Stanford White's Bronx Pantheon To Lose Pride of Place

- Gould Memorial Library, 1894-99, is called "one of Stanford White's most important achievements" by his biographer, Paul R. Baker.

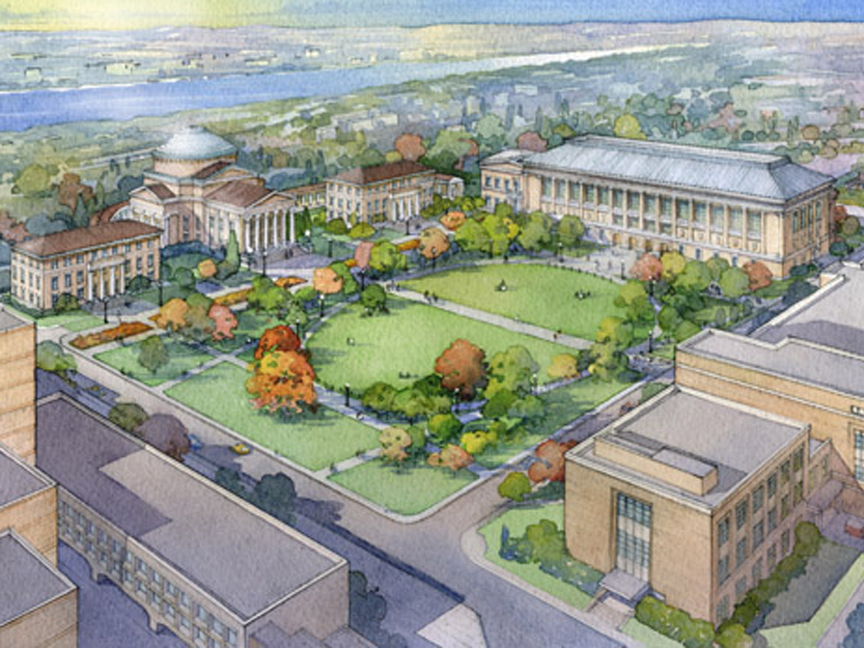

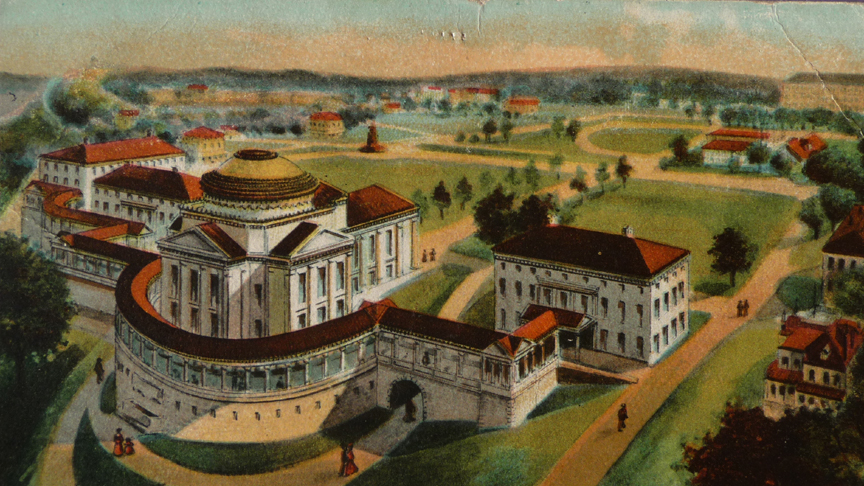

Ground has been broken on a new Bronx Community College building by Robert A.M. Stern that will leave Stanford White's Gould Memorial Library off-center on its historic quadrangle. Part of the City University of New York, the college occupies what was originally the north campus of New York University. Stanford White designed a campus master plan for NYU in the 1890's, and four structures designed by him were built according to it. They formed the head of a proposed quadrangle inspired by Thomas Jefferson's design for the University of Virginia. The structures built to White's design are Gould Memorial Library, two flanking academic halls and the crescent-shaped Hall of Fame colonnade centered behind them. The library is modeled on the Pantheon in Rome, and faces a central Great Lawn as conceived in White's master plan. The Guide to New York City Landmarks describes the library as "one of White's greatest buildings" - an almost universal appraisal - and notes that "the importance of this design in White's work was recognized in 1919 when his peers chose to create a pair of bronze doors for the library as a White memorial". Buildings introduced since White's time have roughly followed his master plan on the south and east sides of the quadrangle, producing the Great Lawn he planned. The north side of the Lawn has remained vacant, used as a parking lot, until now. About to rise on this site is the new North Instructional Building and Library, designed by Robert A.M. Stern Architects. Stern's design will cover not just the area allocated for buildings in White's master plan, but much of the Great Lawn as well. Encroached upon by the new building, what is left of the Lawn will be off-center with the library, destroying the fundamental premise of White's master plan and devaluing one of the nation's most architecturally significant campus cores. Unlike White's structures, the Great Lawn is not protected by landmark designation, a particularly regrettable oversight on the part of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. The Lawn and the structures were conceived as a piece, open space and buildings reinforcing each other's importance. As the exterior focus of the campus, the Great Lawn is intentionally aligned with its interior focus, the library's great rotunda, their classically symmetrical spaces linked and sequentially experienced by way of a processional path centered on Lawn and buildings. A patently organic part of the total design, the Lawn is certainly as worthy of designation as the buildings whose quality it enhances. Had it been designated, construction on the Great Lawn would certainly never have been allowed by the Landmarks Commission. Lacking designation, the Lawn depended on CUNY's responsible stewardship and its hired architects' accountability for preservation.

The siting of the new building contradicts recommendations of a 2005 Conservation Master Plan prepared by the firm Heritage Landscapes under a $228,000 grant from the Getty Trust. This document, on view at the Getty Center, states that its "high priority . . . is to highlight possible locations of future buildings with respect to historic configurations and character-defining features". It says of one proposed building, which would eventually be Stern's, in particular: "Some discussion about siting the building on the current north parking lot has also ensued. The preservation conservation team recommends the proposed building be constructed on the site to the north across the Hall of Fame Terrace, not on the site of the north parking lot

- Stanford White's 1892 master plan shows a wide Great Lawn centered on Gould Memorial Library and the Hall of Fame Terrace at top. The structures across the top of the Lawn were built to White's design. Buildings shown at the sides and bottom of the Lawn show White's proposed locations for future buildings.

- Frederick Law Olmsted Jr's 1912 master plan moves proposed side buildings closer to the center of the Great Lawn, substantially narrowing it. This plan was never implemented, and later buildings were located in line with White's original master plan on the left side and bottom of the Lawn, while the right side remained vacant.

- Robert A.M. Stern's 2006 master plan shows existing buildings at top, left and bottom and his new building at right. The left side of the Lawn corresponds to White's planned boundaries for it, the right side to Olmsted Jr's.

This double-talk can't hide what's plain as day on any drawing of the new campus plan, the negation of White's larger concept and the diminishment of his library's primacy. The new building isn't just in the wrong place; its scale is far greater than what White had envisioned and suggested by way of the academic halls he designed on either side of Gould Memorial Library. (Had CUNY only heard of Stern's academic credentials and not his ego?)

What kind of building does the College get for $56 million and an imponderable loss of cultural heritage? A giant knockoff of Henri Labrouste's Bibliotheque Ste. Genevieve, phoned in with minimal adjustment to program and site. The first floor contains giant classrooms that speak of unconscionable teacher-student ratios, with tiny windows so they can stand in for Labrouste's first floor stacks and offices. This masquerade takes priority over green architecture considerations like the proven benefit of natural light to classroom learning. (Stern's website touts the building's LEED Silver status as if it weren't the minimum level required by New York City law.) Upstairs, the new library has 45 foot ceilings, producing a huge volume of unused space that contributes greatly to the building's overreaching bulk. CUNY would certainly have better spent the public's money finding a way to put Gould's spectacular interior to more vital use. The rationale for Labrouste's Bibliotheque as Stern's model? It inspired Charles McKim in his design of the Boston Public Library, and McKim was Stanford White's partner in the firm of McKim, Mead & White. As with the "Olmsted connection", associations make it right. Here's an association that CUNY Chancellor Matthew Goldstein might contemplate as he hands White's campus over to Stern; in 1981 the great architecture critic and historian Reyner Banham published a dual book review ("The Ism Count" in New Society) of the Academy Editions monograph, Robert Stern, and Whiffen and Koeper's survey, American Architecture 1607-1976. After noting Stern's "complete lack of aesthetic scruple" and "an almost complete lack of congruence between his facades and his plans", Banham asks, "what's it all got to do with 'real architecture'?" He notes that Stern doesn't rate a mention in American Architecture, which he proceeds to test for trendiness by checking the percentage of its pages dedicated to McKim, Mead & White, then riding a wave of resurgent interest. Banham finds that the book allots Stanford White's firm two percent of its page count, "perhaps even over-compensating for current fads in historiography, though the text is full of appreciation of the real virtues and qualities of their best works". Banham ends by wondering whether American Architecture "may go through enough editions over the years to find a place for Bob Stern and Post-Modernism" and concludes, "I wouldn't like to bet what percentage of the page count they will get". Banham was right that Stern would never be recognized for "real architecture", but could hardly have imagined what a reputation he'd build on make-believe. It's New York's loss that CUNY can't tell the difference.

Subscribe Us

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a selection of cool articles every weeks