Convergences

Last Call for Jaume Plensa's "Echo"

Echo, a belief-defying work by Spanish sculptor Jaume Plensa (JOW'-meh PLEHN'-sah) remains on view for only two more weeks, through September 11th. Like Plensa's own Crown Fountain and Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate (aka The Bean), both in Chicago's Millennium Park, Echo is both art and crowd-pleasing phenomenon. Sadly, unlike those works, Echo is not a permanent installation. If you're a sympathetic ArchiTakes reader with adequate funds, please buy Echo and donate her to the City. If you haven't seen this sculpture yet, and even if you don't have the purchase price, do make it to Madison Square Park and take in this wonder before it vanishes back into whatever dimension it came from. Echo isn't Plensa's first giant, elongated female head, but it's hard to believe she wasn't conceived specifically for the park, with its trees, which she surreally dwarfs, and surrounding skyscrapers, whose vertical attenuation she echos. The sculpture is part of Mad. Sq. Art's rotating exhibit series. Its accompanying plaque reads: "Inspired by the myth of the Greek nymph Echo, Plensa's sculpture depicts the artist's nine-year old neighbor in Barcelona, lost in a state of thoughts and dreams. Standing 44-feet tall at the center of Madison Square Park's expansive Oval Lawn, Echo's towering stature and white marble-dusted surface harmoniously reflect the historic limestone buildings that surround the park. Both monumental in size and inviting in subject, the peaceful visage of Echo creates a tranquil and introspective atmosphere amid the cacophony of central Manhattan."

Echo, a belief-defying work by Spanish sculptor Jaume Plensa (JOW'-meh PLEHN'-sah) remains on view for only two more weeks, through September 11th. Like Plensa's own Crown Fountain and Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate (aka The Bean), both in Chicago's Millennium Park, Echo is both art and crowd-pleasing phenomenon. Sadly, unlike those works, Echo is not a permanent installation. If you're a sympathetic ArchiTakes reader with adequate funds, please buy Echo and donate her to the City. If you haven't seen this sculpture yet, and even if you don't have the purchase price, do make it to Madison Square Park and take in this wonder before it vanishes back into whatever dimension it came from. Echo isn't Plensa's first giant, elongated female head, but it's hard to believe she wasn't conceived specifically for the park, with its trees, which she surreally dwarfs, and surrounding skyscrapers, whose vertical attenuation she echos. The sculpture is part of Mad. Sq. Art's rotating exhibit series. Its accompanying plaque reads: "Inspired by the myth of the Greek nymph Echo, Plensa's sculpture depicts the artist's nine-year old neighbor in Barcelona, lost in a state of thoughts and dreams. Standing 44-feet tall at the center of Madison Square Park's expansive Oval Lawn, Echo's towering stature and white marble-dusted surface harmoniously reflect the historic limestone buildings that surround the park. Both monumental in size and inviting in subject, the peaceful visage of Echo creates a tranquil and introspective atmosphere amid the cacophony of central Manhattan."

By day, Echo's still, smooth white surface and airbrushed shadows contrast with the choppy, fine-grained background of the park's leaves to enhance its unreality. "Viewed from a distance at night," Ken Johnson has written in the New York Times, "when it is bathed in the bright light of lamps around its base, it seems to glow, a silently plaintive specter conjured, maybe, by the guilty conscience of a rapacious modernity." Johnson continues that Echo "evokes something neglected, a soulful road not taken." This might just be one man's arty free association but for the very real way Echo whacks the average Joe on the head, stopping him in his tracks to say "it looks like a hologram," or "it looks two-dimensional," or "like it's not really there" or simply "not real," as he joins the crowd taking cell phone pictures. "Road not taken" seems an understatement compared to the primitive brain's first impression; Echo's white ellipse looks like a portal to another world, or to the lost wonder of this one, cut through the green wall of the park's trees. The immediate visual effect is impossible to convey in pictures and a testament to Plensa's huge technical skill. He's found the subtlest of means to manipulate his material into immateriality.

By day, Echo's still, smooth white surface and airbrushed shadows contrast with the choppy, fine-grained background of the park's leaves to enhance its unreality. "Viewed from a distance at night," Ken Johnson has written in the New York Times, "when it is bathed in the bright light of lamps around its base, it seems to glow, a silently plaintive specter conjured, maybe, by the guilty conscience of a rapacious modernity." Johnson continues that Echo "evokes something neglected, a soulful road not taken." This might just be one man's arty free association but for the very real way Echo whacks the average Joe on the head, stopping him in his tracks to say "it looks like a hologram," or "it looks two-dimensional," or "like it's not really there" or simply "not real," as he joins the crowd taking cell phone pictures. "Road not taken" seems an understatement compared to the primitive brain's first impression; Echo's white ellipse looks like a portal to another world, or to the lost wonder of this one, cut through the green wall of the park's trees. The immediate visual effect is impossible to convey in pictures and a testament to Plensa's huge technical skill. He's found the subtlest of means to manipulate his material into immateriality.

Life's specifics distract us from its fundamental mystery. The ubiquitous iPhone-absorbed city pedestrian, oblivious to even a park's surroundings, may remind us of Thoreau's observation that our lives are frittered away by detail. "Every time I've come here, I've been fascinated with the stream of people passing through," Jaume Plensa says of Madison Square Park, in a Times piece by Carol Kino. "Many times we talk and talk, but we are not sure if we are talking with our own words or repeating just messages in the air. My intention is to offer something so beautiful that people have an immediate reaction, so they think, 'What's happening?' And then maybe they can listen a bit to themselves."

Life's specifics distract us from its fundamental mystery. The ubiquitous iPhone-absorbed city pedestrian, oblivious to even a park's surroundings, may remind us of Thoreau's observation that our lives are frittered away by detail. "Every time I've come here, I've been fascinated with the stream of people passing through," Jaume Plensa says of Madison Square Park, in a Times piece by Carol Kino. "Many times we talk and talk, but we are not sure if we are talking with our own words or repeating just messages in the air. My intention is to offer something so beautiful that people have an immediate reaction, so they think, 'What's happening?' And then maybe they can listen a bit to themselves."

Echo arrests even the cell phone, source of outer voices and the distracting demands of the moment.

Echo arrests even the cell phone, source of outer voices and the distracting demands of the moment.

Like so many visitors to the area, Echo turns toward the Flatiron Building. Architect Daniel Burnham's 1902 icon played muse to Steichen, Stieglitz and countless other artists, and still draws cameras as compulsively as Echo herself. Stieglitz said the Flatiron "...appeared to be moving toward

Like so many visitors to the area, Echo turns toward the Flatiron Building. Architect Daniel Burnham's 1902 icon played muse to Steichen, Stieglitz and countless other artists, and still draws cameras as compulsively as Echo herself. Stieglitz said the Flatiron "...appeared to be moving toward  Exegesis aside, Echo bears an undeniable family resemblance to the Flatiron, New York's greatest public sculpture. (Sorry, Lady.) The Flatiron's enduring appeal and inherent sculptural interest come of its deviation from the expected; it would be just another building if it had four sides and right-angled corners. God is in the doctored vanishing points. Echo similarly distorts an iconic form, the human head, imprinted on our infantile psyches from day one. The sculpture derives authority from this familiarity and from its sheer scale, as the Flatiron does from being a skyscraper, or a Richard Serra sculpture from its two-inch thick steel plates. The mind instinctively takes such established and impressive objects seriously, and is itself thrown off balance when they are unmoored from their usual behaviour; it may be jarred awake to the unlikeliness of all the rest of life and temporarily restored to the wonder of childhood, perhaps the highest purpose of art. The funhouse aspect of distortion has the broad appeal of an amusement park, but its suspension of rules is a legitimate art strategy. It's what raises Echo above a clichéd image of new age peace and contentment.

Exegesis aside, Echo bears an undeniable family resemblance to the Flatiron, New York's greatest public sculpture. (Sorry, Lady.) The Flatiron's enduring appeal and inherent sculptural interest come of its deviation from the expected; it would be just another building if it had four sides and right-angled corners. God is in the doctored vanishing points. Echo similarly distorts an iconic form, the human head, imprinted on our infantile psyches from day one. The sculpture derives authority from this familiarity and from its sheer scale, as the Flatiron does from being a skyscraper, or a Richard Serra sculpture from its two-inch thick steel plates. The mind instinctively takes such established and impressive objects seriously, and is itself thrown off balance when they are unmoored from their usual behaviour; it may be jarred awake to the unlikeliness of all the rest of life and temporarily restored to the wonder of childhood, perhaps the highest purpose of art. The funhouse aspect of distortion has the broad appeal of an amusement park, but its suspension of rules is a legitimate art strategy. It's what raises Echo above a clichéd image of new age peace and contentment.

In citing the towers of San Gimignano as his inspiration for the Torres Satélite, Luis Barragán kept critics from observing another likely source, the Flatiron Building. These 1957 traffic island towers were designed to welcome visitors to the Ciudad Satélite, a suburb of Mexico City. Whether Barragán had the Flatiron Building in mind or not, its visual dynamic is undeniably present in his towers, confirming its independent validity as sculpture, and the potential of architecture to re-impart the modern world with wonder the way art can. Barrágan was deeply concerned with bringing magic to the contemporary world: "I think that the ideal space must contain elements of magic, serenity, sorcery and mystery." As did the Flatiron Building, Plensa's Echo answers this call.

Now that you've agreed to buy Echo for New York (and thank you very much) the only question is where to put her. Great as she looks facing the Flatiron, the folks at Mad. Sq. Art have to make way for their next installation. How about Bryant Park? It has the green backdrop that works so well, and is an epicenter of mythic skyscrapers. Her "white marble-dusted surface" could "harmoniously reflect" the newly restored marble of the New York Public Library instead of the mere limestone buildings around Madison Square Park. Let's work on it.

In citing the towers of San Gimignano as his inspiration for the Torres Satélite, Luis Barragán kept critics from observing another likely source, the Flatiron Building. These 1957 traffic island towers were designed to welcome visitors to the Ciudad Satélite, a suburb of Mexico City. Whether Barragán had the Flatiron Building in mind or not, its visual dynamic is undeniably present in his towers, confirming its independent validity as sculpture, and the potential of architecture to re-impart the modern world with wonder the way art can. Barrágan was deeply concerned with bringing magic to the contemporary world: "I think that the ideal space must contain elements of magic, serenity, sorcery and mystery." As did the Flatiron Building, Plensa's Echo answers this call.

Now that you've agreed to buy Echo for New York (and thank you very much) the only question is where to put her. Great as she looks facing the Flatiron, the folks at Mad. Sq. Art have to make way for their next installation. How about Bryant Park? It has the green backdrop that works so well, and is an epicenter of mythic skyscrapers. Her "white marble-dusted surface" could "harmoniously reflect" the newly restored marble of the New York Public Library instead of the mere limestone buildings around Madison Square Park. Let's work on it.

Last Call for Jaume Plensa's "Echo"

Echo, a belief-defying work by Spanish sculptor Jaume Plensa (JOW'-meh PLEHN'-sah) remains on view for only two more weeks, through September 11th. Like Plensa's own Crown Fountain and Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate (aka The Bean), both in Chicago's Millennium Park, Echo is both art and crowd-pleasing phenomenon. Sadly, unlike those works, Echo is not a permanent installation. If you're a sympathetic ArchiTakes reader with adequate funds, please buy Echo and donate her to the City. If you haven't seen this sculpture yet, and even if you don't have the purchase price, do make it to Madison Square Park and take in this wonder before it vanishes back into whatever dimension it came from. Echo isn't Plensa's first giant, elongated female head, but it's hard to believe she wasn't conceived specifically for the park, with its trees, which she surreally dwarfs, and surrounding skyscrapers, whose vertical attenuation she echos. The sculpture is part of Mad. Sq. Art's rotating exhibit series. Its accompanying plaque reads: "Inspired by the myth of the Greek nymph Echo, Plensa's sculpture depicts the artist's nine-year old neighbor in Barcelona, lost in a state of thoughts and dreams. Standing 44-feet tall at the center of Madison Square Park's expansive Oval Lawn, Echo's towering stature and white marble-dusted surface harmoniously reflect the historic limestone buildings that surround the park. Both monumental in size and inviting in subject, the peaceful visage of Echo creates a tranquil and introspective atmosphere amid the cacophony of central Manhattan."

Echo, a belief-defying work by Spanish sculptor Jaume Plensa (JOW'-meh PLEHN'-sah) remains on view for only two more weeks, through September 11th. Like Plensa's own Crown Fountain and Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate (aka The Bean), both in Chicago's Millennium Park, Echo is both art and crowd-pleasing phenomenon. Sadly, unlike those works, Echo is not a permanent installation. If you're a sympathetic ArchiTakes reader with adequate funds, please buy Echo and donate her to the City. If you haven't seen this sculpture yet, and even if you don't have the purchase price, do make it to Madison Square Park and take in this wonder before it vanishes back into whatever dimension it came from. Echo isn't Plensa's first giant, elongated female head, but it's hard to believe she wasn't conceived specifically for the park, with its trees, which she surreally dwarfs, and surrounding skyscrapers, whose vertical attenuation she echos. The sculpture is part of Mad. Sq. Art's rotating exhibit series. Its accompanying plaque reads: "Inspired by the myth of the Greek nymph Echo, Plensa's sculpture depicts the artist's nine-year old neighbor in Barcelona, lost in a state of thoughts and dreams. Standing 44-feet tall at the center of Madison Square Park's expansive Oval Lawn, Echo's towering stature and white marble-dusted surface harmoniously reflect the historic limestone buildings that surround the park. Both monumental in size and inviting in subject, the peaceful visage of Echo creates a tranquil and introspective atmosphere amid the cacophony of central Manhattan."

By day, Echo's still, smooth white surface and airbrushed shadows contrast with the choppy, fine-grained background of the park's leaves to enhance its unreality. "Viewed from a distance at night," Ken Johnson has written in the New York Times, "when it is bathed in the bright light of lamps around its base, it seems to glow, a silently plaintive specter conjured, maybe, by the guilty conscience of a rapacious modernity." Johnson continues that Echo "evokes something neglected, a soulful road not taken." This might just be one man's arty free association but for the very real way Echo whacks the average Joe on the head, stopping him in his tracks to say "it looks like a hologram," or "it looks two-dimensional," or "like it's not really there" or simply "not real," as he joins the crowd taking cell phone pictures. "Road not taken" seems an understatement compared to the primitive brain's first impression; Echo's white ellipse looks like a portal to another world, or to the lost wonder of this one, cut through the green wall of the park's trees. The immediate visual effect is impossible to convey in pictures and a testament to Plensa's huge technical skill. He's found the subtlest of means to manipulate his material into immateriality.

By day, Echo's still, smooth white surface and airbrushed shadows contrast with the choppy, fine-grained background of the park's leaves to enhance its unreality. "Viewed from a distance at night," Ken Johnson has written in the New York Times, "when it is bathed in the bright light of lamps around its base, it seems to glow, a silently plaintive specter conjured, maybe, by the guilty conscience of a rapacious modernity." Johnson continues that Echo "evokes something neglected, a soulful road not taken." This might just be one man's arty free association but for the very real way Echo whacks the average Joe on the head, stopping him in his tracks to say "it looks like a hologram," or "it looks two-dimensional," or "like it's not really there" or simply "not real," as he joins the crowd taking cell phone pictures. "Road not taken" seems an understatement compared to the primitive brain's first impression; Echo's white ellipse looks like a portal to another world, or to the lost wonder of this one, cut through the green wall of the park's trees. The immediate visual effect is impossible to convey in pictures and a testament to Plensa's huge technical skill. He's found the subtlest of means to manipulate his material into immateriality.

Life's specifics distract us from its fundamental mystery. The ubiquitous iPhone-absorbed city pedestrian, oblivious to even a park's surroundings, may remind us of Thoreau's observation that our lives are frittered away by detail. "Every time I've come here, I've been fascinated with the stream of people passing through," Jaume Plensa says of Madison Square Park, in a Times piece by Carol Kino. "Many times we talk and talk, but we are not sure if we are talking with our own words or repeating just messages in the air. My intention is to offer something so beautiful that people have an immediate reaction, so they think, 'What's happening?' And then maybe they can listen a bit to themselves."

Life's specifics distract us from its fundamental mystery. The ubiquitous iPhone-absorbed city pedestrian, oblivious to even a park's surroundings, may remind us of Thoreau's observation that our lives are frittered away by detail. "Every time I've come here, I've been fascinated with the stream of people passing through," Jaume Plensa says of Madison Square Park, in a Times piece by Carol Kino. "Many times we talk and talk, but we are not sure if we are talking with our own words or repeating just messages in the air. My intention is to offer something so beautiful that people have an immediate reaction, so they think, 'What's happening?' And then maybe they can listen a bit to themselves."

Echo arrests even the cell phone, source of outer voices and the distracting demands of the moment.

Echo arrests even the cell phone, source of outer voices and the distracting demands of the moment.

Like so many visitors to the area, Echo turns toward the Flatiron Building. Architect Daniel Burnham's 1902 icon played muse to Steichen, Stieglitz and countless other artists, and still draws cameras as compulsively as Echo herself. Stieglitz said the Flatiron "...appeared to be moving toward

Like so many visitors to the area, Echo turns toward the Flatiron Building. Architect Daniel Burnham's 1902 icon played muse to Steichen, Stieglitz and countless other artists, and still draws cameras as compulsively as Echo herself. Stieglitz said the Flatiron "...appeared to be moving toward  Exegesis aside, Echo bears an undeniable family resemblance to the Flatiron, New York's greatest public sculpture. (Sorry, Lady.) The Flatiron's enduring appeal and inherent sculptural interest come of its deviation from the expected; it would be just another building if it had four sides and right-angled corners. God is in the doctored vanishing points. Echo similarly distorts an iconic form, the human head, imprinted on our infantile psyches from day one. The sculpture derives authority from this familiarity and from its sheer scale, as the Flatiron does from being a skyscraper, or a Richard Serra sculpture from its two-inch thick steel plates. The mind instinctively takes such established and impressive objects seriously, and is itself thrown off balance when they are unmoored from their usual behaviour; it may be jarred awake to the unlikeliness of all the rest of life and temporarily restored to the wonder of childhood, perhaps the highest purpose of art. The funhouse aspect of distortion has the broad appeal of an amusement park, but its suspension of rules is a legitimate art strategy. It's what raises Echo above a clichéd image of new age peace and contentment.

Exegesis aside, Echo bears an undeniable family resemblance to the Flatiron, New York's greatest public sculpture. (Sorry, Lady.) The Flatiron's enduring appeal and inherent sculptural interest come of its deviation from the expected; it would be just another building if it had four sides and right-angled corners. God is in the doctored vanishing points. Echo similarly distorts an iconic form, the human head, imprinted on our infantile psyches from day one. The sculpture derives authority from this familiarity and from its sheer scale, as the Flatiron does from being a skyscraper, or a Richard Serra sculpture from its two-inch thick steel plates. The mind instinctively takes such established and impressive objects seriously, and is itself thrown off balance when they are unmoored from their usual behaviour; it may be jarred awake to the unlikeliness of all the rest of life and temporarily restored to the wonder of childhood, perhaps the highest purpose of art. The funhouse aspect of distortion has the broad appeal of an amusement park, but its suspension of rules is a legitimate art strategy. It's what raises Echo above a clichéd image of new age peace and contentment.

In citing the towers of San Gimignano as his inspiration for the Torres Satélite, Luis Barragán kept critics from observing another likely source, the Flatiron Building. These 1957 traffic island towers were designed to welcome visitors to the Ciudad Satélite, a suburb of Mexico City. Whether Barragán had the Flatiron Building in mind or not, its visual dynamic is undeniably present in his towers, confirming its independent validity as sculpture, and the potential of architecture to re-impart the modern world with wonder the way art can. Barrágan was deeply concerned with bringing magic to the contemporary world: "I think that the ideal space must contain elements of magic, serenity, sorcery and mystery." As did the Flatiron Building, Plensa's Echo answers this call.

Now that you've agreed to buy Echo for New York (and thank you very much) the only question is where to put her. Great as she looks facing the Flatiron, the folks at Mad. Sq. Art have to make way for their next installation. How about Bryant Park? It has the green backdrop that works so well, and is an epicenter of mythic skyscrapers. Her "white marble-dusted surface" could "harmoniously reflect" the newly restored marble of the New York Public Library instead of the mere limestone buildings around Madison Square Park. Let's work on it.

In citing the towers of San Gimignano as his inspiration for the Torres Satélite, Luis Barragán kept critics from observing another likely source, the Flatiron Building. These 1957 traffic island towers were designed to welcome visitors to the Ciudad Satélite, a suburb of Mexico City. Whether Barragán had the Flatiron Building in mind or not, its visual dynamic is undeniably present in his towers, confirming its independent validity as sculpture, and the potential of architecture to re-impart the modern world with wonder the way art can. Barrágan was deeply concerned with bringing magic to the contemporary world: "I think that the ideal space must contain elements of magic, serenity, sorcery and mystery." As did the Flatiron Building, Plensa's Echo answers this call.

Now that you've agreed to buy Echo for New York (and thank you very much) the only question is where to put her. Great as she looks facing the Flatiron, the folks at Mad. Sq. Art have to make way for their next installation. How about Bryant Park? It has the green backdrop that works so well, and is an epicenter of mythic skyscrapers. Her "white marble-dusted surface" could "harmoniously reflect" the newly restored marble of the New York Public Library instead of the mere limestone buildings around Madison Square Park. Let's work on it.

Midtown Undone

Photographed last week, Midtown Plaza's piecemeal demolition brings the look of a ship breaking yard to the skyline of Rochester, New York. The image may be bracing to those who remember the project's promise of urban renewal when it was completed in 1962, to the design of urban planner Victor Gruen. According to the Wikipedia entry on Midtown, "Gruen was at the height of his influence when Midtown was completed and the project attracted international attention, including a nationally televised feature report on NBC-TV's Huntley-Brinkley newscast the night of its opening in April 1962. City officials and planners from around the globe came to see Gruen's solution to the mid-century urban crisis. Midtown won several design awards." A Jewish refugee from Nazi occupied Vienna, Gruen said he arrived in America with "an architectural degree, eight dollars, and no English." He went from designing Fifth Avenue boutiques to a role as one of America's premier urban planners. Melding his insights into consumer psychology with a conviction that retail spaces could create communities, Gruen invented the shopping mall. He strove to bring the urbanity of his native Vienna and Europe to America, claiming the Milan Galleria was his model for the mall. In 2004, Malcolm Gladwell wrote in The New Yorker that "Victor Gruen may well have been the most influential architect of the twentieth century" for his creation of the pervasive archetype. Gruen's impact continues to be registered. Gladwell's appraisal followed on the publication of Jeffrey Hardwick's 2004 book, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. A decade ago, the media theorist and concept-coiner Douglas Rushkoff began popularizing the Gruen Transfer, also known as the Gruen Effect, by which shoppers are intentionally disoriented and distracted by the retail environment, so they'll lose focus and succumb to impulse buying. Since 2008, The Gruen Transfer has been the title of an Australian TV series on advertising. In 2009, Anette Baldauf and Katharina Weingartner released the documentary, The Gruen Effect: Victor Gruen and the Shopping Mall.

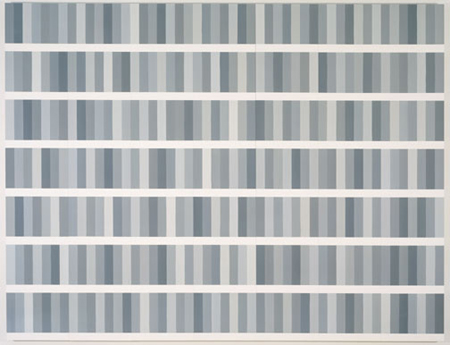

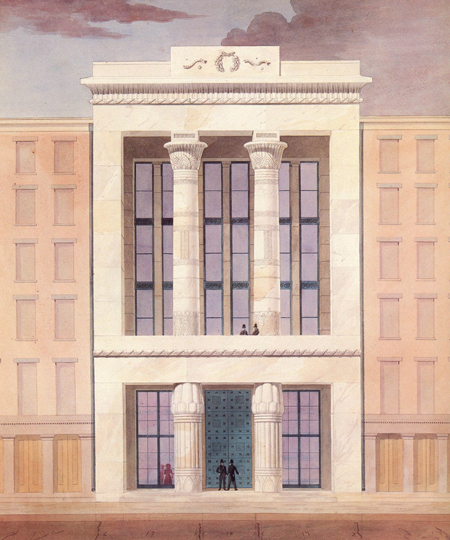

Photographed last week, Midtown Plaza's piecemeal demolition brings the look of a ship breaking yard to the skyline of Rochester, New York. The image may be bracing to those who remember the project's promise of urban renewal when it was completed in 1962, to the design of urban planner Victor Gruen. According to the Wikipedia entry on Midtown, "Gruen was at the height of his influence when Midtown was completed and the project attracted international attention, including a nationally televised feature report on NBC-TV's Huntley-Brinkley newscast the night of its opening in April 1962. City officials and planners from around the globe came to see Gruen's solution to the mid-century urban crisis. Midtown won several design awards." A Jewish refugee from Nazi occupied Vienna, Gruen said he arrived in America with "an architectural degree, eight dollars, and no English." He went from designing Fifth Avenue boutiques to a role as one of America's premier urban planners. Melding his insights into consumer psychology with a conviction that retail spaces could create communities, Gruen invented the shopping mall. He strove to bring the urbanity of his native Vienna and Europe to America, claiming the Milan Galleria was his model for the mall. In 2004, Malcolm Gladwell wrote in The New Yorker that "Victor Gruen may well have been the most influential architect of the twentieth century" for his creation of the pervasive archetype. Gruen's impact continues to be registered. Gladwell's appraisal followed on the publication of Jeffrey Hardwick's 2004 book, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. A decade ago, the media theorist and concept-coiner Douglas Rushkoff began popularizing the Gruen Transfer, also known as the Gruen Effect, by which shoppers are intentionally disoriented and distracted by the retail environment, so they'll lose focus and succumb to impulse buying. Since 2008, The Gruen Transfer has been the title of an Australian TV series on advertising. In 2009, Anette Baldauf and Katharina Weingartner released the documentary, The Gruen Effect: Victor Gruen and the Shopping Mall.  Midtown Plaza introduced the nation's first urban shopping mall, within a mixed-use megastructure. The project included 2,000 underground parking spaces, a 300-seat auditorium, and an office block with a hotel above (here shown disappearing). A restaurant projected from the base of the hotel element, providing dramatic views from what was Rochester's tallest building. Two skyways connected the complex to nearby office buildings. Gruen wrote, "It is our belief that there is much need for actual shopping centers - market places that are also centers of community and cultural activity." In its coverage of Midtown Plaza, Architectural Forum magazine quoted Gruen as saying, "We wanted to create a town square with urbane qualities. At the same time, the Plaza is important as a setting for cultural and social events - concerts, fashion shows, balls, and those activities which one connects with urban life." Gruen's formula for urban renewal included a downtown mall, ample parking, and a ring road to ease car access to parking. The ring road was adopted from his native Vienna. Gruen found one ready made in Rochester, whose residents may be stunned to learn that someone once saw Vienna's Ringstrasse in their unassuming Inner Loop. Despite its importance as an artifact of American urban planning, Midtown isn't the sort of project that gets preserved. The recent Cronocaos exhibition organized by Rem Koolhaas and his OMA partner Shohei Shigematsu, accused preservationists of scenographically cherry picking what to preserve and whitewashing urban evolution. In his review of the show for the New York Times, Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote, "This phenomenon is coupled with another disturbing trend: the selective demolition of the most socially ambitious architecture of the 1960s and ’70s — the last period when architects were able to do large-scale public work. That style has been condemned as a monstrous expression of Modernism." Examples noted in the show included East Berlin's Palast der Republik and Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower. Koolhaas' own respect for ambitious mega-projects would seem sympathetic to Midtown Plaza, if malls weren't the essence of the air-conditioned and escalatored nowhere he's named "Junkspace."

Midtown Plaza introduced the nation's first urban shopping mall, within a mixed-use megastructure. The project included 2,000 underground parking spaces, a 300-seat auditorium, and an office block with a hotel above (here shown disappearing). A restaurant projected from the base of the hotel element, providing dramatic views from what was Rochester's tallest building. Two skyways connected the complex to nearby office buildings. Gruen wrote, "It is our belief that there is much need for actual shopping centers - market places that are also centers of community and cultural activity." In its coverage of Midtown Plaza, Architectural Forum magazine quoted Gruen as saying, "We wanted to create a town square with urbane qualities. At the same time, the Plaza is important as a setting for cultural and social events - concerts, fashion shows, balls, and those activities which one connects with urban life." Gruen's formula for urban renewal included a downtown mall, ample parking, and a ring road to ease car access to parking. The ring road was adopted from his native Vienna. Gruen found one ready made in Rochester, whose residents may be stunned to learn that someone once saw Vienna's Ringstrasse in their unassuming Inner Loop. Despite its importance as an artifact of American urban planning, Midtown isn't the sort of project that gets preserved. The recent Cronocaos exhibition organized by Rem Koolhaas and his OMA partner Shohei Shigematsu, accused preservationists of scenographically cherry picking what to preserve and whitewashing urban evolution. In his review of the show for the New York Times, Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote, "This phenomenon is coupled with another disturbing trend: the selective demolition of the most socially ambitious architecture of the 1960s and ’70s — the last period when architects were able to do large-scale public work. That style has been condemned as a monstrous expression of Modernism." Examples noted in the show included East Berlin's Palast der Republik and Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower. Koolhaas' own respect for ambitious mega-projects would seem sympathetic to Midtown Plaza, if malls weren't the essence of the air-conditioned and escalatored nowhere he's named "Junkspace."  In his 1964 book, The Heart of Our Cities: The Urban Crisis, Diagnosis and Cure, Gruen prominently featured Midtown Plaza, documenting its advertised social role with this newspaper photo of a high school dance on the floor of its shopping mall. Helped by a tailwind from the 1960s economic boom, Midtown was initially an undeniable success. Within twenty years, it proved to have been a mere eddy against the inexorable tide of white flight and sprawl fueled by the more common suburban version of the mall. Writing in the 2002 book, The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, contributor Sze Tsung Leong writes: "Victor Gruen, widely acknowledged as the inventor of the shopping mall, was, in the end, not interested in shopping. Instead, the shopping mall was a vehicle toward his real ambition: to redefine the contemporary city. For Gruen, the mall was the new city." Leong quotes Gruen's 1960 book, Shopping Towns USA: "By affording opportunities for social life and recreation in a protected pedestrian environment, by incorporating civic and educational facilities, shopping centers can fill an existing void. They can provide the needed place and opportunity for participation in modern community life that the ancient Greek Agora, the Medieval Market Place and our Town Squares provided in the past." Leong observes, "At he same time that Victor Gruen was configuring the mall to provide civic functions, he was also envisioning the suburban shopping mall as a model for downtown revitalization." Midtown Plaza would be the first implementation of this vision. Although the shopping mall would indeed serve a social role, particularly among teenagers, the idea that it would be the new Agora now ranks with early hopes that TV would be educational.

In his 1964 book, The Heart of Our Cities: The Urban Crisis, Diagnosis and Cure, Gruen prominently featured Midtown Plaza, documenting its advertised social role with this newspaper photo of a high school dance on the floor of its shopping mall. Helped by a tailwind from the 1960s economic boom, Midtown was initially an undeniable success. Within twenty years, it proved to have been a mere eddy against the inexorable tide of white flight and sprawl fueled by the more common suburban version of the mall. Writing in the 2002 book, The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, contributor Sze Tsung Leong writes: "Victor Gruen, widely acknowledged as the inventor of the shopping mall, was, in the end, not interested in shopping. Instead, the shopping mall was a vehicle toward his real ambition: to redefine the contemporary city. For Gruen, the mall was the new city." Leong quotes Gruen's 1960 book, Shopping Towns USA: "By affording opportunities for social life and recreation in a protected pedestrian environment, by incorporating civic and educational facilities, shopping centers can fill an existing void. They can provide the needed place and opportunity for participation in modern community life that the ancient Greek Agora, the Medieval Market Place and our Town Squares provided in the past." Leong observes, "At he same time that Victor Gruen was configuring the mall to provide civic functions, he was also envisioning the suburban shopping mall as a model for downtown revitalization." Midtown Plaza would be the first implementation of this vision. Although the shopping mall would indeed serve a social role, particularly among teenagers, the idea that it would be the new Agora now ranks with early hopes that TV would be educational.  Banking on a single project to revitalize a city might seem quaint but for the recent example of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which so successfully jump-started the Basque town's economy as to give urbanism the Bilbao Effect. (Photo: User:MykReeve.) Gehry worked for Victor Gruen in the 1950s when Midtown Plaza was being designed and is said to have been greatly influenced by his views on city planning. It was during this time that Gehry changed his name from Goldberg as Gruen had changed his own from Grünbaum, immigrants self-inventing in American Gatz-to-Gatsby fashion. Early in his own practice, Gehry used his experience in Gruen's office to design several shopping malls including Santa Monica Place. In Bilbao, Gehry's building inverts Gruen's urban mall strategy, making culture a vehicle for commerce. The commercialization of museums has been much commented on, as their shops take up increasing amounts of space and multiple locations within, while sprouting external outposts with no museum attached at all.

Banking on a single project to revitalize a city might seem quaint but for the recent example of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which so successfully jump-started the Basque town's economy as to give urbanism the Bilbao Effect. (Photo: User:MykReeve.) Gehry worked for Victor Gruen in the 1950s when Midtown Plaza was being designed and is said to have been greatly influenced by his views on city planning. It was during this time that Gehry changed his name from Goldberg as Gruen had changed his own from Grünbaum, immigrants self-inventing in American Gatz-to-Gatsby fashion. Early in his own practice, Gehry used his experience in Gruen's office to design several shopping malls including Santa Monica Place. In Bilbao, Gehry's building inverts Gruen's urban mall strategy, making culture a vehicle for commerce. The commercialization of museums has been much commented on, as their shops take up increasing amounts of space and multiple locations within, while sprouting external outposts with no museum attached at all.  The 2001 Prada flagship store is the design of OMA, the architecture firm of Rem Koolhaas, another contributor to The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. The design seems to respond particularly to a post-Gruen world where shopping has been established as the answer to everything. According to OMA's website, the design is part of the firm's "ongoing research into shopping, arguably the last remaining form of public activity. . . . As museums, libraries, airports, hospitals, and schools become increasingly indistinguishable from shopping centres, their adoption of retail for survival has unleashed an enormous wave of commercial entrapment that has transformed museum-goers, researchers, travelers, patients, and students into customers. The result is a deadening loss of variety. What were once distinct activities no longer retain the uniqueness that gave them richness. What if the equation were reversed, so that customers were no longer identified as consumers, but recognized as researchers, students, patients, museum-goers? What if the shopping experience were not one of impoverishment, but of enrichment?" The Prada store's response is its dual-purpose central wave. OMA's website explains how it works: "On one side, the slope has steps – ostensibly for displaying shoes and accessories – that can be used as a seating area, facing a stage that unfolds from the other side of the wave. The store thus becomes a venue for film screenings, performances, and lectures." An impressive amount of valuable retail space was dedicated to this conceit, which appears mainly to justify the Koolhaas trademark of blended floor levels. Asked about the frequency of the stage's use, the store's management referred the question to Prada's corporate office which referred it in turn to its public relations department, approachable only by fax, and so far unresponsive. Victor Gruen had ruefully learned decades earlier that when push comes to shove between commerce and culture, commerce wins. Prada's entire SoHo setting has itself lost most of its distinctive urban character in its transition to an outdoor shopping mall dominated by national chains. Victor Gruen ultimately regretted the impact of the mall archetype he had created. According to Jeffrey Hardwick's Mall Maker, in a 1978 London speech he criticized Americans for perverting his ideas, saying "I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments." Hardwick writes that at seventy-five, "Gruen had reached the end of his faith in the power of architectural solutions," continuing that "In Gruen's opinion, the shopping center had become focused solely on its primary goal of promoting retail and had abandoned its possible role in creating new communities." His suburban malls had not only failed to bear civic fruit, but had helped kill the city itself, while putting the American car culture he despised on steroids. Mall Maker quotes one of Gruen's business partners, Karl Van Leuven, describing an early 1950s visit with Gruen to the site of their gigantic Northland mall outside Detroit: "'There were all those monstrous earth moving machines pushing and shoving and changing the face of some 200 acres,' he recalled. After watching this impressive effort, Gruen turned to Van Leuven and softly said, 'My God but we've got a lot of nerve.'" Given the greater impact, on Detroit and the American city and landscape, Oppenheimer's "destroyer of worlds" moment comes to mind. The genie was out of the bottle. In a 1994 essay, "What Ever Happened to Urbanism?" Rem Koolhaas described an out of control urbanism that will be replaced by "an ideology: to accept what exists. We were making sand castles. Now we swim in the sea that swept them away." Many see only resignation in his stance, but old-school urbanism can be seen washing away this month on the Rochester skyline.

The 2001 Prada flagship store is the design of OMA, the architecture firm of Rem Koolhaas, another contributor to The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. The design seems to respond particularly to a post-Gruen world where shopping has been established as the answer to everything. According to OMA's website, the design is part of the firm's "ongoing research into shopping, arguably the last remaining form of public activity. . . . As museums, libraries, airports, hospitals, and schools become increasingly indistinguishable from shopping centres, their adoption of retail for survival has unleashed an enormous wave of commercial entrapment that has transformed museum-goers, researchers, travelers, patients, and students into customers. The result is a deadening loss of variety. What were once distinct activities no longer retain the uniqueness that gave them richness. What if the equation were reversed, so that customers were no longer identified as consumers, but recognized as researchers, students, patients, museum-goers? What if the shopping experience were not one of impoverishment, but of enrichment?" The Prada store's response is its dual-purpose central wave. OMA's website explains how it works: "On one side, the slope has steps – ostensibly for displaying shoes and accessories – that can be used as a seating area, facing a stage that unfolds from the other side of the wave. The store thus becomes a venue for film screenings, performances, and lectures." An impressive amount of valuable retail space was dedicated to this conceit, which appears mainly to justify the Koolhaas trademark of blended floor levels. Asked about the frequency of the stage's use, the store's management referred the question to Prada's corporate office which referred it in turn to its public relations department, approachable only by fax, and so far unresponsive. Victor Gruen had ruefully learned decades earlier that when push comes to shove between commerce and culture, commerce wins. Prada's entire SoHo setting has itself lost most of its distinctive urban character in its transition to an outdoor shopping mall dominated by national chains. Victor Gruen ultimately regretted the impact of the mall archetype he had created. According to Jeffrey Hardwick's Mall Maker, in a 1978 London speech he criticized Americans for perverting his ideas, saying "I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments." Hardwick writes that at seventy-five, "Gruen had reached the end of his faith in the power of architectural solutions," continuing that "In Gruen's opinion, the shopping center had become focused solely on its primary goal of promoting retail and had abandoned its possible role in creating new communities." His suburban malls had not only failed to bear civic fruit, but had helped kill the city itself, while putting the American car culture he despised on steroids. Mall Maker quotes one of Gruen's business partners, Karl Van Leuven, describing an early 1950s visit with Gruen to the site of their gigantic Northland mall outside Detroit: "'There were all those monstrous earth moving machines pushing and shoving and changing the face of some 200 acres,' he recalled. After watching this impressive effort, Gruen turned to Van Leuven and softly said, 'My God but we've got a lot of nerve.'" Given the greater impact, on Detroit and the American city and landscape, Oppenheimer's "destroyer of worlds" moment comes to mind. The genie was out of the bottle. In a 1994 essay, "What Ever Happened to Urbanism?" Rem Koolhaas described an out of control urbanism that will be replaced by "an ideology: to accept what exists. We were making sand castles. Now we swim in the sea that swept them away." Many see only resignation in his stance, but old-school urbanism can be seen washing away this month on the Rochester skyline.

Midtown Undone

Photographed last week, Midtown Plaza's piecemeal demolition brings the look of a ship breaking yard to the skyline of Rochester, New York. The image may be bracing to those who remember the project's promise of urban renewal when it was completed in 1962, to the design of urban planner Victor Gruen. According to the Wikipedia entry on Midtown, "Gruen was at the height of his influence when Midtown was completed and the project attracted international attention, including a nationally televised feature report on NBC-TV's Huntley-Brinkley newscast the night of its opening in April 1962. City officials and planners from around the globe came to see Gruen's solution to the mid-century urban crisis. Midtown won several design awards." A Jewish refugee from Nazi occupied Vienna, Gruen said he arrived in America with "an architectural degree, eight dollars, and no English." He went from designing Fifth Avenue boutiques to a role as one of America's premier urban planners. Melding his insights into consumer psychology with a conviction that retail spaces could create communities, Gruen invented the shopping mall. He strove to bring the urbanity of his native Vienna and Europe to America, claiming the Milan Galleria was his model for the mall. In 2004, Malcolm Gladwell wrote in The New Yorker that "Victor Gruen may well have been the most influential architect of the twentieth century" for his creation of the pervasive archetype. Gruen's impact continues to be registered. Gladwell's appraisal followed on the publication of Jeffrey Hardwick's 2004 book, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. A decade ago, the media theorist and concept-coiner Douglas Rushkoff began popularizing the Gruen Transfer, also known as the Gruen Effect, by which shoppers are intentionally disoriented and distracted by the retail environment, so they'll lose focus and succumb to impulse buying. Since 2008, The Gruen Transfer has been the title of an Australian TV series on advertising. In 2009, Anette Baldauf and Katharina Weingartner released the documentary, The Gruen Effect: Victor Gruen and the Shopping Mall.

Photographed last week, Midtown Plaza's piecemeal demolition brings the look of a ship breaking yard to the skyline of Rochester, New York. The image may be bracing to those who remember the project's promise of urban renewal when it was completed in 1962, to the design of urban planner Victor Gruen. According to the Wikipedia entry on Midtown, "Gruen was at the height of his influence when Midtown was completed and the project attracted international attention, including a nationally televised feature report on NBC-TV's Huntley-Brinkley newscast the night of its opening in April 1962. City officials and planners from around the globe came to see Gruen's solution to the mid-century urban crisis. Midtown won several design awards." A Jewish refugee from Nazi occupied Vienna, Gruen said he arrived in America with "an architectural degree, eight dollars, and no English." He went from designing Fifth Avenue boutiques to a role as one of America's premier urban planners. Melding his insights into consumer psychology with a conviction that retail spaces could create communities, Gruen invented the shopping mall. He strove to bring the urbanity of his native Vienna and Europe to America, claiming the Milan Galleria was his model for the mall. In 2004, Malcolm Gladwell wrote in The New Yorker that "Victor Gruen may well have been the most influential architect of the twentieth century" for his creation of the pervasive archetype. Gruen's impact continues to be registered. Gladwell's appraisal followed on the publication of Jeffrey Hardwick's 2004 book, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. A decade ago, the media theorist and concept-coiner Douglas Rushkoff began popularizing the Gruen Transfer, also known as the Gruen Effect, by which shoppers are intentionally disoriented and distracted by the retail environment, so they'll lose focus and succumb to impulse buying. Since 2008, The Gruen Transfer has been the title of an Australian TV series on advertising. In 2009, Anette Baldauf and Katharina Weingartner released the documentary, The Gruen Effect: Victor Gruen and the Shopping Mall.  Midtown Plaza introduced the nation's first urban shopping mall, within a mixed-use megastructure. The project included 2,000 underground parking spaces, a 300-seat auditorium, and an office block with a hotel above (here shown disappearing). A restaurant projected from the base of the hotel element, providing dramatic views from what was Rochester's tallest building. Two skyways connected the complex to nearby office buildings. Gruen wrote, "It is our belief that there is much need for actual shopping centers - market places that are also centers of community and cultural activity." In its coverage of Midtown Plaza, Architectural Forum magazine quoted Gruen as saying, "We wanted to create a town square with urbane qualities. At the same time, the Plaza is important as a setting for cultural and social events - concerts, fashion shows, balls, and those activities which one connects with urban life." Gruen's formula for urban renewal included a downtown mall, ample parking, and a ring road to ease car access to parking. The ring road was adopted from his native Vienna. Gruen found one ready made in Rochester, whose residents may be stunned to learn that someone once saw Vienna's Ringstrasse in their unassuming Inner Loop. Despite its importance as an artifact of American urban planning, Midtown isn't the sort of project that gets preserved. The recent Cronocaos exhibition organized by Rem Koolhaas and his OMA partner Shohei Shigematsu, accused preservationists of scenographically cherry picking what to preserve and whitewashing urban evolution. In his review of the show for the New York Times, Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote, "This phenomenon is coupled with another disturbing trend: the selective demolition of the most socially ambitious architecture of the 1960s and ’70s — the last period when architects were able to do large-scale public work. That style has been condemned as a monstrous expression of Modernism." Examples noted in the show included East Berlin's Palast der Republik and Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower. Koolhaas' own respect for ambitious mega-projects would seem sympathetic to Midtown Plaza, if malls weren't the essence of the air-conditioned and escalatored nowhere he's named "Junkspace."

Midtown Plaza introduced the nation's first urban shopping mall, within a mixed-use megastructure. The project included 2,000 underground parking spaces, a 300-seat auditorium, and an office block with a hotel above (here shown disappearing). A restaurant projected from the base of the hotel element, providing dramatic views from what was Rochester's tallest building. Two skyways connected the complex to nearby office buildings. Gruen wrote, "It is our belief that there is much need for actual shopping centers - market places that are also centers of community and cultural activity." In its coverage of Midtown Plaza, Architectural Forum magazine quoted Gruen as saying, "We wanted to create a town square with urbane qualities. At the same time, the Plaza is important as a setting for cultural and social events - concerts, fashion shows, balls, and those activities which one connects with urban life." Gruen's formula for urban renewal included a downtown mall, ample parking, and a ring road to ease car access to parking. The ring road was adopted from his native Vienna. Gruen found one ready made in Rochester, whose residents may be stunned to learn that someone once saw Vienna's Ringstrasse in their unassuming Inner Loop. Despite its importance as an artifact of American urban planning, Midtown isn't the sort of project that gets preserved. The recent Cronocaos exhibition organized by Rem Koolhaas and his OMA partner Shohei Shigematsu, accused preservationists of scenographically cherry picking what to preserve and whitewashing urban evolution. In his review of the show for the New York Times, Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote, "This phenomenon is coupled with another disturbing trend: the selective demolition of the most socially ambitious architecture of the 1960s and ’70s — the last period when architects were able to do large-scale public work. That style has been condemned as a monstrous expression of Modernism." Examples noted in the show included East Berlin's Palast der Republik and Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower. Koolhaas' own respect for ambitious mega-projects would seem sympathetic to Midtown Plaza, if malls weren't the essence of the air-conditioned and escalatored nowhere he's named "Junkspace."  In his 1964 book, The Heart of Our Cities: The Urban Crisis, Diagnosis and Cure, Gruen prominently featured Midtown Plaza, documenting its advertised social role with this newspaper photo of a high school dance on the floor of its shopping mall. Helped by a tailwind from the 1960s economic boom, Midtown was initially an undeniable success. Within twenty years, it proved to have been a mere eddy against the inexorable tide of white flight and sprawl fueled by the more common suburban version of the mall. Writing in the 2002 book, The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, contributor Sze Tsung Leong writes: "Victor Gruen, widely acknowledged as the inventor of the shopping mall, was, in the end, not interested in shopping. Instead, the shopping mall was a vehicle toward his real ambition: to redefine the contemporary city. For Gruen, the mall was the new city." Leong quotes Gruen's 1960 book, Shopping Towns USA: "By affording opportunities for social life and recreation in a protected pedestrian environment, by incorporating civic and educational facilities, shopping centers can fill an existing void. They can provide the needed place and opportunity for participation in modern community life that the ancient Greek Agora, the Medieval Market Place and our Town Squares provided in the past." Leong observes, "At he same time that Victor Gruen was configuring the mall to provide civic functions, he was also envisioning the suburban shopping mall as a model for downtown revitalization." Midtown Plaza would be the first implementation of this vision. Although the shopping mall would indeed serve a social role, particularly among teenagers, the idea that it would be the new Agora now ranks with early hopes that TV would be educational.

In his 1964 book, The Heart of Our Cities: The Urban Crisis, Diagnosis and Cure, Gruen prominently featured Midtown Plaza, documenting its advertised social role with this newspaper photo of a high school dance on the floor of its shopping mall. Helped by a tailwind from the 1960s economic boom, Midtown was initially an undeniable success. Within twenty years, it proved to have been a mere eddy against the inexorable tide of white flight and sprawl fueled by the more common suburban version of the mall. Writing in the 2002 book, The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, contributor Sze Tsung Leong writes: "Victor Gruen, widely acknowledged as the inventor of the shopping mall, was, in the end, not interested in shopping. Instead, the shopping mall was a vehicle toward his real ambition: to redefine the contemporary city. For Gruen, the mall was the new city." Leong quotes Gruen's 1960 book, Shopping Towns USA: "By affording opportunities for social life and recreation in a protected pedestrian environment, by incorporating civic and educational facilities, shopping centers can fill an existing void. They can provide the needed place and opportunity for participation in modern community life that the ancient Greek Agora, the Medieval Market Place and our Town Squares provided in the past." Leong observes, "At he same time that Victor Gruen was configuring the mall to provide civic functions, he was also envisioning the suburban shopping mall as a model for downtown revitalization." Midtown Plaza would be the first implementation of this vision. Although the shopping mall would indeed serve a social role, particularly among teenagers, the idea that it would be the new Agora now ranks with early hopes that TV would be educational.  Banking on a single project to revitalize a city might seem quaint but for the recent example of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which so successfully jump-started the Basque town's economy as to give urbanism the Bilbao Effect. (Photo: User:MykReeve.) Gehry worked for Victor Gruen in the 1950s when Midtown Plaza was being designed and is said to have been greatly influenced by his views on city planning. It was during this time that Gehry changed his name from Goldberg as Gruen had changed his own from Grünbaum, immigrants self-inventing in American Gatz-to-Gatsby fashion. Early in his own practice, Gehry used his experience in Gruen's office to design several shopping malls including Santa Monica Place. In Bilbao, Gehry's building inverts Gruen's urban mall strategy, making culture a vehicle for commerce. The commercialization of museums has been much commented on, as their shops take up increasing amounts of space and multiple locations within, while sprouting external outposts with no museum attached at all.

Banking on a single project to revitalize a city might seem quaint but for the recent example of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which so successfully jump-started the Basque town's economy as to give urbanism the Bilbao Effect. (Photo: User:MykReeve.) Gehry worked for Victor Gruen in the 1950s when Midtown Plaza was being designed and is said to have been greatly influenced by his views on city planning. It was during this time that Gehry changed his name from Goldberg as Gruen had changed his own from Grünbaum, immigrants self-inventing in American Gatz-to-Gatsby fashion. Early in his own practice, Gehry used his experience in Gruen's office to design several shopping malls including Santa Monica Place. In Bilbao, Gehry's building inverts Gruen's urban mall strategy, making culture a vehicle for commerce. The commercialization of museums has been much commented on, as their shops take up increasing amounts of space and multiple locations within, while sprouting external outposts with no museum attached at all.  The 2001 Prada flagship store is the design of OMA, the architecture firm of Rem Koolhaas, another contributor to The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. The design seems to respond particularly to a post-Gruen world where shopping has been established as the answer to everything. According to OMA's website, the design is part of the firm's "ongoing research into shopping, arguably the last remaining form of public activity. . . . As museums, libraries, airports, hospitals, and schools become increasingly indistinguishable from shopping centres, their adoption of retail for survival has unleashed an enormous wave of commercial entrapment that has transformed museum-goers, researchers, travelers, patients, and students into customers. The result is a deadening loss of variety. What were once distinct activities no longer retain the uniqueness that gave them richness. What if the equation were reversed, so that customers were no longer identified as consumers, but recognized as researchers, students, patients, museum-goers? What if the shopping experience were not one of impoverishment, but of enrichment?" The Prada store's response is its dual-purpose central wave. OMA's website explains how it works: "On one side, the slope has steps – ostensibly for displaying shoes and accessories – that can be used as a seating area, facing a stage that unfolds from the other side of the wave. The store thus becomes a venue for film screenings, performances, and lectures." An impressive amount of valuable retail space was dedicated to this conceit, which appears mainly to justify the Koolhaas trademark of blended floor levels. Asked about the frequency of the stage's use, the store's management referred the question to Prada's corporate office which referred it in turn to its public relations department, approachable only by fax, and so far unresponsive. Victor Gruen had ruefully learned decades earlier that when push comes to shove between commerce and culture, commerce wins. Prada's entire SoHo setting has itself lost most of its distinctive urban character in its transition to an outdoor shopping mall dominated by national chains. Victor Gruen ultimately regretted the impact of the mall archetype he had created. According to Jeffrey Hardwick's Mall Maker, in a 1978 London speech he criticized Americans for perverting his ideas, saying "I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments." Hardwick writes that at seventy-five, "Gruen had reached the end of his faith in the power of architectural solutions," continuing that "In Gruen's opinion, the shopping center had become focused solely on its primary goal of promoting retail and had abandoned its possible role in creating new communities." His suburban malls had not only failed to bear civic fruit, but had helped kill the city itself, while putting the American car culture he despised on steroids. Mall Maker quotes one of Gruen's business partners, Karl Van Leuven, describing an early 1950s visit with Gruen to the site of their gigantic Northland mall outside Detroit: "'There were all those monstrous earth moving machines pushing and shoving and changing the face of some 200 acres,' he recalled. After watching this impressive effort, Gruen turned to Van Leuven and softly said, 'My God but we've got a lot of nerve.'" Given the greater impact, on Detroit and the American city and landscape, Oppenheimer's "destroyer of worlds" moment comes to mind. The genie was out of the bottle. In a 1994 essay, "What Ever Happened to Urbanism?" Rem Koolhaas described an out of control urbanism that will be replaced by "an ideology: to accept what exists. We were making sand castles. Now we swim in the sea that swept them away." Many see only resignation in his stance, but old-school urbanism can be seen washing away this month on the Rochester skyline.

The 2001 Prada flagship store is the design of OMA, the architecture firm of Rem Koolhaas, another contributor to The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. The design seems to respond particularly to a post-Gruen world where shopping has been established as the answer to everything. According to OMA's website, the design is part of the firm's "ongoing research into shopping, arguably the last remaining form of public activity. . . . As museums, libraries, airports, hospitals, and schools become increasingly indistinguishable from shopping centres, their adoption of retail for survival has unleashed an enormous wave of commercial entrapment that has transformed museum-goers, researchers, travelers, patients, and students into customers. The result is a deadening loss of variety. What were once distinct activities no longer retain the uniqueness that gave them richness. What if the equation were reversed, so that customers were no longer identified as consumers, but recognized as researchers, students, patients, museum-goers? What if the shopping experience were not one of impoverishment, but of enrichment?" The Prada store's response is its dual-purpose central wave. OMA's website explains how it works: "On one side, the slope has steps – ostensibly for displaying shoes and accessories – that can be used as a seating area, facing a stage that unfolds from the other side of the wave. The store thus becomes a venue for film screenings, performances, and lectures." An impressive amount of valuable retail space was dedicated to this conceit, which appears mainly to justify the Koolhaas trademark of blended floor levels. Asked about the frequency of the stage's use, the store's management referred the question to Prada's corporate office which referred it in turn to its public relations department, approachable only by fax, and so far unresponsive. Victor Gruen had ruefully learned decades earlier that when push comes to shove between commerce and culture, commerce wins. Prada's entire SoHo setting has itself lost most of its distinctive urban character in its transition to an outdoor shopping mall dominated by national chains. Victor Gruen ultimately regretted the impact of the mall archetype he had created. According to Jeffrey Hardwick's Mall Maker, in a 1978 London speech he criticized Americans for perverting his ideas, saying "I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments." Hardwick writes that at seventy-five, "Gruen had reached the end of his faith in the power of architectural solutions," continuing that "In Gruen's opinion, the shopping center had become focused solely on its primary goal of promoting retail and had abandoned its possible role in creating new communities." His suburban malls had not only failed to bear civic fruit, but had helped kill the city itself, while putting the American car culture he despised on steroids. Mall Maker quotes one of Gruen's business partners, Karl Van Leuven, describing an early 1950s visit with Gruen to the site of their gigantic Northland mall outside Detroit: "'There were all those monstrous earth moving machines pushing and shoving and changing the face of some 200 acres,' he recalled. After watching this impressive effort, Gruen turned to Van Leuven and softly said, 'My God but we've got a lot of nerve.'" Given the greater impact, on Detroit and the American city and landscape, Oppenheimer's "destroyer of worlds" moment comes to mind. The genie was out of the bottle. In a 1994 essay, "What Ever Happened to Urbanism?" Rem Koolhaas described an out of control urbanism that will be replaced by "an ideology: to accept what exists. We were making sand castles. Now we swim in the sea that swept them away." Many see only resignation in his stance, but old-school urbanism can be seen washing away this month on the Rochester skyline.

Windowflage, part 4

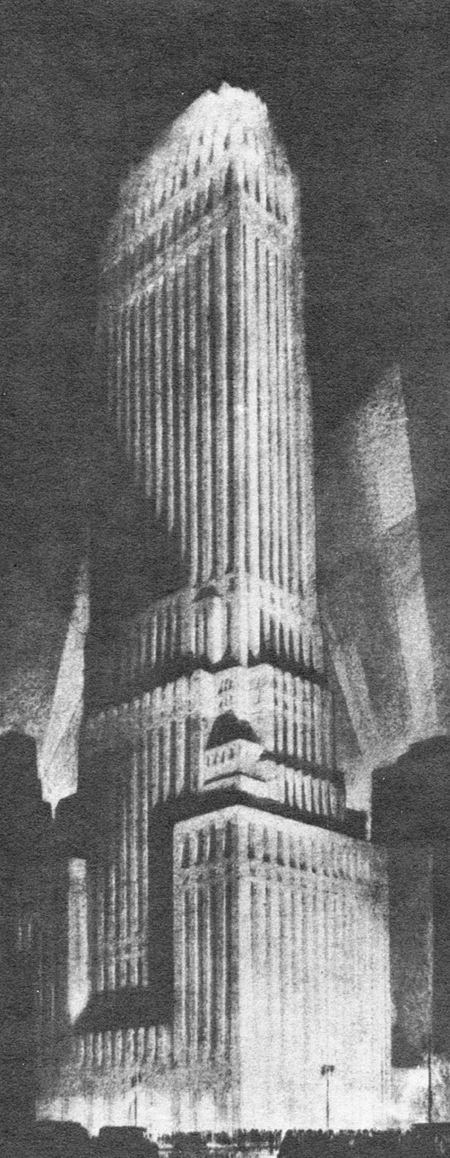

Linked Hybrid, a Beijing complex designed by Steven Holl, was completed last year. As with his Simmons Hall dormitory at MIT, Holl sets windows deeply into a uniform and pervasive grid, camouflaging them as dimples in an enveloping waffle texture that's applied like shrink-wrap. He so accentuates the window grid that it takes on the geometric purity of abstract sculpture. Like many other architects today, Holl hides his windows in plain sight. Unlike so many others, he does this by embracing the grid rather than fleeing it.

Linked Hybrid, a Beijing complex designed by Steven Holl, was completed last year. As with his Simmons Hall dormitory at MIT, Holl sets windows deeply into a uniform and pervasive grid, camouflaging them as dimples in an enveloping waffle texture that's applied like shrink-wrap. He so accentuates the window grid that it takes on the geometric purity of abstract sculpture. Like many other architects today, Holl hides his windows in plain sight. Unlike so many others, he does this by embracing the grid rather than fleeing it.

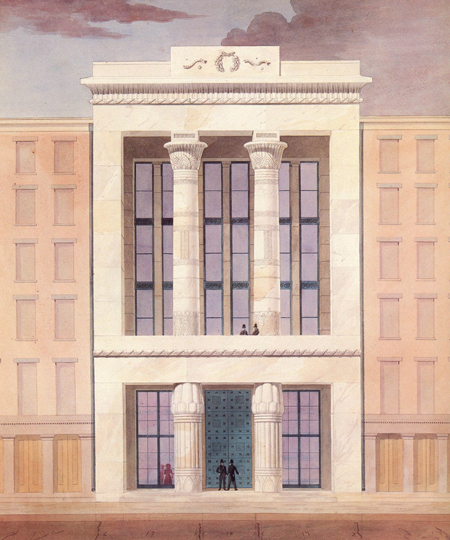

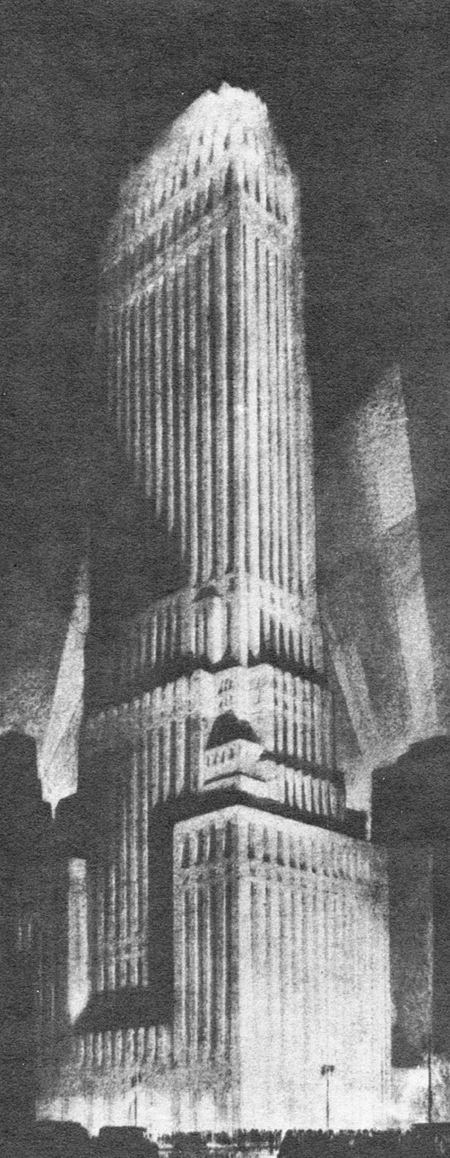

Georgia O'Keefe's 1927 painting, Radiator Building - Night, New York, shows Raymond Hood's tower at an hour when its dark window openings can't disappear into its black brick façade. The randomness of a city's lit windows at night violates the tyranny of the grid with chance, mystery and individual volition. In recent years, architects have brought this defiance of regimentation into daylight.

Georgia O'Keefe's 1927 painting, Radiator Building - Night, New York, shows Raymond Hood's tower at an hour when its dark window openings can't disappear into its black brick façade. The randomness of a city's lit windows at night violates the tyranny of the grid with chance, mystery and individual volition. In recent years, architects have brought this defiance of regimentation into daylight.

Forty years ahead of its time, an otherwise anonymous 1963 hotel on West 57th Street willfully offsets windows from their expected vertical alignment. The effect is so successful at destroying the usual window grid that the building at first appears to defy structural logic. Only on close inspection does it become apparent that there are still continuous vertical paths for the exterior wall's columns, and that windows are merely jiggled left and right within conventional column bays. While the building's countless identical windows are no less visible and repetitive, they are less suggestive of coercion than windows in a grid, and seem to belong to the liberated realm of surface decoration. Gridding is so much a part of the Gestalt of urban windows that to take them out of alignment camouflages them, effectively hiding them in plain sight.

Forty years ahead of its time, an otherwise anonymous 1963 hotel on West 57th Street willfully offsets windows from their expected vertical alignment. The effect is so successful at destroying the usual window grid that the building at first appears to defy structural logic. Only on close inspection does it become apparent that there are still continuous vertical paths for the exterior wall's columns, and that windows are merely jiggled left and right within conventional column bays. While the building's countless identical windows are no less visible and repetitive, they are less suggestive of coercion than windows in a grid, and seem to belong to the liberated realm of surface decoration. Gridding is so much a part of the Gestalt of urban windows that to take them out of alignment camouflages them, effectively hiding them in plain sight.

SHoP Architects' critically acclaimed Porter House condominium at West 15th Street and Ninth Avenue, completed in 2003, adapted and added onto a 1905 warehouse. The addition roughly matches the bulk of the original building, a key to its success in the role of mirror-opposite. By contrasting itself in every possible way, even offsetting itself from the old building's footprint, the addition leaves the integrity of the original perfectly readable. Among its points of departure, the addition sets its windows free of the grid and varies their width. They are closely enough spaced not to disfavor any of the identical stacked floor plans within on any given floor.

SHoP Architects' critically acclaimed Porter House condominium at West 15th Street and Ninth Avenue, completed in 2003, adapted and added onto a 1905 warehouse. The addition roughly matches the bulk of the original building, a key to its success in the role of mirror-opposite. By contrasting itself in every possible way, even offsetting itself from the old building's footprint, the addition leaves the integrity of the original perfectly readable. Among its points of departure, the addition sets its windows free of the grid and varies their width. They are closely enough spaced not to disfavor any of the identical stacked floor plans within on any given floor.

SHop takes no chances in pusuit of the romantically staggered lit windows of Georgia O'keefe's Radiator Building portrayal. Fixtures built into the addition's face insure a balanced distribution of haphazard light sources, regardless of occupants' contributions.

SHop takes no chances in pusuit of the romantically staggered lit windows of Georgia O'keefe's Radiator Building portrayal. Fixtures built into the addition's face insure a balanced distribution of haphazard light sources, regardless of occupants' contributions.

Polshek Partnership's Standard Hotel, completed last year, straddles the High Line near Washington and West 13th Streets. The building's floor-to-ceiling glass makes the rooms' curtains a facade-determining feature. By day, they contribute the shifting randomness and vitality that variations in artificial lighting typically provide at night.

Polshek Partnership's Standard Hotel, completed last year, straddles the High Line near Washington and West 13th Streets. The building's floor-to-ceiling glass makes the rooms' curtains a facade-determining feature. By day, they contribute the shifting randomness and vitality that variations in artificial lighting typically provide at night.

The Standard Hotel's jiggled window pattern, echoing that of the 1963 hotel pictured above, further defuses the deadening effect of the grid and suggests the decorative freedom of textile design.

The Standard Hotel's jiggled window pattern, echoing that of the 1963 hotel pictured above, further defuses the deadening effect of the grid and suggests the decorative freedom of textile design.

One Ten 3rd, a condominium at 110 Third Avenue, was designed by Greenberg Farrow and completed in 2007. Listing the building's pros and cons, CityRealty cites its "unusual fenestration pattern" as a "con," while New York magazine's Justin Davidson called the building an "impressively awful tower, full of fussy fenestration and clutter." These assessments overlook how efficiently the design avoids gridlock by simply varying the color of the panels covering columns. This variation, within a limited color range, also blends with the predictable chaos of individual owners' window treatments to produce a painterly effect.

One Ten 3rd, a condominium at 110 Third Avenue, was designed by Greenberg Farrow and completed in 2007. Listing the building's pros and cons, CityRealty cites its "unusual fenestration pattern" as a "con," while New York magazine's Justin Davidson called the building an "impressively awful tower, full of fussy fenestration and clutter." These assessments overlook how efficiently the design avoids gridlock by simply varying the color of the panels covering columns. This variation, within a limited color range, also blends with the predictable chaos of individual owners' window treatments to produce a painterly effect.

SOM's addition to John Jay College is approaching completion at Eleventh Avenue between 58th and 59th Streets. Glass units with fritted glass dots in varying densities create patterns that override the framing grid.

SOM's addition to John Jay College is approaching completion at Eleventh Avenue between 58th and 59th Streets. Glass units with fritted glass dots in varying densities create patterns that override the framing grid.

Based on paint manufacturers' color sample chips, Peter Wegner's 2001 painting, 49 Greys, might have inspired SOM's façade at John Jay College. The painting resonates with current architecture's use of the grid as a point of departure for vibrant destinations.

Based on paint manufacturers' color sample chips, Peter Wegner's 2001 painting, 49 Greys, might have inspired SOM's façade at John Jay College. The painting resonates with current architecture's use of the grid as a point of departure for vibrant destinations.

The Zollverein School of Design in Essen, Germany, by SANAA, was completed in 2006. (photo: Michael Hoefner, CC/SA) It practices a different kind of windowflage from the same firm's mesh-encased New Museum of Contemporary Art on the Bowery. Here, windows are set free of the familiar grid in all directions and even deny its possibility by their varied sizes. While emphatically expressed, the windows contribute to, rather than detract from, the overall building as sculpture.