House Rules

House Rules - Afterword

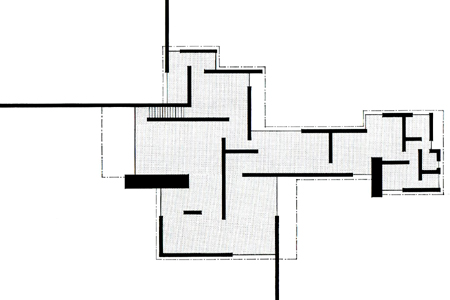

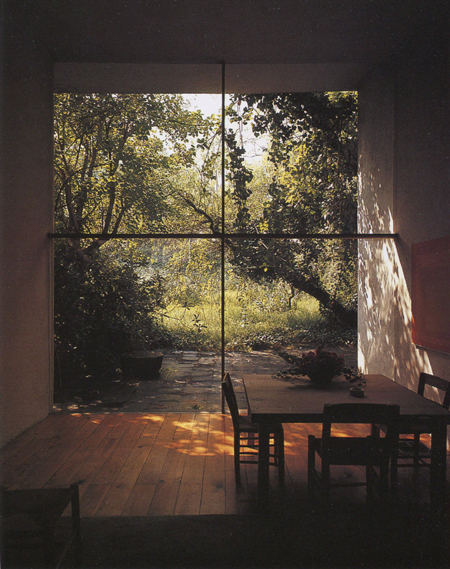

Shinichi Ogawa's 2002 Abstract House could illustrate any of the ten House Rules. It demonstrates not just their compatibility, but their potential to enhance each other. In exploiting the strategies on which the rules are based, this modest house efficiently summons spatial luxury and an undistracted connection to nature from an ordinary site.

Shinichi Ogawa's 2002 Abstract House could illustrate any of the ten House Rules. It demonstrates not just their compatibility, but their potential to enhance each other. In exploiting the strategies on which the rules are based, this modest house efficiently summons spatial luxury and an undistracted connection to nature from an ordinary site.

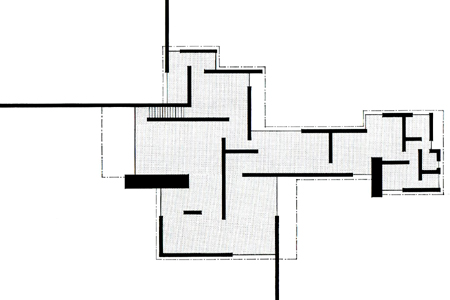

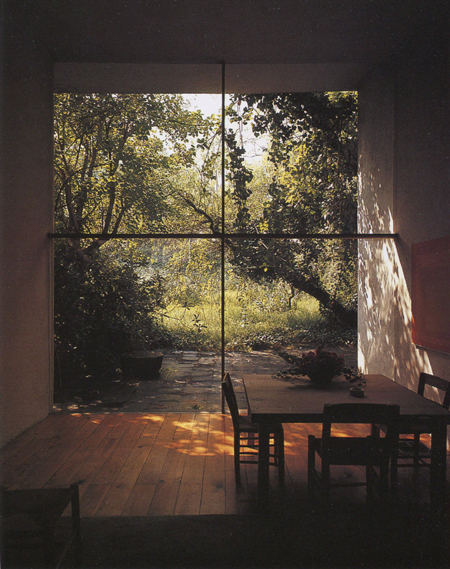

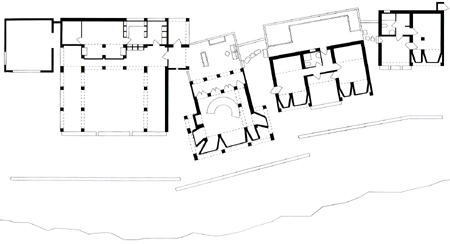

Ogawa's floor plan successfully transplants lessons from Mies van der Rohe's bucolic Farnsworth House into Japan's Onomichi City. Its long side walls extend into the outdoors to embrace a small court at each end. The courtyard walls provide privacy from nearby houses and block street level distraction. The design's minimalism gives the tiny courts a disproportionate impact, letting nature and atmospheric conditions set the tone of the house in a more dynamic and affecting way than any decorating scheme; not as pervasively as in a glass-box house but with much bigger bang for the pane. (Pivoting panels at either end of the service core can be closed to seal off the more private zone, at right above, or stand open to replicate the Farnsworth House's spatial loop.)

The idea for House Rules grew out of a conversation with a couple who asked for a critique of a plan they had found and liked in a book of house plans. From the perspective of an architect, the design was disappointing but it was hard to say why. Singling out shortcomings didn't sum up what was wrong with it and only seemed nitpicking. The problem wasn't so much with what the plan was, but all that it wasn't. A copy of James Ackerman's book on Palladio was within reach, and next we were looking at a plan of the Villa Foscari: "See how both the house and its individual rooms are all perfect shapes, as if they were designed at once, and nothing feels like leftover space?" What would be House Rule 3 was born. The rules presuppose small houses and reflect personal preferences, but a case can be made for their validity on both counts. Small houses make sense for sustainability and in response to America's soaring percentage of one- and two-person households, which are now the national norm. Houses designed for such small households are freed from substantial privacy and partitioning needs, and can pursue exciting spatial opportunities in their place, much as sports cars are freed from back seats and sensible hardtops. Small houses can also bring custom design into reach. Lending practices require more money to be spent up front on land acquisition and construction for self-built homes as opposed to purchase of ready-made development houses. Economic necessity funnels the vast majority of new home buyers into speculative tract houses that aren't based on what most of us want, but on marketing assumptions aimed at maximizing profits across the boards. Developers seem to take Frank Lloyd Wright's view of the American house - a box full of boxes with holes punched in it for windows – as a description of what Americans really want and a recipe for sales success rather than a complaint. If Americans were more willing to live in compact, affordable houses, many more would be in a position to finance custom designs. They'd be living in smaller but better-fitting homes, and the typical American house would look very little as it now does. The House Rules aim to encourage this alternative by optimizing the quality of space and experience in such houses, adding value through inexpensive or cost-free design decisions. Beyond economic considerations, whatever validity the House Rules may claim lies in the merit of the great houses from which they're derived. It became clear in assembling them that individual rules could not only be illustrated by the majority of iconic modern houses, but that most of the houses used as examples embodied most of the rules. The House Rules are an introduction to the possibilities that lie beyond developer housing. They aim to get more Americans into houses designed specifically for them by an architect. The rules aren't meant as a substitute for an architect, but a prelude to a conversation with one.House Rules - Afterword

Shinichi Ogawa's 2002 Abstract House could illustrate any of the ten House Rules. It demonstrates not just their compatibility, but their potential to enhance each other. In exploiting the strategies on which the rules are based, this modest house efficiently summons spatial luxury and an undistracted connection to nature from an ordinary site.

Shinichi Ogawa's 2002 Abstract House could illustrate any of the ten House Rules. It demonstrates not just their compatibility, but their potential to enhance each other. In exploiting the strategies on which the rules are based, this modest house efficiently summons spatial luxury and an undistracted connection to nature from an ordinary site.

Ogawa's floor plan successfully transplants lessons from Mies van der Rohe's bucolic Farnsworth House into Japan's Onomichi City. Its long side walls extend into the outdoors to embrace a small court at each end. The courtyard walls provide privacy from nearby houses and block street level distraction. The design's minimalism gives the tiny courts a disproportionate impact, letting nature and atmospheric conditions set the tone of the house in a more dynamic and affecting way than any decorating scheme; not as pervasively as in a glass-box house but with much bigger bang for the pane. (Pivoting panels at either end of the service core can be closed to seal off the more private zone, at right above, or stand open to replicate the Farnsworth House's spatial loop.)

The idea for House Rules grew out of a conversation with a couple who asked for a critique of a plan they had found and liked in a book of house plans. From the perspective of an architect, the design was disappointing but it was hard to say why. Singling out shortcomings didn't sum up what was wrong with it and only seemed nitpicking. The problem wasn't so much with what the plan was, but all that it wasn't. A copy of James Ackerman's book on Palladio was within reach, and next we were looking at a plan of the Villa Foscari: "See how both the house and its individual rooms are all perfect shapes, as if they were designed at once, and nothing feels like leftover space?" What would be House Rule 3 was born. The rules presuppose small houses and reflect personal preferences, but a case can be made for their validity on both counts. Small houses make sense for sustainability and in response to America's soaring percentage of one- and two-person households, which are now the national norm. Houses designed for such small households are freed from substantial privacy and partitioning needs, and can pursue exciting spatial opportunities in their place, much as sports cars are freed from back seats and sensible hardtops. Small houses can also bring custom design into reach. Lending practices require more money to be spent up front on land acquisition and construction for self-built homes as opposed to purchase of ready-made development houses. Economic necessity funnels the vast majority of new home buyers into speculative tract houses that aren't based on what most of us want, but on marketing assumptions aimed at maximizing profits across the boards. Developers seem to take Frank Lloyd Wright's view of the American house - a box full of boxes with holes punched in it for windows – as a description of what Americans really want and a recipe for sales success rather than a complaint. If Americans were more willing to live in compact, affordable houses, many more would be in a position to finance custom designs. They'd be living in smaller but better-fitting homes, and the typical American house would look very little as it now does. The House Rules aim to encourage this alternative by optimizing the quality of space and experience in such houses, adding value through inexpensive or cost-free design decisions. Beyond economic considerations, whatever validity the House Rules may claim lies in the merit of the great houses from which they're derived. It became clear in assembling them that individual rules could not only be illustrated by the majority of iconic modern houses, but that most of the houses used as examples embodied most of the rules. The House Rules are an introduction to the possibilities that lie beyond developer housing. They aim to get more Americans into houses designed specifically for them by an architect. The rules aren't meant as a substitute for an architect, but a prelude to a conversation with one.House Rule 10 - Embrace Inconvenience

“I'd rather live in the nave of Chartres Cathedral and go out of doors to the john,” Philip Johnson told his architecture students. His sentiment will resonate with anyone who's ever stood in a meadow, greenhouse, park pavilion, industrial ruin or other non-house and impulsively felt “I want to live here.” While such fantasies are soon quashed by practical priorities, they offer valid insights.

“I'd rather live in the nave of Chartres Cathedral and go out of doors to the john,” Philip Johnson told his architecture students. His sentiment will resonate with anyone who's ever stood in a meadow, greenhouse, park pavilion, industrial ruin or other non-house and impulsively felt “I want to live here.” While such fantasies are soon quashed by practical priorities, they offer valid insights.

Johnson took what he felt under Chartres' forest of branching columns and put something of it into his Glass House, which is visually contained not by its clear walls but the tree-vaulted outdoors. His house adds indoor plumbing but very little else in the way of conveniences, focusing instead on the undistracted enjoyment of space. This bargain served Johnson well, and the Glass House was a great source of joy for the rest of his long life.

Johnson's wish to sleep in a cathedral recalls both Holly Golightly's free-spirited preference for breakfast at Tiffany's and Frank Lloyd Wright's heedless call, “Give me the luxuries of life and I will willingly do without the necessities.” Wright in turn was watering down Dorothy Parker's version, by which he more closely lived: “Take care of the luxuries and the necessities will take care of themselves.” The architectural grandaddy of such quotes belongs to Vitruvius, who said - via Sir Henry Wotton's translation - "Well-building hath three conditions: commoditie, firmeness and delight." Take away firmness (structural integrity) as a given, and you have commodity (practicality) vying for turf with delight. Or perhaps more often, responsiveness to practical needs standing in for the rarer resource of vision.

The practicality-vs-pleasure rivalry is certainly about more than just buildings, suggesting as it does the Big Question, “what's it all about?” Anthony Burgess succinctly took the dichotomy into philosophical territory in his 1960 novel, The Doctor is Sick. Its hospitalized protagonist quotes a line of verse to an unappreciative radiologist who responds, “I don't go in much for poetry." When he asks whether she thinks it's better to be a radiologist than a poet, she replies, "Oh yes. . . . After all, we save lives, don't we?" He then asks, "What's the purpose of saving lives? What do you want people to live for?"

Are we here to perpetuate the human race toward some unknown but presumably significant end? Or to enjoy it in the here and now, assuming our capacity to do so may just be that end? Should our houses be machines streamlined for raising the next generation, so it can raise the next, or are we better off seizing the day and building for pleasure? While Vitruvius' recipe calls for some of each, you'd never know it from the great majority of today's houses. They cram in convenience until there's no room left for delight.

This can be blamed on the business of housebuilding, or homebuilding as it's always called by its ever market-vigilant practitioners. Comfort and convenience are easy to package: lots of bathrooms, a master bedroom suite with a walk-in closet, wrap-around kitchens entered from multi-car garages, and so on. Even appliance brands get billing in real estate ads, with marketing analysts advising on their selection. Alternative qualities that might make a house an exciting place for a particular type of person or a specific site are too hard to define. There's no reassuring track record of profits for anything but the equivalent of top-40 radio. Offering anything else entails the risk of failure to sell, and the developer-built houses occupied by most Americans are nothing if not fearful. As with people, the fear in such houses can be read in their conformity.

The marketing shorthand of developer houses - "3,000 SF, 4 BR, 2-1/2 BA" - places quantity over quality and creates a self-perpetuating value system. Zoning ordinances then codify conventions, insisting on minimum square footages, attached garages, pitched roofs, front doors, full basements and so on. It's hard to tell whether these criteria show a greater fear of squatters' shacks or anything an imaginative architect would design. The canned ingredients left to the cook are like the railroading verbal cliches George Orwell deplored in his essay, "Politics and the English Language," which he saw as:

Johnson took what he felt under Chartres' forest of branching columns and put something of it into his Glass House, which is visually contained not by its clear walls but the tree-vaulted outdoors. His house adds indoor plumbing but very little else in the way of conveniences, focusing instead on the undistracted enjoyment of space. This bargain served Johnson well, and the Glass House was a great source of joy for the rest of his long life.

Johnson's wish to sleep in a cathedral recalls both Holly Golightly's free-spirited preference for breakfast at Tiffany's and Frank Lloyd Wright's heedless call, “Give me the luxuries of life and I will willingly do without the necessities.” Wright in turn was watering down Dorothy Parker's version, by which he more closely lived: “Take care of the luxuries and the necessities will take care of themselves.” The architectural grandaddy of such quotes belongs to Vitruvius, who said - via Sir Henry Wotton's translation - "Well-building hath three conditions: commoditie, firmeness and delight." Take away firmness (structural integrity) as a given, and you have commodity (practicality) vying for turf with delight. Or perhaps more often, responsiveness to practical needs standing in for the rarer resource of vision.

The practicality-vs-pleasure rivalry is certainly about more than just buildings, suggesting as it does the Big Question, “what's it all about?” Anthony Burgess succinctly took the dichotomy into philosophical territory in his 1960 novel, The Doctor is Sick. Its hospitalized protagonist quotes a line of verse to an unappreciative radiologist who responds, “I don't go in much for poetry." When he asks whether she thinks it's better to be a radiologist than a poet, she replies, "Oh yes. . . . After all, we save lives, don't we?" He then asks, "What's the purpose of saving lives? What do you want people to live for?"

Are we here to perpetuate the human race toward some unknown but presumably significant end? Or to enjoy it in the here and now, assuming our capacity to do so may just be that end? Should our houses be machines streamlined for raising the next generation, so it can raise the next, or are we better off seizing the day and building for pleasure? While Vitruvius' recipe calls for some of each, you'd never know it from the great majority of today's houses. They cram in convenience until there's no room left for delight.

This can be blamed on the business of housebuilding, or homebuilding as it's always called by its ever market-vigilant practitioners. Comfort and convenience are easy to package: lots of bathrooms, a master bedroom suite with a walk-in closet, wrap-around kitchens entered from multi-car garages, and so on. Even appliance brands get billing in real estate ads, with marketing analysts advising on their selection. Alternative qualities that might make a house an exciting place for a particular type of person or a specific site are too hard to define. There's no reassuring track record of profits for anything but the equivalent of top-40 radio. Offering anything else entails the risk of failure to sell, and the developer-built houses occupied by most Americans are nothing if not fearful. As with people, the fear in such houses can be read in their conformity.

The marketing shorthand of developer houses - "3,000 SF, 4 BR, 2-1/2 BA" - places quantity over quality and creates a self-perpetuating value system. Zoning ordinances then codify conventions, insisting on minimum square footages, attached garages, pitched roofs, front doors, full basements and so on. It's hard to tell whether these criteria show a greater fear of squatters' shacks or anything an imaginative architect would design. The canned ingredients left to the cook are like the railroading verbal cliches George Orwell deplored in his essay, "Politics and the English Language," which he saw as:

rushing in to do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one's meaning as clear as one can through pictures or sensations. Afterwards one can choose - not merely accept - the phrases that will best cover the meaning . . .

Pre-verbal and true to self, this fluid thought process corresponds to the intuitive design phase Louis Kahn championed to his students. As noted by David B. Brownlee (in Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture, 1991), Kahn was taking a page from his own education: "His emphasis on what he had come to call 'form,' the inherent essence that an architect had to discern in an architectural program before it was contaminated by practical considerations, was related to the Beaux-Arts emphasis on the preliminary, instinctive esquisse Glenn Murcutt's 1996-98 Fletcher-Page House has huge sliding glass doors that open to transform its living spaces into a porch. “I have a great desire to make a building which is just a big veranda,” Murcutt has said. Envisioning such a building as his house, he adds: “For myself, for my security at night, I would like to have

Glenn Murcutt's 1996-98 Fletcher-Page House has huge sliding glass doors that open to transform its living spaces into a porch. “I have a great desire to make a building which is just a big veranda,” Murcutt has said. Envisioning such a building as his house, he adds: “For myself, for my security at night, I would like to have  Koh Kitayama's 1994 F3 House uses a ready-made greenhouse to enclose a garage/party-space and a small elevated box that accommodates private living functions. The transparent greenhouse envelope might be seen as a variation on Glenn Murcutt's house-as-veranda, while its opaque interior box answers his wish for a secure one-room nocturnal retreat. The F3 House demonstrates what's possible when sensations replace established room types as generators of a house design.

Koh Kitayama's 1994 F3 House uses a ready-made greenhouse to enclose a garage/party-space and a small elevated box that accommodates private living functions. The transparent greenhouse envelope might be seen as a variation on Glenn Murcutt's house-as-veranda, while its opaque interior box answers his wish for a secure one-room nocturnal retreat. The F3 House demonstrates what's possible when sensations replace established room types as generators of a house design.

What Kitayama's F3 House sacrifices in conventional comfort and convenience, it makes up for in delight. The particular bargain it strikes may not suit everyone, but the bachelor who commissioned it probably wouldn't have a hard time finding a like-minded buyer if he chose to sell it. An interest and cars and parties might not even be required, given the broad appeal of a return to life under the sky's blue dome.

If design fantasy is to lead to anything more than jacuzzis and home theaters, it has to go beyond comfort. It must trade such "commodity" for the true delight of reconnection with life's fundamentals and the joy that automatically comes of being reminded we're alive. As blandest suburbia proves, unchecked convenience chokes out life. It reminds us of Thoreau, turning his back on the comfort of town "to front only the essential facts of life," and of the ardent hearted Huck Finn's farewell: "I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can't stand it. I been there before." Huck wasn't going to stand for a life choreographed by room names. He'd take the primal joy of his most basic condition, as a free body in space.

Rule 10 is to embrace inconvenience.

What Kitayama's F3 House sacrifices in conventional comfort and convenience, it makes up for in delight. The particular bargain it strikes may not suit everyone, but the bachelor who commissioned it probably wouldn't have a hard time finding a like-minded buyer if he chose to sell it. An interest and cars and parties might not even be required, given the broad appeal of a return to life under the sky's blue dome.

If design fantasy is to lead to anything more than jacuzzis and home theaters, it has to go beyond comfort. It must trade such "commodity" for the true delight of reconnection with life's fundamentals and the joy that automatically comes of being reminded we're alive. As blandest suburbia proves, unchecked convenience chokes out life. It reminds us of Thoreau, turning his back on the comfort of town "to front only the essential facts of life," and of the ardent hearted Huck Finn's farewell: "I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can't stand it. I been there before." Huck wasn't going to stand for a life choreographed by room names. He'd take the primal joy of his most basic condition, as a free body in space.

Rule 10 is to embrace inconvenience.

Pay attention to any place that ignites passion and take home its fire. A house that's based only on practical decisions and fears of missteps will never be more than sensible and timid. Too much comfort and convenience insulate people from life and its greatest and simplest pleasures. Design a house not just to support life, but to make living worthwhile.

Continue to House Rules Afterword

Pay attention to any place that ignites passion and take home its fire. A house that's based only on practical decisions and fears of missteps will never be more than sensible and timid. Too much comfort and convenience insulate people from life and its greatest and simplest pleasures. Design a house not just to support life, but to make living worthwhile.

Continue to House Rules AfterwordHouse Rule 10 - Embrace Inconvenience

“I'd rather live in the nave of Chartres Cathedral and go out of doors to the john,” Philip Johnson told his architecture students. His sentiment will resonate with anyone who's ever stood in a meadow, greenhouse, park pavilion, industrial ruin or other non-house and impulsively felt “I want to live here.” While such fantasies are soon quashed by practical priorities, they offer valid insights.

“I'd rather live in the nave of Chartres Cathedral and go out of doors to the john,” Philip Johnson told his architecture students. His sentiment will resonate with anyone who's ever stood in a meadow, greenhouse, park pavilion, industrial ruin or other non-house and impulsively felt “I want to live here.” While such fantasies are soon quashed by practical priorities, they offer valid insights.

Johnson took what he felt under Chartres' forest of branching columns and put something of it into his Glass House, which is visually contained not by its clear walls but the tree-vaulted outdoors. His house adds indoor plumbing but very little else in the way of conveniences, focusing instead on the undistracted enjoyment of space. This bargain served Johnson well, and the Glass House was a great source of joy for the rest of his long life.

Johnson's wish to sleep in a cathedral recalls both Holly Golightly's free-spirited preference for breakfast at Tiffany's and Frank Lloyd Wright's heedless call, “Give me the luxuries of life and I will willingly do without the necessities.” Wright in turn was watering down Dorothy Parker's version, by which he more closely lived: “Take care of the luxuries and the necessities will take care of themselves.” The architectural grandaddy of such quotes belongs to Vitruvius, who said - via Sir Henry Wotton's translation - "Well-building hath three conditions: commoditie, firmeness and delight." Take away firmness (structural integrity) as a given, and you have commodity (practicality) vying for turf with delight. Or perhaps more often, responsiveness to practical needs standing in for the rarer resource of vision.

The practicality-vs-pleasure rivalry is certainly about more than just buildings, suggesting as it does the Big Question, “what's it all about?” Anthony Burgess succinctly took the dichotomy into philosophical territory in his 1960 novel, The Doctor is Sick. Its hospitalized protagonist quotes a line of verse to an unappreciative radiologist who responds, “I don't go in much for poetry." When he asks whether she thinks it's better to be a radiologist than a poet, she replies, "Oh yes. . . . After all, we save lives, don't we?" He then asks, "What's the purpose of saving lives? What do you want people to live for?"

Are we here to perpetuate the human race toward some unknown but presumably significant end? Or to enjoy it in the here and now, assuming our capacity to do so may just be that end? Should our houses be machines streamlined for raising the next generation, so it can raise the next, or are we better off seizing the day and building for pleasure? While Vitruvius' recipe calls for some of each, you'd never know it from the great majority of today's houses. They cram in convenience until there's no room left for delight.

This can be blamed on the business of housebuilding, or homebuilding as it's always called by its ever market-vigilant practitioners. Comfort and convenience are easy to package: lots of bathrooms, a master bedroom suite with a walk-in closet, wrap-around kitchens entered from multi-car garages, and so on. Even appliance brands get billing in real estate ads, with marketing analysts advising on their selection. Alternative qualities that might make a house an exciting place for a particular type of person or a specific site are too hard to define. There's no reassuring track record of profits for anything but the equivalent of top-40 radio. Offering anything else entails the risk of failure to sell, and the developer-built houses occupied by most Americans are nothing if not fearful. As with people, the fear in such houses can be read in their conformity.

The marketing shorthand of developer houses - "3,000 SF, 4 BR, 2-1/2 BA" - places quantity over quality and creates a self-perpetuating value system. Zoning ordinances then codify conventions, insisting on minimum square footages, attached garages, pitched roofs, front doors, full basements and so on. It's hard to tell whether these criteria show a greater fear of squatters' shacks or anything an imaginative architect would design. The canned ingredients left to the cook are like the railroading verbal cliches George Orwell deplored in his essay, "Politics and the English Language," which he saw as:

Johnson took what he felt under Chartres' forest of branching columns and put something of it into his Glass House, which is visually contained not by its clear walls but the tree-vaulted outdoors. His house adds indoor plumbing but very little else in the way of conveniences, focusing instead on the undistracted enjoyment of space. This bargain served Johnson well, and the Glass House was a great source of joy for the rest of his long life.

Johnson's wish to sleep in a cathedral recalls both Holly Golightly's free-spirited preference for breakfast at Tiffany's and Frank Lloyd Wright's heedless call, “Give me the luxuries of life and I will willingly do without the necessities.” Wright in turn was watering down Dorothy Parker's version, by which he more closely lived: “Take care of the luxuries and the necessities will take care of themselves.” The architectural grandaddy of such quotes belongs to Vitruvius, who said - via Sir Henry Wotton's translation - "Well-building hath three conditions: commoditie, firmeness and delight." Take away firmness (structural integrity) as a given, and you have commodity (practicality) vying for turf with delight. Or perhaps more often, responsiveness to practical needs standing in for the rarer resource of vision.

The practicality-vs-pleasure rivalry is certainly about more than just buildings, suggesting as it does the Big Question, “what's it all about?” Anthony Burgess succinctly took the dichotomy into philosophical territory in his 1960 novel, The Doctor is Sick. Its hospitalized protagonist quotes a line of verse to an unappreciative radiologist who responds, “I don't go in much for poetry." When he asks whether she thinks it's better to be a radiologist than a poet, she replies, "Oh yes. . . . After all, we save lives, don't we?" He then asks, "What's the purpose of saving lives? What do you want people to live for?"

Are we here to perpetuate the human race toward some unknown but presumably significant end? Or to enjoy it in the here and now, assuming our capacity to do so may just be that end? Should our houses be machines streamlined for raising the next generation, so it can raise the next, or are we better off seizing the day and building for pleasure? While Vitruvius' recipe calls for some of each, you'd never know it from the great majority of today's houses. They cram in convenience until there's no room left for delight.

This can be blamed on the business of housebuilding, or homebuilding as it's always called by its ever market-vigilant practitioners. Comfort and convenience are easy to package: lots of bathrooms, a master bedroom suite with a walk-in closet, wrap-around kitchens entered from multi-car garages, and so on. Even appliance brands get billing in real estate ads, with marketing analysts advising on their selection. Alternative qualities that might make a house an exciting place for a particular type of person or a specific site are too hard to define. There's no reassuring track record of profits for anything but the equivalent of top-40 radio. Offering anything else entails the risk of failure to sell, and the developer-built houses occupied by most Americans are nothing if not fearful. As with people, the fear in such houses can be read in their conformity.

The marketing shorthand of developer houses - "3,000 SF, 4 BR, 2-1/2 BA" - places quantity over quality and creates a self-perpetuating value system. Zoning ordinances then codify conventions, insisting on minimum square footages, attached garages, pitched roofs, front doors, full basements and so on. It's hard to tell whether these criteria show a greater fear of squatters' shacks or anything an imaginative architect would design. The canned ingredients left to the cook are like the railroading verbal cliches George Orwell deplored in his essay, "Politics and the English Language," which he saw as:

rushing in to do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one's meaning as clear as one can through pictures or sensations. Afterwards one can choose - not merely accept - the phrases that will best cover the meaning . . .

Pre-verbal and true to self, this fluid thought process corresponds to the intuitive design phase Louis Kahn championed to his students. As noted by David B. Brownlee (in Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture, 1991), Kahn was taking a page from his own education: "His emphasis on what he had come to call 'form,' the inherent essence that an architect had to discern in an architectural program before it was contaminated by practical considerations, was related to the Beaux-Arts emphasis on the preliminary, instinctive esquisse Glenn Murcutt's 1996-98 Fletcher-Page House has huge sliding glass doors that open to transform its living spaces into a porch. “I have a great desire to make a building which is just a big veranda,” Murcutt has said. Envisioning such a building as his house, he adds: “For myself, for my security at night, I would like to have

Glenn Murcutt's 1996-98 Fletcher-Page House has huge sliding glass doors that open to transform its living spaces into a porch. “I have a great desire to make a building which is just a big veranda,” Murcutt has said. Envisioning such a building as his house, he adds: “For myself, for my security at night, I would like to have  Koh Kitayama's 1994 F3 House uses a ready-made greenhouse to enclose a garage/party-space and a small elevated box that accommodates private living functions. The transparent greenhouse envelope might be seen as a variation on Glenn Murcutt's house-as-veranda, while its opaque interior box answers his wish for a secure one-room nocturnal retreat. The F3 House demonstrates what's possible when sensations replace established room types as generators of a house design.

Koh Kitayama's 1994 F3 House uses a ready-made greenhouse to enclose a garage/party-space and a small elevated box that accommodates private living functions. The transparent greenhouse envelope might be seen as a variation on Glenn Murcutt's house-as-veranda, while its opaque interior box answers his wish for a secure one-room nocturnal retreat. The F3 House demonstrates what's possible when sensations replace established room types as generators of a house design.

What Kitayama's F3 House sacrifices in conventional comfort and convenience, it makes up for in delight. The particular bargain it strikes may not suit everyone, but the bachelor who commissioned it probably wouldn't have a hard time finding a like-minded buyer if he chose to sell it. An interest and cars and parties might not even be required, given the broad appeal of a return to life under the sky's blue dome.

If design fantasy is to lead to anything more than jacuzzis and home theaters, it has to go beyond comfort. It must trade such "commodity" for the true delight of reconnection with life's fundamentals and the joy that automatically comes of being reminded we're alive. As blandest suburbia proves, unchecked convenience chokes out life. It reminds us of Thoreau, turning his back on the comfort of town "to front only the essential facts of life," and of the ardent hearted Huck Finn's farewell: "I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can't stand it. I been there before." Huck wasn't going to stand for a life choreographed by room names. He'd take the primal joy of his most basic condition, as a free body in space.

Rule 10 is to embrace inconvenience.

What Kitayama's F3 House sacrifices in conventional comfort and convenience, it makes up for in delight. The particular bargain it strikes may not suit everyone, but the bachelor who commissioned it probably wouldn't have a hard time finding a like-minded buyer if he chose to sell it. An interest and cars and parties might not even be required, given the broad appeal of a return to life under the sky's blue dome.

If design fantasy is to lead to anything more than jacuzzis and home theaters, it has to go beyond comfort. It must trade such "commodity" for the true delight of reconnection with life's fundamentals and the joy that automatically comes of being reminded we're alive. As blandest suburbia proves, unchecked convenience chokes out life. It reminds us of Thoreau, turning his back on the comfort of town "to front only the essential facts of life," and of the ardent hearted Huck Finn's farewell: "I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can't stand it. I been there before." Huck wasn't going to stand for a life choreographed by room names. He'd take the primal joy of his most basic condition, as a free body in space.

Rule 10 is to embrace inconvenience.

Pay attention to any place that ignites passion and take home its fire. A house that's based only on practical decisions and fears of missteps will never be more than sensible and timid. Too much comfort and convenience insulate people from life and its greatest and simplest pleasures. Design a house not just to support life, but to make living worthwhile.

Continue to House Rules Afterword

Pay attention to any place that ignites passion and take home its fire. A house that's based only on practical decisions and fears of missteps will never be more than sensible and timid. Too much comfort and convenience insulate people from life and its greatest and simplest pleasures. Design a house not just to support life, but to make living worthwhile.

Continue to House Rules AfterwordHouse Rule 9 - Build for Flexibility

While not the first great modern house, Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House is without doubt the most influential today. It embodies two especially pertinent ideas that support flexibility. Its standardized industrial components suggest a demountable and reusable kit-of-parts architecture which, sixty years since, is the concept behind today's explosive proliferation of prefabricated modular and recyclable housing solutions. The Farnsworth House is spatially adaptable as well. Its open plan reflects Mies's ideal of timeless "universal space," the usefulness of which might outlive ephemeral functional assignments. From the wheelchair of his later years, Mies would have appreciated a further merit of this open plan; its lack of physical barriers. Such a house has the potential to remain useful to an occupant whose own physical condition changes. Mies raised the Farnsworth House several feet off the ground to protect it from the flooding of an adjacent river, abandoning an on-grade alternative scheme might have made it truly accessible.

While not the first great modern house, Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House is without doubt the most influential today. It embodies two especially pertinent ideas that support flexibility. Its standardized industrial components suggest a demountable and reusable kit-of-parts architecture which, sixty years since, is the concept behind today's explosive proliferation of prefabricated modular and recyclable housing solutions. The Farnsworth House is spatially adaptable as well. Its open plan reflects Mies's ideal of timeless "universal space," the usefulness of which might outlive ephemeral functional assignments. From the wheelchair of his later years, Mies would have appreciated a further merit of this open plan; its lack of physical barriers. Such a house has the potential to remain useful to an occupant whose own physical condition changes. Mies raised the Farnsworth House several feet off the ground to protect it from the flooding of an adjacent river, abandoning an on-grade alternative scheme might have made it truly accessible.

Admittedly derived from the Farnsworth House, Philip Johnson's Glass House realizes the ground-resting condition of Mies's abandoned scheme. Now open to the public, the Glass House is readily made accessible to wheelchair users by way of the barely noticeable ramp shown in the photo above. Its open interior is likewise wheelchair-friendly.

Admittedly derived from the Farnsworth House, Philip Johnson's Glass House realizes the ground-resting condition of Mies's abandoned scheme. Now open to the public, the Glass House is readily made accessible to wheelchair users by way of the barely noticeable ramp shown in the photo above. Its open interior is likewise wheelchair-friendly.

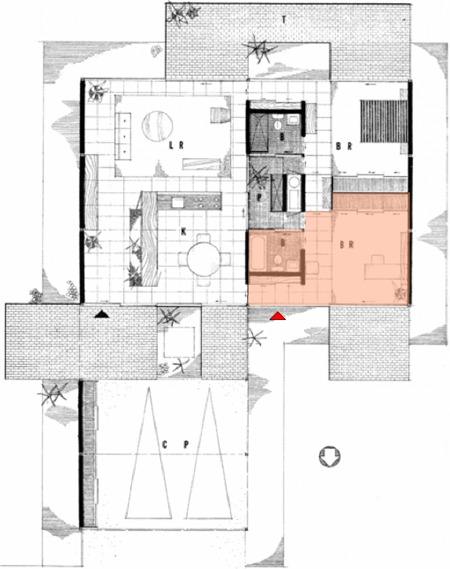

#21 in the canonical Case Study House series of model homes for post-war America, Pierre Koenig's 1958-60 Bailey House has a continuous circulation loop and system of pocket doors allow the entire house to be thrown open as a single bright space, giving the bedrooms a spatial vitality far surpassing their typical status as corridor-leg appendages. As noted in Rule 4's discussion of the house, this contributes to a one-room feel in the spirit of the Farnsworth House, but with greater practicality and privacy potential. Koenig's house has a pair of bed-and-bath suites, shown at right in the plan above. Although mirror images of each other and both labeled "BR," one is shown furnished as a study. Photos of the house taken over the years show that it has served both uses. The rooms contribute to the house's overall expansiveness even as their own openness and quality of space is elevated. Shaded in pink, the room shown as a study and its bathroom can be isolated from the rest of the house by pocket doors at either end of its grid-floored corridor segment. This area could be adapted to a private home office suitable for business visitors with the addition of an exterior door at the red arrow. While the house has only two bedrooms, it's sized to the typical American household of today, which consists of an individual or couple. Beyond the outsized spatial appeal Koenig leverages out of its modest size, the Bailey House's ready flexibility gives it an added dimension and a far greater resale appeal than the third or fourth bedrooms most Americans feel compelled to build with an eye toward the next buyer, and then pay to heat, cool and amortize while they stand empty for years. The Bailey House's single level, openness and looping circulation path all make it adaptable in a way few American houses are; it could be a supportive home to a wheelchair user.

#21 in the canonical Case Study House series of model homes for post-war America, Pierre Koenig's 1958-60 Bailey House has a continuous circulation loop and system of pocket doors allow the entire house to be thrown open as a single bright space, giving the bedrooms a spatial vitality far surpassing their typical status as corridor-leg appendages. As noted in Rule 4's discussion of the house, this contributes to a one-room feel in the spirit of the Farnsworth House, but with greater practicality and privacy potential. Koenig's house has a pair of bed-and-bath suites, shown at right in the plan above. Although mirror images of each other and both labeled "BR," one is shown furnished as a study. Photos of the house taken over the years show that it has served both uses. The rooms contribute to the house's overall expansiveness even as their own openness and quality of space is elevated. Shaded in pink, the room shown as a study and its bathroom can be isolated from the rest of the house by pocket doors at either end of its grid-floored corridor segment. This area could be adapted to a private home office suitable for business visitors with the addition of an exterior door at the red arrow. While the house has only two bedrooms, it's sized to the typical American household of today, which consists of an individual or couple. Beyond the outsized spatial appeal Koenig leverages out of its modest size, the Bailey House's ready flexibility gives it an added dimension and a far greater resale appeal than the third or fourth bedrooms most Americans feel compelled to build with an eye toward the next buyer, and then pay to heat, cool and amortize while they stand empty for years. The Bailey House's single level, openness and looping circulation path all make it adaptable in a way few American houses are; it could be a supportive home to a wheelchair user.

Renzo Piano's expansion of the Morgan Library was completed in 2006. Wheelchair users enter it without the stigma of segregation onto a diverging ramp, alongside companions on foot by means of the same sloped surface and separated only by an assisting rail. In the manner of their day, the architects of the original Morgan buildings physically and metaphorically elevated their main floors and created a sense of transition from the everyday sidewalk with gracious but discriminatory stairs. While it's still common for new entrance designs to provide a central stair and side-ramp, Piano's resourcefulness serves the dignity of his building and all its users at once, with arresting simplicity. The new Morgan entrance approaches the aim of Universal Design, "the design of products and environments to be usable by all people." An emerging and more integrated approach to "handicapped accessibility," Universal Design is especially pertinent to housing; it would not only allow American baby-boomers to age in place, but would make for a home that those with disabilities can visit or consider buying. Retrofitting a house to be accessible is expensive, but building a new house that's accessible costs very little more than building one that's not. The open spatial quality that makes a house accessible has entirely separate merits, compatible with several of the other House Rules.

Renzo Piano's expansion of the Morgan Library was completed in 2006. Wheelchair users enter it without the stigma of segregation onto a diverging ramp, alongside companions on foot by means of the same sloped surface and separated only by an assisting rail. In the manner of their day, the architects of the original Morgan buildings physically and metaphorically elevated their main floors and created a sense of transition from the everyday sidewalk with gracious but discriminatory stairs. While it's still common for new entrance designs to provide a central stair and side-ramp, Piano's resourcefulness serves the dignity of his building and all its users at once, with arresting simplicity. The new Morgan entrance approaches the aim of Universal Design, "the design of products and environments to be usable by all people." An emerging and more integrated approach to "handicapped accessibility," Universal Design is especially pertinent to housing; it would not only allow American baby-boomers to age in place, but would make for a home that those with disabilities can visit or consider buying. Retrofitting a house to be accessible is expensive, but building a new house that's accessible costs very little more than building one that's not. The open spatial quality that makes a house accessible has entirely separate merits, compatible with several of the other House Rules.

Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House was built in 1974-75 and later bought and enlarged by the architect, in 1981-82. Murcutt often cites the Aboriginal proverb, "Touch this earth lightly," words taken by architectural historian Philip Drew as the title of his 1999 book on the architect. In it, Murcutt says of his design for the Marie Short House, "It was very important that the house could be modified and undergo major surgery and still retain its integrity. I came along, some years later . . . and altered it. . . . What was so exciting to me was that I was able to re-use the original veranda, the galvanized iron roof, every piece of it, including the louvre frame, gable end - the entire end came out and was unbolted. . . . If I wanted to, I could unbolt half the house and trundle it off into the forest and modify it minimally and have a complete house. I can put them together, pull them apart, change them, and they will retain an integrity, wherever I place them." They'll also retain vitality, thanks to their ability to respond to new demands. By contrast, the house that's built for the ages is a monument to a moment, but necessarily loses vitality with time. Detroit and other rust-belt cities are reminders that not just houses but entire neighborhoods outlive their usefulness. A house that's designed for recycling, if not re-use, acknowledges the transience of human life. A house that's designed for permanence flatters the owner's ego to his face while mocking his mortality behind his back. Murcutt is deeply influenced by Thoreau, who built his cabin at Walden Pond with "Refuse shingles . . . second-hand windows" and "one thousand old brick," demonstrating the affordability of a house built "for a lifetime," and by implication, no more. As he wrote in Walden: "Most of the stone a nation hammers goes toward its tomb only." Murcutt seems to elaborate in Touch This Earth Lightly: "We are part of this whole - we are not the whole. Our being here is really the most transitory aspect of the planet. It is trees, it is climate, it is the earth, the water, the rocks and the landscape which is real. When we fail to see ourselves belonging to and as a part of that we become unreal."

Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House was built in 1974-75 and later bought and enlarged by the architect, in 1981-82. Murcutt often cites the Aboriginal proverb, "Touch this earth lightly," words taken by architectural historian Philip Drew as the title of his 1999 book on the architect. In it, Murcutt says of his design for the Marie Short House, "It was very important that the house could be modified and undergo major surgery and still retain its integrity. I came along, some years later . . . and altered it. . . . What was so exciting to me was that I was able to re-use the original veranda, the galvanized iron roof, every piece of it, including the louvre frame, gable end - the entire end came out and was unbolted. . . . If I wanted to, I could unbolt half the house and trundle it off into the forest and modify it minimally and have a complete house. I can put them together, pull them apart, change them, and they will retain an integrity, wherever I place them." They'll also retain vitality, thanks to their ability to respond to new demands. By contrast, the house that's built for the ages is a monument to a moment, but necessarily loses vitality with time. Detroit and other rust-belt cities are reminders that not just houses but entire neighborhoods outlive their usefulness. A house that's designed for recycling, if not re-use, acknowledges the transience of human life. A house that's designed for permanence flatters the owner's ego to his face while mocking his mortality behind his back. Murcutt is deeply influenced by Thoreau, who built his cabin at Walden Pond with "Refuse shingles . . . second-hand windows" and "one thousand old brick," demonstrating the affordability of a house built "for a lifetime," and by implication, no more. As he wrote in Walden: "Most of the stone a nation hammers goes toward its tomb only." Murcutt seems to elaborate in Touch This Earth Lightly: "We are part of this whole - we are not the whole. Our being here is really the most transitory aspect of the planet. It is trees, it is climate, it is the earth, the water, the rocks and the landscape which is real. When we fail to see ourselves belonging to and as a part of that we become unreal."

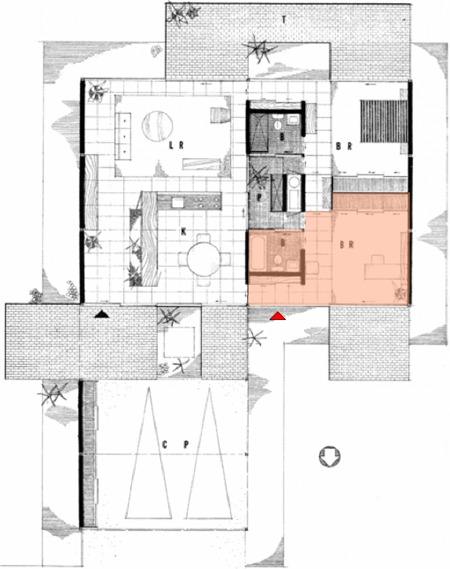

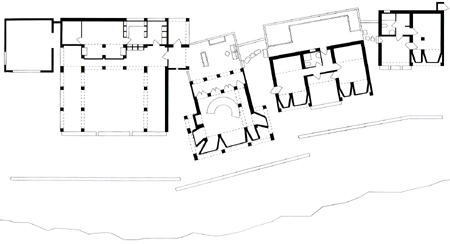

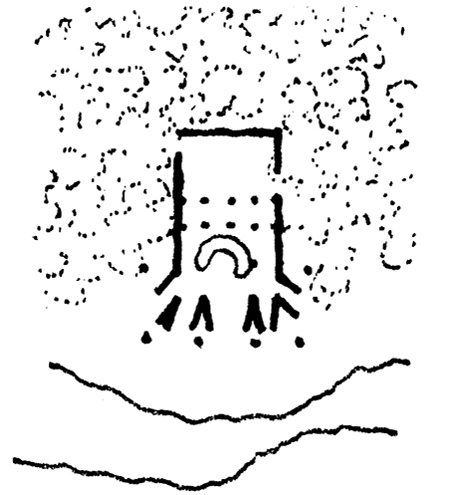

The plan of Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House in its original form, top, and as enlarged, bottom. The design lent itself to expansion in the re-usability of its components and in its extrudable form and longitudinal circulation axes. Mies's linear, modular Farnsworth House is an influence Murcutt has acknowledged.

The plan of Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House in its original form, top, and as enlarged, bottom. The design lent itself to expansion in the re-usability of its components and in its extrudable form and longitudinal circulation axes. Mies's linear, modular Farnsworth House is an influence Murcutt has acknowledged.

Werner Sobek's glass houses, R128 was completed in 2000, in Stuttgart, Germany. Sobek holds the Mies van der Rohe visiting professorship at Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies was for many years head of the architecture school. Sobek's houses can be seen as an effort to render Mies's vision environmentally responsible. R128 is entirely energy self-sufficient. It uses triple glazing, geothermal heating and cooling, and horizontal rooftop solar panels to dispense with fossil fuels and emissions altogether. Flexibility is a further sustainable aspect of its design. Sobek's conviction that "it is unethical to throw things away" is reflected in his buildings' construction from modular elements that can be detached and re-used elsewhere, realizing the recyclability that the Farnsworth house only suggested. Its three-dimensional steel grid has easily removed floor, wall and roof panels that might be reconfigured into a new house.

Rule 9 is to build for flexibility.

Werner Sobek's glass houses, R128 was completed in 2000, in Stuttgart, Germany. Sobek holds the Mies van der Rohe visiting professorship at Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies was for many years head of the architecture school. Sobek's houses can be seen as an effort to render Mies's vision environmentally responsible. R128 is entirely energy self-sufficient. It uses triple glazing, geothermal heating and cooling, and horizontal rooftop solar panels to dispense with fossil fuels and emissions altogether. Flexibility is a further sustainable aspect of its design. Sobek's conviction that "it is unethical to throw things away" is reflected in his buildings' construction from modular elements that can be detached and re-used elsewhere, realizing the recyclability that the Farnsworth house only suggested. Its three-dimensional steel grid has easily removed floor, wall and roof panels that might be reconfigured into a new house.

Rule 9 is to build for flexibility.

Design for change. Provide areas of different spatial qualities and levels of intimacy or privacy that might serve a variety of purposes, not rooms dedicated to single or fixed roles. Save space by designing areas to serve more than one function. Place critical spaces on the first floor or make the entire house one-story for ease of access to people of different degrees of mobility, and to allow residents to age in place. If more space might eventually be needed, place the house on its site to leave room for an addition, give it a shape that's easily extended, and design circulation and services to support growth. Anticipate the end of the house's usefulness, and design for easy disassembly and recycling.

Continue to House Rule 10

Design for change. Provide areas of different spatial qualities and levels of intimacy or privacy that might serve a variety of purposes, not rooms dedicated to single or fixed roles. Save space by designing areas to serve more than one function. Place critical spaces on the first floor or make the entire house one-story for ease of access to people of different degrees of mobility, and to allow residents to age in place. If more space might eventually be needed, place the house on its site to leave room for an addition, give it a shape that's easily extended, and design circulation and services to support growth. Anticipate the end of the house's usefulness, and design for easy disassembly and recycling.

Continue to House Rule 10

House Rule 9 - Build for Flexibility

While not the first great modern house, Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House is without doubt the most influential today. It embodies two especially pertinent ideas that support flexibility. Its standardized industrial components suggest a demountable and reusable kit-of-parts architecture which, sixty years since, is the concept behind today's explosive proliferation of prefabricated modular and recyclable housing solutions. The Farnsworth House is spatially adaptable as well. Its open plan reflects Mies's ideal of timeless "universal space," the usefulness of which might outlive ephemeral functional assignments. From the wheelchair of his later years, Mies would have appreciated a further merit of this open plan; its lack of physical barriers. Such a house has the potential to remain useful to an occupant whose own physical condition changes. Mies raised the Farnsworth House several feet off the ground to protect it from the flooding of an adjacent river, abandoning an on-grade alternative scheme might have made it truly accessible.

While not the first great modern house, Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House is without doubt the most influential today. It embodies two especially pertinent ideas that support flexibility. Its standardized industrial components suggest a demountable and reusable kit-of-parts architecture which, sixty years since, is the concept behind today's explosive proliferation of prefabricated modular and recyclable housing solutions. The Farnsworth House is spatially adaptable as well. Its open plan reflects Mies's ideal of timeless "universal space," the usefulness of which might outlive ephemeral functional assignments. From the wheelchair of his later years, Mies would have appreciated a further merit of this open plan; its lack of physical barriers. Such a house has the potential to remain useful to an occupant whose own physical condition changes. Mies raised the Farnsworth House several feet off the ground to protect it from the flooding of an adjacent river, abandoning an on-grade alternative scheme might have made it truly accessible.

Admittedly derived from the Farnsworth House, Philip Johnson's Glass House realizes the ground-resting condition of Mies's abandoned scheme. Now open to the public, the Glass House is readily made accessible to wheelchair users by way of the barely noticeable ramp shown in the photo above. Its open interior is likewise wheelchair-friendly.

Admittedly derived from the Farnsworth House, Philip Johnson's Glass House realizes the ground-resting condition of Mies's abandoned scheme. Now open to the public, the Glass House is readily made accessible to wheelchair users by way of the barely noticeable ramp shown in the photo above. Its open interior is likewise wheelchair-friendly.

#21 in the canonical Case Study House series of model homes for post-war America, Pierre Koenig's 1958-60 Bailey House has a continuous circulation loop and system of pocket doors allow the entire house to be thrown open as a single bright space, giving the bedrooms a spatial vitality far surpassing their typical status as corridor-leg appendages. As noted in Rule 4's discussion of the house, this contributes to a one-room feel in the spirit of the Farnsworth House, but with greater practicality and privacy potential. Koenig's house has a pair of bed-and-bath suites, shown at right in the plan above. Although mirror images of each other and both labeled "BR," one is shown furnished as a study. Photos of the house taken over the years show that it has served both uses. The rooms contribute to the house's overall expansiveness even as their own openness and quality of space is elevated. Shaded in pink, the room shown as a study and its bathroom can be isolated from the rest of the house by pocket doors at either end of its grid-floored corridor segment. This area could be adapted to a private home office suitable for business visitors with the addition of an exterior door at the red arrow. While the house has only two bedrooms, it's sized to the typical American household of today, which consists of an individual or couple. Beyond the outsized spatial appeal Koenig leverages out of its modest size, the Bailey House's ready flexibility gives it an added dimension and a far greater resale appeal than the third or fourth bedrooms most Americans feel compelled to build with an eye toward the next buyer, and then pay to heat, cool and amortize while they stand empty for years. The Bailey House's single level, openness and looping circulation path all make it adaptable in a way few American houses are; it could be a supportive home to a wheelchair user.

#21 in the canonical Case Study House series of model homes for post-war America, Pierre Koenig's 1958-60 Bailey House has a continuous circulation loop and system of pocket doors allow the entire house to be thrown open as a single bright space, giving the bedrooms a spatial vitality far surpassing their typical status as corridor-leg appendages. As noted in Rule 4's discussion of the house, this contributes to a one-room feel in the spirit of the Farnsworth House, but with greater practicality and privacy potential. Koenig's house has a pair of bed-and-bath suites, shown at right in the plan above. Although mirror images of each other and both labeled "BR," one is shown furnished as a study. Photos of the house taken over the years show that it has served both uses. The rooms contribute to the house's overall expansiveness even as their own openness and quality of space is elevated. Shaded in pink, the room shown as a study and its bathroom can be isolated from the rest of the house by pocket doors at either end of its grid-floored corridor segment. This area could be adapted to a private home office suitable for business visitors with the addition of an exterior door at the red arrow. While the house has only two bedrooms, it's sized to the typical American household of today, which consists of an individual or couple. Beyond the outsized spatial appeal Koenig leverages out of its modest size, the Bailey House's ready flexibility gives it an added dimension and a far greater resale appeal than the third or fourth bedrooms most Americans feel compelled to build with an eye toward the next buyer, and then pay to heat, cool and amortize while they stand empty for years. The Bailey House's single level, openness and looping circulation path all make it adaptable in a way few American houses are; it could be a supportive home to a wheelchair user.

Renzo Piano's expansion of the Morgan Library was completed in 2006. Wheelchair users enter it without the stigma of segregation onto a diverging ramp, alongside companions on foot by means of the same sloped surface and separated only by an assisting rail. In the manner of their day, the architects of the original Morgan buildings physically and metaphorically elevated their main floors and created a sense of transition from the everyday sidewalk with gracious but discriminatory stairs. While it's still common for new entrance designs to provide a central stair and side-ramp, Piano's resourcefulness serves the dignity of his building and all its users at once, with arresting simplicity. The new Morgan entrance approaches the aim of Universal Design, "the design of products and environments to be usable by all people." An emerging and more integrated approach to "handicapped accessibility," Universal Design is especially pertinent to housing; it would not only allow American baby-boomers to age in place, but would make for a home that those with disabilities can visit or consider buying. Retrofitting a house to be accessible is expensive, but building a new house that's accessible costs very little more than building one that's not. The open spatial quality that makes a house accessible has entirely separate merits, compatible with several of the other House Rules.

Renzo Piano's expansion of the Morgan Library was completed in 2006. Wheelchair users enter it without the stigma of segregation onto a diverging ramp, alongside companions on foot by means of the same sloped surface and separated only by an assisting rail. In the manner of their day, the architects of the original Morgan buildings physically and metaphorically elevated their main floors and created a sense of transition from the everyday sidewalk with gracious but discriminatory stairs. While it's still common for new entrance designs to provide a central stair and side-ramp, Piano's resourcefulness serves the dignity of his building and all its users at once, with arresting simplicity. The new Morgan entrance approaches the aim of Universal Design, "the design of products and environments to be usable by all people." An emerging and more integrated approach to "handicapped accessibility," Universal Design is especially pertinent to housing; it would not only allow American baby-boomers to age in place, but would make for a home that those with disabilities can visit or consider buying. Retrofitting a house to be accessible is expensive, but building a new house that's accessible costs very little more than building one that's not. The open spatial quality that makes a house accessible has entirely separate merits, compatible with several of the other House Rules.

Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House was built in 1974-75 and later bought and enlarged by the architect, in 1981-82. Murcutt often cites the Aboriginal proverb, "Touch this earth lightly," words taken by architectural historian Philip Drew as the title of his 1999 book on the architect. In it, Murcutt says of his design for the Marie Short House, "It was very important that the house could be modified and undergo major surgery and still retain its integrity. I came along, some years later . . . and altered it. . . . What was so exciting to me was that I was able to re-use the original veranda, the galvanized iron roof, every piece of it, including the louvre frame, gable end - the entire end came out and was unbolted. . . . If I wanted to, I could unbolt half the house and trundle it off into the forest and modify it minimally and have a complete house. I can put them together, pull them apart, change them, and they will retain an integrity, wherever I place them." They'll also retain vitality, thanks to their ability to respond to new demands. By contrast, the house that's built for the ages is a monument to a moment, but necessarily loses vitality with time. Detroit and other rust-belt cities are reminders that not just houses but entire neighborhoods outlive their usefulness. A house that's designed for recycling, if not re-use, acknowledges the transience of human life. A house that's designed for permanence flatters the owner's ego to his face while mocking his mortality behind his back. Murcutt is deeply influenced by Thoreau, who built his cabin at Walden Pond with "Refuse shingles . . . second-hand windows" and "one thousand old brick," demonstrating the affordability of a house built "for a lifetime," and by implication, no more. As he wrote in Walden: "Most of the stone a nation hammers goes toward its tomb only." Murcutt seems to elaborate in Touch This Earth Lightly: "We are part of this whole - we are not the whole. Our being here is really the most transitory aspect of the planet. It is trees, it is climate, it is the earth, the water, the rocks and the landscape which is real. When we fail to see ourselves belonging to and as a part of that we become unreal."

Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House was built in 1974-75 and later bought and enlarged by the architect, in 1981-82. Murcutt often cites the Aboriginal proverb, "Touch this earth lightly," words taken by architectural historian Philip Drew as the title of his 1999 book on the architect. In it, Murcutt says of his design for the Marie Short House, "It was very important that the house could be modified and undergo major surgery and still retain its integrity. I came along, some years later . . . and altered it. . . . What was so exciting to me was that I was able to re-use the original veranda, the galvanized iron roof, every piece of it, including the louvre frame, gable end - the entire end came out and was unbolted. . . . If I wanted to, I could unbolt half the house and trundle it off into the forest and modify it minimally and have a complete house. I can put them together, pull them apart, change them, and they will retain an integrity, wherever I place them." They'll also retain vitality, thanks to their ability to respond to new demands. By contrast, the house that's built for the ages is a monument to a moment, but necessarily loses vitality with time. Detroit and other rust-belt cities are reminders that not just houses but entire neighborhoods outlive their usefulness. A house that's designed for recycling, if not re-use, acknowledges the transience of human life. A house that's designed for permanence flatters the owner's ego to his face while mocking his mortality behind his back. Murcutt is deeply influenced by Thoreau, who built his cabin at Walden Pond with "Refuse shingles . . . second-hand windows" and "one thousand old brick," demonstrating the affordability of a house built "for a lifetime," and by implication, no more. As he wrote in Walden: "Most of the stone a nation hammers goes toward its tomb only." Murcutt seems to elaborate in Touch This Earth Lightly: "We are part of this whole - we are not the whole. Our being here is really the most transitory aspect of the planet. It is trees, it is climate, it is the earth, the water, the rocks and the landscape which is real. When we fail to see ourselves belonging to and as a part of that we become unreal."

The plan of Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House in its original form, top, and as enlarged, bottom. The design lent itself to expansion in the re-usability of its components and in its extrudable form and longitudinal circulation axes. Mies's linear, modular Farnsworth House is an influence Murcutt has acknowledged.

The plan of Glenn Murcutt's Marie Short House in its original form, top, and as enlarged, bottom. The design lent itself to expansion in the re-usability of its components and in its extrudable form and longitudinal circulation axes. Mies's linear, modular Farnsworth House is an influence Murcutt has acknowledged.

Werner Sobek's glass houses, R128 was completed in 2000, in Stuttgart, Germany. Sobek holds the Mies van der Rohe visiting professorship at Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies was for many years head of the architecture school. Sobek's houses can be seen as an effort to render Mies's vision environmentally responsible. R128 is entirely energy self-sufficient. It uses triple glazing, geothermal heating and cooling, and horizontal rooftop solar panels to dispense with fossil fuels and emissions altogether. Flexibility is a further sustainable aspect of its design. Sobek's conviction that "it is unethical to throw things away" is reflected in his buildings' construction from modular elements that can be detached and re-used elsewhere, realizing the recyclability that the Farnsworth house only suggested. Its three-dimensional steel grid has easily removed floor, wall and roof panels that might be reconfigured into a new house.

Rule 9 is to build for flexibility.

Werner Sobek's glass houses, R128 was completed in 2000, in Stuttgart, Germany. Sobek holds the Mies van der Rohe visiting professorship at Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies was for many years head of the architecture school. Sobek's houses can be seen as an effort to render Mies's vision environmentally responsible. R128 is entirely energy self-sufficient. It uses triple glazing, geothermal heating and cooling, and horizontal rooftop solar panels to dispense with fossil fuels and emissions altogether. Flexibility is a further sustainable aspect of its design. Sobek's conviction that "it is unethical to throw things away" is reflected in his buildings' construction from modular elements that can be detached and re-used elsewhere, realizing the recyclability that the Farnsworth house only suggested. Its three-dimensional steel grid has easily removed floor, wall and roof panels that might be reconfigured into a new house.

Rule 9 is to build for flexibility.

Design for change. Provide areas of different spatial qualities and levels of intimacy or privacy that might serve a variety of purposes, not rooms dedicated to single or fixed roles. Save space by designing areas to serve more than one function. Place critical spaces on the first floor or make the entire house one-story for ease of access to people of different degrees of mobility, and to allow residents to age in place. If more space might eventually be needed, place the house on its site to leave room for an addition, give it a shape that's easily extended, and design circulation and services to support growth. Anticipate the end of the house's usefulness, and design for easy disassembly and recycling.

Continue to House Rule 10

Design for change. Provide areas of different spatial qualities and levels of intimacy or privacy that might serve a variety of purposes, not rooms dedicated to single or fixed roles. Save space by designing areas to serve more than one function. Place critical spaces on the first floor or make the entire house one-story for ease of access to people of different degrees of mobility, and to allow residents to age in place. If more space might eventually be needed, place the house on its site to leave room for an addition, give it a shape that's easily extended, and design circulation and services to support growth. Anticipate the end of the house's usefulness, and design for easy disassembly and recycling.

Continue to House Rule 10

House Rule 8 - Use Trees

"Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?" Theodore Roethke asked in his 1953 poem, "The Waking." Trees have been our natural environment since before we came down from them, and they hold a deeply embedded place in the human psyche. Their generations of leaves are an intuitive metaphor for death and renewal. In a poem that contemplates mortality, did Roethke want his listeners to unconsciously hear "blight takes the tree?" Or just recall the redemptive wonder we feel on seeing a tree mysteriously transformed by sunlight? Beyond a metaphysical import, every tree has specific qualities that might influence its selection as an intermediary between artificial shelter and nature. The poplar pictured above, for example, has brittle leaves that make the wind audible as a gentle clapping.

"Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?" Theodore Roethke asked in his 1953 poem, "The Waking." Trees have been our natural environment since before we came down from them, and they hold a deeply embedded place in the human psyche. Their generations of leaves are an intuitive metaphor for death and renewal. In a poem that contemplates mortality, did Roethke want his listeners to unconsciously hear "blight takes the tree?" Or just recall the redemptive wonder we feel on seeing a tree mysteriously transformed by sunlight? Beyond a metaphysical import, every tree has specific qualities that might influence its selection as an intermediary between artificial shelter and nature. The poplar pictured above, for example, has brittle leaves that make the wind audible as a gentle clapping.

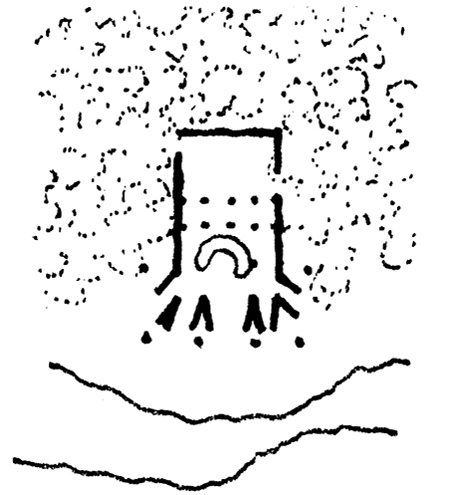

Philip Johnson called his Glass House a "pavilion for viewing nature," and referred to its lush setting as "expensive wallpaper." A year after the house's completion, Johnson explained its formal influences in the September, 1950, issue of Architectural Review. The uncaptioned photo above accompanied his article, a goes-without-saying nod to his design's source in the landscape. The image also highlights the incidental but pervasive and integral effect of trees as animating sources of shadow and reflection.

Philip Johnson called his Glass House a "pavilion for viewing nature," and referred to its lush setting as "expensive wallpaper." A year after the house's completion, Johnson explained its formal influences in the September, 1950, issue of Architectural Review. The uncaptioned photo above accompanied his article, a goes-without-saying nod to his design's source in the landscape. The image also highlights the incidental but pervasive and integral effect of trees as animating sources of shadow and reflection.

Caspar David Friedrich's 1822 painting, "Noon," captures the fundamental allure of a stand of trees. In his 1963 book, Ecology, Eugene Odum wrote: "Human civilization has so far reached its greatest development in what was originally forest and grassland in temperate regions. . . . Man, in fact, tends to combine features of both grasslands and forests into a habitat for himself that might be called forest edge. . . . in grassland regions he plants trees around his homes, towns, and farms. . . . when man settles in the forest he replaces most of it with grasslands and croplands, but leaves patches of the original forest on farms and around residential areas. . . . man depends on grasslands for food, but likes to live and play in the shelter of the forest."

Caspar David Friedrich's 1822 painting, "Noon," captures the fundamental allure of a stand of trees. In his 1963 book, Ecology, Eugene Odum wrote: "Human civilization has so far reached its greatest development in what was originally forest and grassland in temperate regions. . . . Man, in fact, tends to combine features of both grasslands and forests into a habitat for himself that might be called forest edge. . . . in grassland regions he plants trees around his homes, towns, and farms. . . . when man settles in the forest he replaces most of it with grasslands and croplands, but leaves patches of the original forest on farms and around residential areas. . . . man depends on grasslands for food, but likes to live and play in the shelter of the forest."

An admirer of Caspar David Friedrich, the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel painted "Landscape with Gothic Arcades" in 1811. The romantic appeal of Schinkel's architectural vision is closely related to the natural pull of Friedrich's grove in "Noon." The architect Robert Geddes' 1982 essay in Architectural Design, "The Forest Edge," quotes the passage above from Eugene Odum's Ecology, and takes its title from his name for man's prefered environment. The forest edge, Geddes wrote, "can be seen both as man's ideal habitat and as a mythical image. Consequently, just as man has enjoyed the forest at the edge of the clearing which has offered him both shelter and openness, so today we enjoy being in architecture which recreates similar spatial conditions: arcades and colonnades, loggias and porches, thresholds, cloisters, courtyards and peristyles - all of which resemble clearings at the edge of the forest."