Windowflage, part 4

Linked Hybrid, a Beijing complex designed by Steven Holl, was completed last year. As with his Simmons Hall dormitory at MIT, Holl sets windows deeply into a uniform and pervasive grid, camouflaging them as dimples in an enveloping waffle texture that's applied like shrink-wrap. He so accentuates the window grid that it takes on the geometric purity of abstract sculpture. Like many other architects today, Holl hides his windows in plain sight. Unlike so many others, he does this by embracing the grid rather than fleeing it.

Linked Hybrid, a Beijing complex designed by Steven Holl, was completed last year. As with his Simmons Hall dormitory at MIT, Holl sets windows deeply into a uniform and pervasive grid, camouflaging them as dimples in an enveloping waffle texture that's applied like shrink-wrap. He so accentuates the window grid that it takes on the geometric purity of abstract sculpture. Like many other architects today, Holl hides his windows in plain sight. Unlike so many others, he does this by embracing the grid rather than fleeing it.

Georgia O'Keefe's 1927 painting, Radiator Building - Night, New York, shows Raymond Hood's tower at an hour when its dark window openings can't disappear into its black brick façade. The randomness of a city's lit windows at night violates the tyranny of the grid with chance, mystery and individual volition. In recent years, architects have brought this defiance of regimentation into daylight.

Georgia O'Keefe's 1927 painting, Radiator Building - Night, New York, shows Raymond Hood's tower at an hour when its dark window openings can't disappear into its black brick façade. The randomness of a city's lit windows at night violates the tyranny of the grid with chance, mystery and individual volition. In recent years, architects have brought this defiance of regimentation into daylight.

Forty years ahead of its time, an otherwise anonymous 1963 hotel on West 57th Street willfully offsets windows from their expected vertical alignment. The effect is so successful at destroying the usual window grid that the building at first appears to defy structural logic. Only on close inspection does it become apparent that there are still continuous vertical paths for the exterior wall's columns, and that windows are merely jiggled left and right within conventional column bays. While the building's countless identical windows are no less visible and repetitive, they are less suggestive of coercion than windows in a grid, and seem to belong to the liberated realm of surface decoration. Gridding is so much a part of the Gestalt of urban windows that to take them out of alignment camouflages them, effectively hiding them in plain sight.

Forty years ahead of its time, an otherwise anonymous 1963 hotel on West 57th Street willfully offsets windows from their expected vertical alignment. The effect is so successful at destroying the usual window grid that the building at first appears to defy structural logic. Only on close inspection does it become apparent that there are still continuous vertical paths for the exterior wall's columns, and that windows are merely jiggled left and right within conventional column bays. While the building's countless identical windows are no less visible and repetitive, they are less suggestive of coercion than windows in a grid, and seem to belong to the liberated realm of surface decoration. Gridding is so much a part of the Gestalt of urban windows that to take them out of alignment camouflages them, effectively hiding them in plain sight.

SHoP Architects' critically acclaimed Porter House condominium at West 15th Street and Ninth Avenue, completed in 2003, adapted and added onto a 1905 warehouse. The addition roughly matches the bulk of the original building, a key to its success in the role of mirror-opposite. By contrasting itself in every possible way, even offsetting itself from the old building's footprint, the addition leaves the integrity of the original perfectly readable. Among its points of departure, the addition sets its windows free of the grid and varies their width. They are closely enough spaced not to disfavor any of the identical stacked floor plans within on any given floor.

SHoP Architects' critically acclaimed Porter House condominium at West 15th Street and Ninth Avenue, completed in 2003, adapted and added onto a 1905 warehouse. The addition roughly matches the bulk of the original building, a key to its success in the role of mirror-opposite. By contrasting itself in every possible way, even offsetting itself from the old building's footprint, the addition leaves the integrity of the original perfectly readable. Among its points of departure, the addition sets its windows free of the grid and varies their width. They are closely enough spaced not to disfavor any of the identical stacked floor plans within on any given floor.

SHop takes no chances in pusuit of the romantically staggered lit windows of Georgia O'keefe's Radiator Building portrayal. Fixtures built into the addition's face insure a balanced distribution of haphazard light sources, regardless of occupants' contributions.

SHop takes no chances in pusuit of the romantically staggered lit windows of Georgia O'keefe's Radiator Building portrayal. Fixtures built into the addition's face insure a balanced distribution of haphazard light sources, regardless of occupants' contributions.

Polshek Partnership's Standard Hotel, completed last year, straddles the High Line near Washington and West 13th Streets. The building's floor-to-ceiling glass makes the rooms' curtains a facade-determining feature. By day, they contribute the shifting randomness and vitality that variations in artificial lighting typically provide at night.

Polshek Partnership's Standard Hotel, completed last year, straddles the High Line near Washington and West 13th Streets. The building's floor-to-ceiling glass makes the rooms' curtains a facade-determining feature. By day, they contribute the shifting randomness and vitality that variations in artificial lighting typically provide at night.

The Standard Hotel's jiggled window pattern, echoing that of the 1963 hotel pictured above, further defuses the deadening effect of the grid and suggests the decorative freedom of textile design.

The Standard Hotel's jiggled window pattern, echoing that of the 1963 hotel pictured above, further defuses the deadening effect of the grid and suggests the decorative freedom of textile design.

One Ten 3rd, a condominium at 110 Third Avenue, was designed by Greenberg Farrow and completed in 2007. Listing the building's pros and cons, CityRealty cites its "unusual fenestration pattern" as a "con," while New York magazine's Justin Davidson called the building an "impressively awful tower, full of fussy fenestration and clutter." These assessments overlook how efficiently the design avoids gridlock by simply varying the color of the panels covering columns. This variation, within a limited color range, also blends with the predictable chaos of individual owners' window treatments to produce a painterly effect.

One Ten 3rd, a condominium at 110 Third Avenue, was designed by Greenberg Farrow and completed in 2007. Listing the building's pros and cons, CityRealty cites its "unusual fenestration pattern" as a "con," while New York magazine's Justin Davidson called the building an "impressively awful tower, full of fussy fenestration and clutter." These assessments overlook how efficiently the design avoids gridlock by simply varying the color of the panels covering columns. This variation, within a limited color range, also blends with the predictable chaos of individual owners' window treatments to produce a painterly effect.

SOM's addition to John Jay College is approaching completion at Eleventh Avenue between 58th and 59th Streets. Glass units with fritted glass dots in varying densities create patterns that override the framing grid.

SOM's addition to John Jay College is approaching completion at Eleventh Avenue between 58th and 59th Streets. Glass units with fritted glass dots in varying densities create patterns that override the framing grid.

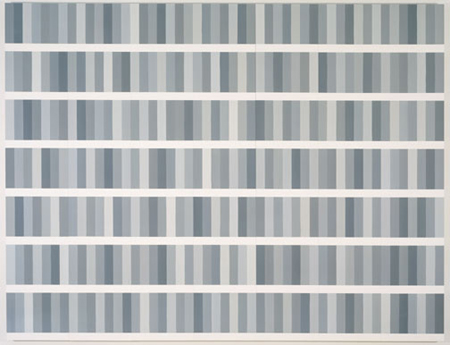

Based on paint manufacturers' color sample chips, Peter Wegner's 2001 painting, 49 Greys, might have inspired SOM's façade at John Jay College. The painting resonates with current architecture's use of the grid as a point of departure for vibrant destinations.

Based on paint manufacturers' color sample chips, Peter Wegner's 2001 painting, 49 Greys, might have inspired SOM's façade at John Jay College. The painting resonates with current architecture's use of the grid as a point of departure for vibrant destinations.

The Zollverein School of Design in Essen, Germany, by SANAA, was completed in 2006. (photo: Michael Hoefner, CC/SA) It practices a different kind of windowflage from the same firm's mesh-encased New Museum of Contemporary Art on the Bowery. Here, windows are set free of the familiar grid in all directions and even deny its possibility by their varied sizes. While emphatically expressed, the windows contribute to, rather than detract from, the overall building as sculpture.

The Zollverein School of Design in Essen, Germany, by SANAA, was completed in 2006. (photo: Michael Hoefner, CC/SA) It practices a different kind of windowflage from the same firm's mesh-encased New Museum of Contemporary Art on the Bowery. Here, windows are set free of the familiar grid in all directions and even deny its possibility by their varied sizes. While emphatically expressed, the windows contribute to, rather than detract from, the overall building as sculpture.

In his "Vision Machine" condominium, nearing completion at West 19th Street and the West Side Highway, Jean Nouvel takes the liberated window into new frontiers. His design not only rejects the grid, but tilts individual glass panels out of planar alignment. Even on the tower's faces that aren't cubist curtainwall, Nouvel's punched windows avoid alignment and consistency of size and shape, as at SANAA's Zollverein School. The building avoids grid-based window radar by multiple means. Beyond, the fritted glass of Frank Gehry's IAC Building catches light like a lampshade.

In his "Vision Machine" condominium, nearing completion at West 19th Street and the West Side Highway, Jean Nouvel takes the liberated window into new frontiers. His design not only rejects the grid, but tilts individual glass panels out of planar alignment. Even on the tower's faces that aren't cubist curtainwall, Nouvel's punched windows avoid alignment and consistency of size and shape, as at SANAA's Zollverein School. The building avoids grid-based window radar by multiple means. Beyond, the fritted glass of Frank Gehry's IAC Building catches light like a lampshade.

The 1960s National Maritime Union annexes at West 17th Street and Ninth Avenue were designed by New Orleans architect Albert Ledner. Beyond their obvious nautical inspiration, the portholes resist interpretation as building windows and contribute to an abstract sculptural quality. Now the Maritime Hotel, the upright annex on the right faces Ninth Avenue and has openings on a standard vertical-horizontal grid. The structure on the left is more relaxed, sloping back from 17th Street and setting its portholes in a diamond array that even further camouflages them into the appearance of decorative surface pattern.

The 1960s National Maritime Union annexes at West 17th Street and Ninth Avenue were designed by New Orleans architect Albert Ledner. Beyond their obvious nautical inspiration, the portholes resist interpretation as building windows and contribute to an abstract sculptural quality. Now the Maritime Hotel, the upright annex on the right faces Ninth Avenue and has openings on a standard vertical-horizontal grid. The structure on the left is more relaxed, sloping back from 17th Street and setting its portholes in a diamond array that even further camouflages them into the appearance of decorative surface pattern.

As rendered by Spine 3D, the West 17th Street Maritime Annex's façade is currently being reworked into an even freer assembly of multi-sized round windows in its conversion to the Dream Downtown Hotel. The redesign, by Frank Fusaro of Handel Architects, argues that even diagonally arrayed round windows aren't up to today's standard of windowflage.

As rendered by Spine 3D, the West 17th Street Maritime Annex's façade is currently being reworked into an even freer assembly of multi-sized round windows in its conversion to the Dream Downtown Hotel. The redesign, by Frank Fusaro of Handel Architects, argues that even diagonally arrayed round windows aren't up to today's standard of windowflage.

Subscribe Us

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a selection of cool articles every weeks