News

Saving the Seamen's House YMCA

Designed as a waterfront YMCA for sailors, Seamen's House has scores of multi-colored terra cotta highlights. Stylized ships' prows, waves, and Jazz Age riffs on the YMCA's triangle logo are deployed for maximum effect, lighting up the building's roof line and window heads. They are an integral part of the building's composition, and their cleaning and minimal restoration would do much to revitalize a work by great Art Deco designers. Heavy-framed, rusty security screens tell of the building's more recent use as a prison. Their removal would also greatly improve the appeal of this easily overlooked building.

Built in 1930-1932, the Seamen’s House YMCA was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon at the very time the architects were at work on the Empire State Building. This photo, published in Architectural Record in May, 1932, shows a large sign advertising the institution's presence to sailors up and down pier-lined Eleventh Avenue.

Despite security accretions, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon's elegant entrance still gives the block a graceful corner . . .

. . . including a sleek ship silhouette . . .

. . . and sculpted-in lighting fixtures just begging for restoration.

. . . and sculpted-in lighting fixtures just begging for restoration.

The building's soot smudged brick and terra cotta would revive dramatically with cleaning and less sloppy repointing . . .

. . . just as removal of the prison's roof fence would restore a romantic skyline.

An 1930s Bromley Atlas shows the Seamen's House YMCA, top center, directly across from the White Star Line piers for which the Titanic had set out.

Sprawling from Little West 12th to West 23rd Street, the Chelsea Piers were designed by Warren & Wetmore, architects of Grand Central Terminal. The future site of the Seamen's House YMCA is in the left distance in this photo.

The piers' grand, globe-peaked street front is sadly gone, a caution to those who would throw away the kind of architecture no longer made. (Warren & Wetmore's Michigan Central Station may stand as a symbol of Detroit's decline, but it stands nonetheless, holding a possibility of rebirth.)

The Seamen's House YMCA operated until 1966, after which its building was made a medium security women's prison, the Bayview Correctional Facility. As reported in a New York Times article on Tuesday, that role has ended and the state plans to sell the building. The article quotes local community board member Pamela Wolff as saying she considers the prison's loss a tragedy: “The amount of recidivism was minimal. For those women, for this community, which for 35 years has been in perfect harmony with the use of that facility, the repercussions will never be measured.” Unlike upstate facilities, Bayview's location allowed women to be near their families, a critical factor for those - many of them non-violent Rockefeller drug law violators - primarily needing to just get their lives back on track. Ms. Wolff's sentiment reflects a larger concern, the loss of inclusive community fabric to steamrolling fabulousness. What Chelsea faces today is a different animal from gentrification. Beyond natives displaced by the rich, basic social building blocks from the corner store to rehabilitation facilities are giving way to tourist attractions and extra homes for the super-rich.

Developers are said to be circling the Seamen's House YMCA like vultures, but others have expressed less mercenary interest. Anne Elliott of Greenhope Services for Women would like to see the building help formerly imprisoned women transition back to community life. Greenhope has a renovation architect on board and much good will in Chelsea. With an eye on the building's still existing YMCA gym and pool, Hudson Guild Director Ken Jockers sees a venue for dedicated, programmable community space. These purposes would make use of the building's existing interior while preserving an exterior that irreplaceably embodies the community's unique past and the authenticity of its historic identity.

The building's fate turns on the receptiveness of the Governor's office and creation of preservation and re-use strategies that can harness market forces. The building is not a landmark, and its sale into private hands puts it at great risk of demolition for new development. Community Board 4 has asked the Landmarks Preservation Commission to evaluate Seamen's House for landmark designation. This would be warranted not just by the building's substantial architectural merit, but perhaps even more by the unique working-waterfront history it tells. At the time Seamen's House was built, the YMCA was one of three seamen's welfare organizations operating on the Greenwich Village-Chelsea waterfront, along with the American Seamen’s Friend Society and the Seamen’s Christian Association.

Designating Seamen's House a landmark would be consistent with the designation in 2000 of the American Seamen’s Friend Society Sailors’ Home and Institute at 505-507 West Street, now the Jane Hotel, as well as the 2007 designation of the Keller Hotel at 150 Barrow Street. The latter is cited in its landmark designation report as “a significant reminder of the era when the Port of New York was one of the world’s busiest and the section of the Hudson River between Christopher and 23rd Streets was the heart of the busiest section of the Port of New York,” a description which applies no less to Seamen’s House.

What might replace the Seamen's House YMCA? Predictably, out-of-sight luxury condominiums for mainly absent and never seen residents, like 200 Eleventh Avenue. Its forbidding, anonymous and lifeless street presence says everything about these buildings' contribution to the community. The dead zone around it isn't even animated by residents walking through its lobby doors. When in town, they're driven onto a car elevator and ascend to "sky garages" adjoining their apartments, averting any risk of exposure to the community.

It's a tribute to Chelsea that its citizens can lament the closing of a local prison that kept inmates close to their outside support network. In the city at large, community introduction of social programs from halfway houses to public high schools routinely meets with agreement that they are necessary, just "not in my back yard," the source of the acronym, NIMBY. Pro-development types have co-opted this term, painting preservationists as NIMBYs against new construction. Their appropriation of it conveniently diverts accusations of self interest from themselves onto community advocates. They should know the label won't stick to Chelsea.

Saving the Seamen's House YMCA

Designed as a waterfront YMCA for sailors, Seamen's House has scores of multi-colored terra cotta highlights. Stylized ships' prows, waves, and Jazz Age riffs on the YMCA's triangle logo are deployed for maximum effect, lighting up the building's roof line and window heads. They are an integral part of the building's composition, and their cleaning and minimal restoration would do much to revitalize a work by great Art Deco designers. Heavy-framed, rusty security screens tell of the building's more recent use as a prison. Their removal would also greatly improve the appeal of this easily overlooked building.

Built in 1930-1932, the Seamen’s House YMCA was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon at the very time the architects were at work on the Empire State Building. This photo, published in Architectural Record in May, 1932, shows a large sign advertising the institution's presence to sailors up and down pier-lined Eleventh Avenue.

Despite security accretions, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon's elegant entrance still gives the block a graceful corner . . .

. . . including a sleek ship silhouette . . .

. . . and sculpted-in lighting fixtures just begging for restoration.

. . . and sculpted-in lighting fixtures just begging for restoration.

The building's soot smudged brick and terra cotta would revive dramatically with cleaning and less sloppy repointing . . .

. . . just as removal of the prison's roof fence would restore a romantic skyline.

An 1930s Bromley Atlas shows the Seamen's House YMCA, top center, directly across from the White Star Line piers for which the Titanic had set out.

Sprawling from Little West 12th to West 23rd Street, the Chelsea Piers were designed by Warren & Wetmore, architects of Grand Central Terminal. The future site of the Seamen's House YMCA is in the left distance in this photo.

The piers' grand, globe-peaked street front is sadly gone, a caution to those who would throw away the kind of architecture no longer made. (Warren & Wetmore's Michigan Central Station may stand as a symbol of Detroit's decline, but it stands nonetheless, holding a possibility of rebirth.)

The Seamen's House YMCA operated until 1966, after which its building was made a medium security women's prison, the Bayview Correctional Facility. As reported in a New York Times article on Tuesday, that role has ended and the state plans to sell the building. The article quotes local community board member Pamela Wolff as saying she considers the prison's loss a tragedy: “The amount of recidivism was minimal. For those women, for this community, which for 35 years has been in perfect harmony with the use of that facility, the repercussions will never be measured.” Unlike upstate facilities, Bayview's location allowed women to be near their families, a critical factor for those - many of them non-violent Rockefeller drug law violators - primarily needing to just get their lives back on track. Ms. Wolff's sentiment reflects a larger concern, the loss of inclusive community fabric to steamrolling fabulousness. What Chelsea faces today is a different animal from gentrification. Beyond natives displaced by the rich, basic social building blocks from the corner store to rehabilitation facilities are giving way to tourist attractions and extra homes for the super-rich.

Developers are said to be circling the Seamen's House YMCA like vultures, but others have expressed less mercenary interest. Anne Elliott of Greenhope Services for Women would like to see the building help formerly imprisoned women transition back to community life. Greenhope has a renovation architect on board and much good will in Chelsea. With an eye on the building's still existing YMCA gym and pool, Hudson Guild Director Ken Jockers sees a venue for dedicated, programmable community space. These purposes would make use of the building's existing interior while preserving an exterior that irreplaceably embodies the community's unique past and the authenticity of its historic identity.

The building's fate turns on the receptiveness of the Governor's office and creation of preservation and re-use strategies that can harness market forces. The building is not a landmark, and its sale into private hands puts it at great risk of demolition for new development. Community Board 4 has asked the Landmarks Preservation Commission to evaluate Seamen's House for landmark designation. This would be warranted not just by the building's substantial architectural merit, but perhaps even more by the unique working-waterfront history it tells. At the time Seamen's House was built, the YMCA was one of three seamen's welfare organizations operating on the Greenwich Village-Chelsea waterfront, along with the American Seamen’s Friend Society and the Seamen’s Christian Association.

Designating Seamen's House a landmark would be consistent with the designation in 2000 of the American Seamen’s Friend Society Sailors’ Home and Institute at 505-507 West Street, now the Jane Hotel, as well as the 2007 designation of the Keller Hotel at 150 Barrow Street. The latter is cited in its landmark designation report as “a significant reminder of the era when the Port of New York was one of the world’s busiest and the section of the Hudson River between Christopher and 23rd Streets was the heart of the busiest section of the Port of New York,” a description which applies no less to Seamen’s House.

What might replace the Seamen's House YMCA? Predictably, out-of-sight luxury condominiums for mainly absent and never seen residents, like 200 Eleventh Avenue. Its forbidding, anonymous and lifeless street presence says everything about these buildings' contribution to the community. The dead zone around it isn't even animated by residents walking through its lobby doors. When in town, they're driven onto a car elevator and ascend to "sky garages" adjoining their apartments, averting any risk of exposure to the community.

It's a tribute to Chelsea that its citizens can lament the closing of a local prison that kept inmates close to their outside support network. In the city at large, community introduction of social programs from halfway houses to public high schools routinely meets with agreement that they are necessary, just "not in my back yard," the source of the acronym, NIMBY. Pro-development types have co-opted this term, painting preservationists as NIMBYs against new construction. Their appropriation of it conveniently diverts accusations of self interest from themselves onto community advocates. They should know the label won't stick to Chelsea.

Mapping New York's Shoreline, 1609-2009

Henry Wellge's "Greatest New York", published by The New York Times Company in 1911 and featured in a new exhibition at the New York Public Library, places the city within a liquid embrace. Its foreground features the Jersey City waterfront. New Jersey commuters transferred from Central Railroad of New Jersey trains onto ferries bound for Lower Manhattan, tracing a ferry route first established in 1661. The New Jersey ferry slips are at center in the detail below.

Henry Wellge's "Greatest New York", published by The New York Times Company in 1911 and featured in a new exhibition at the New York Public Library, places the city within a liquid embrace. Its foreground features the Jersey City waterfront. New Jersey commuters transferred from Central Railroad of New Jersey trains onto ferries bound for Lower Manhattan, tracing a ferry route first established in 1661. The New Jersey ferry slips are at center in the detail below.

". . . I became aware of the old island that flowered once for Dutch sailors' eyes - a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees . . . had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder." - F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Henry Hudson and his crew may have sailed for the Dutch, but they were hired Englishmen, and whatever wonder they felt on beholding a new world would have been incidental to the job of finding an open sea route to Asia. What matters in Fitzgerald's case is the inspiration he found in the region's now 400 year old recorded history, and the water imagery it provided to what may well be the greatest page of American literature.

A nice contrast can be found in the pungent grittiness of Joseph Mitchell's 1951 essay, The Bottom of the Harbor: "The bulk of the water in New York Harbor is oily, dirty and germy. Men on the mud suckers, the big harbor dredges, like to say you could bottle it and sell it for poison. The bottom of the harbor is dirtier than the water. In most places it is covered with a blanket of sludge that is composed of silt, sewage, industrial wastes and clotted oil. The sludge is thickest in the slips along the Hudson, in the flats on the Jersey Side of the Upper Bay, and in backwaters such as Newtown Creek, Wallabout Bay, and the Gowanus Canal."

There's fuel for the imagination on all levels at the New York Public Library's new exhibition, Mapping New York's Shoreline, 1609-2009, from the dauntingly sketchy maps Hudson had to work with, setting out 400 years ago, to a 1905 New York Bay Pollution Commission map uneasily overlaying sewer outlets on shellfish beds.

". . . I became aware of the old island that flowered once for Dutch sailors' eyes - a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees . . . had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder." - F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Henry Hudson and his crew may have sailed for the Dutch, but they were hired Englishmen, and whatever wonder they felt on beholding a new world would have been incidental to the job of finding an open sea route to Asia. What matters in Fitzgerald's case is the inspiration he found in the region's now 400 year old recorded history, and the water imagery it provided to what may well be the greatest page of American literature.

A nice contrast can be found in the pungent grittiness of Joseph Mitchell's 1951 essay, The Bottom of the Harbor: "The bulk of the water in New York Harbor is oily, dirty and germy. Men on the mud suckers, the big harbor dredges, like to say you could bottle it and sell it for poison. The bottom of the harbor is dirtier than the water. In most places it is covered with a blanket of sludge that is composed of silt, sewage, industrial wastes and clotted oil. The sludge is thickest in the slips along the Hudson, in the flats on the Jersey Side of the Upper Bay, and in backwaters such as Newtown Creek, Wallabout Bay, and the Gowanus Canal."

There's fuel for the imagination on all levels at the New York Public Library's new exhibition, Mapping New York's Shoreline, 1609-2009, from the dauntingly sketchy maps Hudson had to work with, setting out 400 years ago, to a 1905 New York Bay Pollution Commission map uneasily overlaying sewer outlets on shellfish beds.

The 1907 Atlas of the Borough of Brooklyn by G.W. Bromley & Co. features names of Coney Island amusement parks and their rides, including Trip to the Moon, Canals of Venice and Thompson's Scenic Railway. The blue circle at left is labeled "Friede's Steel Globe Tower- 700 ft. high," testifying to the credibility of a proposal to build the world's first single-building resort. It was to have been the largest steel structure and the tallest and most voluminous building ever. As noted in Rem Koolhaas's riff on the project in Delirious New York, "by 1908 it is clear that the most impressive architectural project ever conceived is a fraud".

For anyone interested in maps or New York history, the show is a must-see. The maps range from crude to spectacular, and are accompanied by aerial views and period images the captions of which make for an effortless education in city history. One of the show's great lessons is the extent to which New York owes its existence and prominence to waters that extend far beyond its own 578 miles of waterfront. It's easy today to think of New York as an isolated spike driven into the globe, but as the show makes clear, its discovery, creation and rise were all about its place in the continuum of the world's waters.

The 1907 Atlas of the Borough of Brooklyn by G.W. Bromley & Co. features names of Coney Island amusement parks and their rides, including Trip to the Moon, Canals of Venice and Thompson's Scenic Railway. The blue circle at left is labeled "Friede's Steel Globe Tower- 700 ft. high," testifying to the credibility of a proposal to build the world's first single-building resort. It was to have been the largest steel structure and the tallest and most voluminous building ever. As noted in Rem Koolhaas's riff on the project in Delirious New York, "by 1908 it is clear that the most impressive architectural project ever conceived is a fraud".

For anyone interested in maps or New York history, the show is a must-see. The maps range from crude to spectacular, and are accompanied by aerial views and period images the captions of which make for an effortless education in city history. One of the show's great lessons is the extent to which New York owes its existence and prominence to waters that extend far beyond its own 578 miles of waterfront. It's easy today to think of New York as an isolated spike driven into the globe, but as the show makes clear, its discovery, creation and rise were all about its place in the continuum of the world's waters.

The six-inch wide maps of the Hudson River in the foreground are nine and twelve feet long. The longer one, at right, an 1846 "Panorama of the Hudson from New York to Albany," includes elevation views of topography and structures on each side of the River at a scale that might pass for accurate. The Hudson, and later the Erie Canal, linked New York to the heartland, enhancing its greatness as a port and helping propel it to the status of a world capital.

The exhibition runs through June 26, 2010. The Library is open from 10-6, Monday; 10-9, Tuesday and Wednesday; 10-6 Thursday through Saturday; and 1-5 on Sunday.

And while you're at it . . .

Join a tour of the Library conducted by docents, starting from the reception desk at 11AM and 2PM, Monday through Saturday, and at 2PM on Sunday. According to The Landmarks Preservation Commission's Guide to New York City Landmarks, "the main building for the New York Public Library, the design for which was won in competition by Carrère & Hastings, is perhaps the greatest masterpiece of Beaux-Arts architecture in the United States." The building's exterior is being restored in preparation for its 2011 centenary, with impressive results already visible on its Bryant Park façade.

The six-inch wide maps of the Hudson River in the foreground are nine and twelve feet long. The longer one, at right, an 1846 "Panorama of the Hudson from New York to Albany," includes elevation views of topography and structures on each side of the River at a scale that might pass for accurate. The Hudson, and later the Erie Canal, linked New York to the heartland, enhancing its greatness as a port and helping propel it to the status of a world capital.

The exhibition runs through June 26, 2010. The Library is open from 10-6, Monday; 10-9, Tuesday and Wednesday; 10-6 Thursday through Saturday; and 1-5 on Sunday.

And while you're at it . . .

Join a tour of the Library conducted by docents, starting from the reception desk at 11AM and 2PM, Monday through Saturday, and at 2PM on Sunday. According to The Landmarks Preservation Commission's Guide to New York City Landmarks, "the main building for the New York Public Library, the design for which was won in competition by Carrère & Hastings, is perhaps the greatest masterpiece of Beaux-Arts architecture in the United States." The building's exterior is being restored in preparation for its 2011 centenary, with impressive results already visible on its Bryant Park façade.

Mapping New York's Shoreline, 1609-2009

Henry Wellge's "Greatest New York", published by The New York Times Company in 1911 and featured in a new exhibition at the New York Public Library, places the city within a liquid embrace. Its foreground features the Jersey City waterfront. New Jersey commuters transferred from Central Railroad of New Jersey trains onto ferries bound for Lower Manhattan, tracing a ferry route first established in 1661. The New Jersey ferry slips are at center in the detail below.

Henry Wellge's "Greatest New York", published by The New York Times Company in 1911 and featured in a new exhibition at the New York Public Library, places the city within a liquid embrace. Its foreground features the Jersey City waterfront. New Jersey commuters transferred from Central Railroad of New Jersey trains onto ferries bound for Lower Manhattan, tracing a ferry route first established in 1661. The New Jersey ferry slips are at center in the detail below.

". . . I became aware of the old island that flowered once for Dutch sailors' eyes - a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees . . . had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder." - F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Henry Hudson and his crew may have sailed for the Dutch, but they were hired Englishmen, and whatever wonder they felt on beholding a new world would have been incidental to the job of finding an open sea route to Asia. What matters in Fitzgerald's case is the inspiration he found in the region's now 400 year old recorded history, and the water imagery it provided to what may well be the greatest page of American literature.

A nice contrast can be found in the pungent grittiness of Joseph Mitchell's 1951 essay, The Bottom of the Harbor: "The bulk of the water in New York Harbor is oily, dirty and germy. Men on the mud suckers, the big harbor dredges, like to say you could bottle it and sell it for poison. The bottom of the harbor is dirtier than the water. In most places it is covered with a blanket of sludge that is composed of silt, sewage, industrial wastes and clotted oil. The sludge is thickest in the slips along the Hudson, in the flats on the Jersey Side of the Upper Bay, and in backwaters such as Newtown Creek, Wallabout Bay, and the Gowanus Canal."

There's fuel for the imagination on all levels at the New York Public Library's new exhibition, Mapping New York's Shoreline, 1609-2009, from the dauntingly sketchy maps Hudson had to work with, setting out 400 years ago, to a 1905 New York Bay Pollution Commission map uneasily overlaying sewer outlets on shellfish beds.

". . . I became aware of the old island that flowered once for Dutch sailors' eyes - a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees . . . had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder." - F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Henry Hudson and his crew may have sailed for the Dutch, but they were hired Englishmen, and whatever wonder they felt on beholding a new world would have been incidental to the job of finding an open sea route to Asia. What matters in Fitzgerald's case is the inspiration he found in the region's now 400 year old recorded history, and the water imagery it provided to what may well be the greatest page of American literature.

A nice contrast can be found in the pungent grittiness of Joseph Mitchell's 1951 essay, The Bottom of the Harbor: "The bulk of the water in New York Harbor is oily, dirty and germy. Men on the mud suckers, the big harbor dredges, like to say you could bottle it and sell it for poison. The bottom of the harbor is dirtier than the water. In most places it is covered with a blanket of sludge that is composed of silt, sewage, industrial wastes and clotted oil. The sludge is thickest in the slips along the Hudson, in the flats on the Jersey Side of the Upper Bay, and in backwaters such as Newtown Creek, Wallabout Bay, and the Gowanus Canal."

There's fuel for the imagination on all levels at the New York Public Library's new exhibition, Mapping New York's Shoreline, 1609-2009, from the dauntingly sketchy maps Hudson had to work with, setting out 400 years ago, to a 1905 New York Bay Pollution Commission map uneasily overlaying sewer outlets on shellfish beds.

The 1907 Atlas of the Borough of Brooklyn by G.W. Bromley & Co. features names of Coney Island amusement parks and their rides, including Trip to the Moon, Canals of Venice and Thompson's Scenic Railway. The blue circle at left is labeled "Friede's Steel Globe Tower- 700 ft. high," testifying to the credibility of a proposal to build the world's first single-building resort. It was to have been the largest steel structure and the tallest and most voluminous building ever. As noted in Rem Koolhaas's riff on the project in Delirious New York, "by 1908 it is clear that the most impressive architectural project ever conceived is a fraud".

For anyone interested in maps or New York history, the show is a must-see. The maps range from crude to spectacular, and are accompanied by aerial views and period images the captions of which make for an effortless education in city history. One of the show's great lessons is the extent to which New York owes its existence and prominence to waters that extend far beyond its own 578 miles of waterfront. It's easy today to think of New York as an isolated spike driven into the globe, but as the show makes clear, its discovery, creation and rise were all about its place in the continuum of the world's waters.

The 1907 Atlas of the Borough of Brooklyn by G.W. Bromley & Co. features names of Coney Island amusement parks and their rides, including Trip to the Moon, Canals of Venice and Thompson's Scenic Railway. The blue circle at left is labeled "Friede's Steel Globe Tower- 700 ft. high," testifying to the credibility of a proposal to build the world's first single-building resort. It was to have been the largest steel structure and the tallest and most voluminous building ever. As noted in Rem Koolhaas's riff on the project in Delirious New York, "by 1908 it is clear that the most impressive architectural project ever conceived is a fraud".

For anyone interested in maps or New York history, the show is a must-see. The maps range from crude to spectacular, and are accompanied by aerial views and period images the captions of which make for an effortless education in city history. One of the show's great lessons is the extent to which New York owes its existence and prominence to waters that extend far beyond its own 578 miles of waterfront. It's easy today to think of New York as an isolated spike driven into the globe, but as the show makes clear, its discovery, creation and rise were all about its place in the continuum of the world's waters.

The six-inch wide maps of the Hudson River in the foreground are nine and twelve feet long. The longer one, at right, an 1846 "Panorama of the Hudson from New York to Albany," includes elevation views of topography and structures on each side of the River at a scale that might pass for accurate. The Hudson, and later the Erie Canal, linked New York to the heartland, enhancing its greatness as a port and helping propel it to the status of a world capital.

The exhibition runs through June 26, 2010. The Library is open from 10-6, Monday; 10-9, Tuesday and Wednesday; 10-6 Thursday through Saturday; and 1-5 on Sunday.

And while you're at it . . .

Join a tour of the Library conducted by docents, starting from the reception desk at 11AM and 2PM, Monday through Saturday, and at 2PM on Sunday. According to The Landmarks Preservation Commission's Guide to New York City Landmarks, "the main building for the New York Public Library, the design for which was won in competition by Carrère & Hastings, is perhaps the greatest masterpiece of Beaux-Arts architecture in the United States." The building's exterior is being restored in preparation for its 2011 centenary, with impressive results already visible on its Bryant Park façade.

The six-inch wide maps of the Hudson River in the foreground are nine and twelve feet long. The longer one, at right, an 1846 "Panorama of the Hudson from New York to Albany," includes elevation views of topography and structures on each side of the River at a scale that might pass for accurate. The Hudson, and later the Erie Canal, linked New York to the heartland, enhancing its greatness as a port and helping propel it to the status of a world capital.

The exhibition runs through June 26, 2010. The Library is open from 10-6, Monday; 10-9, Tuesday and Wednesday; 10-6 Thursday through Saturday; and 1-5 on Sunday.

And while you're at it . . .

Join a tour of the Library conducted by docents, starting from the reception desk at 11AM and 2PM, Monday through Saturday, and at 2PM on Sunday. According to The Landmarks Preservation Commission's Guide to New York City Landmarks, "the main building for the New York Public Library, the design for which was won in competition by Carrère & Hastings, is perhaps the greatest masterpiece of Beaux-Arts architecture in the United States." The building's exterior is being restored in preparation for its 2011 centenary, with impressive results already visible on its Bryant Park façade.

Nouvel's Tower Verre Not the Only Vision in the Hearing Room

Jean Nouvel presented his design for the new MoMA tower in a public hearing at the City Planning Commission yesterday. Calling it "zee meezing peez of zee pizzle", Nouvel made a case for the spike of his "Tower Verre" as a natural fit within the sawtooth rhythm of Manhattan's skyline. Describing its lack of bulk and the way it leans back from the street and attenuates into the sky as resulting in a "modest" building, Nouvel also placed it within the historic context of the "needle" like buildings rendered by Hugh Ferris. It's hard to sell a building that exceeds its as-of-right zoning height by 161 feet as contextual, but Nouvel clearly had a receptive audience in the Planning Commission. The concern expressed for preserving the building's poetically tapering peak was reminiscent of the 1980s rage for skyscrapers-with-tops.

Rendering of Jean Nouvel's Tower Verre

Nouvel's tower has received praise from critics and criticism from community groups, even as Hines, its giant international developer, has advanced the project through review processes and closer to realization. MoMA sold the site to Hines for $125 million in a deal that will cede 39,500 square feet of space in the new building back to the museum for galleries. MoMA director Glenn Lowry pointed out in the hearing that the double-height second floor of the new tower will be especially useful to the museum for exhibition of large works by sculptors like Richard Serra and Martin Puryear. Opponents of the tower have generally addressed its great height. Community members at yesterday's hearings called it colossal, outrageously tall, and - of course - an oversized phallus.

Hugh Ferriss's rendering of William Van Alen's Chrysler Building

It's been noted that Nouvel's 82-story building will exceed the height of the Chrysler Building, an icon that in some ways haunts the discussion. Perhaps the ultimate in pointy skyscrapers, the Chrysler Building was rendered by Ferriss approaching completion, its top still an open steel framework through which daylight can be seen. Nouvel spoke of his building yesterday as a "skeleton" and "also a dream", balancing materiality and immateriality. "It has to disappear into the sky", he said, in terms that seem to have Ferriss's incomplete Chrysler in mind. While Nouvel's renderings don't particularly exploit this characteristic, the building's framing suggests how it might be achieved at the peak.

Tower Verre's framing model suggests how its top might be dematerialized by penetrating light.

The dissolving quality that Nouvel described would mitigate somewhat the impact of what is, after all, not the Chrysler Building but a nearly quarter-mile tall glass sheath. This hermetic quality and the building's height are behind architect John Beckmann's denunciation of it at yesterday's hearing as a "glass spike driven into the heart of New York City". Beckmann proceeded to put his money where his mouth is by presenting an alternate scheme that satisfies the same program in thirty fewer stories and in a more permeable form.

An alternate MoMA tower proposal by architect John Beckmann and his firm, Axis Mundi

With open arcades at sidewalk level, and seemingly composed entirely of nooks and crannies, Beckmann's building at first appears to be riding the trend for jiggled-box compositions like Herzog & de Meuron's 56 Leonard Street project, but on closer inspection has a more open character, with through-building openings aloft, and elevated gardens, similar to Moshe Safdie's Habitat '67, as well as exterior stairways. This upper level sponginess may not allow any greater access to the man on the street, but it invites imaginative penetration of the sort architect Robert Yudell described as the antidote to the curtain-wall skyscraper, of which he wrote: "We can neither measure ourselves against it nor imagine a bodily participation. Our bodily response is reduced to little more than a craned head, wide eyes, and perhaps an open jaw in appreciation of some magnificent height or some elegantly prescribed mullion detailing. Compare this with a 1920s ziggurat skyscraper such as the Chrysler Building. Here we have not only the vertical differentiation of the building but chunky setbacks which conjure landscapes or grand stairways. We can imagine scaling, leaping, and occupying its surfaces and interstices. Even the cheap and efficient stepped-back curtain-wall buildings erected along New York's City's Park Avenue in the 1950s and 1960s provide us with some form of cubic landscape."*

Robert Yudell illustrated his essay criticizing curtain wall skyscrapers with "King's Dream of New York", a 1908 fantasy rendering that shows a population almost hyperactively engaged with its city.

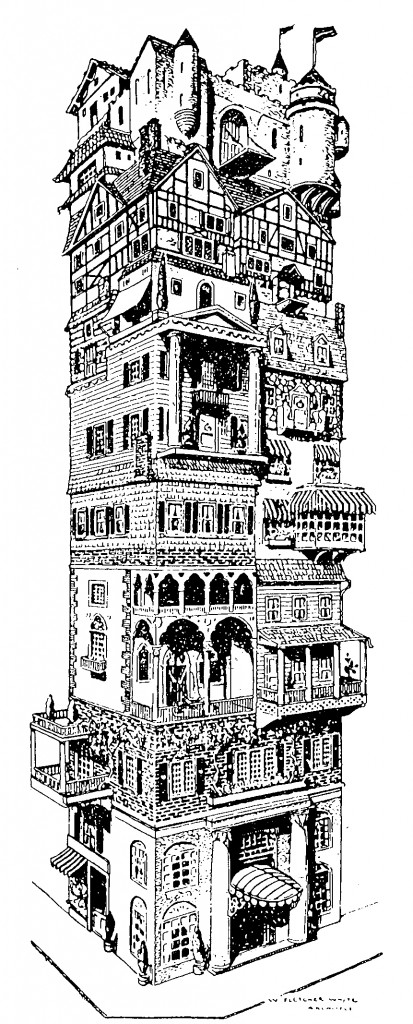

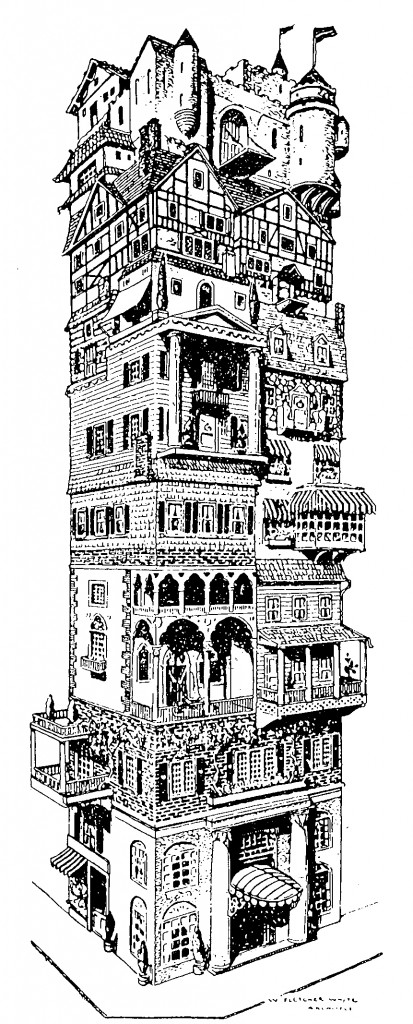

Rem Koolhaas used this seminal 1909 Life magazine cartoon in "Delirious New York".

A year later, Rem Koolhaas would illustrate Delirious New York with "King's Dream of New York" and a 1909 Life magazine cartoon that shows conventional houses stacked one per floor on an open steel skyscraper frame. It is this latter image that Koolhaas mines for a rich payload of ideology. Calling it "a theorem that describes the ideal performance of the Skyscraper", Koolhaas says: "The structure is a whole exactly to the extent that the individuality of the platforms is preserved and exploited, that its success should be measured by the degree to which the structure frames their coexistence without interfering with their destinies. The building becomes a stack of individual privacies. . . Villas may go up and collapse, other facilities may replace them, but that will not affect the framework. . . An unforeseeable and unstable combination of simultaneous activities . . . makes architecture less an act of foresight than before and planning an act of only limited prediction." ** The same cartoon directly inspired James Wines and his firm SITE's 1980s Highrise of Homes project, which sought to reconcile the "overbearing" highrise with a "flexible and responsive habitat for urban dwellers".***

SITE's Highrise of Homes

As Beckmann told ArchiTakes yesterday, the exteriors of individual units in his tower could be customized by residents for personal expression and flexibility of use. There's an irresistible appeal both in the individual liberation of this and in the idea of the building as an uncontrolled rotating exhibit attached to the museum. The resulting collage would respond to popular impulses that have been around in cartoons for a century, and which thrive in today's art world. Beckmann's thought provoking alternative won't derail Nouvel's tower, but it substantiates his criticism that there are other ways. It's also worth remembering the power of a picture, as witnessed by Ferriss's influence on Nouvel and an old cartoon's on Koolhaas and his entire orbit. Architecture in New York could use more of the grassroots initiative Beckmann has shown and more of the debate he hopes to inspire.

This 1920 cartoon also inspired SITE's Highrise of Homes.

Dionisio Gonzalez's "Nova Heliopolis II" might have taken inspiration from the cartoon above. Artists like Gonzalez, Laura S. Kicey and Kobas Laksa are among many who depict collage-buildings.

* Body, Memory and Architecture,by Kent C. Bloomer, Charles W. Moore and Robert J. Yudell, Yale, 1977 (pp.61-64)

** Delirious New York, by Rem Koolhaas, Oxford, 1978 (pp.69-70)

*** Highrise of Homes, by SITE, Rizzoli, 1982 (p.11)

Nouvel's Tower Verre Not the Only Vision in the Hearing Room

Jean Nouvel presented his design for the new MoMA tower in a public hearing at the City Planning Commission yesterday. Calling it "zee meezing peez of zee pizzle", Nouvel made a case for the spike of his "Tower Verre" as a natural fit within the sawtooth rhythm of Manhattan's skyline. Describing its lack of bulk and the way it leans back from the street and attenuates into the sky as resulting in a "modest" building, Nouvel also placed it within the historic context of the "needle" like buildings rendered by Hugh Ferris. It's hard to sell a building that exceeds its as-of-right zoning height by 161 feet as contextual, but Nouvel clearly had a receptive audience in the Planning Commission. The concern expressed for preserving the building's poetically tapering peak was reminiscent of the 1980s rage for skyscrapers-with-tops.

Rendering of Jean Nouvel's Tower Verre

Nouvel's tower has received praise from critics and criticism from community groups, even as Hines, its giant international developer, has advanced the project through review processes and closer to realization. MoMA sold the site to Hines for $125 million in a deal that will cede 39,500 square feet of space in the new building back to the museum for galleries. MoMA director Glenn Lowry pointed out in the hearing that the double-height second floor of the new tower will be especially useful to the museum for exhibition of large works by sculptors like Richard Serra and Martin Puryear. Opponents of the tower have generally addressed its great height. Community members at yesterday's hearings called it colossal, outrageously tall, and - of course - an oversized phallus.

Hugh Ferriss's rendering of William Van Alen's Chrysler Building

It's been noted that Nouvel's 82-story building will exceed the height of the Chrysler Building, an icon that in some ways haunts the discussion. Perhaps the ultimate in pointy skyscrapers, the Chrysler Building was rendered by Ferriss approaching completion, its top still an open steel framework through which daylight can be seen. Nouvel spoke of his building yesterday as a "skeleton" and "also a dream", balancing materiality and immateriality. "It has to disappear into the sky", he said, in terms that seem to have Ferriss's incomplete Chrysler in mind. While Nouvel's renderings don't particularly exploit this characteristic, the building's framing suggests how it might be achieved at the peak.

Tower Verre's framing model suggests how its top might be dematerialized by penetrating light.

The dissolving quality that Nouvel described would mitigate somewhat the impact of what is, after all, not the Chrysler Building but a nearly quarter-mile tall glass sheath. This hermetic quality and the building's height are behind architect John Beckmann's denunciation of it at yesterday's hearing as a "glass spike driven into the heart of New York City". Beckmann proceeded to put his money where his mouth is by presenting an alternate scheme that satisfies the same program in thirty fewer stories and in a more permeable form.

An alternate MoMA tower proposal by architect John Beckmann and his firm, Axis Mundi

With open arcades at sidewalk level, and seemingly composed entirely of nooks and crannies, Beckmann's building at first appears to be riding the trend for jiggled-box compositions like Herzog & de Meuron's 56 Leonard Street project, but on closer inspection has a more open character, with through-building openings aloft, and elevated gardens, similar to Moshe Safdie's Habitat '67, as well as exterior stairways. This upper level sponginess may not allow any greater access to the man on the street, but it invites imaginative penetration of the sort architect Robert Yudell described as the antidote to the curtain-wall skyscraper, of which he wrote: "We can neither measure ourselves against it nor imagine a bodily participation. Our bodily response is reduced to little more than a craned head, wide eyes, and perhaps an open jaw in appreciation of some magnificent height or some elegantly prescribed mullion detailing. Compare this with a 1920s ziggurat skyscraper such as the Chrysler Building. Here we have not only the vertical differentiation of the building but chunky setbacks which conjure landscapes or grand stairways. We can imagine scaling, leaping, and occupying its surfaces and interstices. Even the cheap and efficient stepped-back curtain-wall buildings erected along New York's City's Park Avenue in the 1950s and 1960s provide us with some form of cubic landscape."*

Robert Yudell illustrated his essay criticizing curtain wall skyscrapers with "King's Dream of New York", a 1908 fantasy rendering that shows a population almost hyperactively engaged with its city.

Rem Koolhaas used this seminal 1909 Life magazine cartoon in "Delirious New York".

A year later, Rem Koolhaas would illustrate Delirious New York with "King's Dream of New York" and a 1909 Life magazine cartoon that shows conventional houses stacked one per floor on an open steel skyscraper frame. It is this latter image that Koolhaas mines for a rich payload of ideology. Calling it "a theorem that describes the ideal performance of the Skyscraper", Koolhaas says: "The structure is a whole exactly to the extent that the individuality of the platforms is preserved and exploited, that its success should be measured by the degree to which the structure frames their coexistence without interfering with their destinies. The building becomes a stack of individual privacies. . . Villas may go up and collapse, other facilities may replace them, but that will not affect the framework. . . An unforeseeable and unstable combination of simultaneous activities . . . makes architecture less an act of foresight than before and planning an act of only limited prediction." ** The same cartoon directly inspired James Wines and his firm SITE's 1980s Highrise of Homes project, which sought to reconcile the "overbearing" highrise with a "flexible and responsive habitat for urban dwellers".***

SITE's Highrise of Homes

As Beckmann told ArchiTakes yesterday, the exteriors of individual units in his tower could be customized by residents for personal expression and flexibility of use. There's an irresistible appeal both in the individual liberation of this and in the idea of the building as an uncontrolled rotating exhibit attached to the museum. The resulting collage would respond to popular impulses that have been around in cartoons for a century, and which thrive in today's art world. Beckmann's thought provoking alternative won't derail Nouvel's tower, but it substantiates his criticism that there are other ways. It's also worth remembering the power of a picture, as witnessed by Ferriss's influence on Nouvel and an old cartoon's on Koolhaas and his entire orbit. Architecture in New York could use more of the grassroots initiative Beckmann has shown and more of the debate he hopes to inspire.

This 1920 cartoon also inspired SITE's Highrise of Homes.

Dionisio Gonzalez's "Nova Heliopolis II" might have taken inspiration from the cartoon above. Artists like Gonzalez, Laura S. Kicey and Kobas Laksa are among many who depict collage-buildings.

* Body, Memory and Architecture,by Kent C. Bloomer, Charles W. Moore and Robert J. Yudell, Yale, 1977 (pp.61-64)

** Delirious New York, by Rem Koolhaas, Oxford, 1978 (pp.69-70)

*** Highrise of Homes, by SITE, Rizzoli, 1982 (p.11)