Hall, Michigan Central's is one of the more impressive ever built. It appears heroically intact in ruin photos.

Whitney Warren's fingerprints are on the coffered archways of both Grand Central's main concourse and Michigan Central's waiting room. In addition to their similar chandeliers and benches, the stations both have interior wall coverings of artificial Caen stone above a marble wainscot. The Guastavino tile vaults of Michigan Central's waiting room also famously form the ceiling of Grand Central's Oyster Bar. The Spanish-immigrant architect Rafael Guastavino developed traditional Catalan vaulting into this structurally innovative system, which combines beauty with self-supporting strength. Guastavino vaults are a particular grace note of American Beaux-Arts architecture. At Michigan Central, they stand in for Grand Central's turquoise celestial ceiling. On a par with the Guastavino vaulted ceiling of Ellis Island's Great Hall, Michigan Central's is one of the more impressive ever built. It appears heroically intact in ruin photos.

A rendering published in the April, 1911, issue of Munsey's Magazine shows "the new Grand Central Station, with the great office-building which is ultimately to be erected over the Concourses," reflecting the 1909 decision by the Railroad's board to defer construction of the tower. In placing the future skyscraper above the Terminal's stacked main and suburban concourses, Whitney Warren ensured that the waiting room would project forward under its own roof and signify the entire station, just as in his design for Michigan Central, and as Reed & Stem had done on the Court of Honor side of their Terminal design. Like his old employer Charles McKim at Penn Station, Warren would have objected to the dissonance of a modern skyscraper rising from a classical monument. One senses Warren, his hand forced, half-heartedly cutting and pasting Reed & Stem's blocky competition-entry skyscraper with its mansard roof onto his self-contained station rather than making the tower his own. The awkward result would only make his case that the skyscraper didn't belong. The tower was all Wilgus, a sail raised to catch money and drive the financial side of his grand plan, no skin off his Beaux-Arts-uneducated nose. The idea of skyscraper-as-financial-motor couldn't have been more current. Cass Gilbert, architect of New York's Woolworth Building - the world's tallest skyscraper when it opened in the same year as Grand Central and Michigan Central - famously called the skyscraper "a machine that makes the land pay."

A rendering published in the April, 1911, issue of Munsey's Magazine shows "the new Grand Central Station, with the great office-building which is ultimately to be erected over the Concourses," reflecting the 1909 decision by the Railroad's board to defer construction of the tower. In placing the future skyscraper above the Terminal's stacked main and suburban concourses, Whitney Warren ensured that the waiting room would project forward under its own roof and signify the entire station, just as in his design for Michigan Central, and as Reed & Stem had done on the Court of Honor side of their Terminal design. Like his old employer Charles McKim at Penn Station, Warren would have objected to the dissonance of a modern skyscraper rising from a classical monument. One senses Warren, his hand forced, half-heartedly cutting and pasting Reed & Stem's blocky competition-entry skyscraper with its mansard roof onto his self-contained station rather than making the tower his own. The awkward result would only make his case that the skyscraper didn't belong. The tower was all Wilgus, a sail raised to catch money and drive the financial side of his grand plan, no skin off his Beaux-Arts-uneducated nose. The idea of skyscraper-as-financial-motor couldn't have been more current. Cass Gilbert, architect of New York's Woolworth Building - the world's tallest skyscraper when it opened in the same year as Grand Central and Michigan Central - famously called the skyscraper "a machine that makes the land pay."

In Detroit, the Railroad lacked the luxury of a large swath of already-owned land. Its new business model of building speculative real estate over its property appears to have had no other financially feasible outlet than a tower directly over the station. Apparently resigned to this, Warren made an honest effort to integrate them. The projecting waiting room expresses the entire station, the rest of which is contained in the one-story podium from which the tower rises. In contrast to Warren's visually detachable tower in the Grand Central rendering, Michigan Central's formal components interlock, and the tower is clearly Warren's. Architectural Record wasn't impressed, complaining that tower and station were "architecturally incongruous" and objecting that the casual observer "would never take the two parts of the station to be portions of one and the same building." This criticism not only failed to acknowledge Warren's challenge and achievement, but missed the bigger story that Michigan Central, child of the White City and Terminal City, was a new creature which had outgrown single-building ambitions and was operating at the scale of the sub-city.

In Detroit, the Railroad lacked the luxury of a large swath of already-owned land. Its new business model of building speculative real estate over its property appears to have had no other financially feasible outlet than a tower directly over the station. Apparently resigned to this, Warren made an honest effort to integrate them. The projecting waiting room expresses the entire station, the rest of which is contained in the one-story podium from which the tower rises. In contrast to Warren's visually detachable tower in the Grand Central rendering, Michigan Central's formal components interlock, and the tower is clearly Warren's. Architectural Record wasn't impressed, complaining that tower and station were "architecturally incongruous" and objecting that the casual observer "would never take the two parts of the station to be portions of one and the same building." This criticism not only failed to acknowledge Warren's challenge and achievement, but missed the bigger story that Michigan Central, child of the White City and Terminal City, was a new creature which had outgrown single-building ambitions and was operating at the scale of the sub-city.

While Warren & Wetmore's Biltmore Hotel tower, at left above, was built across Vanderbilt Avenue from Grand Central, it was in a way built over it; the Terminal's platform levels extend below the Avenue and formed part of the hotel's basement. Passengers on arriving trains could take elevators from the Terminal's Incoming Station Waiting Room directly up into the hotel, their baggage carried from train to hotel room by the Biltmore's porters.

While Warren & Wetmore's Biltmore Hotel tower, at left above, was built across Vanderbilt Avenue from Grand Central, it was in a way built over it; the Terminal's platform levels extend below the Avenue and formed part of the hotel's basement. Passengers on arriving trains could take elevators from the Terminal's Incoming Station Waiting Room directly up into the hotel, their baggage carried from train to hotel room by the Biltmore's porters.

The Biltmore and its underground connection to Grand Central are seen at lower left in these Terminal City section drawings. Even this detail of Terminal City dates from Wilgus's original vision, which included a luxury hotel so located and linked.

Both Michigan Central Station and Grand Central Terminal have been called predecessors of the megastructure, a term the architect Fumihiko Maki defined as "a large frame in which all the functions of a city or part of a city are housed." From their earliest ancestors, like Florence's Ponte Vecchio with its saddlebag dwellings and shops, megastructures have been built on transportation systems. The architectural historian Reyner Banham illustrated his 1976 book, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, with these same Terminal City section drawings, and captioned them:

The Biltmore and its underground connection to Grand Central are seen at lower left in these Terminal City section drawings. Even this detail of Terminal City dates from Wilgus's original vision, which included a luxury hotel so located and linked.

Both Michigan Central Station and Grand Central Terminal have been called predecessors of the megastructure, a term the architect Fumihiko Maki defined as "a large frame in which all the functions of a city or part of a city are housed." From their earliest ancestors, like Florence's Ponte Vecchio with its saddlebag dwellings and shops, megastructures have been built on transportation systems. The architectural historian Reyner Banham illustrated his 1976 book, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, with these same Terminal City section drawings, and captioned them:

A memorable complex of interconnected concourses, hotels, office accommodation, shopping and railway facilities straddling two levels of tracks and interlaced with roads. Grand Central . . . is often cited by New Yorkers as proof that megastructure was invented in that city.

An anecdote from Grand Central: Gateway to a Million Lives by John Belle and Maxinne R. Leighton makes its own case that Grand Central is a megastructure:The Hotel Biltmore was located directly above the Terminal's arrival tracks, so that it was possible for a person to book a room at the Biltmore, arrive at Grand Central, and take an elevator from the concourse level or walk up a short flight of stairs from the Incoming Train Station Waiting Room to the hotel lobby without going outside. In the 1940s a honeymooning couple had arrived at the Terminal to take a train to Niagara Falls when a violent storm struck the city, disrupting all service. The couple took a room in the Biltmore, had their meals at the Oyster Bar, shopped in the Terminal's stores, and spent the weekend without once venturing out into the hostile weather.

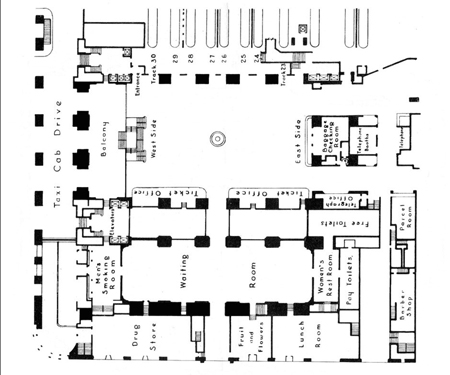

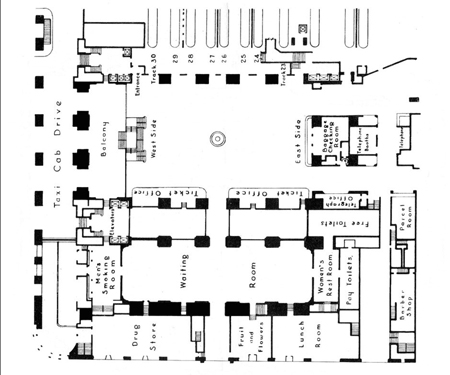

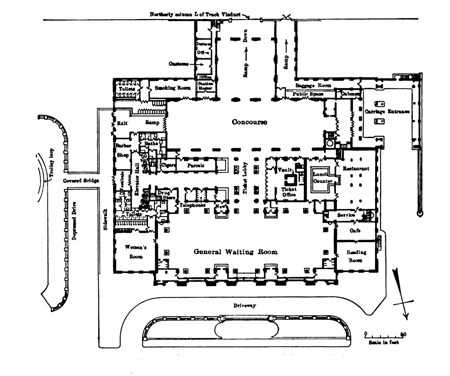

Michigan Central had no hotel, but it did have a vast waiting room, reading room, smoking room, lunch counter, elegant restaurant with vaulted ceilings like the Oyster Bar's, sleeping accommodations and offices for railroad personnel, stores and a barber shop adjoined by eight private dressing rooms equipped with bathtubs "to allow out-of-town patrons to change clothes and dress for evening appointments without going to a hotel," according to the Railway Age Gazette. This last amenity would enable one to awaken in New York's Biltmore Hotel, take a train to Detroit - perhaps sleeping overnight in a Pullman car - get a shave from a barber upon arrival, bathe and put on fresh clothes without going outside, all within an architecturally consistent user experience. To fully appreciate Detroit's Station as an extension of New York's Terminal City, Whitney Warren's Biltmore Hotel tower (left), not the bulky one he reluctantly designed above Grand Central, must be compared to Michigan Central's tower (right). Their top floors were expressed as multi-story arcades under strong, bracketed cornices. In both, vertical emphasis was provided by narrow wings, the slim faces of which have a three-bay arcade above a projecting balcony. Both towers were clad in brick above high stone bases which projected forward to relate to their neighboring stone-clad stations.

In 1981, new owners stripped the Biltmore to its steel skeleton and sheathed it in shiny anonymity just as it was rumored to be a candidate for landmark designation and the protection it would bring, a loss that makes Michigan Central a rarer piece of Warren & Wetmore's legacy.

To fully appreciate Detroit's Station as an extension of New York's Terminal City, Whitney Warren's Biltmore Hotel tower (left), not the bulky one he reluctantly designed above Grand Central, must be compared to Michigan Central's tower (right). Their top floors were expressed as multi-story arcades under strong, bracketed cornices. In both, vertical emphasis was provided by narrow wings, the slim faces of which have a three-bay arcade above a projecting balcony. Both towers were clad in brick above high stone bases which projected forward to relate to their neighboring stone-clad stations.

In 1981, new owners stripped the Biltmore to its steel skeleton and sheathed it in shiny anonymity just as it was rumored to be a candidate for landmark designation and the protection it would bring, a loss that makes Michigan Central a rarer piece of Warren & Wetmore's legacy.

Michigan Central Station was built by the George A. Fuller Company, builder of New York's Pennsylvania Station and Plaza Hotel. The contractor also built New York's iconic 1902 Flatiron Building by Daniel Burnham and much of his White City in Chicago. These buildings draped modern steel structural frames in historic forms originally determined by ancient technology. This masquerade worked well enough for low-rise construction approximating the scale of ancient or Renaissance prototypes, but poorly for skyscrapers, which had no adaptable historic precedent. The building type demanded a new style, which Louis Sullivan hit upon in his vertically attenuated Wainwright and Guaranty Buildings of the 1890s. Their influence is seen in the construction photo of Michigan Central Station above, where the tower cladding weaves continuous vertical piers over an implied horizontal underlay of darker window spandrels, marking an advancement on the Biltmore's non-directional punched openings. The resulting lattice expresses the grid of the steel skeleton while accentuating the vertical in answer to Sullivan's demand that a commercial tower "must be every inch a proud and soaring thing." While Michigan Central's tower shaft is without archaic reference, its base and top floors revert to classical form, clothing a linear steel frame in classical columns and the arches and vaults devised by ancient Romans confined to load-bearing masonry construction. Sullivan associated this denial with east-coast architects like Warren, writing:

Michigan Central Station was built by the George A. Fuller Company, builder of New York's Pennsylvania Station and Plaza Hotel. The contractor also built New York's iconic 1902 Flatiron Building by Daniel Burnham and much of his White City in Chicago. These buildings draped modern steel structural frames in historic forms originally determined by ancient technology. This masquerade worked well enough for low-rise construction approximating the scale of ancient or Renaissance prototypes, but poorly for skyscrapers, which had no adaptable historic precedent. The building type demanded a new style, which Louis Sullivan hit upon in his vertically attenuated Wainwright and Guaranty Buildings of the 1890s. Their influence is seen in the construction photo of Michigan Central Station above, where the tower cladding weaves continuous vertical piers over an implied horizontal underlay of darker window spandrels, marking an advancement on the Biltmore's non-directional punched openings. The resulting lattice expresses the grid of the steel skeleton while accentuating the vertical in answer to Sullivan's demand that a commercial tower "must be every inch a proud and soaring thing." While Michigan Central's tower shaft is without archaic reference, its base and top floors revert to classical form, clothing a linear steel frame in classical columns and the arches and vaults devised by ancient Romans confined to load-bearing masonry construction. Sullivan associated this denial with east-coast architects like Warren, writing:

The architects of Chicago welcomed the steel frame and did something with it. The architects of the East were appalled by it and could make no contribution to it.

Sullivan was himself appalled by what he saw as deference to the architecture of European empires. He would have seen in Michigan Central's classical top and bottom not the gradually evolving "new and American style" Whitney Warren peddled, but what he called "the incongruous spectacle of the infant Democracy taking its mental nourishment at the withered breast of Despotism." The station at the base of Michigan Central's tower shares Grand Central's triple arches, but has its own roof-line with a distinct lineage. The well preserved upper structure of Rome's Baths of Diocletian (left) is the model for hypothetical reconstructions of the central halls of Roman baths and basilicas, and via Beaux-Arts adoption, of Penn Station's towering waiting room (right). The waiting room's upper perimeter of arched windows and rippling gables retains the plainness of the Roman prototype.

The station at the base of Michigan Central's tower shares Grand Central's triple arches, but has its own roof-line with a distinct lineage. The well preserved upper structure of Rome's Baths of Diocletian (left) is the model for hypothetical reconstructions of the central halls of Roman baths and basilicas, and via Beaux-Arts adoption, of Penn Station's towering waiting room (right). The waiting room's upper perimeter of arched windows and rippling gables retains the plainness of the Roman prototype.

In bringing this typically unadorned rooftop form to a street-level, front-and-center position as Michigan Central's main entrance, Whitney Warren faced the challenge of giving it an appropriately dignified and ornamented presence. His solution made half-round thermal windows into arched portals and their simple gables into proper pediments, a transformation that mixed the metaphors of triumphal arch and temple portico.

In bringing this typically unadorned rooftop form to a street-level, front-and-center position as Michigan Central's main entrance, Whitney Warren faced the challenge of giving it an appropriately dignified and ornamented presence. His solution made half-round thermal windows into arched portals and their simple gables into proper pediments, a transformation that mixed the metaphors of triumphal arch and temple portico.

Warren had placed monumental arches under a simplified pediment in his design of the bulkhead for New York's Chelsea Piers, completed in 1910. These measured up to their role as city gates for liners like the Titanic, which was bound for Chelsea Piers when it sank, and the Lusitania, which made its final departure from them. The horizontal entablature that would normally complete the bottom of the pediment's triangle is broken, leaving headroom for the arch below, an unusual arrangement that would appear again at Michigan Central Station. The bulkheads of Warren & Wetmore's Chelsea Piers have gone the way of the firm's Biltmore Hotel, further raising the stakes for Michigan Central's preservation.

Warren had placed monumental arches under a simplified pediment in his design of the bulkhead for New York's Chelsea Piers, completed in 1910. These measured up to their role as city gates for liners like the Titanic, which was bound for Chelsea Piers when it sank, and the Lusitania, which made its final departure from them. The horizontal entablature that would normally complete the bottom of the pediment's triangle is broken, leaving headroom for the arch below, an unusual arrangement that would appear again at Michigan Central Station. The bulkheads of Warren & Wetmore's Chelsea Piers have gone the way of the firm's Biltmore Hotel, further raising the stakes for Michigan Central's preservation.