The Farnsworth House, part 2 / from the hearth to the field

Mies van der Rohe prepared renderings of two early versions of the Farnsworth House, one on the ground and the other raised above it. The choice to elevate its floor five feet responded to potential flooding of the nearby Fox River, but also exalted the house, made it appear to float, and gave it the character of a discrete machined object in the landscape, an effect heightened by its abstract whiteness. Raising the house also allowed the equally expressed floor and roof planes to suggest infinite extension of its interior into surrounding space, emphasized by their projection beyond the glass envelope into the open air of the porch. While the house was technologically remarkable for its time, the arresting design mastery at work in such effects have made it an enduring touchstone.

Philip Johnson planted his Glass House on the ground and painted its steel frame black, giving it a recessive quality. Its brown brick floor contributes to the effect of standing on the ground. The Glass House has a much more contained quality than the Farnsworth House, and was designed as part of a compound including a separate guest house. While Johnson never claimed to be a "formgiver like Mies," such distinctive qualities and the many wide-ranging studies by which Johnson arrived at his design mark the Glass House as an original work that stands on its own merits. Johnson was perhaps most significantly original in being the first of many architects to draw inspiration from the Farnsworth House and take its ideas in new directions.

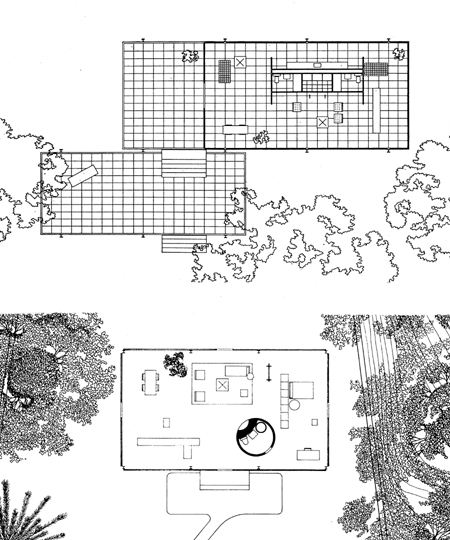

Floor plans show Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House (top) and Philip Johnson's Glass House, in scale with each other. The enclosed portion of the Farnsworth House is at its upper right, the covered porch to its left, and the lower terrace below the porch. The core of the Farnsworth House includes its fireplace, centered on the grouping of chairs, and all of its services, giving the house a clear functional diagram. The core is large enough to make the remaining space in the house read as continuous loop, suggesting an endless spatial flow, and it presses the surrounding space close to the glass envelope and nature. The core of the Glass House includes the bathroom and fireplace but the kitchen is a separate element, treated as a piece of furniture despite being part of the house's support machinery. The cylindrical core's small size and pure shape make it read as an object deposited within a much larger, static space. The greater width and smaller core of the Glass House give it a deeper interior. Johnson said his plan was influenced by a suprematist painting by Kasimir Malevich, and cited several architectural influences in addition to the Farnsworth House.

A replica of Thoreau's cabin at Walden Pond. Building from discarded shingles, second-hand windows and used bricks, and providing his own labor, Thoreau built his house for twenty-eight dollars, twelve and a half cents. (The Farnsworth House cost $73,000 in 1951.) Thoreau's spirit has guided many of the architects who've carried forward ideas from the Farnsworth House, often in more sustainable directions.

Comparing their one-room houses, Thoreau's measured 15 by 10 feet; Johnson's 56 by 32 feet; and Mies's 56 feet by 28 feet, 8 inches (without the porch). Thoreau conceded that "one inconvenience I sometimes experienced in so small a house, the difficulty of getting to a sufficient distance from my guest when we began to utter big thoughts in big words." He also wrote that "I sometimes dream of a larger and more populous house, standing in a golden age, of enduring materials, and without gingerbread work, which shall consist of only one room . . . A house whose inside is open and manifest as a bird's nest. . . ."

By limiting the Farnsworth House to a single room, Mies answered the concern Johnson had raised about interior partitions colliding with a pristine glass perimeter, but he also realized Thoreau's dream of a one-room house, a dream that many architects have found compelling. In his biography of Johnson, Franz Schulze describes his response to this aspect of the Farnsworth House: "Philip was moved by the exquisiteness of the design but just as instructed by Mies's simple decision to consolidate all interior elements - kitchen, closets, a pair of bathrooms - in a core, no part of which abutted the outer walls. The walls could thus be composed of a material as fragile as glass; the only cost would be an unpartitioned interior, a condition Philip found less a defect than a boon."

The Farnsworth House's core doesn't present itself as an island cluster of separate rooms, but as a discrete object. By rising to a level just short of the main space's ceiling, it suggests a piece of freestanding furniture. In similar fashion, Johnson's bathroom enclosure, by also housing a fireplace, is made to read as a chimney. These effects disguise the presence of interior rooms and enforce the sense of a one-room house.

The appeal of one-room buildings lies in their direct relationship between envelope and content, in the primally satisfying simplicity of a one-to-one relationship between exterior and interior. Their lineage includes ancient temples, the Pantheon, Bramante's Tempietto and Thoreau's cabin. In the 1980s, Frank Gehry tried to capture the integrity of such buildings in projects like his 1981 "House for a Filmmaker", which adopts the form of a cluster of individual buildings. Describing his motive for the house's design in the 1986 Walker Art Center book, The Architecture of Frank Gehry, he wrote, "I thought that by minimizing the issue of function, by creating one-room buildings, we could resolve the most difficult problems in architecture. Think of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings ever built are one-room buildings." The idea formed the basis of the "village of forms" model on which Gehry would design many projects.

A replica of Thoreau's cabin at Walden Pond. Building from discarded shingles, second-hand windows and used bricks, and providing his own labor, Thoreau built his house for twenty-eight dollars, twelve and a half cents. (The Farnsworth House cost $73,000 in 1951.) Thoreau's spirit has guided many of the architects who've carried forward ideas from the Farnsworth House, often in more sustainable directions.

Comparing their one-room houses, Thoreau's measured 15 by 10 feet; Johnson's 56 by 32 feet; and Mies's 56 feet by 28 feet, 8 inches (without the porch). Thoreau conceded that "one inconvenience I sometimes experienced in so small a house, the difficulty of getting to a sufficient distance from my guest when we began to utter big thoughts in big words." He also wrote that "I sometimes dream of a larger and more populous house, standing in a golden age, of enduring materials, and without gingerbread work, which shall consist of only one room . . . A house whose inside is open and manifest as a bird's nest. . . ."

By limiting the Farnsworth House to a single room, Mies answered the concern Johnson had raised about interior partitions colliding with a pristine glass perimeter, but he also realized Thoreau's dream of a one-room house, a dream that many architects have found compelling. In his biography of Johnson, Franz Schulze describes his response to this aspect of the Farnsworth House: "Philip was moved by the exquisiteness of the design but just as instructed by Mies's simple decision to consolidate all interior elements - kitchen, closets, a pair of bathrooms - in a core, no part of which abutted the outer walls. The walls could thus be composed of a material as fragile as glass; the only cost would be an unpartitioned interior, a condition Philip found less a defect than a boon."

The Farnsworth House's core doesn't present itself as an island cluster of separate rooms, but as a discrete object. By rising to a level just short of the main space's ceiling, it suggests a piece of freestanding furniture. In similar fashion, Johnson's bathroom enclosure, by also housing a fireplace, is made to read as a chimney. These effects disguise the presence of interior rooms and enforce the sense of a one-room house.

The appeal of one-room buildings lies in their direct relationship between envelope and content, in the primally satisfying simplicity of a one-to-one relationship between exterior and interior. Their lineage includes ancient temples, the Pantheon, Bramante's Tempietto and Thoreau's cabin. In the 1980s, Frank Gehry tried to capture the integrity of such buildings in projects like his 1981 "House for a Filmmaker", which adopts the form of a cluster of individual buildings. Describing his motive for the house's design in the 1986 Walker Art Center book, The Architecture of Frank Gehry, he wrote, "I thought that by minimizing the issue of function, by creating one-room buildings, we could resolve the most difficult problems in architecture. Think of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings ever built are one-room buildings." The idea formed the basis of the "village of forms" model on which Gehry would design many projects.

An illustration from Lester Walker's American Shelter (Overlook Press, 1997) shows early American house construction that prefigures the core-and-envelope formula of the Farnsworth House and Glass House. "I lingered most about

An illustration from Lester Walker's American Shelter (Overlook Press, 1997) shows early American house construction that prefigures the core-and-envelope formula of the Farnsworth House and Glass House. "I lingered most about  Reducing the Farnsworth House to a single room, Mies kept his glass envelope pure, appealed to innate domestic desires, and minimized the distance Thoreau regretted had grown "from the hearth to the field." continued

Reducing the Farnsworth House to a single room, Mies kept his glass envelope pure, appealed to innate domestic desires, and minimized the distance Thoreau regretted had grown "from the hearth to the field." continued

Subscribe Us

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a selection of cool articles every weeks