House Rules

House Rule 5 - Engage the Outdoors

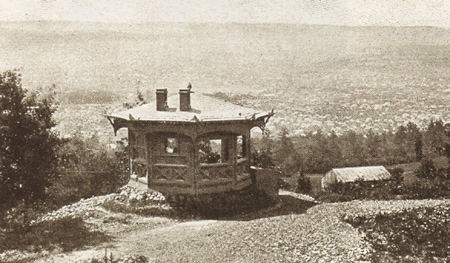

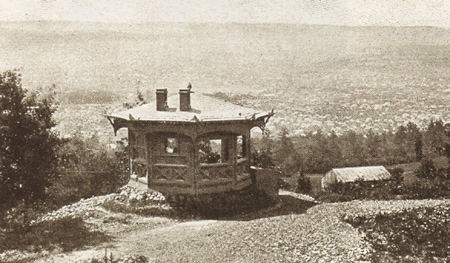

An illustration from William A. Bruette's 1934 book, Log Camps & Cabins, shows an example of a cabin open at one end like a cave. Outside, a campfire extends the domestic realm into nature. The composition is the barest refinement of primitive man's cave with banked fire outside. The book's epigraph reads: "The cabin in the forest, on the banks of a quiet lake or buried in the wilderness back of beyond, is an expression of man's desire to escape the exactions of civilization and secure rest and seclusion by a return to the primitive." Or in Huck Finn's words, "The Widow Douglas she took me for her son, and allowed she would sivilize me; but it was rough living in the house all the time, considering how dismal regular and decent the widow was in all her ways; and so when I couldn't stand it no longer I lit out. I got into my old rags and my sugar-hogshead again, and was free and satisfied." Few humans would prefer any kind of architecture to the pleasure and freedom of being outdoors in comfortable weather. Even without retreating "back of beyond," houses can make the most of their devil's bargain between shelter and space.

An illustration from William A. Bruette's 1934 book, Log Camps & Cabins, shows an example of a cabin open at one end like a cave. Outside, a campfire extends the domestic realm into nature. The composition is the barest refinement of primitive man's cave with banked fire outside. The book's epigraph reads: "The cabin in the forest, on the banks of a quiet lake or buried in the wilderness back of beyond, is an expression of man's desire to escape the exactions of civilization and secure rest and seclusion by a return to the primitive." Or in Huck Finn's words, "The Widow Douglas she took me for her son, and allowed she would sivilize me; but it was rough living in the house all the time, considering how dismal regular and decent the widow was in all her ways; and so when I couldn't stand it no longer I lit out. I got into my old rags and my sugar-hogshead again, and was free and satisfied." Few humans would prefer any kind of architecture to the pleasure and freedom of being outdoors in comfortable weather. Even without retreating "back of beyond," houses can make the most of their devil's bargain between shelter and space.

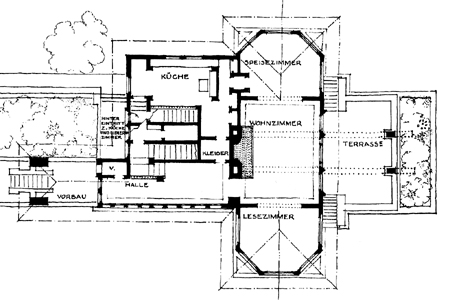

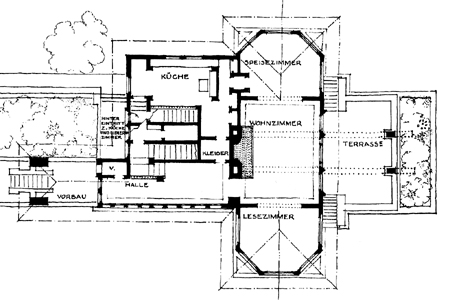

The plan of Frank Lloyd Wright's 1901 Henderson House is a near mirror-image of his Hickox House of 1900 (see House Rule 2) and very similar to his proposal for "A Home in a Prairie Town," published in the Ladies Home Journal in 1901. Each of these combines living functions into a single long but articulated space; dining area and library on either side of a living room with hearth. In each house, the living room spills out onto a terrace that matches its width and axial relationship to the hearth; living room and terrace can be read as a single space incidentally divided by French doors. In the drawing above, the living room's ceiling beams - shown in dashed lines - extend through the exterior wall and over the open terrace, further claiming its outdoor space as an extension of the interior.

The plan of Frank Lloyd Wright's 1901 Henderson House is a near mirror-image of his Hickox House of 1900 (see House Rule 2) and very similar to his proposal for "A Home in a Prairie Town," published in the Ladies Home Journal in 1901. Each of these combines living functions into a single long but articulated space; dining area and library on either side of a living room with hearth. In each house, the living room spills out onto a terrace that matches its width and axial relationship to the hearth; living room and terrace can be read as a single space incidentally divided by French doors. In the drawing above, the living room's ceiling beams - shown in dashed lines - extend through the exterior wall and over the open terrace, further claiming its outdoor space as an extension of the interior.

Wright's 1905 Darwin Martin House Complex weaves together indoor and outdoor space. The main house is a more complex development of the Hickox and Henderson House plans Wright had earlier seen fit to repeat. Their terraces are here replaced by a covered porch, the floor of which is finished in the same one-inch square floor tiles as the living area. Above and below, the porch is a more committed relationship of interior to exterior. A crescent of planting gives the porch privacy and defines an extended domain for the established grouping of library, living and dining room.

The enclosed space of Mies van der Rohe's 1929 Barcelona Pavilion projects itself into open air by the suggestive effects of continuous flooring, interpenetrating walls and an overhanging roof. Mies acknowledged Wright's impact from the time of the 1910 German Wasmuth Portfolio of his work.

Graham Phillips' 2001 Skywood House adapts the exterior-claiming strategies of the Barcelona Pavilion to a home. Pushing the limits of minimalism, it comes full circle to the image of a cave facing a clearing.

Graham Phillips' 2001 Skywood House adapts the exterior-claiming strategies of the Barcelona Pavilion to a home. Pushing the limits of minimalism, it comes full circle to the image of a cave facing a clearing.

A drawing detail of Sir Edward Brantwood Maufe's 1912 Kelling Hall shows a wing ending in a concave wall that seems to draw in outdoor space. Maufe reverses the usual projecting bow-window in favor of an implied exterior room, blurring the transition from enclosed interior space to nature. The primitive cave and its threshold are refined into a cut-stone concavity and terrace.

A drawing detail of Sir Edward Brantwood Maufe's 1912 Kelling Hall shows a wing ending in a concave wall that seems to draw in outdoor space. Maufe reverses the usual projecting bow-window in favor of an implied exterior room, blurring the transition from enclosed interior space to nature. The primitive cave and its threshold are refined into a cut-stone concavity and terrace.

Future Systems' cave-like 1998 House in Wales is bermed into the ground at the top of a cliff. It looks out over the sea through an elliptical wall of glass, like an eye. Describing it, Jan Kaplicky of Future Systems said: "There is only the grass and the glass. Nothing else, no architecture."

Future Systems' cave-like 1998 House in Wales is bermed into the ground at the top of a cliff. It looks out over the sea through an elliptical wall of glass, like an eye. Describing it, Jan Kaplicky of Future Systems said: "There is only the grass and the glass. Nothing else, no architecture."

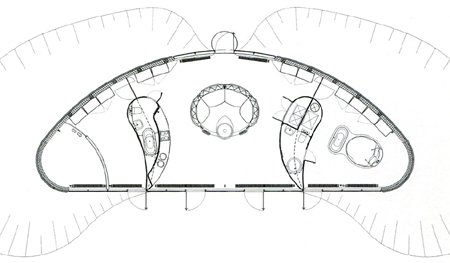

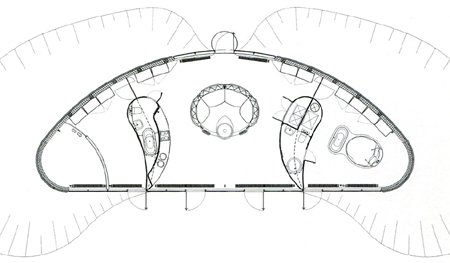

The floor plan of the House in Wales shows earth mounded up on either side and around the back, except for a narrow gap for the main entry door, centered on the curved rear wall. The earth falls away more broadly at the straight section of wall, which is entirely glass where exposed, allowing an expansive view over the sea. At the center of the house, a curved sofa focuses on a suspended fireplace, re-enacting the campfire circle of our cave-dwelling forebears and heightening the design's contrast of primitive to futuristic. Symmetrical teardrop-shaped cores contain bathrooms, utilities and the kitchen counter. Their shape creates both a fluid transition between rooms and a sense of space expanding into nature. The curved back wall embraces the vista, drawing the outdoors into the greater circle it implies. Without any exterior effort to claim outdoor space, the house is made entirely one with it, and infinitely amplified.

The floor plan of the House in Wales shows earth mounded up on either side and around the back, except for a narrow gap for the main entry door, centered on the curved rear wall. The earth falls away more broadly at the straight section of wall, which is entirely glass where exposed, allowing an expansive view over the sea. At the center of the house, a curved sofa focuses on a suspended fireplace, re-enacting the campfire circle of our cave-dwelling forebears and heightening the design's contrast of primitive to futuristic. Symmetrical teardrop-shaped cores contain bathrooms, utilities and the kitchen counter. Their shape creates both a fluid transition between rooms and a sense of space expanding into nature. The curved back wall embraces the vista, drawing the outdoors into the greater circle it implies. Without any exterior effort to claim outdoor space, the house is made entirely one with it, and infinitely amplified.

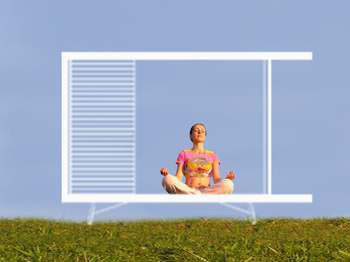

Tezuka Architects' 2005 Floating Roof House has banks of sliding doors on either side. When they are fully retracted, the interior becomes an open-air pavilion protected only by a narrow roof. Rather than spilling out to the exterior, the interior is itself transformed into outdoors. The strategy, a hallmark of Tezuka's work, was pioneered by Mies van der Rohe in his 1930 Tugendhat House, with its glazed living room wall that disappears down a slot into the basement.

Tezuka Architects' 2005 Floating Roof House has banks of sliding doors on either side. When they are fully retracted, the interior becomes an open-air pavilion protected only by a narrow roof. Rather than spilling out to the exterior, the interior is itself transformed into outdoors. The strategy, a hallmark of Tezuka's work, was pioneered by Mies van der Rohe in his 1930 Tugendhat House, with its glazed living room wall that disappears down a slot into the basement.

Barton Myers' 1999 House and Studio at Toro Canyon makes interior convertible to exterior with walls of glazed garage doors. The house is a high-design response to the impulse of American suburbanites who in warm weather relax on lawn chairs in their garages, the door drawn up overhead, sipping beer from cans and paying unconscious homage to the threshold-dwelling ambivalence of our caveman forebears.

Rule 5 is to engage the outdoors.

Barton Myers' 1999 House and Studio at Toro Canyon makes interior convertible to exterior with walls of glazed garage doors. The house is a high-design response to the impulse of American suburbanites who in warm weather relax on lawn chairs in their garages, the door drawn up overhead, sipping beer from cans and paying unconscious homage to the threshold-dwelling ambivalence of our caveman forebears.

Rule 5 is to engage the outdoors.

Conceive of the living space of a house as part of a greater whole that includes exterior space. Minimize the barrier between the indoor and outdoor components of this whole and unite them with a common material, breadth or boundary, or by inflecting the inside of the house to address its surroundings. The interior will gain a sense of release, its perceived boundary expanding into the outdoors.

House Rule 5 - Engage the Outdoors

An illustration from William A. Bruette's 1934 book, Log Camps & Cabins, shows an example of a cabin open at one end like a cave. Outside, a campfire extends the domestic realm into nature. The composition is the barest refinement of primitive man's cave with banked fire outside. The book's epigraph reads: "The cabin in the forest, on the banks of a quiet lake or buried in the wilderness back of beyond, is an expression of man's desire to escape the exactions of civilization and secure rest and seclusion by a return to the primitive." Or in Huck Finn's words, "The Widow Douglas she took me for her son, and allowed she would sivilize me; but it was rough living in the house all the time, considering how dismal regular and decent the widow was in all her ways; and so when I couldn't stand it no longer I lit out. I got into my old rags and my sugar-hogshead again, and was free and satisfied." Few humans would prefer any kind of architecture to the pleasure and freedom of being outdoors in comfortable weather. Even without retreating "back of beyond," houses can make the most of their devil's bargain between shelter and space.

An illustration from William A. Bruette's 1934 book, Log Camps & Cabins, shows an example of a cabin open at one end like a cave. Outside, a campfire extends the domestic realm into nature. The composition is the barest refinement of primitive man's cave with banked fire outside. The book's epigraph reads: "The cabin in the forest, on the banks of a quiet lake or buried in the wilderness back of beyond, is an expression of man's desire to escape the exactions of civilization and secure rest and seclusion by a return to the primitive." Or in Huck Finn's words, "The Widow Douglas she took me for her son, and allowed she would sivilize me; but it was rough living in the house all the time, considering how dismal regular and decent the widow was in all her ways; and so when I couldn't stand it no longer I lit out. I got into my old rags and my sugar-hogshead again, and was free and satisfied." Few humans would prefer any kind of architecture to the pleasure and freedom of being outdoors in comfortable weather. Even without retreating "back of beyond," houses can make the most of their devil's bargain between shelter and space.

The plan of Frank Lloyd Wright's 1901 Henderson House is a near mirror-image of his Hickox House of 1900 (see House Rule 2) and very similar to his proposal for "A Home in a Prairie Town," published in the Ladies Home Journal in 1901. Each of these combines living functions into a single long but articulated space; dining area and library on either side of a living room with hearth. In each house, the living room spills out onto a terrace that matches its width and axial relationship to the hearth; living room and terrace can be read as a single space incidentally divided by French doors. In the drawing above, the living room's ceiling beams - shown in dashed lines - extend through the exterior wall and over the open terrace, further claiming its outdoor space as an extension of the interior.

The plan of Frank Lloyd Wright's 1901 Henderson House is a near mirror-image of his Hickox House of 1900 (see House Rule 2) and very similar to his proposal for "A Home in a Prairie Town," published in the Ladies Home Journal in 1901. Each of these combines living functions into a single long but articulated space; dining area and library on either side of a living room with hearth. In each house, the living room spills out onto a terrace that matches its width and axial relationship to the hearth; living room and terrace can be read as a single space incidentally divided by French doors. In the drawing above, the living room's ceiling beams - shown in dashed lines - extend through the exterior wall and over the open terrace, further claiming its outdoor space as an extension of the interior.

Wright's 1905 Darwin Martin House Complex weaves together indoor and outdoor space. The main house is a more complex development of the Hickox and Henderson House plans Wright had earlier seen fit to repeat. Their terraces are here replaced by a covered porch, the floor of which is finished in the same one-inch square floor tiles as the living area. Above and below, the porch is a more committed relationship of interior to exterior. A crescent of planting gives the porch privacy and defines an extended domain for the established grouping of library, living and dining room.

The enclosed space of Mies van der Rohe's 1929 Barcelona Pavilion projects itself into open air by the suggestive effects of continuous flooring, interpenetrating walls and an overhanging roof. Mies acknowledged Wright's impact from the time of the 1910 German Wasmuth Portfolio of his work.

Graham Phillips' 2001 Skywood House adapts the exterior-claiming strategies of the Barcelona Pavilion to a home. Pushing the limits of minimalism, it comes full circle to the image of a cave facing a clearing.

Graham Phillips' 2001 Skywood House adapts the exterior-claiming strategies of the Barcelona Pavilion to a home. Pushing the limits of minimalism, it comes full circle to the image of a cave facing a clearing.

A drawing detail of Sir Edward Brantwood Maufe's 1912 Kelling Hall shows a wing ending in a concave wall that seems to draw in outdoor space. Maufe reverses the usual projecting bow-window in favor of an implied exterior room, blurring the transition from enclosed interior space to nature. The primitive cave and its threshold are refined into a cut-stone concavity and terrace.

A drawing detail of Sir Edward Brantwood Maufe's 1912 Kelling Hall shows a wing ending in a concave wall that seems to draw in outdoor space. Maufe reverses the usual projecting bow-window in favor of an implied exterior room, blurring the transition from enclosed interior space to nature. The primitive cave and its threshold are refined into a cut-stone concavity and terrace.

Future Systems' cave-like 1998 House in Wales is bermed into the ground at the top of a cliff. It looks out over the sea through an elliptical wall of glass, like an eye. Describing it, Jan Kaplicky of Future Systems said: "There is only the grass and the glass. Nothing else, no architecture."

Future Systems' cave-like 1998 House in Wales is bermed into the ground at the top of a cliff. It looks out over the sea through an elliptical wall of glass, like an eye. Describing it, Jan Kaplicky of Future Systems said: "There is only the grass and the glass. Nothing else, no architecture."

The floor plan of the House in Wales shows earth mounded up on either side and around the back, except for a narrow gap for the main entry door, centered on the curved rear wall. The earth falls away more broadly at the straight section of wall, which is entirely glass where exposed, allowing an expansive view over the sea. At the center of the house, a curved sofa focuses on a suspended fireplace, re-enacting the campfire circle of our cave-dwelling forebears and heightening the design's contrast of primitive to futuristic. Symmetrical teardrop-shaped cores contain bathrooms, utilities and the kitchen counter. Their shape creates both a fluid transition between rooms and a sense of space expanding into nature. The curved back wall embraces the vista, drawing the outdoors into the greater circle it implies. Without any exterior effort to claim outdoor space, the house is made entirely one with it, and infinitely amplified.

The floor plan of the House in Wales shows earth mounded up on either side and around the back, except for a narrow gap for the main entry door, centered on the curved rear wall. The earth falls away more broadly at the straight section of wall, which is entirely glass where exposed, allowing an expansive view over the sea. At the center of the house, a curved sofa focuses on a suspended fireplace, re-enacting the campfire circle of our cave-dwelling forebears and heightening the design's contrast of primitive to futuristic. Symmetrical teardrop-shaped cores contain bathrooms, utilities and the kitchen counter. Their shape creates both a fluid transition between rooms and a sense of space expanding into nature. The curved back wall embraces the vista, drawing the outdoors into the greater circle it implies. Without any exterior effort to claim outdoor space, the house is made entirely one with it, and infinitely amplified.

Tezuka Architects' 2005 Floating Roof House has banks of sliding doors on either side. When they are fully retracted, the interior becomes an open-air pavilion protected only by a narrow roof. Rather than spilling out to the exterior, the interior is itself transformed into outdoors. The strategy, a hallmark of Tezuka's work, was pioneered by Mies van der Rohe in his 1930 Tugendhat House, with its glazed living room wall that disappears down a slot into the basement.

Tezuka Architects' 2005 Floating Roof House has banks of sliding doors on either side. When they are fully retracted, the interior becomes an open-air pavilion protected only by a narrow roof. Rather than spilling out to the exterior, the interior is itself transformed into outdoors. The strategy, a hallmark of Tezuka's work, was pioneered by Mies van der Rohe in his 1930 Tugendhat House, with its glazed living room wall that disappears down a slot into the basement.

Barton Myers' 1999 House and Studio at Toro Canyon makes interior convertible to exterior with walls of glazed garage doors. The house is a high-design response to the impulse of American suburbanites who in warm weather relax on lawn chairs in their garages, the door drawn up overhead, sipping beer from cans and paying unconscious homage to the threshold-dwelling ambivalence of our caveman forebears.

Rule 5 is to engage the outdoors.

Barton Myers' 1999 House and Studio at Toro Canyon makes interior convertible to exterior with walls of glazed garage doors. The house is a high-design response to the impulse of American suburbanites who in warm weather relax on lawn chairs in their garages, the door drawn up overhead, sipping beer from cans and paying unconscious homage to the threshold-dwelling ambivalence of our caveman forebears.

Rule 5 is to engage the outdoors.

Conceive of the living space of a house as part of a greater whole that includes exterior space. Minimize the barrier between the indoor and outdoor components of this whole and unite them with a common material, breadth or boundary, or by inflecting the inside of the house to address its surroundings. The interior will gain a sense of release, its perceived boundary expanding into the outdoors.

House Rule 4 - Pursue a One-Room Ideal

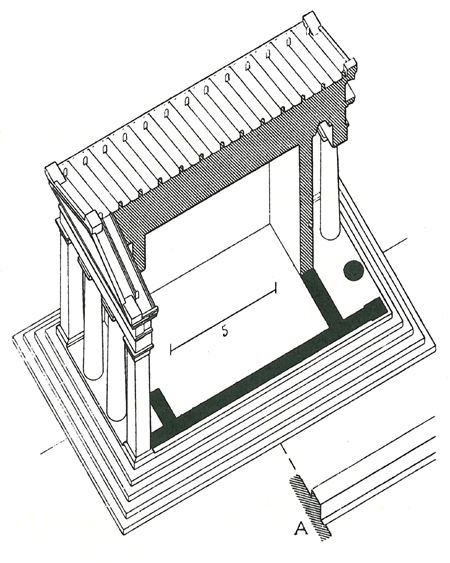

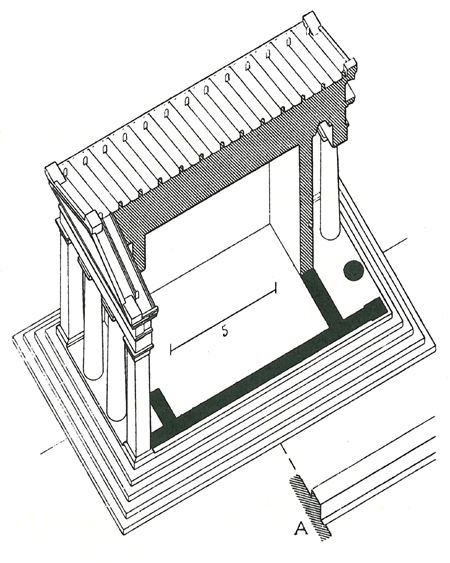

A cutaway drawing of the Temple of Diana Propylaea at Eleusis illustrates Auguste Choisy's 1899 Histoire de L'Architecture. From tepees to temples to iconic mid-century glass houses, one-room buildings derive a primitive power from their simple integration of interior and exterior.

A cutaway drawing of the Temple of Diana Propylaea at Eleusis illustrates Auguste Choisy's 1899 Histoire de L'Architecture. From tepees to temples to iconic mid-century glass houses, one-room buildings derive a primitive power from their simple integration of interior and exterior.

Frank Gehry's Winton Guest House of 1983-86 is a maximalist response to the call of the one-room building, with each of its several rooms a building unto itself. Gehry said of his work from the period, "I thought that by minimizing the issue of function, by creating one-room buildings, we could resolve the most difficult problems in architecture. Think of the power of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings ever built are one-room buildings." Gehry's approach exceeds the budget of the typical American family, but his appreciation of one-room power is universally applicable. For those who would tap into it, there are minimalist prototypes that suggest how to put multiple functions into what feels like a one-room house.

Frank Gehry's Winton Guest House of 1983-86 is a maximalist response to the call of the one-room building, with each of its several rooms a building unto itself. Gehry said of his work from the period, "I thought that by minimizing the issue of function, by creating one-room buildings, we could resolve the most difficult problems in architecture. Think of the power of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings ever built are one-room buildings." Gehry's approach exceeds the budget of the typical American family, but his appreciation of one-room power is universally applicable. For those who would tap into it, there are minimalist prototypes that suggest how to put multiple functions into what feels like a one-room house.

The plan of Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House of 1945-51 is shown above that of Philip Johnson's Glass House of 1945-49. Johnson said: "The idea of a glass house comes from Mies van der Rohe. Mies had mentioned to me as early as 1945 how easy it would be to to build a house entirely of large sheets of glass. . . . I pointed out to him that it was impossible because you had to have rooms, and that meant solid walls up against the glass, which ruined the whole point; Mies said, ‘I think it can be done’.” Mies's solution was to eliminate partitions and create a one-room house. In doing so, he didn't just find a way to make a pristine enclosure, but satisfied an inherited human impulse. Arthur Drexler referred to this when he wrote that "Mies' most original buildings are one-story structures, and the greatest of these consist of one room. In this sense Mies has designed nothing but temples, which is to say that he has revealed the irrational mainspring of our technological culture." It's no wonder that when Philip Johnson followed Mies's lead, he found the requisite unpartitioned interior "less a defect than a boon," according to his biographer, Franz Schulze. Both houses in fact have more than one room, but disguise service spaces as freestanding objects. The success of this strategy proves that there are effective ways to give a house of multiple spaces the sense of one room.

The plan of Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House of 1945-51 is shown above that of Philip Johnson's Glass House of 1945-49. Johnson said: "The idea of a glass house comes from Mies van der Rohe. Mies had mentioned to me as early as 1945 how easy it would be to to build a house entirely of large sheets of glass. . . . I pointed out to him that it was impossible because you had to have rooms, and that meant solid walls up against the glass, which ruined the whole point; Mies said, ‘I think it can be done’.” Mies's solution was to eliminate partitions and create a one-room house. In doing so, he didn't just find a way to make a pristine enclosure, but satisfied an inherited human impulse. Arthur Drexler referred to this when he wrote that "Mies' most original buildings are one-story structures, and the greatest of these consist of one room. In this sense Mies has designed nothing but temples, which is to say that he has revealed the irrational mainspring of our technological culture." It's no wonder that when Philip Johnson followed Mies's lead, he found the requisite unpartitioned interior "less a defect than a boon," according to his biographer, Franz Schulze. Both houses in fact have more than one room, but disguise service spaces as freestanding objects. The success of this strategy proves that there are effective ways to give a house of multiple spaces the sense of one room.

A floor plan of Comlongon Castle, a 15th century Scottish tower house, shows subsidiary rooms and a stair contained within the thick walls of a single central room. The main room is so dominant, clearly defined and undisturbed by its surrounding support spaces that the castle retains the sense of a one room building. Louis I. Kahn saw in it a way to provide services without compromising the integrity of primary spaces. He wrote: "The Scottish Castle. Thick, thick walls. Little openings to the enemy. Splayed inwardly to the occupant. A place to read, a place to sew. . . . Places for the bed, for the stair. . . . Sunlight. Fairy tale." This inspiration is most literally applied in the thickened wall that contains services in his Esherick House, illustrated in Rule 3.

A floor plan of Comlongon Castle, a 15th century Scottish tower house, shows subsidiary rooms and a stair contained within the thick walls of a single central room. The main room is so dominant, clearly defined and undisturbed by its surrounding support spaces that the castle retains the sense of a one room building. Louis I. Kahn saw in it a way to provide services without compromising the integrity of primary spaces. He wrote: "The Scottish Castle. Thick, thick walls. Little openings to the enemy. Splayed inwardly to the occupant. A place to read, a place to sew. . . . Places for the bed, for the stair. . . . Sunlight. Fairy tale." This inspiration is most literally applied in the thickened wall that contains services in his Esherick House, illustrated in Rule 3.

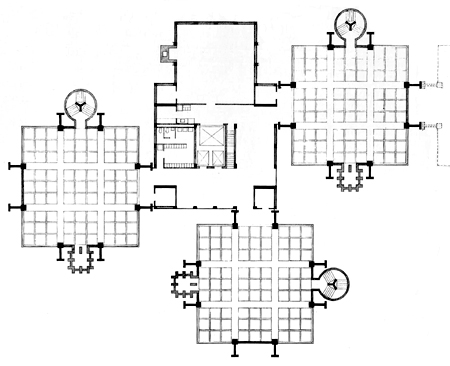

An early version floor plan of Kahn's 1957-61 Richards Medical Center at the University of Pennsylvania shows three square laboratory spaces clustered around a central service core. Like the central room at Comlongon Castle, each laboratory is a pure shape surrounded by support functions - stair, ventilation shaft and columns - clearly illustrating Kahn's idea of an architecture of served and servant spaces. As at the castle, these would be stacked into towers.

An early version floor plan of Kahn's 1957-61 Richards Medical Center at the University of Pennsylvania shows three square laboratory spaces clustered around a central service core. Like the central room at Comlongon Castle, each laboratory is a pure shape surrounded by support functions - stair, ventilation shaft and columns - clearly illustrating Kahn's idea of an architecture of served and servant spaces. As at the castle, these would be stacked into towers.

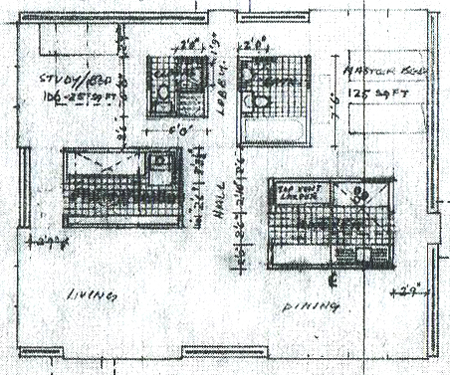

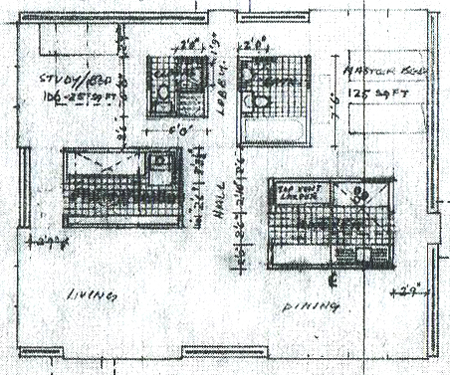

A sketch of Alison and Peter Smithson's 1959 "Retirement House" project for Alison's parents owes a clear debt to the Richards Medical Research building by Kahn. Here the surrounding "servant" appendages are bathroom, kitchen and storage and the central "served" space is a one-room house.

A sketch of Alison and Peter Smithson's 1959 "Retirement House" project for Alison's parents owes a clear debt to the Richards Medical Research building by Kahn. Here the surrounding "servant" appendages are bathroom, kitchen and storage and the central "served" space is a one-room house.

A more developed plan of the Smithson's Retirement House turns the earlier version inside out, bringing Kahn's servant spaces indoors as multiple offspring of the Farnsworth House core. These are held away from the exterior walls, even though a glass perimeter isn't at issue here. The inviolate perimeter does, however, create much the same one-room effect as the Farnsworth House, with a simple shell enclosing a single flowing space. A sense of freedom and endlessness is produced by the absence of dead ends or space-trapping corners; even the necessary inside angles of the outer box are each glazed on one side, suggesting continuation of interior space to the exterior, and flooding what would otherwise be dark corners with light. The loose arrangement of the service cores creates separate areas for different functions which flow into each other, rather than the usual bento box of contained rooms.

A more developed plan of the Smithson's Retirement House turns the earlier version inside out, bringing Kahn's servant spaces indoors as multiple offspring of the Farnsworth House core. These are held away from the exterior walls, even though a glass perimeter isn't at issue here. The inviolate perimeter does, however, create much the same one-room effect as the Farnsworth House, with a simple shell enclosing a single flowing space. A sense of freedom and endlessness is produced by the absence of dead ends or space-trapping corners; even the necessary inside angles of the outer box are each glazed on one side, suggesting continuation of interior space to the exterior, and flooding what would otherwise be dark corners with light. The loose arrangement of the service cores creates separate areas for different functions which flow into each other, rather than the usual bento box of contained rooms.

Benthem Crouwel's Benthem House is a high-tech, lightweight update on the one-room house. Its services occupy a thickened wall in the manner of Kahn. The strip of cabana-like rooms at right contains kitchen, bath, mechanical equipment and two small bedrooms. What the house gives up in the 360 degree outlook of its Farnsworth House ancestor, it makes up in livability. The opaque service bar of such a solution might also provide privacy on a less remote and more affordable site than the Farnsworth House's.

Benthem Crouwel's Benthem House is a high-tech, lightweight update on the one-room house. Its services occupy a thickened wall in the manner of Kahn. The strip of cabana-like rooms at right contains kitchen, bath, mechanical equipment and two small bedrooms. What the house gives up in the 360 degree outlook of its Farnsworth House ancestor, it makes up in livability. The opaque service bar of such a solution might also provide privacy on a less remote and more affordable site than the Farnsworth House's.

Thomas Phifer's Salt Point House, completed in 2007, has an island service core on its first floor that creates privacy between its entry area, at right, and living area, at left. The plan adopts the Farnsworth House's model of a single room with a freestanding core, but affords privacy in a way that might be useful to any house on a narrow lot.

Thomas Phifer's Salt Point House, completed in 2007, has an island service core on its first floor that creates privacy between its entry area, at right, and living area, at left. The plan adopts the Farnsworth House's model of a single room with a freestanding core, but affords privacy in a way that might be useful to any house on a narrow lot.

Pierre Koenig's Bailey House of 1958-60, also known as Case Study House #21, uses both island-core and thickened-wall strategies. The upper rectangle shows the house's enclosed envelope, framed by opaque walls on each side and encircled by a moat that is occasionally bridged by brick-paved patios. The living space is at left. Its gridded floor encircles a core of two bathrooms flanking a tiny open-roofed court. This claims the space all around the core as part of the living area, extending its domain right up to the bedroom and offiice at the extreme right. These are defined not by partitions but only a change in flooring, and might be read as part of a thickened wall even though they are spatially open to the gridded floor associated with the living area. They can be sealed off from each other by sliding doors, and from the living functions by pocket doors on either end of the bathroom core, aligned with the house's centerline. Closing these can convert the entire right half of the house into a thickened wall containing private support spaces. With this design, Koenig takes Mies's ideal of the one-room house into impressively practical territory. By day, with its sliding doors open, the house can feel nearly as open as the Farnsworth House, all its spaces contributing to a building-sized expanse. What might be constrained corridors in another architect's hands here contribute to the house's open area. By night, its more private spaces have the option of being closed off. The house was designed for a childless couple but might serve a small family as well, thanks to its easy flexibility. The study is immediately convertible to a bedroom but meanwhile has a welcome openness not usually found in a spare bedroom. The Bailey House is an open and flexible model particularly well scaled to the typical American family of today.

House Rule 4 is to pursue a one-room ideal.

Pierre Koenig's Bailey House of 1958-60, also known as Case Study House #21, uses both island-core and thickened-wall strategies. The upper rectangle shows the house's enclosed envelope, framed by opaque walls on each side and encircled by a moat that is occasionally bridged by brick-paved patios. The living space is at left. Its gridded floor encircles a core of two bathrooms flanking a tiny open-roofed court. This claims the space all around the core as part of the living area, extending its domain right up to the bedroom and offiice at the extreme right. These are defined not by partitions but only a change in flooring, and might be read as part of a thickened wall even though they are spatially open to the gridded floor associated with the living area. They can be sealed off from each other by sliding doors, and from the living functions by pocket doors on either end of the bathroom core, aligned with the house's centerline. Closing these can convert the entire right half of the house into a thickened wall containing private support spaces. With this design, Koenig takes Mies's ideal of the one-room house into impressively practical territory. By day, with its sliding doors open, the house can feel nearly as open as the Farnsworth House, all its spaces contributing to a building-sized expanse. What might be constrained corridors in another architect's hands here contribute to the house's open area. By night, its more private spaces have the option of being closed off. The house was designed for a childless couple but might serve a small family as well, thanks to its easy flexibility. The study is immediately convertible to a bedroom but meanwhile has a welcome openness not usually found in a spare bedroom. The Bailey House is an open and flexible model particularly well scaled to the typical American family of today.

House Rule 4 is to pursue a one-room ideal.

![]() Pursue the clarity and simplicity of a one-room house. Give priority to a single continuous interior space, and treat services that must be enclosed, like bathrooms, closets and utility rooms, either as islands within this space or as part of thickened exterior walls enclosing it. Minimize dead ends, interior corners and containment in favor of a sense of uninterrupted space.

Continue to House Rule 5

Pursue the clarity and simplicity of a one-room house. Give priority to a single continuous interior space, and treat services that must be enclosed, like bathrooms, closets and utility rooms, either as islands within this space or as part of thickened exterior walls enclosing it. Minimize dead ends, interior corners and containment in favor of a sense of uninterrupted space.

Continue to House Rule 5

House Rule 4 - Pursue a One-Room Ideal

A cutaway drawing of the Temple of Diana Propylaea at Eleusis illustrates Auguste Choisy's 1899 Histoire de L'Architecture. From tepees to temples to iconic mid-century glass houses, one-room buildings derive a primitive power from their simple integration of interior and exterior.

A cutaway drawing of the Temple of Diana Propylaea at Eleusis illustrates Auguste Choisy's 1899 Histoire de L'Architecture. From tepees to temples to iconic mid-century glass houses, one-room buildings derive a primitive power from their simple integration of interior and exterior.

Frank Gehry's Winton Guest House of 1983-86 is a maximalist response to the call of the one-room building, with each of its several rooms a building unto itself. Gehry said of his work from the period, "I thought that by minimizing the issue of function, by creating one-room buildings, we could resolve the most difficult problems in architecture. Think of the power of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings ever built are one-room buildings." Gehry's approach exceeds the budget of the typical American family, but his appreciation of one-room power is universally applicable. For those who would tap into it, there are minimalist prototypes that suggest how to put multiple functions into what feels like a one-room house.

Frank Gehry's Winton Guest House of 1983-86 is a maximalist response to the call of the one-room building, with each of its several rooms a building unto itself. Gehry said of his work from the period, "I thought that by minimizing the issue of function, by creating one-room buildings, we could resolve the most difficult problems in architecture. Think of the power of one-room buildings and the fact that historically, the best buildings ever built are one-room buildings." Gehry's approach exceeds the budget of the typical American family, but his appreciation of one-room power is universally applicable. For those who would tap into it, there are minimalist prototypes that suggest how to put multiple functions into what feels like a one-room house.

The plan of Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House of 1945-51 is shown above that of Philip Johnson's Glass House of 1945-49. Johnson said: "The idea of a glass house comes from Mies van der Rohe. Mies had mentioned to me as early as 1945 how easy it would be to to build a house entirely of large sheets of glass. . . . I pointed out to him that it was impossible because you had to have rooms, and that meant solid walls up against the glass, which ruined the whole point; Mies said, ‘I think it can be done’.” Mies's solution was to eliminate partitions and create a one-room house. In doing so, he didn't just find a way to make a pristine enclosure, but satisfied an inherited human impulse. Arthur Drexler referred to this when he wrote that "Mies' most original buildings are one-story structures, and the greatest of these consist of one room. In this sense Mies has designed nothing but temples, which is to say that he has revealed the irrational mainspring of our technological culture." It's no wonder that when Philip Johnson followed Mies's lead, he found the requisite unpartitioned interior "less a defect than a boon," according to his biographer, Franz Schulze. Both houses in fact have more than one room, but disguise service spaces as freestanding objects. The success of this strategy proves that there are effective ways to give a house of multiple spaces the sense of one room.

The plan of Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House of 1945-51 is shown above that of Philip Johnson's Glass House of 1945-49. Johnson said: "The idea of a glass house comes from Mies van der Rohe. Mies had mentioned to me as early as 1945 how easy it would be to to build a house entirely of large sheets of glass. . . . I pointed out to him that it was impossible because you had to have rooms, and that meant solid walls up against the glass, which ruined the whole point; Mies said, ‘I think it can be done’.” Mies's solution was to eliminate partitions and create a one-room house. In doing so, he didn't just find a way to make a pristine enclosure, but satisfied an inherited human impulse. Arthur Drexler referred to this when he wrote that "Mies' most original buildings are one-story structures, and the greatest of these consist of one room. In this sense Mies has designed nothing but temples, which is to say that he has revealed the irrational mainspring of our technological culture." It's no wonder that when Philip Johnson followed Mies's lead, he found the requisite unpartitioned interior "less a defect than a boon," according to his biographer, Franz Schulze. Both houses in fact have more than one room, but disguise service spaces as freestanding objects. The success of this strategy proves that there are effective ways to give a house of multiple spaces the sense of one room.

A floor plan of Comlongon Castle, a 15th century Scottish tower house, shows subsidiary rooms and a stair contained within the thick walls of a single central room. The main room is so dominant, clearly defined and undisturbed by its surrounding support spaces that the castle retains the sense of a one room building. Louis I. Kahn saw in it a way to provide services without compromising the integrity of primary spaces. He wrote: "The Scottish Castle. Thick, thick walls. Little openings to the enemy. Splayed inwardly to the occupant. A place to read, a place to sew. . . . Places for the bed, for the stair. . . . Sunlight. Fairy tale." This inspiration is most literally applied in the thickened wall that contains services in his Esherick House, illustrated in Rule 3.

A floor plan of Comlongon Castle, a 15th century Scottish tower house, shows subsidiary rooms and a stair contained within the thick walls of a single central room. The main room is so dominant, clearly defined and undisturbed by its surrounding support spaces that the castle retains the sense of a one room building. Louis I. Kahn saw in it a way to provide services without compromising the integrity of primary spaces. He wrote: "The Scottish Castle. Thick, thick walls. Little openings to the enemy. Splayed inwardly to the occupant. A place to read, a place to sew. . . . Places for the bed, for the stair. . . . Sunlight. Fairy tale." This inspiration is most literally applied in the thickened wall that contains services in his Esherick House, illustrated in Rule 3.

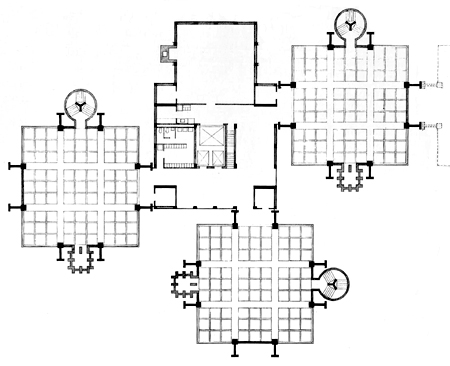

An early version floor plan of Kahn's 1957-61 Richards Medical Center at the University of Pennsylvania shows three square laboratory spaces clustered around a central service core. Like the central room at Comlongon Castle, each laboratory is a pure shape surrounded by support functions - stair, ventilation shaft and columns - clearly illustrating Kahn's idea of an architecture of served and servant spaces. As at the castle, these would be stacked into towers.

An early version floor plan of Kahn's 1957-61 Richards Medical Center at the University of Pennsylvania shows three square laboratory spaces clustered around a central service core. Like the central room at Comlongon Castle, each laboratory is a pure shape surrounded by support functions - stair, ventilation shaft and columns - clearly illustrating Kahn's idea of an architecture of served and servant spaces. As at the castle, these would be stacked into towers.

A sketch of Alison and Peter Smithson's 1959 "Retirement House" project for Alison's parents owes a clear debt to the Richards Medical Research building by Kahn. Here the surrounding "servant" appendages are bathroom, kitchen and storage and the central "served" space is a one-room house.

A sketch of Alison and Peter Smithson's 1959 "Retirement House" project for Alison's parents owes a clear debt to the Richards Medical Research building by Kahn. Here the surrounding "servant" appendages are bathroom, kitchen and storage and the central "served" space is a one-room house.

A more developed plan of the Smithson's Retirement House turns the earlier version inside out, bringing Kahn's servant spaces indoors as multiple offspring of the Farnsworth House core. These are held away from the exterior walls, even though a glass perimeter isn't at issue here. The inviolate perimeter does, however, create much the same one-room effect as the Farnsworth House, with a simple shell enclosing a single flowing space. A sense of freedom and endlessness is produced by the absence of dead ends or space-trapping corners; even the necessary inside angles of the outer box are each glazed on one side, suggesting continuation of interior space to the exterior, and flooding what would otherwise be dark corners with light. The loose arrangement of the service cores creates separate areas for different functions which flow into each other, rather than the usual bento box of contained rooms.

A more developed plan of the Smithson's Retirement House turns the earlier version inside out, bringing Kahn's servant spaces indoors as multiple offspring of the Farnsworth House core. These are held away from the exterior walls, even though a glass perimeter isn't at issue here. The inviolate perimeter does, however, create much the same one-room effect as the Farnsworth House, with a simple shell enclosing a single flowing space. A sense of freedom and endlessness is produced by the absence of dead ends or space-trapping corners; even the necessary inside angles of the outer box are each glazed on one side, suggesting continuation of interior space to the exterior, and flooding what would otherwise be dark corners with light. The loose arrangement of the service cores creates separate areas for different functions which flow into each other, rather than the usual bento box of contained rooms.

Benthem Crouwel's Benthem House is a high-tech, lightweight update on the one-room house. Its services occupy a thickened wall in the manner of Kahn. The strip of cabana-like rooms at right contains kitchen, bath, mechanical equipment and two small bedrooms. What the house gives up in the 360 degree outlook of its Farnsworth House ancestor, it makes up in livability. The opaque service bar of such a solution might also provide privacy on a less remote and more affordable site than the Farnsworth House's.

Benthem Crouwel's Benthem House is a high-tech, lightweight update on the one-room house. Its services occupy a thickened wall in the manner of Kahn. The strip of cabana-like rooms at right contains kitchen, bath, mechanical equipment and two small bedrooms. What the house gives up in the 360 degree outlook of its Farnsworth House ancestor, it makes up in livability. The opaque service bar of such a solution might also provide privacy on a less remote and more affordable site than the Farnsworth House's.

Thomas Phifer's Salt Point House, completed in 2007, has an island service core on its first floor that creates privacy between its entry area, at right, and living area, at left. The plan adopts the Farnsworth House's model of a single room with a freestanding core, but affords privacy in a way that might be useful to any house on a narrow lot.

Thomas Phifer's Salt Point House, completed in 2007, has an island service core on its first floor that creates privacy between its entry area, at right, and living area, at left. The plan adopts the Farnsworth House's model of a single room with a freestanding core, but affords privacy in a way that might be useful to any house on a narrow lot.

Pierre Koenig's Bailey House of 1958-60, also known as Case Study House #21, uses both island-core and thickened-wall strategies. The upper rectangle shows the house's enclosed envelope, framed by opaque walls on each side and encircled by a moat that is occasionally bridged by brick-paved patios. The living space is at left. Its gridded floor encircles a core of two bathrooms flanking a tiny open-roofed court. This claims the space all around the core as part of the living area, extending its domain right up to the bedroom and offiice at the extreme right. These are defined not by partitions but only a change in flooring, and might be read as part of a thickened wall even though they are spatially open to the gridded floor associated with the living area. They can be sealed off from each other by sliding doors, and from the living functions by pocket doors on either end of the bathroom core, aligned with the house's centerline. Closing these can convert the entire right half of the house into a thickened wall containing private support spaces. With this design, Koenig takes Mies's ideal of the one-room house into impressively practical territory. By day, with its sliding doors open, the house can feel nearly as open as the Farnsworth House, all its spaces contributing to a building-sized expanse. What might be constrained corridors in another architect's hands here contribute to the house's open area. By night, its more private spaces have the option of being closed off. The house was designed for a childless couple but might serve a small family as well, thanks to its easy flexibility. The study is immediately convertible to a bedroom but meanwhile has a welcome openness not usually found in a spare bedroom. The Bailey House is an open and flexible model particularly well scaled to the typical American family of today.

House Rule 4 is to pursue a one-room ideal.

Pierre Koenig's Bailey House of 1958-60, also known as Case Study House #21, uses both island-core and thickened-wall strategies. The upper rectangle shows the house's enclosed envelope, framed by opaque walls on each side and encircled by a moat that is occasionally bridged by brick-paved patios. The living space is at left. Its gridded floor encircles a core of two bathrooms flanking a tiny open-roofed court. This claims the space all around the core as part of the living area, extending its domain right up to the bedroom and offiice at the extreme right. These are defined not by partitions but only a change in flooring, and might be read as part of a thickened wall even though they are spatially open to the gridded floor associated with the living area. They can be sealed off from each other by sliding doors, and from the living functions by pocket doors on either end of the bathroom core, aligned with the house's centerline. Closing these can convert the entire right half of the house into a thickened wall containing private support spaces. With this design, Koenig takes Mies's ideal of the one-room house into impressively practical territory. By day, with its sliding doors open, the house can feel nearly as open as the Farnsworth House, all its spaces contributing to a building-sized expanse. What might be constrained corridors in another architect's hands here contribute to the house's open area. By night, its more private spaces have the option of being closed off. The house was designed for a childless couple but might serve a small family as well, thanks to its easy flexibility. The study is immediately convertible to a bedroom but meanwhile has a welcome openness not usually found in a spare bedroom. The Bailey House is an open and flexible model particularly well scaled to the typical American family of today.

House Rule 4 is to pursue a one-room ideal.

![]() Pursue the clarity and simplicity of a one-room house. Give priority to a single continuous interior space, and treat services that must be enclosed, like bathrooms, closets and utility rooms, either as islands within this space or as part of thickened exterior walls enclosing it. Minimize dead ends, interior corners and containment in favor of a sense of uninterrupted space.

Continue to House Rule 5

Pursue the clarity and simplicity of a one-room house. Give priority to a single continuous interior space, and treat services that must be enclosed, like bathrooms, closets and utility rooms, either as islands within this space or as part of thickened exterior walls enclosing it. Minimize dead ends, interior corners and containment in favor of a sense of uninterrupted space.

Continue to House Rule 5

House Rule 3 - Design from a Diagram

"A Lake or River Villa for a Picturesque Site" illustrates A.J. Downing's 1850 book, The Architecture of Country Houses. Its orderly cruciform plan of perfectly shaped rooms is undisturbed by the messy supporting business of kitchen, laundry and storage hidden out back. Unprepared for the encroachment of modern equipment, the villa's designer simply tacks on a perfunctory service wing that drifts off the page while he focuses on the familiar building blocks of room and stair. Today's house designer has even more services to integrate, with bathrooms, wrap-around kitchens, utility rooms and attached garages. He seems just as ill prepared to integrate these, and often puts up a dummy house-front of formal rooms to simplify composition of the street façade and to serve as an uninhabited buffer zone shielding the private family spaces and their services in back. As with Downing's example, the rear face of today's house is a secondary concern. The accidental backs to be glimpsed across rear yards of housing tracts attest to this. Modern house-plan fare visibly strains to juggle curb appeal, integrity of rooms, and integrated services. Downing's example drops the ball on incorporation of services in favor of whole rooms and a picturesque face.

"A Lake or River Villa for a Picturesque Site" illustrates A.J. Downing's 1850 book, The Architecture of Country Houses. Its orderly cruciform plan of perfectly shaped rooms is undisturbed by the messy supporting business of kitchen, laundry and storage hidden out back. Unprepared for the encroachment of modern equipment, the villa's designer simply tacks on a perfunctory service wing that drifts off the page while he focuses on the familiar building blocks of room and stair. Today's house designer has even more services to integrate, with bathrooms, wrap-around kitchens, utility rooms and attached garages. He seems just as ill prepared to integrate these, and often puts up a dummy house-front of formal rooms to simplify composition of the street façade and to serve as an uninhabited buffer zone shielding the private family spaces and their services in back. As with Downing's example, the rear face of today's house is a secondary concern. The accidental backs to be glimpsed across rear yards of housing tracts attest to this. Modern house-plan fare visibly strains to juggle curb appeal, integrity of rooms, and integrated services. Downing's example drops the ball on incorporation of services in favor of whole rooms and a picturesque face.

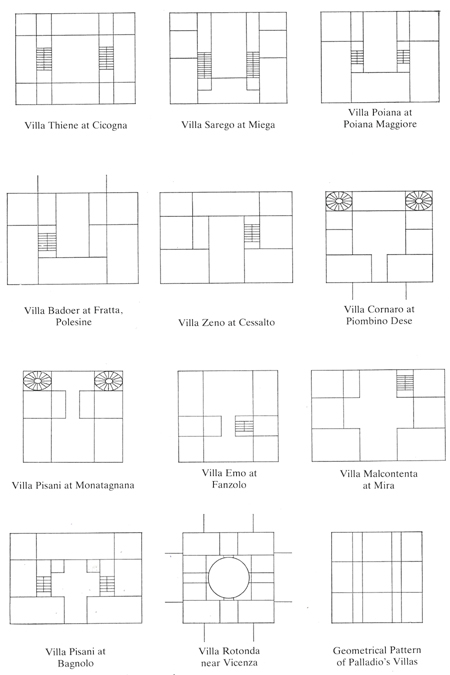

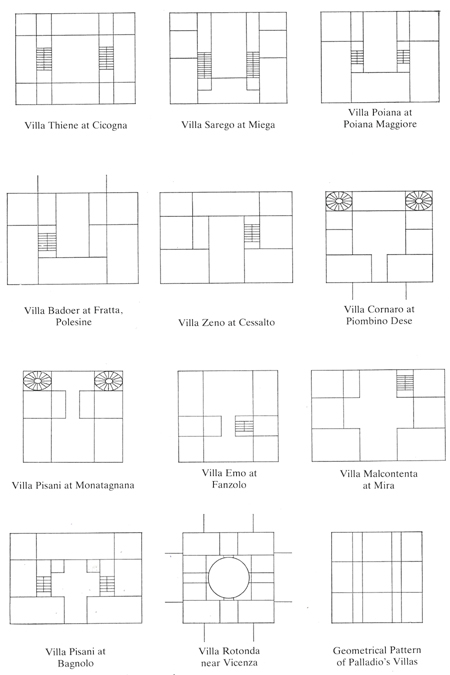

Rudolph Wittkower's influential 1949 book, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, is illustrated with "Schematized plans of eleven of Palladio's Villas." Wittkower identifies the grid pattern at lower right as the basis for all of these. By stretching its zones slightly and selectively omitting line segments, Palladio used this diagram to define all of a villa's spaces at once. The simultaneity and comprehensiveness of this method allowed rooms of varying shapes, sizes and orientations to mesh perfectly within a simple container. The approach contrasts with that of the designer who plants rooms sequentially across a house, one decision limiting the next, and each additional room more awkwardly forced into whatever space remains. This hapless approach is evident in the gerrymandered outline of the combined living spaces in so many of today's houses, shapes no one would ever intentionally set out to make but could only have backed into.

Rudolph Wittkower's influential 1949 book, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, is illustrated with "Schematized plans of eleven of Palladio's Villas." Wittkower identifies the grid pattern at lower right as the basis for all of these. By stretching its zones slightly and selectively omitting line segments, Palladio used this diagram to define all of a villa's spaces at once. The simultaneity and comprehensiveness of this method allowed rooms of varying shapes, sizes and orientations to mesh perfectly within a simple container. The approach contrasts with that of the designer who plants rooms sequentially across a house, one decision limiting the next, and each additional room more awkwardly forced into whatever space remains. This hapless approach is evident in the gerrymandered outline of the combined living spaces in so many of today's houses, shapes no one would ever intentionally set out to make but could only have backed into.

Wittkower's pattern is here overlaid on Palladio's Villa Foscari, "La Malcontenta," of 1558-60. Working from this pattern, Palladio not only insured perfectly formed rooms that would fit together with the precision of puzzle pieces, but pre-loaded the building faces with a classical rhythm. As the walls were all load-bearing, the pattern also automatically gave his villas a workable system of structural bays. The vaulted ceiling at the center of La Malcontenta illustrates his method's marriage of structure and form. The pattern's "tartan" alternation of wide and narrow zones would be adopted by later architects to integrate modern services, as foreshadowed by its unintrusive accommodation of stairs in Palladio's villas.

Wittkower's pattern is here overlaid on Palladio's Villa Foscari, "La Malcontenta," of 1558-60. Working from this pattern, Palladio not only insured perfectly formed rooms that would fit together with the precision of puzzle pieces, but pre-loaded the building faces with a classical rhythm. As the walls were all load-bearing, the pattern also automatically gave his villas a workable system of structural bays. The vaulted ceiling at the center of La Malcontenta illustrates his method's marriage of structure and form. The pattern's "tartan" alternation of wide and narrow zones would be adopted by later architects to integrate modern services, as foreshadowed by its unintrusive accommodation of stairs in Palladio's villas.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 1894 Winslow House compactly internalizes services like kitchen and pantry (upper left), stairs, driveway entrance and storage without compromising the shape or organization of its living spaces.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 1894 Winslow House compactly internalizes services like kitchen and pantry (upper left), stairs, driveway entrance and storage without compromising the shape or organization of its living spaces.

Above, Palladio's grid pattern is laid over the Winslow House plan, demonstrating its adaptability to the machine age. A geometric pattern allowed Wright to absorb services into a coherent plan. While most often recognized as history's most influential architect for his classical vocabulary, Palladio's way with order has extended his impact into modern architecture.

Above, Palladio's grid pattern is laid over the Winslow House plan, demonstrating its adaptability to the machine age. A geometric pattern allowed Wright to absorb services into a coherent plan. While most often recognized as history's most influential architect for his classical vocabulary, Palladio's way with order has extended his impact into modern architecture.

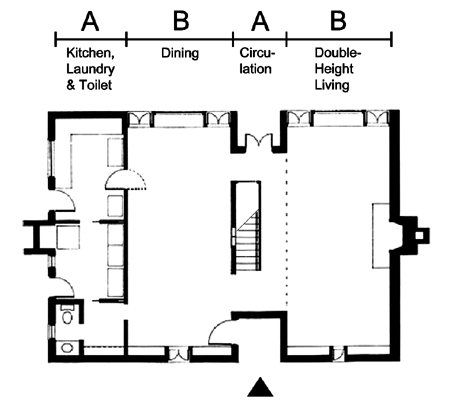

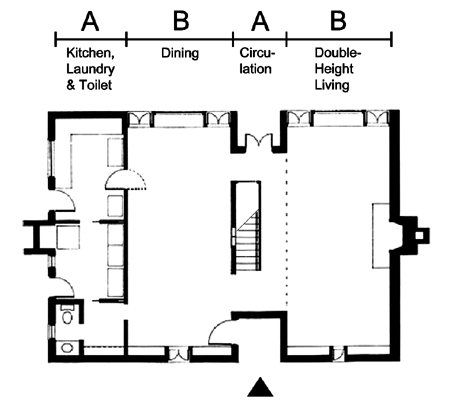

Louis Kahn's 1959-61 Esherick House applies a simple abab rhythm of narrow (service) and wide (living) zones to a one-bedroom house for a single woman. Kahn was fascinated by Wittkower's illustration of Palladio's villa pattern, which contributed to his conception of buildings composed of served and servant spaces. He saw in the narrow bands of the tartan grid an opportunity to assimilate a building's smaller support functions without disrupting its primary spaces or overall order. The Esherick House echos the wide-narrow-wide pattern of the traditional center-hall house but adds another narrow zone on one side, containing the modern service machinery of kitchen, toilet and laundry downstairs and the master bath and closets upstairs. This zone is effectively a closed but permeable "servant" block placed functionally between the driveway and the open "served" living space, the upper and lower levels of which are united by a double-height living room. Sliding partitions allow the single upstairs bedroom, above the dining room, to open onto the two-story living area, making the entire house except for the service block into a single uncomplicated space for Kahn to treat as a laboratory of natural lighting. The service block can be read as a thickened wall out of which the small support rooms have been carved, bookending the house with the nearly blank fireplace wall at its opposite end, each providing privacy from side neighbors. In its response to context, Kahn's diagram not only results in an internally coherent house, but one which is optimized to its site.

Louis Kahn's 1959-61 Esherick House applies a simple abab rhythm of narrow (service) and wide (living) zones to a one-bedroom house for a single woman. Kahn was fascinated by Wittkower's illustration of Palladio's villa pattern, which contributed to his conception of buildings composed of served and servant spaces. He saw in the narrow bands of the tartan grid an opportunity to assimilate a building's smaller support functions without disrupting its primary spaces or overall order. The Esherick House echos the wide-narrow-wide pattern of the traditional center-hall house but adds another narrow zone on one side, containing the modern service machinery of kitchen, toilet and laundry downstairs and the master bath and closets upstairs. This zone is effectively a closed but permeable "servant" block placed functionally between the driveway and the open "served" living space, the upper and lower levels of which are united by a double-height living room. Sliding partitions allow the single upstairs bedroom, above the dining room, to open onto the two-story living area, making the entire house except for the service block into a single uncomplicated space for Kahn to treat as a laboratory of natural lighting. The service block can be read as a thickened wall out of which the small support rooms have been carved, bookending the house with the nearly blank fireplace wall at its opposite end, each providing privacy from side neighbors. In its response to context, Kahn's diagram not only results in an internally coherent house, but one which is optimized to its site.

The organization of the Esherick House is legible in its rear façade. From left to right are the double-height living room, stair hall, bedroom-over-dining room, and service block.

Rule 3 is to design from a diagram.

The organization of the Esherick House is legible in its rear façade. From left to right are the double-height living room, stair hall, bedroom-over-dining room, and service block.

Rule 3 is to design from a diagram.

Design from a diagram. Begin with the spaces and functions the house must contain, and an analysis of its site. Rather than starting with individual rooms, think in terms of a few ordered zones of spaces related by size and function, and array them to exploit the site characteristics and serve an overriding design direction. A comprehensive diagram for a small house can be very simple, but will yield a purposeful design made up of simultaneously conceived spaces that are all deliberate and whole. The resulting clarity of plan will not only be economical to build, but will minimize the material and psychological clutter that a house can place between its dwellers and their simple enjoyment of life.

Continue to House Rule 4

Design from a diagram. Begin with the spaces and functions the house must contain, and an analysis of its site. Rather than starting with individual rooms, think in terms of a few ordered zones of spaces related by size and function, and array them to exploit the site characteristics and serve an overriding design direction. A comprehensive diagram for a small house can be very simple, but will yield a purposeful design made up of simultaneously conceived spaces that are all deliberate and whole. The resulting clarity of plan will not only be economical to build, but will minimize the material and psychological clutter that a house can place between its dwellers and their simple enjoyment of life.

Continue to House Rule 4

House Rule 3 - Design from a Diagram

"A Lake or River Villa for a Picturesque Site" illustrates A.J. Downing's 1850 book, The Architecture of Country Houses. Its orderly cruciform plan of perfectly shaped rooms is undisturbed by the messy supporting business of kitchen, laundry and storage hidden out back. Unprepared for the encroachment of modern equipment, the villa's designer simply tacks on a perfunctory service wing that drifts off the page while he focuses on the familiar building blocks of room and stair. Today's house designer has even more services to integrate, with bathrooms, wrap-around kitchens, utility rooms and attached garages. He seems just as ill prepared to integrate these, and often puts up a dummy house-front of formal rooms to simplify composition of the street façade and to serve as an uninhabited buffer zone shielding the private family spaces and their services in back. As with Downing's example, the rear face of today's house is a secondary concern. The accidental backs to be glimpsed across rear yards of housing tracts attest to this. Modern house-plan fare visibly strains to juggle curb appeal, integrity of rooms, and integrated services. Downing's example drops the ball on incorporation of services in favor of whole rooms and a picturesque face.

"A Lake or River Villa for a Picturesque Site" illustrates A.J. Downing's 1850 book, The Architecture of Country Houses. Its orderly cruciform plan of perfectly shaped rooms is undisturbed by the messy supporting business of kitchen, laundry and storage hidden out back. Unprepared for the encroachment of modern equipment, the villa's designer simply tacks on a perfunctory service wing that drifts off the page while he focuses on the familiar building blocks of room and stair. Today's house designer has even more services to integrate, with bathrooms, wrap-around kitchens, utility rooms and attached garages. He seems just as ill prepared to integrate these, and often puts up a dummy house-front of formal rooms to simplify composition of the street façade and to serve as an uninhabited buffer zone shielding the private family spaces and their services in back. As with Downing's example, the rear face of today's house is a secondary concern. The accidental backs to be glimpsed across rear yards of housing tracts attest to this. Modern house-plan fare visibly strains to juggle curb appeal, integrity of rooms, and integrated services. Downing's example drops the ball on incorporation of services in favor of whole rooms and a picturesque face.

Rudolph Wittkower's influential 1949 book, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, is illustrated with "Schematized plans of eleven of Palladio's Villas." Wittkower identifies the grid pattern at lower right as the basis for all of these. By stretching its zones slightly and selectively omitting line segments, Palladio used this diagram to define all of a villa's spaces at once. The simultaneity and comprehensiveness of this method allowed rooms of varying shapes, sizes and orientations to mesh perfectly within a simple container. The approach contrasts with that of the designer who plants rooms sequentially across a house, one decision limiting the next, and each additional room more awkwardly forced into whatever space remains. This hapless approach is evident in the gerrymandered outline of the combined living spaces in so many of today's houses, shapes no one would ever intentionally set out to make but could only have backed into.

Rudolph Wittkower's influential 1949 book, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, is illustrated with "Schematized plans of eleven of Palladio's Villas." Wittkower identifies the grid pattern at lower right as the basis for all of these. By stretching its zones slightly and selectively omitting line segments, Palladio used this diagram to define all of a villa's spaces at once. The simultaneity and comprehensiveness of this method allowed rooms of varying shapes, sizes and orientations to mesh perfectly within a simple container. The approach contrasts with that of the designer who plants rooms sequentially across a house, one decision limiting the next, and each additional room more awkwardly forced into whatever space remains. This hapless approach is evident in the gerrymandered outline of the combined living spaces in so many of today's houses, shapes no one would ever intentionally set out to make but could only have backed into.

Wittkower's pattern is here overlaid on Palladio's Villa Foscari, "La Malcontenta," of 1558-60. Working from this pattern, Palladio not only insured perfectly formed rooms that would fit together with the precision of puzzle pieces, but pre-loaded the building faces with a classical rhythm. As the walls were all load-bearing, the pattern also automatically gave his villas a workable system of structural bays. The vaulted ceiling at the center of La Malcontenta illustrates his method's marriage of structure and form. The pattern's "tartan" alternation of wide and narrow zones would be adopted by later architects to integrate modern services, as foreshadowed by its unintrusive accommodation of stairs in Palladio's villas.

Wittkower's pattern is here overlaid on Palladio's Villa Foscari, "La Malcontenta," of 1558-60. Working from this pattern, Palladio not only insured perfectly formed rooms that would fit together with the precision of puzzle pieces, but pre-loaded the building faces with a classical rhythm. As the walls were all load-bearing, the pattern also automatically gave his villas a workable system of structural bays. The vaulted ceiling at the center of La Malcontenta illustrates his method's marriage of structure and form. The pattern's "tartan" alternation of wide and narrow zones would be adopted by later architects to integrate modern services, as foreshadowed by its unintrusive accommodation of stairs in Palladio's villas.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 1894 Winslow House compactly internalizes services like kitchen and pantry (upper left), stairs, driveway entrance and storage without compromising the shape or organization of its living spaces.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 1894 Winslow House compactly internalizes services like kitchen and pantry (upper left), stairs, driveway entrance and storage without compromising the shape or organization of its living spaces.

Above, Palladio's grid pattern is laid over the Winslow House plan, demonstrating its adaptability to the machine age. A geometric pattern allowed Wright to absorb services into a coherent plan. While most often recognized as history's most influential architect for his classical vocabulary, Palladio's way with order has extended his impact into modern architecture.

Above, Palladio's grid pattern is laid over the Winslow House plan, demonstrating its adaptability to the machine age. A geometric pattern allowed Wright to absorb services into a coherent plan. While most often recognized as history's most influential architect for his classical vocabulary, Palladio's way with order has extended his impact into modern architecture.

Louis Kahn's 1959-61 Esherick House applies a simple abab rhythm of narrow (service) and wide (living) zones to a one-bedroom house for a single woman. Kahn was fascinated by Wittkower's illustration of Palladio's villa pattern, which contributed to his conception of buildings composed of served and servant spaces. He saw in the narrow bands of the tartan grid an opportunity to assimilate a building's smaller support functions without disrupting its primary spaces or overall order. The Esherick House echos the wide-narrow-wide pattern of the traditional center-hall house but adds another narrow zone on one side, containing the modern service machinery of kitchen, toilet and laundry downstairs and the master bath and closets upstairs. This zone is effectively a closed but permeable "servant" block placed functionally between the driveway and the open "served" living space, the upper and lower levels of which are united by a double-height living room. Sliding partitions allow the single upstairs bedroom, above the dining room, to open onto the two-story living area, making the entire house except for the service block into a single uncomplicated space for Kahn to treat as a laboratory of natural lighting. The service block can be read as a thickened wall out of which the small support rooms have been carved, bookending the house with the nearly blank fireplace wall at its opposite end, each providing privacy from side neighbors. In its response to context, Kahn's diagram not only results in an internally coherent house, but one which is optimized to its site.

Louis Kahn's 1959-61 Esherick House applies a simple abab rhythm of narrow (service) and wide (living) zones to a one-bedroom house for a single woman. Kahn was fascinated by Wittkower's illustration of Palladio's villa pattern, which contributed to his conception of buildings composed of served and servant spaces. He saw in the narrow bands of the tartan grid an opportunity to assimilate a building's smaller support functions without disrupting its primary spaces or overall order. The Esherick House echos the wide-narrow-wide pattern of the traditional center-hall house but adds another narrow zone on one side, containing the modern service machinery of kitchen, toilet and laundry downstairs and the master bath and closets upstairs. This zone is effectively a closed but permeable "servant" block placed functionally between the driveway and the open "served" living space, the upper and lower levels of which are united by a double-height living room. Sliding partitions allow the single upstairs bedroom, above the dining room, to open onto the two-story living area, making the entire house except for the service block into a single uncomplicated space for Kahn to treat as a laboratory of natural lighting. The service block can be read as a thickened wall out of which the small support rooms have been carved, bookending the house with the nearly blank fireplace wall at its opposite end, each providing privacy from side neighbors. In its response to context, Kahn's diagram not only results in an internally coherent house, but one which is optimized to its site.

The organization of the Esherick House is legible in its rear façade. From left to right are the double-height living room, stair hall, bedroom-over-dining room, and service block.

Rule 3 is to design from a diagram.

The organization of the Esherick House is legible in its rear façade. From left to right are the double-height living room, stair hall, bedroom-over-dining room, and service block.

Rule 3 is to design from a diagram.

Design from a diagram. Begin with the spaces and functions the house must contain, and an analysis of its site. Rather than starting with individual rooms, think in terms of a few ordered zones of spaces related by size and function, and array them to exploit the site characteristics and serve an overriding design direction. A comprehensive diagram for a small house can be very simple, but will yield a purposeful design made up of simultaneously conceived spaces that are all deliberate and whole. The resulting clarity of plan will not only be economical to build, but will minimize the material and psychological clutter that a house can place between its dwellers and their simple enjoyment of life.

Continue to House Rule 4

Design from a diagram. Begin with the spaces and functions the house must contain, and an analysis of its site. Rather than starting with individual rooms, think in terms of a few ordered zones of spaces related by size and function, and array them to exploit the site characteristics and serve an overriding design direction. A comprehensive diagram for a small house can be very simple, but will yield a purposeful design made up of simultaneously conceived spaces that are all deliberate and whole. The resulting clarity of plan will not only be economical to build, but will minimize the material and psychological clutter that a house can place between its dwellers and their simple enjoyment of life.

Continue to House Rule 4

House Rule 2 - Combine Living Spaces

Frank Lloyd Wright's Hickox House of 1900 opens its dining room, living room and library onto each other, combining them into a single expansive living space that runs the full length of the house. The glazed ends of this space imply its infinite exterior projection, even as the doors leading from its center onto a terrace allow the living room to spill outside. "Vista without and vista within," were Wright's words for the effect. The outward thrust of the living space is countered by its focal hearth. Wright attuned his houses to the ingrained daily rhythm by which our forebears faced outward to hunt and gather in the landscape by day and returned to the fire at night, tapping into the primitive brain with the calculation of a movie about alien predators. In its human insight, its simultaneous appropriation of exterior space and indoor simulation of outdoor scale, and its diagrammatic clarity - pure living pavilion on one side and unintruding support functions on the other - the Hickox House is a particularly compact illustration of Wright's multilevel genius. It was a radical dwelling in its time. In his 1954 book, The Natural House, Wright described how he had broken the box of the American house a half-century earlier: