Nouvel's Tower Verre Not the Only Vision in the Hearing Room

Rendering of Jean Nouvel's Tower Verre

Nouvel's tower has received praise from critics and criticism from community groups, even as Hines, its giant international developer, has advanced the project through review processes and closer to realization. MoMA sold the site to Hines for $125 million in a deal that will cede 39,500 square feet of space in the new building back to the museum for galleries. MoMA director Glenn Lowry pointed out in the hearing that the double-height second floor of the new tower will be especially useful to the museum for exhibition of large works by sculptors like Richard Serra and Martin Puryear. Opponents of the tower have generally addressed its great height. Community members at yesterday's hearings called it colossal, outrageously tall, and - of course - an oversized phallus.

Hugh Ferriss's rendering of William Van Alen's Chrysler Building

It's been noted that Nouvel's 82-story building will exceed the height of the Chrysler Building, an icon that in some ways haunts the discussion. Perhaps the ultimate in pointy skyscrapers, the Chrysler Building was rendered by Ferriss approaching completion, its top still an open steel framework through which daylight can be seen. Nouvel spoke of his building yesterday as a "skeleton" and "also a dream", balancing materiality and immateriality. "It has to disappear into the sky", he said, in terms that seem to have Ferriss's incomplete Chrysler in mind. While Nouvel's renderings don't particularly exploit this characteristic, the building's framing suggests how it might be achieved at the peak.

Tower Verre's framing model suggests how its top might be dematerialized by penetrating light.

The dissolving quality that Nouvel described would mitigate somewhat the impact of what is, after all, not the Chrysler Building but a nearly quarter-mile tall glass sheath. This hermetic quality and the building's height are behind architect John Beckmann's denunciation of it at yesterday's hearing as a "glass spike driven into the heart of New York City". Beckmann proceeded to put his money where his mouth is by presenting an alternate scheme that satisfies the same program in thirty fewer stories and in a more permeable form.

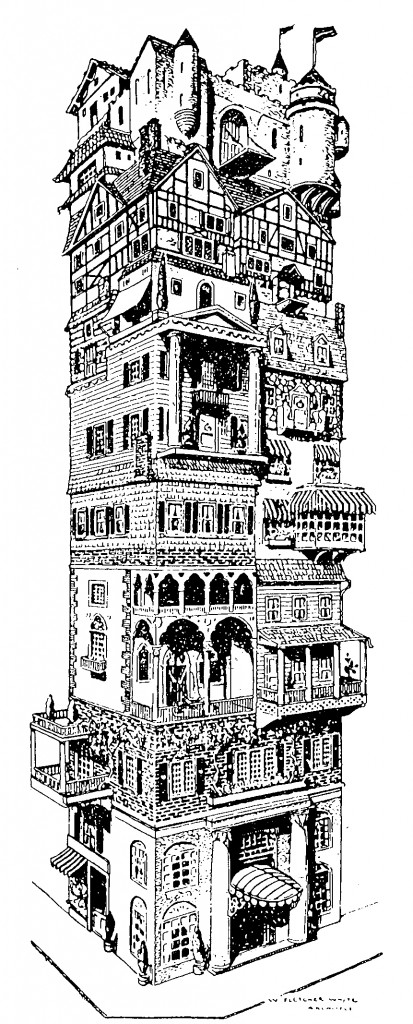

An alternate MoMA tower proposal by architect John Beckmann and his firm, Axis Mundi

With open arcades at sidewalk level, and seemingly composed entirely of nooks and crannies, Beckmann's building at first appears to be riding the trend for jiggled-box compositions like Herzog & de Meuron's 56 Leonard Street project, but on closer inspection has a more open character, with through-building openings aloft, and elevated gardens, similar to Moshe Safdie's Habitat '67, as well as exterior stairways. This upper level sponginess may not allow any greater access to the man on the street, but it invites imaginative penetration of the sort architect Robert Yudell described as the antidote to the curtain-wall skyscraper, of which he wrote: "We can neither measure ourselves against it nor imagine a bodily participation. Our bodily response is reduced to little more than a craned head, wide eyes, and perhaps an open jaw in appreciation of some magnificent height or some elegantly prescribed mullion detailing. Compare this with a 1920s ziggurat skyscraper such as the Chrysler Building. Here we have not only the vertical differentiation of the building but chunky setbacks which conjure landscapes or grand stairways. We can imagine scaling, leaping, and occupying its surfaces and interstices. Even the cheap and efficient stepped-back curtain-wall buildings erected along New York's City's Park Avenue in the 1950s and 1960s provide us with some form of cubic landscape."*

Robert Yudell illustrated his essay criticizing curtain wall skyscrapers with "King's Dream of New York", a 1908 fantasy rendering that shows a population almost hyperactively engaged with its city.

Rem Koolhaas used this seminal 1909 Life magazine cartoon in "Delirious New York".

A year later, Rem Koolhaas would illustrate Delirious New York with "King's Dream of New York" and a 1909 Life magazine cartoon that shows conventional houses stacked one per floor on an open steel skyscraper frame. It is this latter image that Koolhaas mines for a rich payload of ideology. Calling it "a theorem that describes the ideal performance of the Skyscraper", Koolhaas says: "The structure is a whole exactly to the extent that the individuality of the platforms is preserved and exploited, that its success should be measured by the degree to which the structure frames their coexistence without interfering with their destinies. The building becomes a stack of individual privacies. . . Villas may go up and collapse, other facilities may replace them, but that will not affect the framework. . . An unforeseeable and unstable combination of simultaneous activities . . . makes architecture less an act of foresight than before and planning an act of only limited prediction." ** The same cartoon directly inspired James Wines and his firm SITE's 1980s Highrise of Homes project, which sought to reconcile the "overbearing" highrise with a "flexible and responsive habitat for urban dwellers".***

SITE's Highrise of Homes

As Beckmann told ArchiTakes yesterday, the exteriors of individual units in his tower could be customized by residents for personal expression and flexibility of use. There's an irresistible appeal both in the individual liberation of this and in the idea of the building as an uncontrolled rotating exhibit attached to the museum. The resulting collage would respond to popular impulses that have been around in cartoons for a century, and which thrive in today's art world. Beckmann's thought provoking alternative won't derail Nouvel's tower, but it substantiates his criticism that there are other ways. It's also worth remembering the power of a picture, as witnessed by Ferriss's influence on Nouvel and an old cartoon's on Koolhaas and his entire orbit. Architecture in New York could use more of the grassroots initiative Beckmann has shown and more of the debate he hopes to inspire.

This 1920 cartoon also inspired SITE's Highrise of Homes.

Dionisio Gonzalez's "Nova Heliopolis II" might have taken inspiration from the cartoon above. Artists like Gonzalez, Laura S. Kicey and Kobas Laksa are among many who depict collage-buildings.

* Body, Memory and Architecture,by Kent C. Bloomer, Charles W. Moore and Robert J. Yudell, Yale, 1977 (pp.61-64)

** Delirious New York, by Rem Koolhaas, Oxford, 1978 (pp.69-70)

*** Highrise of Homes, by SITE, Rizzoli, 1982 (p.11)