Convergences

Influential "Life" Cartoon Turns 100

In the 1980s, Walker's Life cartoon inspired the "Highrise of Homes" project by James Wines and his firm SITE, a fantasy of highrise housing that would allow individual freedom and expression. As described in SITE's Highrise of Homes publication (Rizzoli, 1982, p.41), "The two most obvious antecedents for the Highrise of Homes are the amusing 1909 drawing of a proposal for a skyscraper as a utopian device and the 1920 fantasy depicting a cooperative apartment house built according to the owners' individual tastes. It should be noted, however, that these examples point up the difference between a casual joke and a topic of substantive research, and have been included here with hopes that a comparison of intent will work in favor of a better understanding of the Highrise of Homes." While this statement fails to acknowledge how literally the project builds on Walker's image, SITE's fleshing out of his cartoon's outlines and dense proliferation of its plantings transforms the cartoon into a different kind of art and anticipates a trend found in today's green skyscraper proposals.

In the 1980s, Walker's Life cartoon inspired the "Highrise of Homes" project by James Wines and his firm SITE, a fantasy of highrise housing that would allow individual freedom and expression. As described in SITE's Highrise of Homes publication (Rizzoli, 1982, p.41), "The two most obvious antecedents for the Highrise of Homes are the amusing 1909 drawing of a proposal for a skyscraper as a utopian device and the 1920 fantasy depicting a cooperative apartment house built according to the owners' individual tastes. It should be noted, however, that these examples point up the difference between a casual joke and a topic of substantive research, and have been included here with hopes that a comparison of intent will work in favor of a better understanding of the Highrise of Homes." While this statement fails to acknowledge how literally the project builds on Walker's image, SITE's fleshing out of his cartoon's outlines and dense proliferation of its plantings transforms the cartoon into a different kind of art and anticipates a trend found in today's green skyscraper proposals.

Last year's proposal by architect Daniel Libeskind for a the residential Madison Square Park Tower is one of several recent highrise designs that incorporate trees in a way never dreamt of by the office ficus, and first envisioned in Walker's Life cartoon. An emerging breed of environmentally minded skysrapers wear green on their sleeves.

Last year's proposal by architect Daniel Libeskind for a the residential Madison Square Park Tower is one of several recent highrise designs that incorporate trees in a way never dreamt of by the office ficus, and first envisioned in Walker's Life cartoon. An emerging breed of environmentally minded skysrapers wear green on their sleeves.

UCX Architects' Urban Cactus apartment tower, under construction in Rotterdam, may be the closest thing ever built to a realization of Walker's concept.

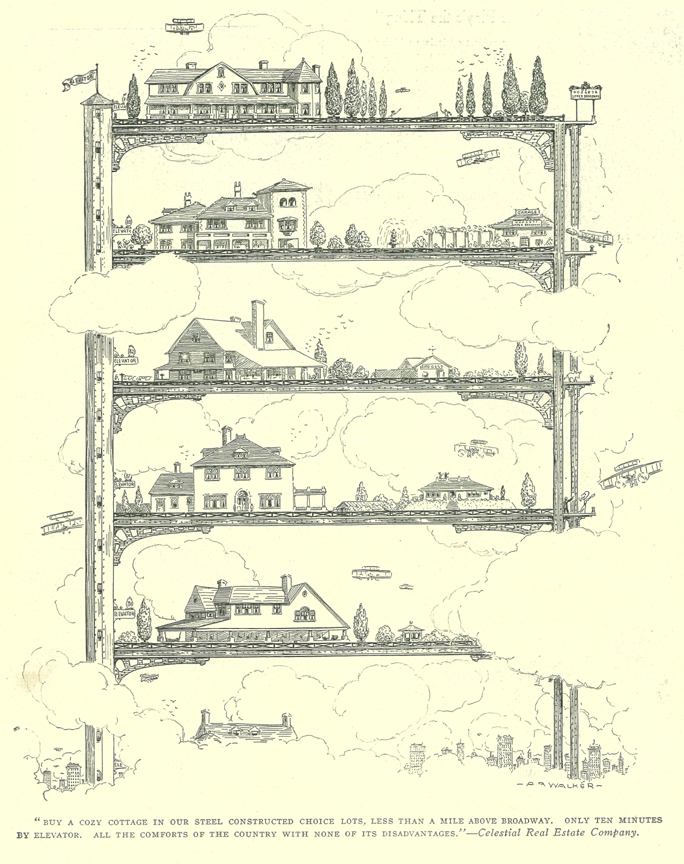

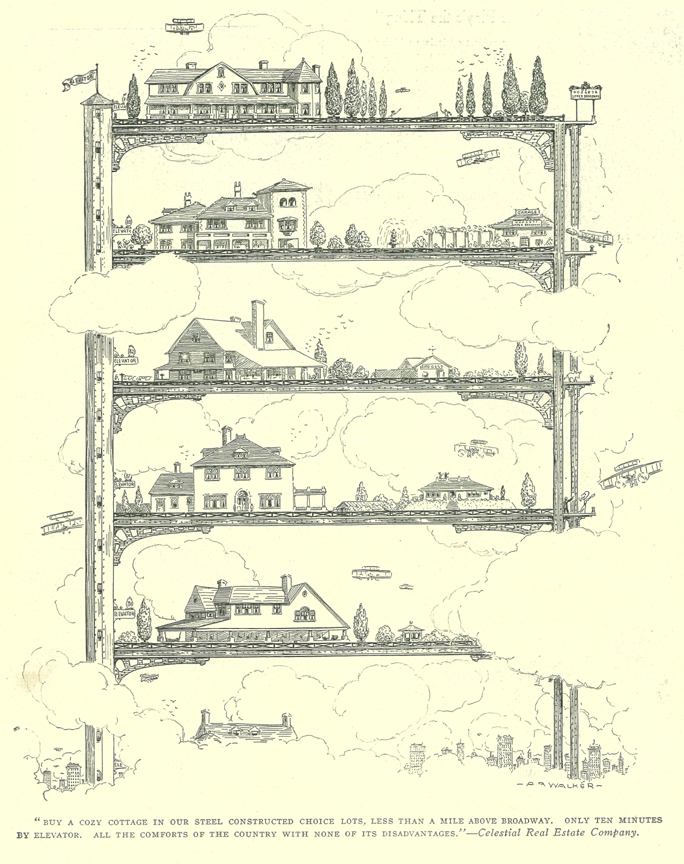

Placing the cartoon in its original context of Life's 1909 "Real Estate Number" not only reminds us how long New York has been obsessed with this topic, but gives us a glimpse of New York's early awareness of itself as a skyscraper city. Including the cover image, the issue's half-dozen skyscraper cartoons all exaggerate distance from the ground. (Transportation among towers by aircraft is another of their themes, which seems to have had enough serious currency to have inspired the real-life zeppelin mooring mast atop the Empire State Building and the rooftop helipad of the Pan Am - now MetLife - Building.) What sets Walker's houses-on-steel-frame cartoon apart from the others is its commentary on the home's loss of immediate connection to the ground. When the first skyscrapers were rising, apartment buildings were still a recent phenomenon. As described in New York: An Illustrated History by Ric Burns, James Sanders and Lisa Ades (Knopf, 2003, p.236), "From the very start, the new structures generated controversy. One resident of the Upper East Side voiced the opinion of many prosperous New Yorkers - nearly all of whom still lived in private row houses - when he declared that 'Gentlemen will never consent to live on mere shelves under a common roof'."

An early apartment building, The Dakota, was designed with apartments the size of single-family row houses to entice early adopters of apartment living. Walker's cartoon reflects on what was most fundamentally false about this promise, the lack of contact with the ground. On an entirely separate path, his image's openness to interpretation has given it a life he could never have imagined.

UCX Architects' Urban Cactus apartment tower, under construction in Rotterdam, may be the closest thing ever built to a realization of Walker's concept.

Placing the cartoon in its original context of Life's 1909 "Real Estate Number" not only reminds us how long New York has been obsessed with this topic, but gives us a glimpse of New York's early awareness of itself as a skyscraper city. Including the cover image, the issue's half-dozen skyscraper cartoons all exaggerate distance from the ground. (Transportation among towers by aircraft is another of their themes, which seems to have had enough serious currency to have inspired the real-life zeppelin mooring mast atop the Empire State Building and the rooftop helipad of the Pan Am - now MetLife - Building.) What sets Walker's houses-on-steel-frame cartoon apart from the others is its commentary on the home's loss of immediate connection to the ground. When the first skyscrapers were rising, apartment buildings were still a recent phenomenon. As described in New York: An Illustrated History by Ric Burns, James Sanders and Lisa Ades (Knopf, 2003, p.236), "From the very start, the new structures generated controversy. One resident of the Upper East Side voiced the opinion of many prosperous New Yorkers - nearly all of whom still lived in private row houses - when he declared that 'Gentlemen will never consent to live on mere shelves under a common roof'."

An early apartment building, The Dakota, was designed with apartments the size of single-family row houses to entice early adopters of apartment living. Walker's cartoon reflects on what was most fundamentally false about this promise, the lack of contact with the ground. On an entirely separate path, his image's openness to interpretation has given it a life he could never have imagined.

Influential "Life" Cartoon Turns 100

In the 1980s, Walker's Life cartoon inspired the "Highrise of Homes" project by James Wines and his firm SITE, a fantasy of highrise housing that would allow individual freedom and expression. As described in SITE's Highrise of Homes publication (Rizzoli, 1982, p.41), "The two most obvious antecedents for the Highrise of Homes are the amusing 1909 drawing of a proposal for a skyscraper as a utopian device and the 1920 fantasy depicting a cooperative apartment house built according to the owners' individual tastes. It should be noted, however, that these examples point up the difference between a casual joke and a topic of substantive research, and have been included here with hopes that a comparison of intent will work in favor of a better understanding of the Highrise of Homes." While this statement fails to acknowledge how literally the project builds on Walker's image, SITE's fleshing out of his cartoon's outlines and dense proliferation of its plantings transforms the cartoon into a different kind of art and anticipates a trend found in today's green skyscraper proposals.

In the 1980s, Walker's Life cartoon inspired the "Highrise of Homes" project by James Wines and his firm SITE, a fantasy of highrise housing that would allow individual freedom and expression. As described in SITE's Highrise of Homes publication (Rizzoli, 1982, p.41), "The two most obvious antecedents for the Highrise of Homes are the amusing 1909 drawing of a proposal for a skyscraper as a utopian device and the 1920 fantasy depicting a cooperative apartment house built according to the owners' individual tastes. It should be noted, however, that these examples point up the difference between a casual joke and a topic of substantive research, and have been included here with hopes that a comparison of intent will work in favor of a better understanding of the Highrise of Homes." While this statement fails to acknowledge how literally the project builds on Walker's image, SITE's fleshing out of his cartoon's outlines and dense proliferation of its plantings transforms the cartoon into a different kind of art and anticipates a trend found in today's green skyscraper proposals.

Last year's proposal by architect Daniel Libeskind for a the residential Madison Square Park Tower is one of several recent highrise designs that incorporate trees in a way never dreamt of by the office ficus, and first envisioned in Walker's Life cartoon. An emerging breed of environmentally minded skysrapers wear green on their sleeves.

Last year's proposal by architect Daniel Libeskind for a the residential Madison Square Park Tower is one of several recent highrise designs that incorporate trees in a way never dreamt of by the office ficus, and first envisioned in Walker's Life cartoon. An emerging breed of environmentally minded skysrapers wear green on their sleeves.

UCX Architects' Urban Cactus apartment tower, under construction in Rotterdam, may be the closest thing ever built to a realization of Walker's concept.

Placing the cartoon in its original context of Life's 1909 "Real Estate Number" not only reminds us how long New York has been obsessed with this topic, but gives us a glimpse of New York's early awareness of itself as a skyscraper city. Including the cover image, the issue's half-dozen skyscraper cartoons all exaggerate distance from the ground. (Transportation among towers by aircraft is another of their themes, which seems to have had enough serious currency to have inspired the real-life zeppelin mooring mast atop the Empire State Building and the rooftop helipad of the Pan Am - now MetLife - Building.) What sets Walker's houses-on-steel-frame cartoon apart from the others is its commentary on the home's loss of immediate connection to the ground. When the first skyscrapers were rising, apartment buildings were still a recent phenomenon. As described in New York: An Illustrated History by Ric Burns, James Sanders and Lisa Ades (Knopf, 2003, p.236), "From the very start, the new structures generated controversy. One resident of the Upper East Side voiced the opinion of many prosperous New Yorkers - nearly all of whom still lived in private row houses - when he declared that 'Gentlemen will never consent to live on mere shelves under a common roof'."

An early apartment building, The Dakota, was designed with apartments the size of single-family row houses to entice early adopters of apartment living. Walker's cartoon reflects on what was most fundamentally false about this promise, the lack of contact with the ground. On an entirely separate path, his image's openness to interpretation has given it a life he could never have imagined.

UCX Architects' Urban Cactus apartment tower, under construction in Rotterdam, may be the closest thing ever built to a realization of Walker's concept.

Placing the cartoon in its original context of Life's 1909 "Real Estate Number" not only reminds us how long New York has been obsessed with this topic, but gives us a glimpse of New York's early awareness of itself as a skyscraper city. Including the cover image, the issue's half-dozen skyscraper cartoons all exaggerate distance from the ground. (Transportation among towers by aircraft is another of their themes, which seems to have had enough serious currency to have inspired the real-life zeppelin mooring mast atop the Empire State Building and the rooftop helipad of the Pan Am - now MetLife - Building.) What sets Walker's houses-on-steel-frame cartoon apart from the others is its commentary on the home's loss of immediate connection to the ground. When the first skyscrapers were rising, apartment buildings were still a recent phenomenon. As described in New York: An Illustrated History by Ric Burns, James Sanders and Lisa Ades (Knopf, 2003, p.236), "From the very start, the new structures generated controversy. One resident of the Upper East Side voiced the opinion of many prosperous New Yorkers - nearly all of whom still lived in private row houses - when he declared that 'Gentlemen will never consent to live on mere shelves under a common roof'."

An early apartment building, The Dakota, was designed with apartments the size of single-family row houses to entice early adopters of apartment living. Walker's cartoon reflects on what was most fundamentally false about this promise, the lack of contact with the ground. On an entirely separate path, his image's openness to interpretation has given it a life he could never have imagined.

Plug-in Architecture Loses an Icon

With Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower (photo: Scarletgreen/Flickr) headed for demolition, the world will lose not just one of the few executed works of Japanese Metabolism, as noted earlier this month by Nicolai Ouroussoff in the New York Times, but a rare built example of plug-in architecture. The Capsule Tower might at first appear no more than a quaint, dated vision of the future, but a look at its durable influence and vital legacy show an icon of growing historic significance whose loss will loom larger in the years to come.

With Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower (photo: Scarletgreen/Flickr) headed for demolition, the world will lose not just one of the few executed works of Japanese Metabolism, as noted earlier this month by Nicolai Ouroussoff in the New York Times, but a rare built example of plug-in architecture. The Capsule Tower might at first appear no more than a quaint, dated vision of the future, but a look at its durable influence and vital legacy show an icon of growing historic significance whose loss will loom larger in the years to come.

A tower of plug-in "capsule" homes was designed by Archigram's Warren Chalk in 1964. Inspired by space capsules, Chalk's prefabricated dwelling modules would plug into a central shaft providing structural support, vertical circulation and services. Capsule living units would be replaced by a top-mounted crane as newer models evolved, using automobiles as an analogy. Of Archigram's concepts, this one most closely corresponds to any of the few Japanese Metabolist projects actually to be built, Nakagin Capsule Tower.

A tower of plug-in "capsule" homes was designed by Archigram's Warren Chalk in 1964. Inspired by space capsules, Chalk's prefabricated dwelling modules would plug into a central shaft providing structural support, vertical circulation and services. Capsule living units would be replaced by a top-mounted crane as newer models evolved, using automobiles as an analogy. Of Archigram's concepts, this one most closely corresponds to any of the few Japanese Metabolist projects actually to be built, Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Cranes of the Port Newark Container Terminal loom beyond a Bayonne, New Jersey, trailer park. Off the architectural high road, trailer parks have long implemented the ideal of mass produced dwelling units plugged into a fixed infrastructure. Trailers take the concept a step further by allowing homes to easily relocate from one infrastructure to another. On a separate real-world track, shipping container technology, with its industrialized capsules constantly rearranged by cranes, parallels the ideas of Archigram.

The firm LO-TEK, in its multiple Modular Dwelling Unit proposal of 2002, applies container technology to the mobile home precedent by way of a vertical support framework that would realize Le Corbusier's wine rack analogy, with shipping containers retrofitted into homes serving as the bottles. LOT-EK's concept includes drawer-like "subvolumes" that pull out from each container's body, admitting natural light and creating activity areas larger than the containers' 8-foot width. The vertical frames, or "harbors" include stairs, elevators and services. Harbors would be located in all major metropolitan areas to maximize mobility. The sustainability of this system begins with repurposing of containers and continues with mobility of dwellings. The naturally varied appearance of recycled containers corresponds to Corbusier's use of different colors on the exterior of the Unite d'Habitations to identify individual dwelling units. Or as LO-TEK puts it, “The vertical harbor is in constant transformation as MDUs are loaded and unloaded from the permanent rack. Like pixels in a digital image, temporary patterns are generated by the presence or absence of MDUs in different locations along the rack, reflecting the ever-changing composition of these colonies scattered around the globe.” While many real projects, including a hotel, have taken advantage of containers' stackable-by-design character, LOT-EK's use of a separate frame would allow true plug-in flexibility.

Echoing Archigram's Plug-in City, the cranes endemic to container yards would insert or withdraw living capsules. The fixed frame proposed by LO-TEK corresponds to Le Corbusier's "wine rack".

Freitag's shop in Zurich, 2005, takes advantage of the native stackability of containers. The company's product line of bags made from recycled truck tarps is inspired by the same ideas of recycling, found-object-art, and industrial chic that inform container architecture. Enough notable examples and practitioners of this architecture, including work by pioneers like Wes Jones and Adam Kalkin, have emerged to warrant a book-length survey, Container Architecture, by Jure Kotnik (LINKS, 2008). The movement taps into the recent explosion of interest in prefab house design, which itself signals a growing public enthusiasm for the application to housing of mass production's potential for quality control, economy, and consumer choice. This promise has always been central to the plug-in school of thought, and Le Corbusier's vision of the house as "machine for living".

Cranes of the Port Newark Container Terminal loom beyond a Bayonne, New Jersey, trailer park. Off the architectural high road, trailer parks have long implemented the ideal of mass produced dwelling units plugged into a fixed infrastructure. Trailers take the concept a step further by allowing homes to easily relocate from one infrastructure to another. On a separate real-world track, shipping container technology, with its industrialized capsules constantly rearranged by cranes, parallels the ideas of Archigram.

The firm LO-TEK, in its multiple Modular Dwelling Unit proposal of 2002, applies container technology to the mobile home precedent by way of a vertical support framework that would realize Le Corbusier's wine rack analogy, with shipping containers retrofitted into homes serving as the bottles. LOT-EK's concept includes drawer-like "subvolumes" that pull out from each container's body, admitting natural light and creating activity areas larger than the containers' 8-foot width. The vertical frames, or "harbors" include stairs, elevators and services. Harbors would be located in all major metropolitan areas to maximize mobility. The sustainability of this system begins with repurposing of containers and continues with mobility of dwellings. The naturally varied appearance of recycled containers corresponds to Corbusier's use of different colors on the exterior of the Unite d'Habitations to identify individual dwelling units. Or as LO-TEK puts it, “The vertical harbor is in constant transformation as MDUs are loaded and unloaded from the permanent rack. Like pixels in a digital image, temporary patterns are generated by the presence or absence of MDUs in different locations along the rack, reflecting the ever-changing composition of these colonies scattered around the globe.” While many real projects, including a hotel, have taken advantage of containers' stackable-by-design character, LOT-EK's use of a separate frame would allow true plug-in flexibility.

Echoing Archigram's Plug-in City, the cranes endemic to container yards would insert or withdraw living capsules. The fixed frame proposed by LO-TEK corresponds to Le Corbusier's "wine rack".

Freitag's shop in Zurich, 2005, takes advantage of the native stackability of containers. The company's product line of bags made from recycled truck tarps is inspired by the same ideas of recycling, found-object-art, and industrial chic that inform container architecture. Enough notable examples and practitioners of this architecture, including work by pioneers like Wes Jones and Adam Kalkin, have emerged to warrant a book-length survey, Container Architecture, by Jure Kotnik (LINKS, 2008). The movement taps into the recent explosion of interest in prefab house design, which itself signals a growing public enthusiasm for the application to housing of mass production's potential for quality control, economy, and consumer choice. This promise has always been central to the plug-in school of thought, and Le Corbusier's vision of the house as "machine for living".

Capsule in search of a host; the mass produced Loftcube, designed by Werner Aisslinger, has been helicoptered onto rooftops and hooked up to existing building services. The tiny scale of many modular house designs relates to plug-in architecture's fascination with factory made object-like dwellings, and the over-the-shoulder look that modern architecture has cast on the automobile since Le Corbusier's 1923 manifesto, Towards a New Architecture.

Capsule in search of a host; the mass produced Loftcube, designed by Werner Aisslinger, has been helicoptered onto rooftops and hooked up to existing building services. The tiny scale of many modular house designs relates to plug-in architecture's fascination with factory made object-like dwellings, and the over-the-shoulder look that modern architecture has cast on the automobile since Le Corbusier's 1923 manifesto, Towards a New Architecture.

The Adolfo Reyes 58 apartment building in Mexico City, 2000-03, by Dellekamp Arquitectos, is not modular but adopts the appearance of stacked prefab units to individually express dwellings. This variegated approach is part of a recent trend that borrows from the plug-in tradition and, in this case, the aesthetic of container architecture.

The architecture firm Axis Mundi proposed this alternative design for the MoMA tower in Manhattan earlier this month. Like Nakagin Capsule Tower, the proposal has a pair of structural/service cores. The design would allow apartment owners to customize their units' exteriors. In a nod to the origin of the new design's plug-in heritage, the stair below the Marilyn Monroe image is adopted from Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation, below. (Photo: matt2008/Flickr)

The Adolfo Reyes 58 apartment building in Mexico City, 2000-03, by Dellekamp Arquitectos, is not modular but adopts the appearance of stacked prefab units to individually express dwellings. This variegated approach is part of a recent trend that borrows from the plug-in tradition and, in this case, the aesthetic of container architecture.

The architecture firm Axis Mundi proposed this alternative design for the MoMA tower in Manhattan earlier this month. Like Nakagin Capsule Tower, the proposal has a pair of structural/service cores. The design would allow apartment owners to customize their units' exteriors. In a nod to the origin of the new design's plug-in heritage, the stair below the Marilyn Monroe image is adopted from Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation, below. (Photo: matt2008/Flickr)

Plug-in Architecture Loses an Icon

With Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower (photo: Scarletgreen/Flickr) headed for demolition, the world will lose not just one of the few executed works of Japanese Metabolism, as noted earlier this month by Nicolai Ouroussoff in the New York Times, but a rare built example of plug-in architecture. The Capsule Tower might at first appear no more than a quaint, dated vision of the future, but a look at its durable influence and vital legacy show an icon of growing historic significance whose loss will loom larger in the years to come.

With Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower (photo: Scarletgreen/Flickr) headed for demolition, the world will lose not just one of the few executed works of Japanese Metabolism, as noted earlier this month by Nicolai Ouroussoff in the New York Times, but a rare built example of plug-in architecture. The Capsule Tower might at first appear no more than a quaint, dated vision of the future, but a look at its durable influence and vital legacy show an icon of growing historic significance whose loss will loom larger in the years to come.

A tower of plug-in "capsule" homes was designed by Archigram's Warren Chalk in 1964. Inspired by space capsules, Chalk's prefabricated dwelling modules would plug into a central shaft providing structural support, vertical circulation and services. Capsule living units would be replaced by a top-mounted crane as newer models evolved, using automobiles as an analogy. Of Archigram's concepts, this one most closely corresponds to any of the few Japanese Metabolist projects actually to be built, Nakagin Capsule Tower.

A tower of plug-in "capsule" homes was designed by Archigram's Warren Chalk in 1964. Inspired by space capsules, Chalk's prefabricated dwelling modules would plug into a central shaft providing structural support, vertical circulation and services. Capsule living units would be replaced by a top-mounted crane as newer models evolved, using automobiles as an analogy. Of Archigram's concepts, this one most closely corresponds to any of the few Japanese Metabolist projects actually to be built, Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Cranes of the Port Newark Container Terminal loom beyond a Bayonne, New Jersey, trailer park. Off the architectural high road, trailer parks have long implemented the ideal of mass produced dwelling units plugged into a fixed infrastructure. Trailers take the concept a step further by allowing homes to easily relocate from one infrastructure to another. On a separate real-world track, shipping container technology, with its industrialized capsules constantly rearranged by cranes, parallels the ideas of Archigram.

The firm LO-TEK, in its multiple Modular Dwelling Unit proposal of 2002, applies container technology to the mobile home precedent by way of a vertical support framework that would realize Le Corbusier's wine rack analogy, with shipping containers retrofitted into homes serving as the bottles. LOT-EK's concept includes drawer-like "subvolumes" that pull out from each container's body, admitting natural light and creating activity areas larger than the containers' 8-foot width. The vertical frames, or "harbors" include stairs, elevators and services. Harbors would be located in all major metropolitan areas to maximize mobility. The sustainability of this system begins with repurposing of containers and continues with mobility of dwellings. The naturally varied appearance of recycled containers corresponds to Corbusier's use of different colors on the exterior of the Unite d'Habitations to identify individual dwelling units. Or as LO-TEK puts it, “The vertical harbor is in constant transformation as MDUs are loaded and unloaded from the permanent rack. Like pixels in a digital image, temporary patterns are generated by the presence or absence of MDUs in different locations along the rack, reflecting the ever-changing composition of these colonies scattered around the globe.” While many real projects, including a hotel, have taken advantage of containers' stackable-by-design character, LOT-EK's use of a separate frame would allow true plug-in flexibility.

Echoing Archigram's Plug-in City, the cranes endemic to container yards would insert or withdraw living capsules. The fixed frame proposed by LO-TEK corresponds to Le Corbusier's "wine rack".

Freitag's shop in Zurich, 2005, takes advantage of the native stackability of containers. The company's product line of bags made from recycled truck tarps is inspired by the same ideas of recycling, found-object-art, and industrial chic that inform container architecture. Enough notable examples and practitioners of this architecture, including work by pioneers like Wes Jones and Adam Kalkin, have emerged to warrant a book-length survey, Container Architecture, by Jure Kotnik (LINKS, 2008). The movement taps into the recent explosion of interest in prefab house design, which itself signals a growing public enthusiasm for the application to housing of mass production's potential for quality control, economy, and consumer choice. This promise has always been central to the plug-in school of thought, and Le Corbusier's vision of the house as "machine for living".

Cranes of the Port Newark Container Terminal loom beyond a Bayonne, New Jersey, trailer park. Off the architectural high road, trailer parks have long implemented the ideal of mass produced dwelling units plugged into a fixed infrastructure. Trailers take the concept a step further by allowing homes to easily relocate from one infrastructure to another. On a separate real-world track, shipping container technology, with its industrialized capsules constantly rearranged by cranes, parallels the ideas of Archigram.

The firm LO-TEK, in its multiple Modular Dwelling Unit proposal of 2002, applies container technology to the mobile home precedent by way of a vertical support framework that would realize Le Corbusier's wine rack analogy, with shipping containers retrofitted into homes serving as the bottles. LOT-EK's concept includes drawer-like "subvolumes" that pull out from each container's body, admitting natural light and creating activity areas larger than the containers' 8-foot width. The vertical frames, or "harbors" include stairs, elevators and services. Harbors would be located in all major metropolitan areas to maximize mobility. The sustainability of this system begins with repurposing of containers and continues with mobility of dwellings. The naturally varied appearance of recycled containers corresponds to Corbusier's use of different colors on the exterior of the Unite d'Habitations to identify individual dwelling units. Or as LO-TEK puts it, “The vertical harbor is in constant transformation as MDUs are loaded and unloaded from the permanent rack. Like pixels in a digital image, temporary patterns are generated by the presence or absence of MDUs in different locations along the rack, reflecting the ever-changing composition of these colonies scattered around the globe.” While many real projects, including a hotel, have taken advantage of containers' stackable-by-design character, LOT-EK's use of a separate frame would allow true plug-in flexibility.

Echoing Archigram's Plug-in City, the cranes endemic to container yards would insert or withdraw living capsules. The fixed frame proposed by LO-TEK corresponds to Le Corbusier's "wine rack".

Freitag's shop in Zurich, 2005, takes advantage of the native stackability of containers. The company's product line of bags made from recycled truck tarps is inspired by the same ideas of recycling, found-object-art, and industrial chic that inform container architecture. Enough notable examples and practitioners of this architecture, including work by pioneers like Wes Jones and Adam Kalkin, have emerged to warrant a book-length survey, Container Architecture, by Jure Kotnik (LINKS, 2008). The movement taps into the recent explosion of interest in prefab house design, which itself signals a growing public enthusiasm for the application to housing of mass production's potential for quality control, economy, and consumer choice. This promise has always been central to the plug-in school of thought, and Le Corbusier's vision of the house as "machine for living".

Capsule in search of a host; the mass produced Loftcube, designed by Werner Aisslinger, has been helicoptered onto rooftops and hooked up to existing building services. The tiny scale of many modular house designs relates to plug-in architecture's fascination with factory made object-like dwellings, and the over-the-shoulder look that modern architecture has cast on the automobile since Le Corbusier's 1923 manifesto, Towards a New Architecture.

Capsule in search of a host; the mass produced Loftcube, designed by Werner Aisslinger, has been helicoptered onto rooftops and hooked up to existing building services. The tiny scale of many modular house designs relates to plug-in architecture's fascination with factory made object-like dwellings, and the over-the-shoulder look that modern architecture has cast on the automobile since Le Corbusier's 1923 manifesto, Towards a New Architecture.

The Adolfo Reyes 58 apartment building in Mexico City, 2000-03, by Dellekamp Arquitectos, is not modular but adopts the appearance of stacked prefab units to individually express dwellings. This variegated approach is part of a recent trend that borrows from the plug-in tradition and, in this case, the aesthetic of container architecture.

The architecture firm Axis Mundi proposed this alternative design for the MoMA tower in Manhattan earlier this month. Like Nakagin Capsule Tower, the proposal has a pair of structural/service cores. The design would allow apartment owners to customize their units' exteriors. In a nod to the origin of the new design's plug-in heritage, the stair below the Marilyn Monroe image is adopted from Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation, below. (Photo: matt2008/Flickr)

The Adolfo Reyes 58 apartment building in Mexico City, 2000-03, by Dellekamp Arquitectos, is not modular but adopts the appearance of stacked prefab units to individually express dwellings. This variegated approach is part of a recent trend that borrows from the plug-in tradition and, in this case, the aesthetic of container architecture.

The architecture firm Axis Mundi proposed this alternative design for the MoMA tower in Manhattan earlier this month. Like Nakagin Capsule Tower, the proposal has a pair of structural/service cores. The design would allow apartment owners to customize their units' exteriors. In a nod to the origin of the new design's plug-in heritage, the stair below the Marilyn Monroe image is adopted from Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation, below. (Photo: matt2008/Flickr)

Is World's New Largest Building the Spawn of Manhattan's Muni?

Is World's New Largest Building the Spawn of Manhattan's Muni?