Mythic New York

The Future Still Needs the Gimbels Skybridge

For nearly a century, the Gimbels skybridge has served as a kind of gatehouse announcing Pennsylvania Station on the next block west. Few would guess that its interior was once continuous with the station's. The bridge will disappear if plans for the Empire Station Complex proceed. This would be a terrible loss. It is by far the most prominent aerial bridge from an era when the rest of the world looked to New York as the skyscraping, multi-level City of the Future—the crowning example of a phenomenon that influenced modern architecture and still captivates and inspires.

According to a 2014 New York Times piece by Christopher Gray, the bridge was built in 1926 when the Gimbels department store acquired the Cuyler Building across West 32nd Street and hired Shreve & Lamb—soon to be Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, and architects of the nearby Empire State Building—to connect offices in the building to the main store. Gray wrote, "The architects’ design was a no-holds-barred exemplar of the pedestrian bridge, a triplex skywalk with broad windows and magnificent copper cladding."

Gray observed that, "Although there is classical ornament, such as pilasters and coffers, the flat, machinelike character of the material suggests Art Deco, then barely emergent in the United States." He noted that in 1982 The New Yorker called the bridge "the Chartres of aerial tunnelry."

A 1924 skybridge across 33rd Street, also by Shreve & Lamb, linked the other side of Gimbels to the former Saks store. (It is shown being demolished in 1966.) When Saks moved to its Fifth Avenue location in 1922, Gimbels took over the old building, operating it as Saks-34th Street. The tamely classical Gimbels-Saks bridge shows how far its architects' style stepped into the future by the time of the Gimbels-annex bridge two years later.

The two Gimbels bridges were part of a layered transportation arrangement for which New York was world famous. The streets beneath these bridges passed in turn over the subway, accessible through the Gimbels store. A pedestrian tunnel also connected Gimbels to Pennsylvania Station, passing beneath the Hotel Pennsylvania and Seventh Avenue. One could have entered this enclosed system through Gimbels, its annex, or Saks-34th Street and next stepped outdoors in Chicago, having accessed Penn Station through the connecting bridge-tunnel-building network.

The Hotel Pennsylvania and the Governor Clinton (now Stewart) Hotel were also part of this network, linked to the station by tunnels under Seventh Avenue. An out-of-towner could arrive by train at Penn station, get a haircut in its barber shop, buy underwear in Gimbels' bargain basement and a suit at Saks, wear them to dinner in a station or hotel restaurant, listen to a big band in the Hotel Pennsylvania's Café Rouge, sleep in one of the hotels' thousands of beds, breakfast in the station's cafeteria, and return home—without ever stepping outdoors. The linked buildings provided enough services to amount to a city within a city. Like their contemporary mixed-use complex at Grand Central Terminal, they anticipated the megastructure movement of the 1960s and 70s which melded buildings to transportation and aspired to place the full range of urban functions under one roof. In his 1976 book, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, Reyner Banham wrote that "patriotic Gothamites eager to claim the concept as a New York invention" could point to Penn Station, Grand Central, and Rockefeller Center. The movement had peaked by the time of his writing but it moved architecture's needle. It's ideas still guide leading architectural theorists like Rem Koolhaas and Steven Holl.

Shreve, Lamb & Harmon's Art Deco Empire State Building is seen beyond their proto-Deco Gimbels skybridge which Christopher Gray called "one of the city's great works of metal." Both were designed in the late 1920s, a mythic period of concentrated activity when the exuberance of New York architecture reached a crescendo and many of the city's best-loved and most defining works were produced. Both structures were the apotheosis of their type, the aerial bridge and skyscraper, which in combination dominated early-twentieth-century visions of cities to come. When Kuala Lumpur's 1998 Petronas Towers followed in the Empire State Building's footsteps as the world's tallest buildings, their linking skybridge carried the DNA of this imagery.

The Empire State Building's top, another of the city's great works of metal, was touted as a mooring mast for zeppelins. Impractical for this use, its real purpose was to contribute to the building's record-setting height. The mooring-mast claim was telling, though. The skies of urban fantasies inspired by New York were alive with airships. It's as if the Empire State Building's designers felt obliged to deliver. Like skybridges and skyscrapers, lighter-than-air vehicles resisted gravity. These ingredients mixed to create popular urban visions that promised liberation from an earthbound existence.

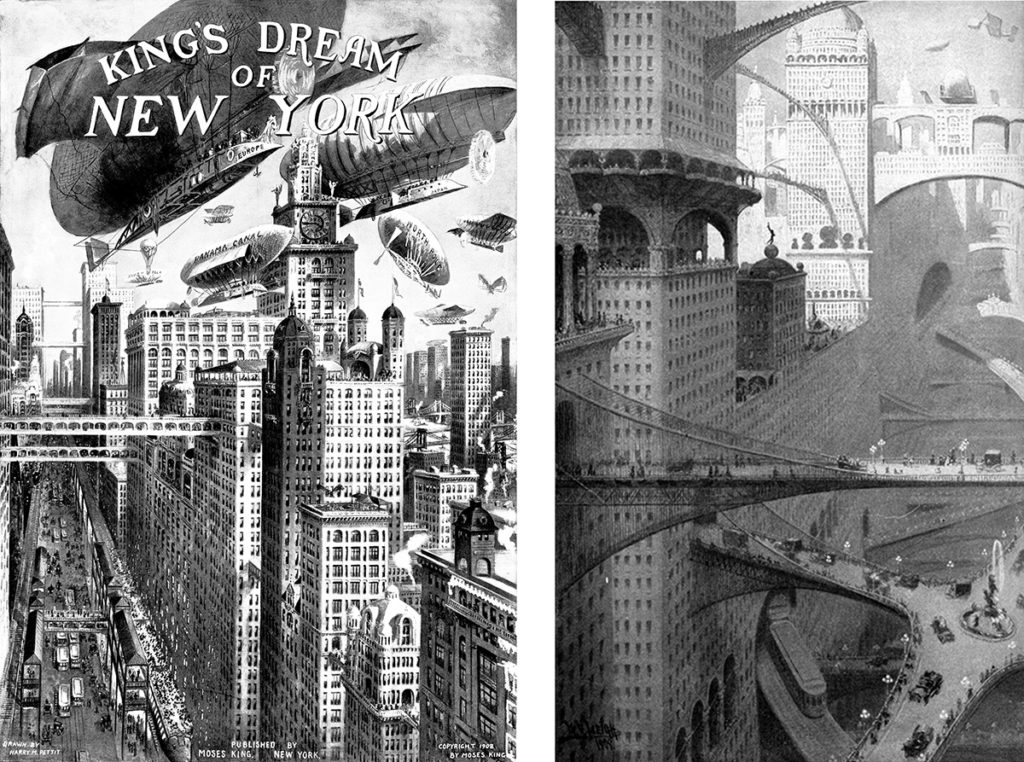

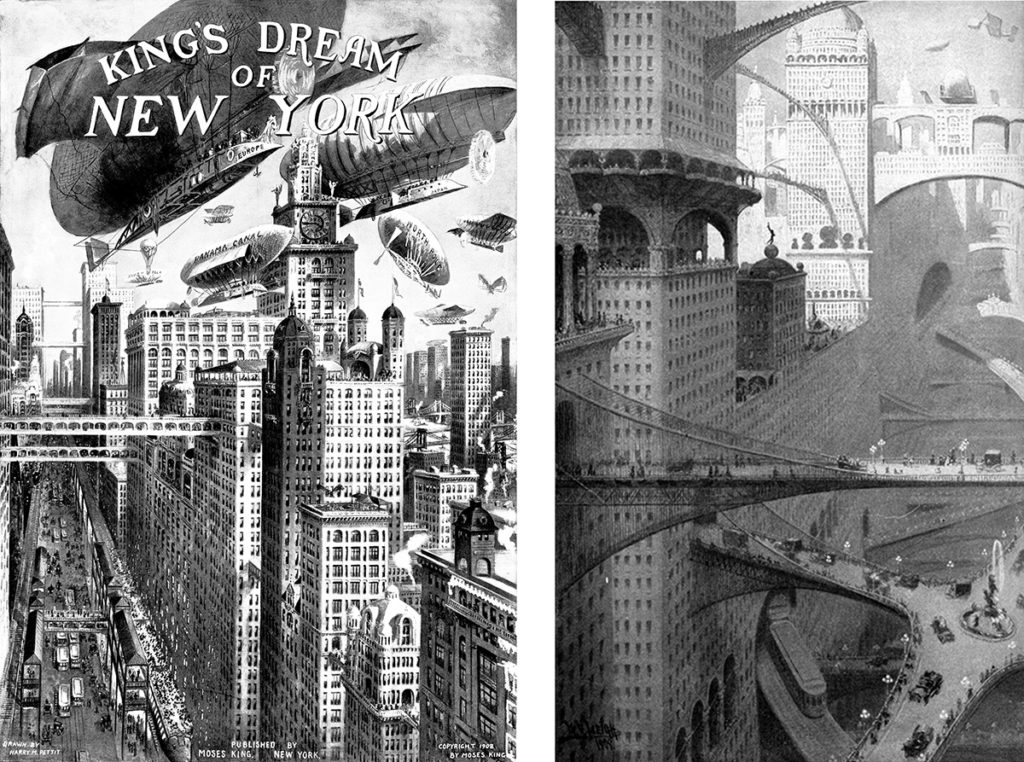

Images like Harry M. Pettit's rendering for Moses King’s guidebook, Views of New York, and William Robinson Leigh's painting, "Visionary City," both from 1908, exaggerated New York's towers and aerial pathways to project the future. Practicality aside, these cityscapes looked thrilling to inhabit. Aerial bridges allow people to magically step through building façades and cross streets in the air. Space takes on dizzying visual depth and unprecedented three-dimensional navigability. All of this plays to our fundamental condition as mobile bodies in space possessed of free will. The immersive motion in these images coincided with the advent of popular movies which also appealed to the modern appetite for speed, daring, and excitement.

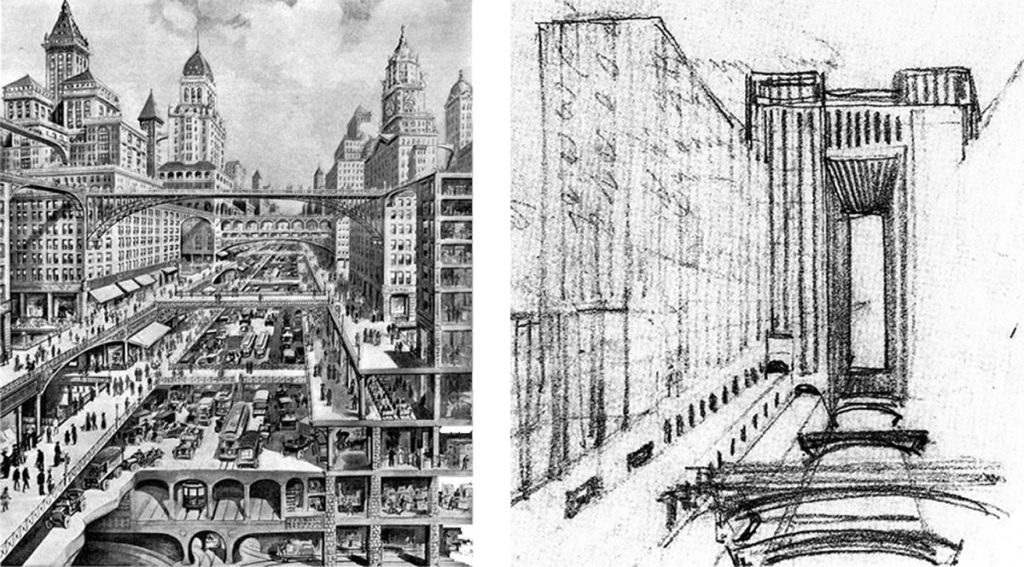

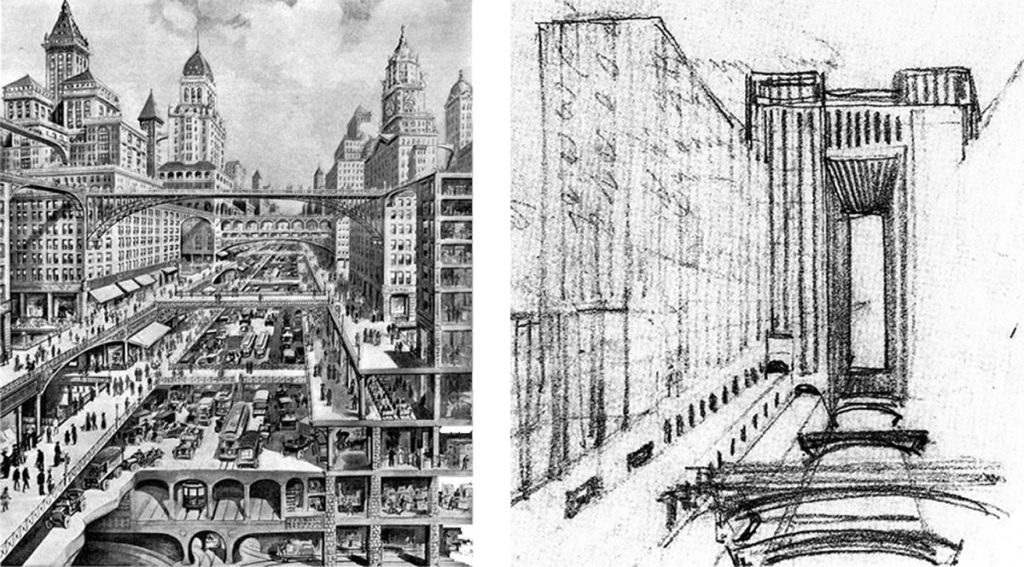

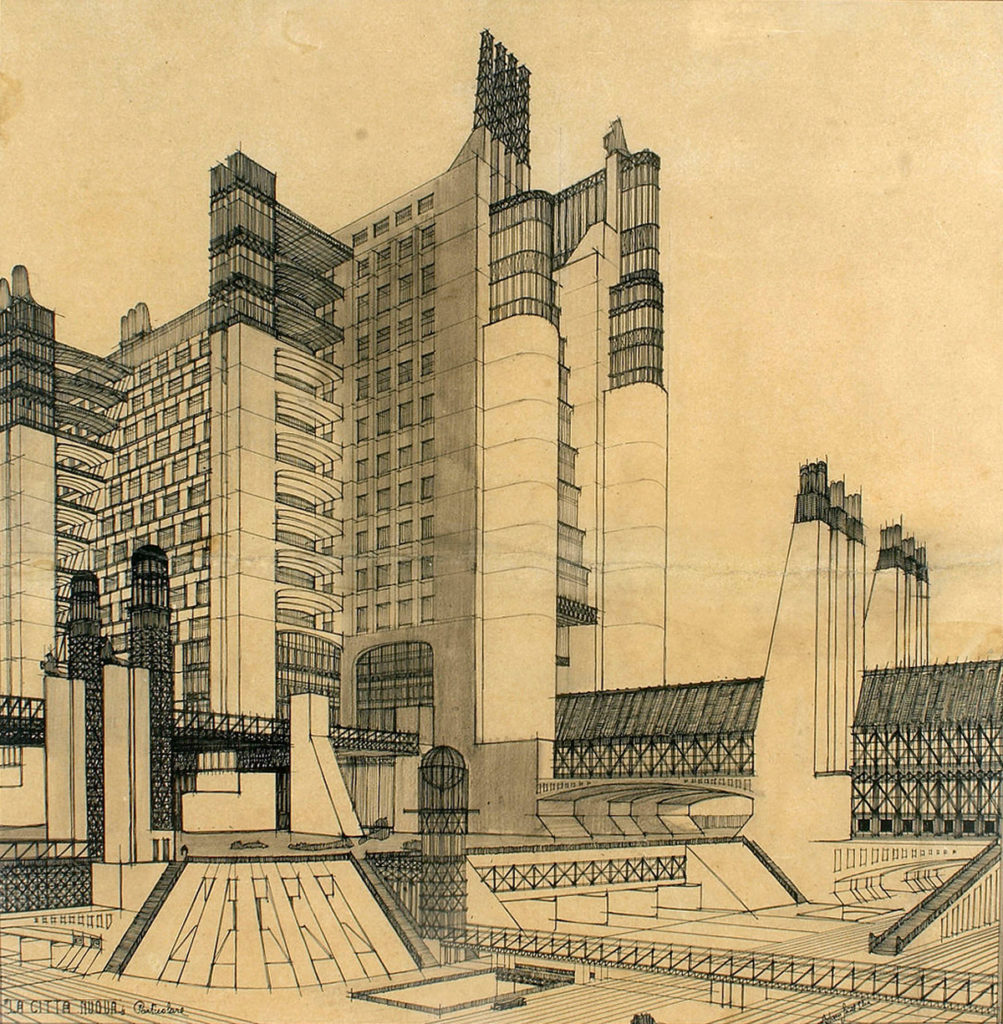

The illustration at left was featured on the cover of Scientific American in 1913 and reproduced the same year as "The Circulation of the Future and the Cloudscrapers of New York" in the Milanese magazine L'Illustrazione Italiana. Such images inspired the influential Milan-based Italian Futurist movement, as seen in Antonio Sant'Elia's study for his project La Città Nuova (The New City) at right.

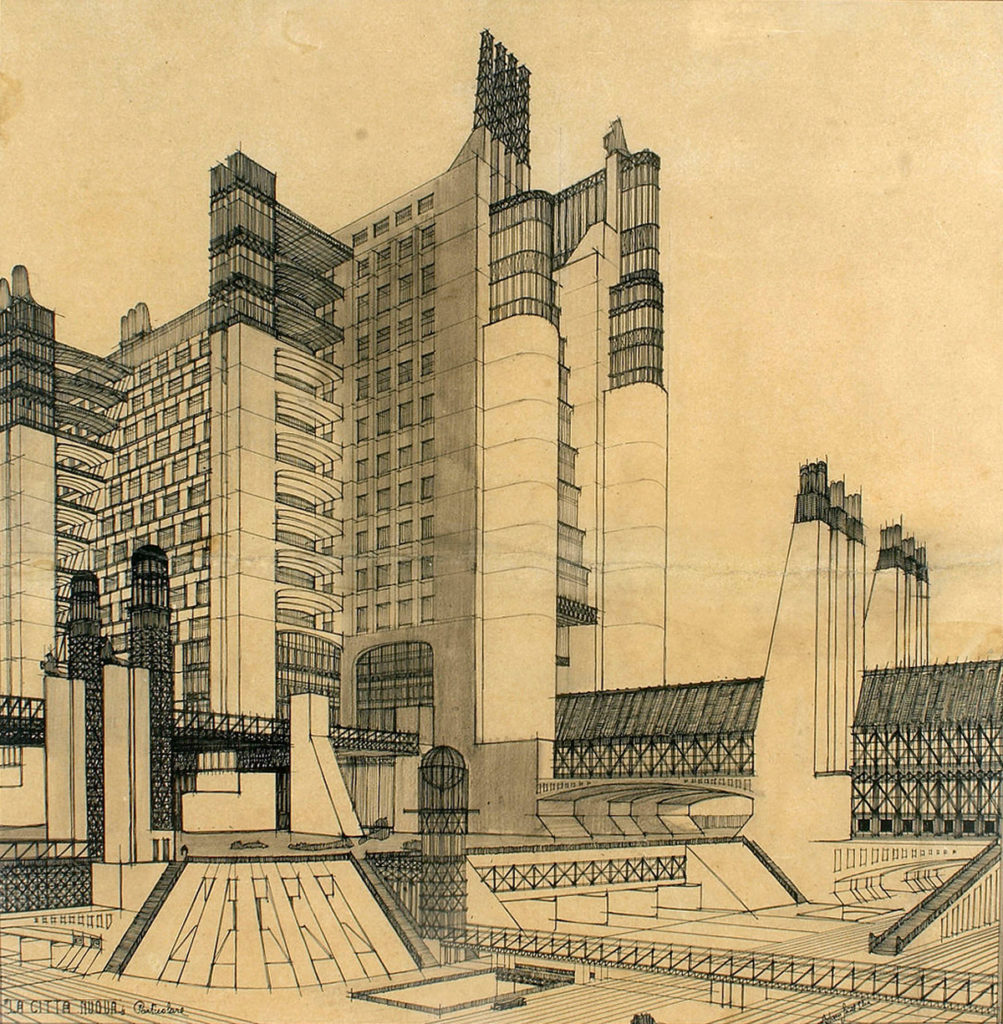

This 1914 rendering is Sant'Elia's most fully developed rendering of La Città Nuova. (He was killed two years later in World War One at just 28.) Bridges, overpasses, and transportation systems aren't tacked onto the static buildings of a traditional city, but used as the building blocks of a new kind of dynamic, city-scale structure that jettisons architectural history.

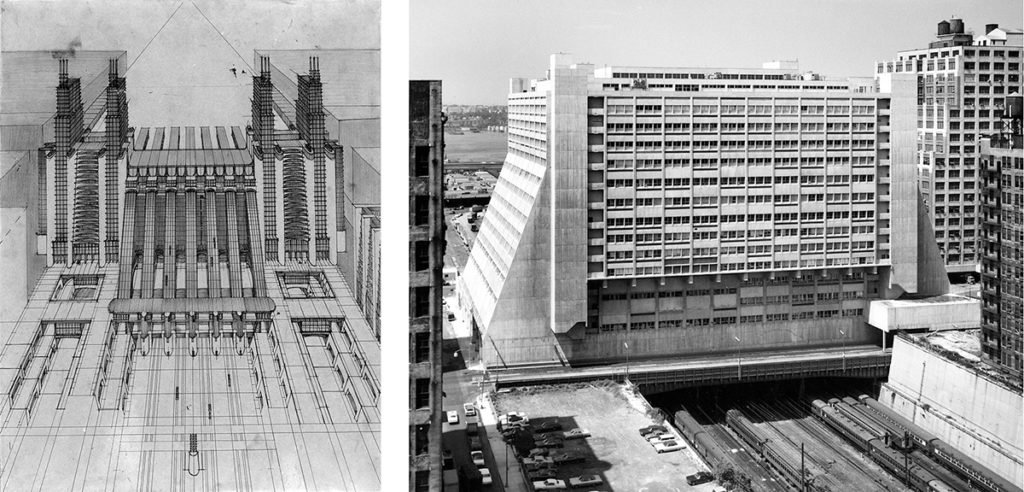

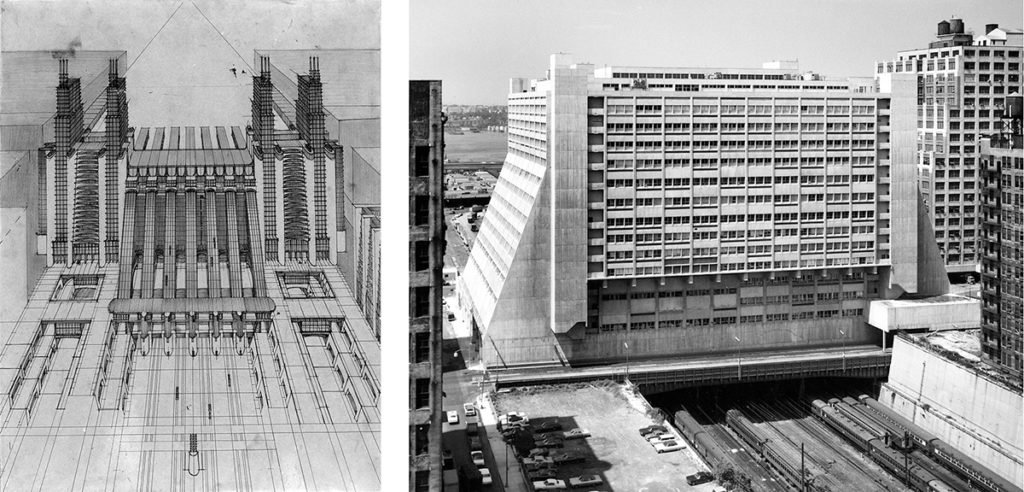

In the 1914 image at left, Sant'Elia imagined a station for airplanes and trains with funiculars. Manhattan's Westyard Distribution Center at right was designed by Davis Brody and opened in 1969—one of countless buildings around the world influenced by Sant'Elia's unbuilt body of work. The historic photo shows Westyard straddling the West Side Rail Yards. It has been renovated as Five Manhattan West. The block of the railyard beyond it has been decked over and developed as Hudson Yards. The block in the foreground has been decked over and developed as part of Midtown West, with a central pedestrian mall running from Five Manhattan West to Ninth Avenue directly opposite the west entrance of the new Moynihan Train Hall. The mall's axis resumes on the other side of Moynihan Train Hall and Penn Station as 32nd Street, passing directly under the Gimbels skybridge like a through-line of architectural history.

Five Manhattan West, formerly Westyard, is seen with its newly enhanced dynamic diagonals at upper right in this rendering of the High Line's planned Moynihan Connector. The pedestrian bridge will link a tree-covered extension of the High Line's spur to the new Manhattan West mall (a right turn just past the pink-flowering trees) which approaches the Train Hall. Another connector will link the north leg of the High Line to the west terrace of the Javits Center and a long-planned but never-built pedestrian bridge over the West Side Highway to Hudson River Park. Together with the High Line itself, this pedestrian network, raised above street traffic, may be one of the closest things ever built to those layered-city magazine fantasies that inspired Sant'Elia and the Futurists.

Fritz Lang said his classic 1927 film Metropolis was inspired by a 1924 visit to New York. It was also clearly influenced by futuristic visions of New York and Sant'Elia's projects, as have been science fiction movies from Blade Runner to Brazil to The Fifth Element, the latter featuring a future New York dense with skybridges and flying taxis. The richly activated three-dimensionality of early visions on paper is inherently cinematic, as witnessed by countless cinematic shoot-outs on the monkey-bar catwalks and ladders of abandoned warehouses. Forward-looking architecture naturally shares territory in the future with science fiction; Frank Lloyd Wright's 1924 Ennis House was still out-there enough to portray 2019 Los Angeles in Blade Runner.

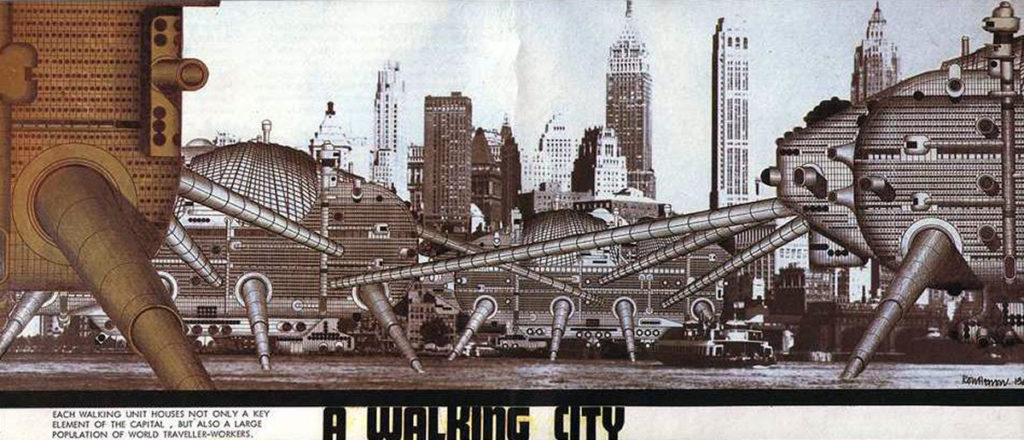

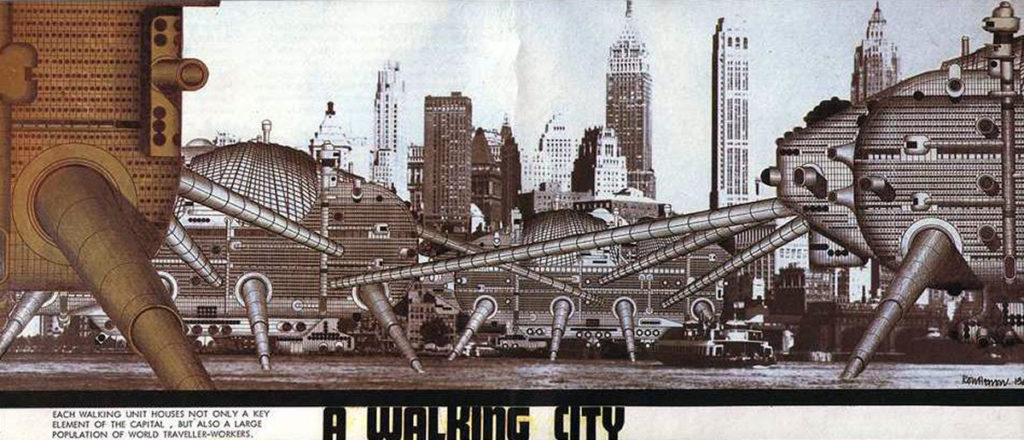

This rendering of the 1963 Walking City project by the avant-garde architectural group Archigram is captioned: "Each walking unit houses not only a key element of the capital, but also a large population of world-traveler-workers." With its leg-like bridges, the Walking City is in the futuristic skybridge-city tradition. It is also in the city-within-a-city tradition of interconnected buildings forming self-contained complexes like the ones centered on Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal. The scheme does the motion-infused city one better—the city itself moves. Reyner Banham included this image in Megastructure, writing of its units: "Their location here in the East River, with the towers of Manhattan in the background, suggests a deliberate challenge to older visions of the future."

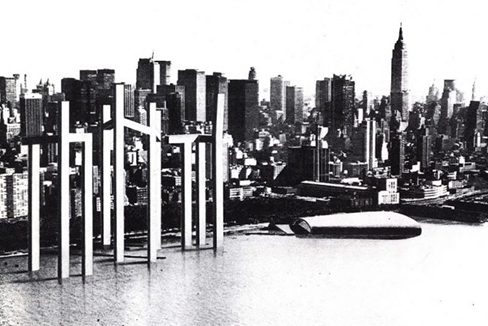

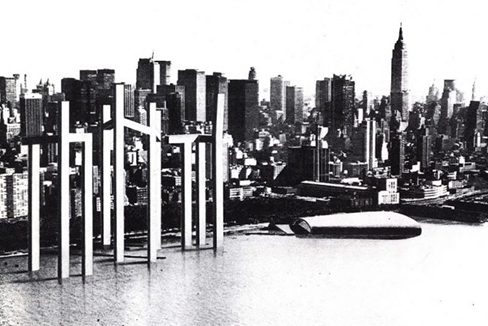

Freed from the land and knee-deep in the Hudson against a backdrop of midtown skyscrapers, Architect Steven Holl's 1990 Parallax Towers project mirrors Archigram's Walking City on the opposite side of Manhattan. Its "hybrid buildings" with diverse functions would be connected both underwater and by skybridges.

Holl's 2009 Linked Hybrid project in Beijing shows that his Parallax Towers scheme was far from a pipe dream. Its eight towers linked by eight bridges house 2,500 residents and recall Matisse's ring of dancers clasping hands—an apt metaphor for Holl's intent to un-silo residents, generate random relationships, and "express a collective aspiration." (They also recall Gimbels when it had a bridge on each side like outstretched arms.) The skybridges contain a swimming pool, fitness room, café, and gallery. Holl's description places the complex in the best cinematic, layered-city, proto-megastructure New York tradition:

As a "city within a city" the new place has a filmic urban experience of space; around, over and through multifaceted spatial layers. A three-dimensional public urban space, the project has programs that vary from commercial, residential, and educational to recreational.

In this dazzling project, New York's early skybridges reverberate across a century and around the planet. Linked Hybrid shows that their progeny can be part of a sunnier future that the dystopian ones science fiction movies depend on for dramatic tension and noir atmosphere.

SHoP Architects' American Copper Buildings were completed in 2018. The project's towers are connected by a bridge containing a lap pool and lounge, touted as the highest skybridge in New York City and the first to be built in decades. It is proof of the continuing power of the Gimbels bridge, just the other side of the Empire State Building, to inspire.

What does the future hold for the Gimbels skybridge, the "Chartres" of those early spans that gave so much to the future? It cries out for the landmark designation that would protect it, but this would require also designating of the old Gimbels and Cuyler buildings that hold it up. It's impossible to imagine this being done by our current Landmarks Preservation Commission, which wouldn't even designate McKim, Mead & White's adjacent Hotel Pennsylvania a landmark. The Gimbels store clearly merits consideration for landmark status. It was designed by Daniel Burnham, one of the nation's most influential architects and urban planners.

Christopher Gray's article stated that the buildings connected by the skybridge have been separately owned since 1994 and that plans were filed in 1995 to remove it. He speculated that the daunting cost of demolition may have stayed the bridge's execution: "Perhaps money alone is preserving our 20th-century Chartres." This might be enough to keep it aloft indefinitely were the Empire Station Complex abandoned. If the plan is approved, its zoning changes would greatly increase the built square footage allowed on the Gimbels site. Like most of the property that would be transformed by the Empire Station Complex, the site is owned by Vornado Realty Trust. The more extra area Vornado is allowed to build there, the less reason for it to reuse Gimbels and the more to demolish it and its skybridge, and build all new. In a better world, Vornado would recognize the cultural and potential market value of its property, and incorporate it as the base of any taller building allowed by zoning. Or the Empire Station Complex plan might be modified to make zoning increases contingent on this. That would take the intervention of more enlightened leadership; the project's Draft Environmental Impact Statement states that there are no historic resources on the Gimbels site.

Even if no longer used as a connector, the Gimbels bridge is wide enough for its three levels to follow modern-skybridge examples and contain programmatic space. It could house tenant-attracting board rooms, lounges, or other amenities with dramatic views, accessed from one side. A little imagination and New York know-how could allow other landmark-worthy structures in the Empire Station Complex's path to be saved without defeating the plan's purpose. Foundations could certainly be reconfigured under Saint John the Baptist Church and the Penn Station Powerhouse to allow new tracks and platforms below. Blending authentic New York texture with new development would add great appeal. Steven Spielberg's West Side Story, from its opening to closing credits, is a paean to the established texture of New York. Not surprisingly, the film includes a likeness of the Gimbel's bridge.

Hamburg's Elbphilharmonie is a mixed-use complex in the megastructure tradition, housing concert halls, restaurants, bars, conference rooms, a hotel, a spa, apartments, and parking. Designed by Herzog & de Meuron and completed in 2016, the project reuses a nondescript 1960s brick warehouse as its base. The warehouse reads as an underlying archaeological stratum, expressing how Hamburg's cultural present is built on its geography and history as a working port.

The Gimbels store could similarly serve as a value-adding base for an even larger building. Its famed designer and architectural merit aside, the building tells of the neighborhood's intertwined garment-center and retail-district histories. Gimbels was the major competitor of nearby Macy's, and was completed in the same year as the original Penn Station, near which it was strategically built. Such buildings tell how a neighborhood came to be. They give it historic resonance and a unique identity that can't be made from scratch—the sort of authentic character that makes people want to live in places like New York. Recycling this embodied history would complement the environmental sustainability of adaptive reuse, for which Gimbels cries out. The nearly million-square-foot structure has enormous embedded energy, high structural capacity, tall ceilings, and abundant windows. It could be adaptively reused for any number of purposes.

Imaginative reuse of old buildings has earned growing recognition not just on environmental grounds, but critically. Last year's Pritzker Prize—architecture's highest honor—was awarded to Lacatan & Vassal, the French firm that prides itself on never having demolished a building to construct a new one. This is the direction of the world's enlightened architecture today—the reverse of what the Empire Station Complex proposes. The plan's reversion to Robert Moses-era clearcutting of whole city blocks is a special embarrassment for a city that once led the world into the future.

The Empire Station Complex would follow the formula of the unloved Hudson Yards development, but its destruction of historic architecture will make it even more regrettable. New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman put his finger on Hudson Yards' defining failure, writing that it gives physical form to "a pernicious theory of civic welfare that presumes private development is New York’s primary goal, the truest measure of urban vitality and health, with money the city’s only real currency." Historic architecture that continues to engage the imagination and inspire is another, very real currency. Miami wouldn't be the international brand and destination it is if South Beach's Art Deco hotels had been replaced by larger ones rather than preserved. Who visits or moves to New York for Hudson Yards? It's Teflon to the imagination, just as the Empire Station Complex promises to be—the very opposite of the mythic New York embodied in the Gimbels skybridge.

photo credits:

American Copper Buildings NY1 (cropped).jpg by Acroterion CC BY-SA 4.0 Int'l

Elbpjilharmonie, Hamburg.jpg by Hachercatxxy CC BY-SA 4.0 Int'l.

The Future Still Needs the Gimbels Skybridge

For nearly a century, the Gimbels skybridge has served as a kind of gatehouse announcing Pennsylvania Station on the next block west. Few would guess that its interior was once continuous with the station's. The bridge will disappear if plans for the Empire Station Complex proceed. This would be a terrible loss. It is by far the most prominent aerial bridge from an era when the rest of the world looked to New York as the skyscraping, multi-level City of the Future—the crowning example of a phenomenon that influenced modern architecture and still captivates and inspires.

According to a 2014 New York Times piece by Christopher Gray, the bridge was built in 1926 when the Gimbels department store acquired the Cuyler Building across West 32nd Street and hired Shreve & Lamb—soon to be Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, and architects of the nearby Empire State Building—to connect offices in the building to the main store. Gray wrote, "The architects’ design was a no-holds-barred exemplar of the pedestrian bridge, a triplex skywalk with broad windows and magnificent copper cladding."

Gray observed that, "Although there is classical ornament, such as pilasters and coffers, the flat, machinelike character of the material suggests Art Deco, then barely emergent in the United States." He noted that in 1982 The New Yorker called the bridge "the Chartres of aerial tunnelry."

A 1924 skybridge across 33rd Street, also by Shreve & Lamb, linked the other side of Gimbels to the former Saks store. (It is shown being demolished in 1966.) When Saks moved to its Fifth Avenue location in 1922, Gimbels took over the old building, operating it as Saks-34th Street. The tamely classical Gimbels-Saks bridge shows how far its architects' style stepped into the future by the time of the Gimbels-annex bridge two years later.

The two Gimbels bridges were part of a layered transportation arrangement for which New York was world famous. The streets beneath these bridges passed in turn over the subway, accessible through the Gimbels store. A pedestrian tunnel also connected Gimbels to Pennsylvania Station, passing beneath the Hotel Pennsylvania and Seventh Avenue. One could have entered this enclosed system through Gimbels, its annex, or Saks-34th Street and next stepped outdoors in Chicago, having accessed Penn Station through the connecting bridge-tunnel-building network.

The Hotel Pennsylvania and the Governor Clinton (now Stewart) Hotel were also part of this network, linked to the station by tunnels under Seventh Avenue. An out-of-towner could arrive by train at Penn station, get a haircut in its barber shop, buy underwear in Gimbels' bargain basement and a suit at Saks, wear them to dinner in a station or hotel restaurant, listen to a big band in the Hotel Pennsylvania's Café Rouge, sleep in one of the hotels' thousands of beds, breakfast in the station's cafeteria, and return home—without ever stepping outdoors. The linked buildings provided enough services to amount to a city within a city. Like their contemporary mixed-use complex at Grand Central Terminal, they anticipated the megastructure movement of the 1960s and 70s which melded buildings to transportation and aspired to place the full range of urban functions under one roof. In his 1976 book, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past, Reyner Banham wrote that "patriotic Gothamites eager to claim the concept as a New York invention" could point to Penn Station, Grand Central, and Rockefeller Center. The movement had peaked by the time of his writing but it moved architecture's needle. It's ideas still guide leading architectural theorists like Rem Koolhaas and Steven Holl.

Shreve, Lamb & Harmon's Art Deco Empire State Building is seen beyond their proto-Deco Gimbels skybridge which Christopher Gray called "one of the city's great works of metal." Both were designed in the late 1920s, a mythic period of concentrated activity when the exuberance of New York architecture reached a crescendo and many of the city's best-loved and most defining works were produced. Both structures were the apotheosis of their type, the aerial bridge and skyscraper, which in combination dominated early-twentieth-century visions of cities to come. When Kuala Lumpur's 1998 Petronas Towers followed in the Empire State Building's footsteps as the world's tallest buildings, their linking skybridge carried the DNA of this imagery.

The Empire State Building's top, another of the city's great works of metal, was touted as a mooring mast for zeppelins. Impractical for this use, its real purpose was to contribute to the building's record-setting height. The mooring-mast claim was telling, though. The skies of urban fantasies inspired by New York were alive with airships. It's as if the Empire State Building's designers felt obliged to deliver. Like skybridges and skyscrapers, lighter-than-air vehicles resisted gravity. These ingredients mixed to create popular urban visions that promised liberation from an earthbound existence.

Images like Harry M. Pettit's rendering for Moses King’s guidebook, Views of New York, and William Robinson Leigh's painting, "Visionary City," both from 1908, exaggerated New York's towers and aerial pathways to project the future. Practicality aside, these cityscapes looked thrilling to inhabit. Aerial bridges allow people to magically step through building façades and cross streets in the air. Space takes on dizzying visual depth and unprecedented three-dimensional navigability. All of this plays to our fundamental condition as mobile bodies in space possessed of free will. The immersive motion in these images coincided with the advent of popular movies which also appealed to the modern appetite for speed, daring, and excitement.

The illustration at left was featured on the cover of Scientific American in 1913 and reproduced the same year as "The Circulation of the Future and the Cloudscrapers of New York" in the Milanese magazine L'Illustrazione Italiana. Such images inspired the influential Milan-based Italian Futurist movement, as seen in Antonio Sant'Elia's study for his project La Città Nuova (The New City) at right.

This 1914 rendering is Sant'Elia's most fully developed rendering of La Città Nuova. (He was killed two years later in World War One at just 28.) Bridges, overpasses, and transportation systems aren't tacked onto the static buildings of a traditional city, but used as the building blocks of a new kind of dynamic, city-scale structure that jettisons architectural history.

In the 1914 image at left, Sant'Elia imagined a station for airplanes and trains with funiculars. Manhattan's Westyard Distribution Center at right was designed by Davis Brody and opened in 1969—one of countless buildings around the world influenced by Sant'Elia's unbuilt body of work. The historic photo shows Westyard straddling the West Side Rail Yards. It has been renovated as Five Manhattan West. The block of the railyard beyond it has been decked over and developed as Hudson Yards. The block in the foreground has been decked over and developed as part of Midtown West, with a central pedestrian mall running from Five Manhattan West to Ninth Avenue directly opposite the west entrance of the new Moynihan Train Hall. The mall's axis resumes on the other side of Moynihan Train Hall and Penn Station as 32nd Street, passing directly under the Gimbels skybridge like a through-line of architectural history.

Five Manhattan West, formerly Westyard, is seen with its newly enhanced dynamic diagonals at upper right in this rendering of the High Line's planned Moynihan Connector. The pedestrian bridge will link a tree-covered extension of the High Line's spur to the new Manhattan West mall (a right turn just past the pink-flowering trees) which approaches the Train Hall. Another connector will link the north leg of the High Line to the west terrace of the Javits Center and a long-planned but never-built pedestrian bridge over the West Side Highway to Hudson River Park. Together with the High Line itself, this pedestrian network, raised above street traffic, may be one of the closest things ever built to those layered-city magazine fantasies that inspired Sant'Elia and the Futurists.

Fritz Lang said his classic 1927 film Metropolis was inspired by a 1924 visit to New York. It was also clearly influenced by futuristic visions of New York and Sant'Elia's projects, as have been science fiction movies from Blade Runner to Brazil to The Fifth Element, the latter featuring a future New York dense with skybridges and flying taxis. The richly activated three-dimensionality of early visions on paper is inherently cinematic, as witnessed by countless cinematic shoot-outs on the monkey-bar catwalks and ladders of abandoned warehouses. Forward-looking architecture naturally shares territory in the future with science fiction; Frank Lloyd Wright's 1924 Ennis House was still out-there enough to portray 2019 Los Angeles in Blade Runner.

This rendering of the 1963 Walking City project by the avant-garde architectural group Archigram is captioned: "Each walking unit houses not only a key element of the capital, but also a large population of world-traveler-workers." With its leg-like bridges, the Walking City is in the futuristic skybridge-city tradition. It is also in the city-within-a-city tradition of interconnected buildings forming self-contained complexes like the ones centered on Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal. The scheme does the motion-infused city one better—the city itself moves. Reyner Banham included this image in Megastructure, writing of its units: "Their location here in the East River, with the towers of Manhattan in the background, suggests a deliberate challenge to older visions of the future."

Freed from the land and knee-deep in the Hudson against a backdrop of midtown skyscrapers, Architect Steven Holl's 1990 Parallax Towers project mirrors Archigram's Walking City on the opposite side of Manhattan. Its "hybrid buildings" with diverse functions would be connected both underwater and by skybridges.

Holl's 2009 Linked Hybrid project in Beijing shows that his Parallax Towers scheme was far from a pipe dream. Its eight towers linked by eight bridges house 2,500 residents and recall Matisse's ring of dancers clasping hands—an apt metaphor for Holl's intent to un-silo residents, generate random relationships, and "express a collective aspiration." (They also recall Gimbels when it had a bridge on each side like outstretched arms.) The skybridges contain a swimming pool, fitness room, café, and gallery. Holl's description places the complex in the best cinematic, layered-city, proto-megastructure New York tradition:

As a "city within a city" the new place has a filmic urban experience of space; around, over and through multifaceted spatial layers. A three-dimensional public urban space, the project has programs that vary from commercial, residential, and educational to recreational.

In this dazzling project, New York's early skybridges reverberate across a century and around the planet. Linked Hybrid shows that their progeny can be part of a sunnier future that the dystopian ones science fiction movies depend on for dramatic tension and noir atmosphere.

SHoP Architects' American Copper Buildings were completed in 2018. The project's towers are connected by a bridge containing a lap pool and lounge, touted as the highest skybridge in New York City and the first to be built in decades. It is proof of the continuing power of the Gimbels bridge, just the other side of the Empire State Building, to inspire.

What does the future hold for the Gimbels skybridge, the "Chartres" of those early spans that gave so much to the future? It cries out for the landmark designation that would protect it, but this would require also designating of the old Gimbels and Cuyler buildings that hold it up. It's impossible to imagine this being done by our current Landmarks Preservation Commission, which wouldn't even designate McKim, Mead & White's adjacent Hotel Pennsylvania a landmark. The Gimbels store clearly merits consideration for landmark status. It was designed by Daniel Burnham, one of the nation's most influential architects and urban planners.

Christopher Gray's article stated that the buildings connected by the skybridge have been separately owned since 1994 and that plans were filed in 1995 to remove it. He speculated that the daunting cost of demolition may have stayed the bridge's execution: "Perhaps money alone is preserving our 20th-century Chartres." This might be enough to keep it aloft indefinitely were the Empire Station Complex abandoned. If the plan is approved, its zoning changes would greatly increase the built square footage allowed on the Gimbels site. Like most of the property that would be transformed by the Empire Station Complex, the site is owned by Vornado Realty Trust. The more extra area Vornado is allowed to build there, the less reason for it to reuse Gimbels and the more to demolish it and its skybridge, and build all new. In a better world, Vornado would recognize the cultural and potential market value of its property, and incorporate it as the base of any taller building allowed by zoning. Or the Empire Station Complex plan might be modified to make zoning increases contingent on this. That would take the intervention of more enlightened leadership; the project's Draft Environmental Impact Statement states that there are no historic resources on the Gimbels site.

Even if no longer used as a connector, the Gimbels bridge is wide enough for its three levels to follow modern-skybridge examples and contain programmatic space. It could house tenant-attracting board rooms, lounges, or other amenities with dramatic views, accessed from one side. A little imagination and New York know-how could allow other landmark-worthy structures in the Empire Station Complex's path to be saved without defeating the plan's purpose. Foundations could certainly be reconfigured under Saint John the Baptist Church and the Penn Station Powerhouse to allow new tracks and platforms below. Blending authentic New York texture with new development would add great appeal. Steven Spielberg's West Side Story, from its opening to closing credits, is a paean to the established texture of New York. Not surprisingly, the film includes a likeness of the Gimbel's bridge.

Hamburg's Elbphilharmonie is a mixed-use complex in the megastructure tradition, housing concert halls, restaurants, bars, conference rooms, a hotel, a spa, apartments, and parking. Designed by Herzog & de Meuron and completed in 2016, the project reuses a nondescript 1960s brick warehouse as its base. The warehouse reads as an underlying archaeological stratum, expressing how Hamburg's cultural present is built on its geography and history as a working port.

The Gimbels store could similarly serve as a value-adding base for an even larger building. Its famed designer and architectural merit aside, the building tells of the neighborhood's intertwined garment-center and retail-district histories. Gimbels was the major competitor of nearby Macy's, and was completed in the same year as the original Penn Station, near which it was strategically built. Such buildings tell how a neighborhood came to be. They give it historic resonance and a unique identity that can't be made from scratch—the sort of authentic character that makes people want to live in places like New York. Recycling this embodied history would complement the environmental sustainability of adaptive reuse, for which Gimbels cries out. The nearly million-square-foot structure has enormous embedded energy, high structural capacity, tall ceilings, and abundant windows. It could be adaptively reused for any number of purposes.

Imaginative reuse of old buildings has earned growing recognition not just on environmental grounds, but critically. Last year's Pritzker Prize—architecture's highest honor—was awarded to Lacatan & Vassal, the French firm that prides itself on never having demolished a building to construct a new one. This is the direction of the world's enlightened architecture today—the reverse of what the Empire Station Complex proposes. The plan's reversion to Robert Moses-era clearcutting of whole city blocks is a special embarrassment for a city that once led the world into the future.

The Empire Station Complex would follow the formula of the unloved Hudson Yards development, but its destruction of historic architecture will make it even more regrettable. New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman put his finger on Hudson Yards' defining failure, writing that it gives physical form to "a pernicious theory of civic welfare that presumes private development is New York’s primary goal, the truest measure of urban vitality and health, with money the city’s only real currency." Historic architecture that continues to engage the imagination and inspire is another, very real currency. Miami wouldn't be the international brand and destination it is if South Beach's Art Deco hotels had been replaced by larger ones rather than preserved. Who visits or moves to New York for Hudson Yards? It's Teflon to the imagination, just as the Empire Station Complex promises to be—the very opposite of the mythic New York embodied in the Gimbels skybridge.

photo credits:

American Copper Buildings NY1 (cropped).jpg by Acroterion CC BY-SA 4.0 Int'l

Elbpjilharmonie, Hamburg.jpg by Hachercatxxy CC BY-SA 4.0 Int'l.

Mythical Lower Manhattan, Part 2

The 2002 World Trade Center competition entry by the team of architects Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey and Steven Holl is shown in its finished form at left, and in an earlier study by Holl, at right. The images are juxtaposed as they appear in Holl’s book, Urbanisms. The finished scheme has the regimentation of Upper Manhattan’s street grid while the study suggests Lower Manhattan’s off-kilter intersections. (One legend has it that the slang meaning of “square” comes from Greenwich Village’s bohemian heyday, when free thinkers lived on its unaligned streets and conformists on uptown’s rectangular blocks.) Holl asserts that the distinction mattered to him, in his book Architecture Spoken:

I had been working on a vision called Parallax Towers years before, in which I envisioned horizontal linkage of vertical thin towers. The notion of these as hybrid buildings, meaning they had offices, living, commercial aspects and they were linked in section, orchestrating what is normally known as a vertical typology into a horizontal one. The flexibility of that idea would work for the program we were given for this new project. Peter Eisenman and I fought until the end on how the horizontals should meet the verticals. I always wanted them to move, as in my original project from the early nineties, but he wanted them straight. The compromise was to keep them straight.

Despite this lost battle, Holl would speak proudly of the end result in a lecture at SCI-Arc on September 11, 2003, and bitterly reject architecture critic Paul Goldberger's description of its "icy rationality." Nonetheless, his earlier resistance to the squared-off default, in what he calls "endless and enormously confrontational meetings,” is telling.

Like his World Trade Center proposal, Steven Holl’s Parallax Towers, envisioned to rise from the Hudson off the Upper West Side of Manhattan, are distinguished by sloped bridges. In describing their varied pitches as movement, Holl underscores the way they express human volition and motility. The unsolicited project is one of several created by Holl before his time was commandeered by real commissions. When these visions were collected in an exhibition called Edge of a City, the architect Stan Allen wrote:

They belong to a tradition of utopian realism like that of Superstudio and Yona Friedman in the sixties and the Japanese Metabolists in the fifties; they recall Raymond Hood's Residential Bridges and Le Corbusier's urban proposals of the twenties and thirties. As with other architects working in this tradition, there is something seemingly arrogant in Holl’s assuming the power to remake the image of the city. Yet this is the territory in which these projects operate most effectively: not as concrete proposals, but as infiltrations of the collective imagination, producing an idea of what the city could be.

Allen’s reference to popular suggestion and the collective imagination relates this territory to myth, and its expression of shared human fears and desires.

An image from Superstudio’s 1969 Continuous Monument is shown above Steven Holl’s 1977 Gymnasium Bridge project. They share a visionary tradition and have formal similarities. Both projects substitute a multi-purpose blocky framework for individual buildings. In Superstudio’s hands, this form taps fears of oppressive “scientific methods for perpetuating standard models worldwide,” while Holl makes it a utopian bridge to social re-engagement in a mixed-use - "hybrid" is his constant word – building that hints at the idea of a floating horizontal skyscraper and weightless architecture. For decades, Holl would build on the Gymnasium Bridge in other visions and, notably, major commissions for real buildings.

The building section of Steven Holl's 1992-2002 Simmons Hall at MIT is shown below a 1990 Berlin Free Zone image by his friend Lebbeus Woods. Rebellion against cubic space is seen in both. Holl is about creating the experience of spatial porosity found in cities like Naples; Woods is about myth-like narratives - and political provocations - of transformation. Neither aim is catnip to businesslike clients. Holl is known for turning away commissions that would deny his vision; Woods was a full-fledged rebel angel, refusing to serve clients at all, the better to create uncompromised new worlds.

The body's interaction with the physical world, its movement through space and time, and its experience of changing perspectives are architecture's starting point for Steven Holl, reflecting his interest in the phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty. In this photo of his Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, static Cartesian space and the vanishing points of its diminishing perspective grid are assiduously avoided; subjective experience is prioritized, and the body's fundamental nature as a sensate, moving entity is engaged and celebrated. The man who designed this space must indeed have regretted seeing his World Trade Center vision regress into the square world’s frozen grid, for its experiential lockstep if not its association with domineering, externally applied reason.

In what might be a belly-of-the-beast view inside Superstudio's Continuous Monument, New York's 1960 Union Carbide Building lends grim new meaning to "vanishing point." Its static cage of X, Y and Z-axes captures a work atmosphere on the verge of precipitating into a half-century hail of Cartesian cubicles. Union Carbide was designed by SOM, the firm responsible for the One World Trade Center tower we will have. SOM's own more poetic, torqued and asymmetrical early versions of the tower ultimately succumbed to the old default of geometric simplicity, a lifeless twist on the original Twin Tower boxes that Lewis Mumford called "just glass-and-metal filing cabinets." The genius of Mumford's characterization is its underlying indictment of such architecture's failure to inspire, its complicity in the modern world's debasement of human lives. The Union Carbide interior photo could illustrate Joseph Campbell's words in The Power of Myth:

When you think about what people are actually undergoing in our civilization, you realize it’s a very grim thing to be a modern human being. The drudgery of the lives of most of the people who have to support families – well, it’s a life-extinguishing affair.... an imposed system is the threat to our lives that we all face today. Is the system going to flatten you out and deny you your humanity, or are you going to make use of the system to the attainment of human purposes? How do you relate to the system so that you are not compulsively serving it?... The thing to do is learn to live in your period of history as a human being.... By holding to your own ideals for yourself and ... rejecting the system's impersonal claims upon you.

Flattening - and flat-surfaced - architecture reflects both the tyranny of powers which have the wherewithal to build, and that of the intellect over emotion and nature. This architecture is so pervasive and accepted as to be invisible, leaving its source and merits rarely examined. David Pye is an exception, in his book The Nature and Aesthetics of Design:

A flat surface will touch any other flat surface at all points.... Thus a mason building a wall need not fit each stone he lays to the stone below it. Having cut all his stones to flat surfaces first, he knows that any stone will bed steadily on any other without having to be fitted to it individually.

The versatility of flat surfaces is not commonly seen in nature. Stones which cleave under frost exhibit it; but the breadth of its application was a discovery of man’s, and one of his most valuable, for it enabled him to reduce the cost of construction in all materials very considerably. An extension of the discovery was that if the components of a structure were ‘squared’, i.e. were given two flat surfaces at right angles, then they would not only touch each other at all points of the adjacent surfaces, but would also do the same to a third component.

We take all this very much for granted. Any house and its contents, and the toy bricks on the nursery floor, showed us this before we could talk. The extraordinary rigmarole which I have had to use in writing about it is perhaps evidence that we take it as part of the natural order of things, which it is not....

Only those parts of a component which touch others need be squared. The sides and under surface of a beam need not be squared for the sake of economy, yet from the earliest times we see that this was done, exhibiting the tendency to standardization which appears in all constructional design.... Standardized pieces of material provide the designer with convenient limitations on shape from the start of his job, of the sort which are always welcome, and perhaps necessary, to the designer.

As Pye notes, we take this unnatural flatness for granted from infancy, impose more of it on ourselves than necessary, and have even become dependent on it. That it has infected our brains is proven by the cortical push-back we feel while walking between the tilted walls of Richard Serra's sculptures, and in the Muller-Lyer optical illusion, which tricks only eyes brought up in orthogonal space. All this matters to the extent that squaring disguises limits placed on us both by others and ourselves. Lebbeus Woods wrote in his book Radical Reconstructions:

Architects usually design rectilinear volumes of space following Cartesian rules of geometry, and such spaces are no better suited to being used for office work than as a bedroom or a butcher shop.... While architects speak of designing space that satisfies human needs, human needs are actually being shaped to satisfy designed space, and the abstract systems of thought and organization on which design is based.... Design can be a means of controlling human behavior, and of maintaining this control into the future.

If this sounds Orwellian, think of the mason's pre-squared stone, which saves him hunting for one that fits naturally but compels him to build straight walls, and compare what Orwell said about clichés in his essay Politics and the English Language:

If you use readymade phrases, you not only don’t have to hunt about for words; you also don’t have to bother with the rhythms of your sentences, since these phrases are generally so arranged as to be more or less euphonious.... They will construct your sentences for you – even think your thought for you, to a certain extent – and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself. It is at this point that the special connection between politics and the debasement of language becomes clear.... Orthodoxy, of whatever color, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style.

The worst aspect of this control may be that it comes from what Woods calls "abstract systems of thought." Ever since Superstudio contrasted the orthogonal orthodoxy of its white, gridded, rectilinear Continuous Monument with soft green nature, Cartesian architecture has stood for our bloodless intellect - Goldberger's "icy rationality" - in mortal combat with our true nature. In The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell illustrates this dialectic with an example from Wagner's Ring:

When Siegfried has killed the dragon and tasted the blood, he hears the song of nature. He has transcended his humanity and reassociated himself with the powers of nature, which are the powers of our life, and from which our minds remove us.

You see, consciousness thinks it’s running the shop. But it’s a secondary organ of the total human being, and it must not put itself in control. It must submit and serve the humanity of the body....

If Campbell's reference to what "the body's interested in" merges nicely with Steven Holl's focus on bodily engagement with architecture, his use of myth and emphasis on self-determination all but define Lebbeus Woods, author of such titles as Anarchitecture and Radical Reconstructions. In the latter, Woods wrote: "The mythless man stands eternally hungry, surrounded by past ages, and digs and grubs for roots."

Woods' image Lower Manhattan has the psychological resonance of myth. Water of course represents the unconscious. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell describes the well in Grimm’s Tale, “The Frog King,” as "that unconscious deep ('so deep that the bottom cannot be seen') wherein are hoarded all of the rejected, unadmitted, unrecognized, unknown, or undeveloped factors, laws, and elements of existence." As if to convey this, Woods replaced the drained harbor’s smooth bed with plummeting cliff faces rendered in jagged lines, the non-linear complement to the establishment laws that rule above the surface. The unconscious is further invoked by Woods' description of "peeling back the surface to see what the planetary reality is." As Joseph Campbell noted, humans are the consciousness of the earth. For all its skyscraping, the Lower Manhattan of Woods' vision is just a veneer of civilization, "relatively small human scratchings on the surface" of a deeper realm that dwarfs it and puts it in perspective. Woods seemed to suggest the possibility of living in accord with this deeper reality, saying: "The underground – or lower Manhattan – is revealed, and, in the drawing, there are suggestions of inhabitation in that lower region." His own analysis is otherwise limited to observations on scale and density. In text accompanying the image's publication in a 1999 issue of Arbitare he wrote:

Manhattan is not Big, but Too Small, which accounts for its congestion, its unique cultural intensity. Lille and Shanghai cannot becomes cultures of congestion, no matter how big they are or become. At issue is the matter of scale, not of size. Scale is something more subtle than size, having to do with precise relationships.

In exaggerating Manhattan's containment, Woods’ image both emphasizes its intensity and makes it read as a single structure housing all the activities of the city. It may be his response to the statement by Le Corbusier to the American press, which Woods quotes, that "your skyscrapers are too small." But by then, Corb was already infiltrating the collective imagination with visions of multi-use mega-blocks, which would come to bastardized and damning fruition in New York's housing projects.

To be continued . . .

Mythical Lower Manhattan, Part 2

The 2002 World Trade Center competition entry by the team of architects Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey and Steven Holl is shown in its finished form at left, and in an earlier study by Holl, at right. The images are juxtaposed as they appear in Holl’s book, Urbanisms. The finished scheme has the regimentation of Upper Manhattan’s street grid while the study suggests Lower Manhattan’s off-kilter intersections. (One legend has it that the slang meaning of “square” comes from Greenwich Village’s bohemian heyday, when free thinkers lived on its unaligned streets and conformists on uptown’s rectangular blocks.) Holl asserts that the distinction mattered to him, in his book Architecture Spoken:

I had been working on a vision called Parallax Towers years before, in which I envisioned horizontal linkage of vertical thin towers. The notion of these as hybrid buildings, meaning they had offices, living, commercial aspects and they were linked in section, orchestrating what is normally known as a vertical typology into a horizontal one. The flexibility of that idea would work for the program we were given for this new project. Peter Eisenman and I fought until the end on how the horizontals should meet the verticals. I always wanted them to move, as in my original project from the early nineties, but he wanted them straight. The compromise was to keep them straight.

Despite this lost battle, Holl would speak proudly of the end result in a lecture at SCI-Arc on September 11, 2003, and bitterly reject architecture critic Paul Goldberger's description of its "icy rationality." Nonetheless, his earlier resistance to the squared-off default, in what he calls "endless and enormously confrontational meetings,” is telling.

Like his World Trade Center proposal, Steven Holl’s Parallax Towers, envisioned to rise from the Hudson off the Upper West Side of Manhattan, are distinguished by sloped bridges. In describing their varied pitches as movement, Holl underscores the way they express human volition and motility. The unsolicited project is one of several created by Holl before his time was commandeered by real commissions. When these visions were collected in an exhibition called Edge of a City, the architect Stan Allen wrote:

They belong to a tradition of utopian realism like that of Superstudio and Yona Friedman in the sixties and the Japanese Metabolists in the fifties; they recall Raymond Hood's Residential Bridges and Le Corbusier's urban proposals of the twenties and thirties. As with other architects working in this tradition, there is something seemingly arrogant in Holl’s assuming the power to remake the image of the city. Yet this is the territory in which these projects operate most effectively: not as concrete proposals, but as infiltrations of the collective imagination, producing an idea of what the city could be.

Allen’s reference to popular suggestion and the collective imagination relates this territory to myth, and its expression of shared human fears and desires.

An image from Superstudio’s 1969 Continuous Monument is shown above Steven Holl’s 1977 Gymnasium Bridge project. They share a visionary tradition and have formal similarities. Both projects substitute a multi-purpose blocky framework for individual buildings. In Superstudio’s hands, this form taps fears of oppressive “scientific methods for perpetuating standard models worldwide,” while Holl makes it a utopian bridge to social re-engagement in a mixed-use - "hybrid" is his constant word – building that hints at the idea of a floating horizontal skyscraper and weightless architecture. For decades, Holl would build on the Gymnasium Bridge in other visions and, notably, major commissions for real buildings.

The building section of Steven Holl's 1992-2002 Simmons Hall at MIT is shown below a 1990 Berlin Free Zone image by his friend Lebbeus Woods. Rebellion against cubic space is seen in both. Holl is about creating the experience of spatial porosity found in cities like Naples; Woods is about myth-like narratives - and political provocations - of transformation. Neither aim is catnip to businesslike clients. Holl is known for turning away commissions that would deny his vision; Woods was a full-fledged rebel angel, refusing to serve clients at all, the better to create uncompromised new worlds.

The body's interaction with the physical world, its movement through space and time, and its experience of changing perspectives are architecture's starting point for Steven Holl, reflecting his interest in the phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty. In this photo of his Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, static Cartesian space and the vanishing points of its diminishing perspective grid are assiduously avoided; subjective experience is prioritized, and the body's fundamental nature as a sensate, moving entity is engaged and celebrated. The man who designed this space must indeed have regretted seeing his World Trade Center vision regress into the square world’s frozen grid, for its experiential lockstep if not its association with domineering, externally applied reason.

In what might be a belly-of-the-beast view inside Superstudio's Continuous Monument, New York's 1960 Union Carbide Building lends grim new meaning to "vanishing point." Its static cage of X, Y and Z-axes captures a work atmosphere on the verge of precipitating into a half-century hail of Cartesian cubicles. Union Carbide was designed by SOM, the firm responsible for the One World Trade Center tower we will have. SOM's own more poetic, torqued and asymmetrical early versions of the tower ultimately succumbed to the old default of geometric simplicity, a lifeless twist on the original Twin Tower boxes that Lewis Mumford called "just glass-and-metal filing cabinets." The genius of Mumford's characterization is its underlying indictment of such architecture's failure to inspire, its complicity in the modern world's debasement of human lives. The Union Carbide interior photo could illustrate Joseph Campbell's words in The Power of Myth:

When you think about what people are actually undergoing in our civilization, you realize it’s a very grim thing to be a modern human being. The drudgery of the lives of most of the people who have to support families – well, it’s a life-extinguishing affair.... an imposed system is the threat to our lives that we all face today. Is the system going to flatten you out and deny you your humanity, or are you going to make use of the system to the attainment of human purposes? How do you relate to the system so that you are not compulsively serving it?... The thing to do is learn to live in your period of history as a human being.... By holding to your own ideals for yourself and ... rejecting the system's impersonal claims upon you.

Flattening - and flat-surfaced - architecture reflects both the tyranny of powers which have the wherewithal to build, and that of the intellect over emotion and nature. This architecture is so pervasive and accepted as to be invisible, leaving its source and merits rarely examined. David Pye is an exception, in his book The Nature and Aesthetics of Design:

A flat surface will touch any other flat surface at all points.... Thus a mason building a wall need not fit each stone he lays to the stone below it. Having cut all his stones to flat surfaces first, he knows that any stone will bed steadily on any other without having to be fitted to it individually.

The versatility of flat surfaces is not commonly seen in nature. Stones which cleave under frost exhibit it; but the breadth of its application was a discovery of man’s, and one of his most valuable, for it enabled him to reduce the cost of construction in all materials very considerably. An extension of the discovery was that if the components of a structure were ‘squared’, i.e. were given two flat surfaces at right angles, then they would not only touch each other at all points of the adjacent surfaces, but would also do the same to a third component.

We take all this very much for granted. Any house and its contents, and the toy bricks on the nursery floor, showed us this before we could talk. The extraordinary rigmarole which I have had to use in writing about it is perhaps evidence that we take it as part of the natural order of things, which it is not....

Only those parts of a component which touch others need be squared. The sides and under surface of a beam need not be squared for the sake of economy, yet from the earliest times we see that this was done, exhibiting the tendency to standardization which appears in all constructional design.... Standardized pieces of material provide the designer with convenient limitations on shape from the start of his job, of the sort which are always welcome, and perhaps necessary, to the designer.

As Pye notes, we take this unnatural flatness for granted from infancy, impose more of it on ourselves than necessary, and have even become dependent on it. That it has infected our brains is proven by the cortical push-back we feel while walking between the tilted walls of Richard Serra's sculptures, and in the Muller-Lyer optical illusion, which tricks only eyes brought up in orthogonal space. All this matters to the extent that squaring disguises limits placed on us both by others and ourselves. Lebbeus Woods wrote in his book Radical Reconstructions:

Architects usually design rectilinear volumes of space following Cartesian rules of geometry, and such spaces are no better suited to being used for office work than as a bedroom or a butcher shop.... While architects speak of designing space that satisfies human needs, human needs are actually being shaped to satisfy designed space, and the abstract systems of thought and organization on which design is based.... Design can be a means of controlling human behavior, and of maintaining this control into the future.

If this sounds Orwellian, think of the mason's pre-squared stone, which saves him hunting for one that fits naturally but compels him to build straight walls, and compare what Orwell said about clichés in his essay Politics and the English Language:

If you use readymade phrases, you not only don’t have to hunt about for words; you also don’t have to bother with the rhythms of your sentences, since these phrases are generally so arranged as to be more or less euphonious.... They will construct your sentences for you – even think your thought for you, to a certain extent – and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself. It is at this point that the special connection between politics and the debasement of language becomes clear.... Orthodoxy, of whatever color, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style.

The worst aspect of this control may be that it comes from what Woods calls "abstract systems of thought." Ever since Superstudio contrasted the orthogonal orthodoxy of its white, gridded, rectilinear Continuous Monument with soft green nature, Cartesian architecture has stood for our bloodless intellect - Goldberger's "icy rationality" - in mortal combat with our true nature. In The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell illustrates this dialectic with an example from Wagner's Ring:

When Siegfried has killed the dragon and tasted the blood, he hears the song of nature. He has transcended his humanity and reassociated himself with the powers of nature, which are the powers of our life, and from which our minds remove us.

You see, consciousness thinks it’s running the shop. But it’s a secondary organ of the total human being, and it must not put itself in control. It must submit and serve the humanity of the body....

If Campbell's reference to what "the body's interested in" merges nicely with Steven Holl's focus on bodily engagement with architecture, his use of myth and emphasis on self-determination all but define Lebbeus Woods, author of such titles as Anarchitecture and Radical Reconstructions. In the latter, Woods wrote: "The mythless man stands eternally hungry, surrounded by past ages, and digs and grubs for roots."

Woods' image Lower Manhattan has the psychological resonance of myth. Water of course represents the unconscious. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell describes the well in Grimm’s Tale, “The Frog King,” as "that unconscious deep ('so deep that the bottom cannot be seen') wherein are hoarded all of the rejected, unadmitted, unrecognized, unknown, or undeveloped factors, laws, and elements of existence." As if to convey this, Woods replaced the drained harbor’s smooth bed with plummeting cliff faces rendered in jagged lines, the non-linear complement to the establishment laws that rule above the surface. The unconscious is further invoked by Woods' description of "peeling back the surface to see what the planetary reality is." As Joseph Campbell noted, humans are the consciousness of the earth. For all its skyscraping, the Lower Manhattan of Woods' vision is just a veneer of civilization, "relatively small human scratchings on the surface" of a deeper realm that dwarfs it and puts it in perspective. Woods seemed to suggest the possibility of living in accord with this deeper reality, saying: "The underground – or lower Manhattan – is revealed, and, in the drawing, there are suggestions of inhabitation in that lower region." His own analysis is otherwise limited to observations on scale and density. In text accompanying the image's publication in a 1999 issue of Arbitare he wrote:

Manhattan is not Big, but Too Small, which accounts for its congestion, its unique cultural intensity. Lille and Shanghai cannot becomes cultures of congestion, no matter how big they are or become. At issue is the matter of scale, not of size. Scale is something more subtle than size, having to do with precise relationships.

In exaggerating Manhattan's containment, Woods’ image both emphasizes its intensity and makes it read as a single structure housing all the activities of the city. It may be his response to the statement by Le Corbusier to the American press, which Woods quotes, that "your skyscrapers are too small." But by then, Corb was already infiltrating the collective imagination with visions of multi-use mega-blocks, which would come to bastardized and damning fruition in New York's housing projects.

To be continued . . .

Mythical Lower Manhattan, Part 1 - In Memory of Lebbeus Woods

The Dutch architectural photographer Iwan Baan took this helicopter photo of Downtown blacked-out by Hurricane Sandy. A memorable New York Magazine cover, it resonates with a century-old genre; views of a transformed Lower Manhattan from above New York Harbor.

Lebbeus Woods died on October 30th, as Sandy left his downtown neighborhood in the darkness captured by Baan's photo. His 1999 drawing, Lower Manhattan, shows the Hudson and East Rivers dammed, draining the harbor. “The underground – or lower Manhattan – is revealed,” Woods told BLDGBLOG's Geoff Manaugh in an interview, continuing:

So I was speculating on the future of the city and I said, well, obviously, compared to present and future cities, New York is not going to be able to compete in terms of size anymore. It used to be a large city, but now it's a small city compared with Sao Paulo, Mexico City, Kuala Lampur or almost any Asian city of any size. So I said maybe New York can establish a new kind of scale – and the scale I was interested in was the scale of the city to the Earth, to the planet. . . . I wanted to suggest that Lower Manhattan – not lower downtown, but lower in the sense of below the city – could form a new relationship with the planet.

So it was a romantic idea – and the drawing is very conceptual in that sense.

But the exposure of the rock base, or the underground condition of the city, completely changes the scale relationship between the city and its environment. It's peeling back the surface to see what the planetary reality is. And the new scale relationship is not about huge blockbuster buildings; it's not about towers and skyscrapers. It's about the relationship of the relatively small human scratchings on the surface of the earth compared to the earth itself.

Woods' follows long traditions in both his speculation on the future of Lower Manhattan and his use of it as a scale reference. His image is prescient in omitting the World Trade Center towers. They are probably left out, along with the Manhattan Bridge, in the interest of romantic effect. Woods says he worked from aerial photographs. Some of these may have predated the World Trade Center and other blocky buildings he also left out. He'd have had plenty to choose from, given the historic popularity of the subject and viewpoint.

Illustrator Louis Biederman's New York City as it will be in 1999 was widely circulated via the Sunday Edition of Joseph Pulitzer's New York World on December 30th, 1900. A where-will-it-all-end reverie on Lower Manhattan's proliferation of skyscrapers and bridges, the image inaugurates a convention of setting a future scene with fantastic airships. They contribute to a pulsating vision of layered transportation systems that would inform later images like King's Dream of New York and reach cinematic apotheosis in the buzzing dystopian city of Fritz Lang's Metropolis.

Harry Grant Dart's Some Day, in detail above, followed Biederman's lead. Dart's image indulged his particular penchant for fantasy airships. It appeared in the March 4, 1909, Real Estate Number of Life Magazine, alongside A.B. Walker's influential cartoon of a skyscraper frame planted with suburban houses. (Walker's cartoon would be revisited by Rem Koolhaas's 1978 seminal book Delirious New York and SITE's 1981 Highrise of Homes experimental proposal.) The 44-page Life issue includes four more futuristic views of New York, alongside eight ads for cars and six for car-related products, which paint a more accurate picture of the future.

Aerial photos of Lower Manhattan like this one of around 1930 are a staple of the era's postcards. This example is one of many that oblige earlier expectations by delivering a foreground airship, in this case the USS Akron. It captures the locale fulfilling its role as the future's cutting edge, farther ahead of the world than it would ever be again, and just about to be frozen as such by decades of depression, war and recovery.

Architect Raymond Hood began proposing East and Hudson River bridges with 50 to 60 story residential skyscrapers as support pylons in 1925. In 1930 he presented this photomontage of Manhattan densely ringed with residential bridges and interspersed with mountain-like clusters of skyscrapers at selected street intersections. It recalls Louis Biederman's cartoon, New York City as it will be in 1999, both in what it envisions and its title. Hood looked forward only twenty years, calling his project Manhattan 1950. His melding of residential building and bridge is an early step in the direction of 1960s megastructures, monumental frameworks accommodating structure, transportation and all the functions of a city. The megastructure movement reflected architects' conviction at the time of their responsibility to design the whole human environment, a scary prospect indeed.

Reyner Banham astutely identified the appeal of Lower Manhattan as a canvas for new visions of the future. His 1976 book Megastructure is illustrated with this image of Archigram's 1963 Walking City project, showing the conceptual architectural group's walking cities against a backdrop of Wall Street skyscrapers. Banham's caption reads: “Their location here in the East River, with the towers of Manhattan in the background, suggests a deliberate challenge to older visions of the future . . .” By the sixties, Lower Manhattan had become the standard against which to measure urban visions, sealing its own mythic status.

Lower Manhattan's use as a measuring stick for new urban visions followed upon its use as a scale reference. The outline of Albert Kahn Associates' vast Dodge Chicago Aircraft Engine Plant, built for the war effort, was superimposed on Lower Manhattan in the December 1943 issue of The Architectural Forum. While a New Yorker could compare the length of this factory to a walk from the the Battery to the Bowery, the rest of the world could by now relate as well to what had become an iconic cityscape and universal point of reference. The manner in which the plant's outline passes out of sight behind buildings as it weaves among them surpasses the purpose at hand and speaks of this terrain's power to fire the imagination. The image foreshadows visions of city-containing buildings, sometimes rendered as visitors to New York.

Superstudio's theoretical Continuous Monument of 1969 picks up where The Architectural Forum's Dodge Plant image left off, encircling the very same skyscraper blocks. The Dodge Plant outline is not an unlikely influence, given its publication in a major architectural journal and its remarkable similarities. In the words of Superstudio's Toraldo di Francia, The Continuous Monument was "a form of architecture" reflecting a "world rendered uniform by technology, culture and all the other inevitable forms of imperialism." Fellow member Adolfo Natalini said, ". . . in 1969, we started designing negative utopias like The Continuous Monument - images warning of the horrors architecture had in store with its scientific methods for perpetuating standard models worldwide. Of course, we were also having fun." The ultimate sixties megastructure, The Continuous Monument would circle the planet, carrying to its logical conclusion the International Style's vocabulary of rational, gridded rectangular extrusions, and its arrogation of universal applicability to a world homogenized by progress. Manhattan's transfixed skyscrapers are a foil for this new future, contrasting old-school object buildings and individuality with a uniform structure beyond architecture. As in Lebbeus Woods' Lower Manhattan image, the World Trade Center towers are omitted, although The Continuous Monument co-opts and critiques their scaleless box-tube vocabulary.

The most abstracted scheme for the 2002 World Trade Center competition came from the team of architects Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey, and Steven Holl. Their entry's two structures have five scaleless bridge-connected towers, all made of continuous, extruded, white, rectangular sections, and dwarfing conventional skyscrapers. It resembles nothing imagined before so much as Superstudio's Continuous Monument, as if pieces of it had been salvaged and turned on end. Did this Ground Zero team appropriate from Superstudio's project? ArchiTakes will be back to dig deeper.

Mythical Lower Manhattan, Part 1 - In Memory of Lebbeus Woods

The Dutch architectural photographer Iwan Baan took this helicopter photo of Downtown blacked-out by Hurricane Sandy. A memorable New York Magazine cover, it resonates with a century-old genre; views of a transformed Lower Manhattan from above New York Harbor.

Lebbeus Woods died on October 30th, as Sandy left his downtown neighborhood in the darkness captured by Baan's photo. His 1999 drawing, Lower Manhattan, shows the Hudson and East Rivers dammed, draining the harbor. “The underground – or lower Manhattan – is revealed,” Woods told BLDGBLOG's Geoff Manaugh in an interview, continuing:

So I was speculating on the future of the city and I said, well, obviously, compared to present and future cities, New York is not going to be able to compete in terms of size anymore. It used to be a large city, but now it's a small city compared with Sao Paulo, Mexico City, Kuala Lampur or almost any Asian city of any size. So I said maybe New York can establish a new kind of scale – and the scale I was interested in was the scale of the city to the Earth, to the planet. . . . I wanted to suggest that Lower Manhattan – not lower downtown, but lower in the sense of below the city – could form a new relationship with the planet.

So it was a romantic idea – and the drawing is very conceptual in that sense.

But the exposure of the rock base, or the underground condition of the city, completely changes the scale relationship between the city and its environment. It's peeling back the surface to see what the planetary reality is. And the new scale relationship is not about huge blockbuster buildings; it's not about towers and skyscrapers. It's about the relationship of the relatively small human scratchings on the surface of the earth compared to the earth itself.

Woods' follows long traditions in both his speculation on the future of Lower Manhattan and his use of it as a scale reference. His image is prescient in omitting the World Trade Center towers. They are probably left out, along with the Manhattan Bridge, in the interest of romantic effect. Woods says he worked from aerial photographs. Some of these may have predated the World Trade Center and other blocky buildings he also left out. He'd have had plenty to choose from, given the historic popularity of the subject and viewpoint.

Illustrator Louis Biederman's New York City as it will be in 1999 was widely circulated via the Sunday Edition of Joseph Pulitzer's New York World on December 30th, 1900. A where-will-it-all-end reverie on Lower Manhattan's proliferation of skyscrapers and bridges, the image inaugurates a convention of setting a future scene with fantastic airships. They contribute to a pulsating vision of layered transportation systems that would inform later images like King's Dream of New York and reach cinematic apotheosis in the buzzing dystopian city of Fritz Lang's Metropolis.

Harry Grant Dart's Some Day, in detail above, followed Biederman's lead. Dart's image indulged his particular penchant for fantasy airships. It appeared in the March 4, 1909, Real Estate Number of Life Magazine, alongside A.B. Walker's influential cartoon of a skyscraper frame planted with suburban houses. (Walker's cartoon would be revisited by Rem Koolhaas's 1978 seminal book Delirious New York and SITE's 1981 Highrise of Homes experimental proposal.) The 44-page Life issue includes four more futuristic views of New York, alongside eight ads for cars and six for car-related products, which paint a more accurate picture of the future.

Aerial photos of Lower Manhattan like this one of around 1930 are a staple of the era's postcards. This example is one of many that oblige earlier expectations by delivering a foreground airship, in this case the USS Akron. It captures the locale fulfilling its role as the future's cutting edge, farther ahead of the world than it would ever be again, and just about to be frozen as such by decades of depression, war and recovery.

Architect Raymond Hood began proposing East and Hudson River bridges with 50 to 60 story residential skyscrapers as support pylons in 1925. In 1930 he presented this photomontage of Manhattan densely ringed with residential bridges and interspersed with mountain-like clusters of skyscrapers at selected street intersections. It recalls Louis Biederman's cartoon, New York City as it will be in 1999, both in what it envisions and its title. Hood looked forward only twenty years, calling his project Manhattan 1950. His melding of residential building and bridge is an early step in the direction of 1960s megastructures, monumental frameworks accommodating structure, transportation and all the functions of a city. The megastructure movement reflected architects' conviction at the time of their responsibility to design the whole human environment, a scary prospect indeed.

Reyner Banham astutely identified the appeal of Lower Manhattan as a canvas for new visions of the future. His 1976 book Megastructure is illustrated with this image of Archigram's 1963 Walking City project, showing the conceptual architectural group's walking cities against a backdrop of Wall Street skyscrapers. Banham's caption reads: “Their location here in the East River, with the towers of Manhattan in the background, suggests a deliberate challenge to older visions of the future . . .” By the sixties, Lower Manhattan had become the standard against which to measure urban visions, sealing its own mythic status.

Lower Manhattan's use as a measuring stick for new urban visions followed upon its use as a scale reference. The outline of Albert Kahn Associates' vast Dodge Chicago Aircraft Engine Plant, built for the war effort, was superimposed on Lower Manhattan in the December 1943 issue of The Architectural Forum. While a New Yorker could compare the length of this factory to a walk from the the Battery to the Bowery, the rest of the world could by now relate as well to what had become an iconic cityscape and universal point of reference. The manner in which the plant's outline passes out of sight behind buildings as it weaves among them surpasses the purpose at hand and speaks of this terrain's power to fire the imagination. The image foreshadows visions of city-containing buildings, sometimes rendered as visitors to New York.