Atrocities

436 West 20th Street Rises Above the Law

White stains of efflorescence mark new brickwork at 436 West 20th Street. The gable end of the 1835 rowhouse has been raised several feet and given a gambrel profile. The original peaked roofline is clearly legible in darker-looking brick, about four feet down from the new roofline. “You have to pay attention to history,” the building's new owner and co-developer, Michael Bolla was quoted in the Daily News last month. “It tells you everything. Here history told us to spare no expense to return the house to its original form. This house has all kinds of history.” The house in fact falls within the Chelsea Historic District, and its exterior is therefore the equivalent of a designated landmark. In raising its roofline, Bolla has violated the permit his renovation was issued by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. With the raised gable end, Bolla appears to be setting the stage for a raised roof, and maximum exploitation of a penthouse he clearly views as a cash cow.

White stains of efflorescence mark new brickwork at 436 West 20th Street. The gable end of the 1835 rowhouse has been raised several feet and given a gambrel profile. The original peaked roofline is clearly legible in darker-looking brick, about four feet down from the new roofline. “You have to pay attention to history,” the building's new owner and co-developer, Michael Bolla was quoted in the Daily News last month. “It tells you everything. Here history told us to spare no expense to return the house to its original form. This house has all kinds of history.” The house in fact falls within the Chelsea Historic District, and its exterior is therefore the equivalent of a designated landmark. In raising its roofline, Bolla has violated the permit his renovation was issued by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. With the raised gable end, Bolla appears to be setting the stage for a raised roof, and maximum exploitation of a penthouse he clearly views as a cash cow.

Half of the building's lower, historic roofline still remains in this photo taken last month.

Bolla received a Certificate of Appropriateness for proposed work on 436 West 20th Street from the Landmarks Preservation Commission in December. It states the Commission's understanding "That the alterations at the roof will occur at the rear of the building, and will not be visible; that the alteration to the rear of the roof will not encompass the entire width of the roof; that the visible portion of the gable roof, and the historic roof pitch will be maintained at all sides, thereby maintaining the historic profile of the roofline, that the visible portion of the gable roof, which is a character-defining feature of the building, will retain its historic profile when viewed from the street." Despite the prominent note, "Display This Permit While Work Is In Progress," at the top of the Landmarks Permit, it has not been posted at the building during recent construction. More notably, neither has a Building Department Work Permit. A Department of Buildings Inspector responding to a complaint about this last week was "unable to gain access."

Half of the building's lower, historic roofline still remains in this photo taken last month.

Bolla received a Certificate of Appropriateness for proposed work on 436 West 20th Street from the Landmarks Preservation Commission in December. It states the Commission's understanding "That the alterations at the roof will occur at the rear of the building, and will not be visible; that the alteration to the rear of the roof will not encompass the entire width of the roof; that the visible portion of the gable roof, and the historic roof pitch will be maintained at all sides, thereby maintaining the historic profile of the roofline, that the visible portion of the gable roof, which is a character-defining feature of the building, will retain its historic profile when viewed from the street." Despite the prominent note, "Display This Permit While Work Is In Progress," at the top of the Landmarks Permit, it has not been posted at the building during recent construction. More notably, neither has a Building Department Work Permit. A Department of Buildings Inspector responding to a complaint about this last week was "unable to gain access."

Documents submitted to the Landmarks Commission for approval include a line drawing and a color rendering of the house's street face. These documents are available for the public to view at the offices of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Documents submitted to the Landmarks Commission for approval include a line drawing and a color rendering of the house's street face. These documents are available for the public to view at the offices of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

A detail of the submitted street face drawing shows only a "new roof membrane" and "new coping stone" at the roof. Drawings submitted to the Department of Buildings likewise fail to mention any increase in the height of the roof or side-wall.

A detail of the submitted street face drawing shows only a "new roof membrane" and "new coping stone" at the roof. Drawings submitted to the Department of Buildings likewise fail to mention any increase in the height of the roof or side-wall.

Now very rare in Manhattan, pitched roofs are one of the clearest indicators of a truly old building, typically dating from the early 19th century. An exemplary block of the Chelsea Historic District, on Ninth Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets, includes both pitched roofs and wood frame buildings. Such rare artifacts invaluably document New York's former self. Nothing less than the city's historical record is at stake in their accurate preservation.

Now very rare in Manhattan, pitched roofs are one of the clearest indicators of a truly old building, typically dating from the early 19th century. An exemplary block of the Chelsea Historic District, on Ninth Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets, includes both pitched roofs and wood frame buildings. Such rare artifacts invaluably document New York's former self. Nothing less than the city's historical record is at stake in their accurate preservation.

Even though #436's door surround is a relatively recent addition and not historically sensitive, Landmarks denied Bolla's proposal, evoking Donald Trump, to gild its column capitals.

In a Daily News article last month, Jason Sheftell called Bolla and his business partner Michael Daniel the "magicians" behind "one of the most perfectly restored homes in Manhattan." After noting that Bolla, who is also a realtor, "now counts Linda Evangelista, Jessica Lange, Denzel Washington and countless celebrities as clients (though he considers them more as friends)," Sheftell quotes Bolla as saying, "Everything I restore is a work of art to me. You cannot destroy what other people create, ever. It is a disgusting thing to do.” Sheftell continues, "The duplex penthouse, already rented, will have three terraces. Bolla, self-taught in design, had the 17-foot ceilings A-framed to give that floor a barn-like feel consistent with European loft homes in old city houses."

Even though #436's door surround is a relatively recent addition and not historically sensitive, Landmarks denied Bolla's proposal, evoking Donald Trump, to gild its column capitals.

In a Daily News article last month, Jason Sheftell called Bolla and his business partner Michael Daniel the "magicians" behind "one of the most perfectly restored homes in Manhattan." After noting that Bolla, who is also a realtor, "now counts Linda Evangelista, Jessica Lange, Denzel Washington and countless celebrities as clients (though he considers them more as friends)," Sheftell quotes Bolla as saying, "Everything I restore is a work of art to me. You cannot destroy what other people create, ever. It is a disgusting thing to do.” Sheftell continues, "The duplex penthouse, already rented, will have three terraces. Bolla, self-taught in design, had the 17-foot ceilings A-framed to give that floor a barn-like feel consistent with European loft homes in old city houses."

436 West 20th Street faces the park-like campus of the General Theological Seminary across a very quiet street, an exceptionally privileged situation in New York. The location's value has increased as West Chelsea's 358-strong gallery district has become what is now sometimes called, without irony, the center of the art world, and as the newly opened High Line continues to spread a wake of astronomically priced condominiums, and luxury hotels, stores and restaurants. The red brick building at right in the photo above is the newly completed Chelsea Enclave condominium. Some of its apartments have views directly onto the Seminary's lush grounds. Designed by Polshek Partnership, it earned Landmarks Commission approval within the Chelsea Historic District by virtue of a sympathetic design that, while taller than its oldest neighbors, skillfully reduces its apparent bulk to harmonize with its context. A penthouse apartment there is currently listed at $10,750,000. Bolla's construction plans for the penthouse of #436 took a more ambitious turn in recent months, and his asking rent for it recently rose from $18,000 a month to $37,500.

436 West 20th Street faces the park-like campus of the General Theological Seminary across a very quiet street, an exceptionally privileged situation in New York. The location's value has increased as West Chelsea's 358-strong gallery district has become what is now sometimes called, without irony, the center of the art world, and as the newly opened High Line continues to spread a wake of astronomically priced condominiums, and luxury hotels, stores and restaurants. The red brick building at right in the photo above is the newly completed Chelsea Enclave condominium. Some of its apartments have views directly onto the Seminary's lush grounds. Designed by Polshek Partnership, it earned Landmarks Commission approval within the Chelsea Historic District by virtue of a sympathetic design that, while taller than its oldest neighbors, skillfully reduces its apparent bulk to harmonize with its context. A penthouse apartment there is currently listed at $10,750,000. Bolla's construction plans for the penthouse of #436 took a more ambitious turn in recent months, and his asking rent for it recently rose from $18,000 a month to $37,500.

The illegal change to its roofline is only one offense on view in this photo of #436. The brick wall that has been raised is also a party wall shared with the lower rowhouse in the foreground. New window openings have been created in this wall just above the neighboring roof. The Building Code doesn't allow such windows in party walls. The larger new window, a few feet directly above the neighboring building's skylight (not to mention its entire combustible roof), is a textbook example of the flame-spread hazard that the code was written to prevent. The windows are likely intended to jack up rental revenue for the duplex penthouse space under Bolla's roof and suggest greed-over-public-good priorites. (What would Denzel say?) The Department of Buildings indicates on its online Buildings Information System that Bolla's architect, Gary Silver, first filed the project in February of 2009 as a Type 2 Alteration for "interior" work of an estimated $75,000 value. (According to Jason Sheftell's Daily News piece, "the sound insulation systems used for the floors, walls, and ceilings cost more than $500,000 alone. In total, the home cost more than $500 per square foot to rebuild." This would put the total construction cost at over $5 million.) The Building Department application form indicated that no enlargement was proposed. Over the following year, Silver filed eight amendments to this application, each claiming zero dollar value, and none having the form's "building enlargement" box checked. Some of these amendments were accompanied by revised drawings. The new party wall windows are not shown in amended drawings filed through May of last year, but suddenly appeared in amendment drawings filed in December, not proposed as new construction, but shown as existing, and thus rewritten into history. The final amendment was filed in January, still without the "Building Enlargement" box checked. However, it has drawings attached that show the rear rooftop addition. (As built, the rear extension appears to vary from these drawings by encroaching on a two-foot clear space between itself and the party wall that was called for by the Landmarks Commission and dimensioned on the Building Department drawings.) No vertical extension of the party wall was ever filed. Much of the construction to date at #436 has been done without a posted Work Permit, itself a violation.

If Bolla and Silver's filing strategy is evasive, it would just be as a precaution. Plans like theirs routinely go straight through the Building Department without passing under any official's eyes. A provision called Professional Certification, which Silver is exercising, allows architects and engineers to review their own filed drawings for code compliance in place of a Department plan examiner. "Pro Cert" relies on the integrity of state-licensed private sector professionals to uphold the law. (The Building Department audits about 20% of such projects to keep self-certifiers honest.) At the other end of the process, a provision called Directive 14 allows architects and engineers to make final inspections and sign projects off on behalf of the Building Department. Unscrupulous owners who abuse the system are at risk for fines and can be held responsible for correcting illegal conditions, but this is a very poor safety net. Once illegal construction is complete, owners can claim it was always there, or petition the Board of Standards and Appeals to leave it in place on the basis of financial hardship, or pursue after-the-fact legalization. Building without regard for the law creates facts on the ground (or in the air) that can be very hard to overturn.

The illegal change to its roofline is only one offense on view in this photo of #436. The brick wall that has been raised is also a party wall shared with the lower rowhouse in the foreground. New window openings have been created in this wall just above the neighboring roof. The Building Code doesn't allow such windows in party walls. The larger new window, a few feet directly above the neighboring building's skylight (not to mention its entire combustible roof), is a textbook example of the flame-spread hazard that the code was written to prevent. The windows are likely intended to jack up rental revenue for the duplex penthouse space under Bolla's roof and suggest greed-over-public-good priorites. (What would Denzel say?) The Department of Buildings indicates on its online Buildings Information System that Bolla's architect, Gary Silver, first filed the project in February of 2009 as a Type 2 Alteration for "interior" work of an estimated $75,000 value. (According to Jason Sheftell's Daily News piece, "the sound insulation systems used for the floors, walls, and ceilings cost more than $500,000 alone. In total, the home cost more than $500 per square foot to rebuild." This would put the total construction cost at over $5 million.) The Building Department application form indicated that no enlargement was proposed. Over the following year, Silver filed eight amendments to this application, each claiming zero dollar value, and none having the form's "building enlargement" box checked. Some of these amendments were accompanied by revised drawings. The new party wall windows are not shown in amended drawings filed through May of last year, but suddenly appeared in amendment drawings filed in December, not proposed as new construction, but shown as existing, and thus rewritten into history. The final amendment was filed in January, still without the "Building Enlargement" box checked. However, it has drawings attached that show the rear rooftop addition. (As built, the rear extension appears to vary from these drawings by encroaching on a two-foot clear space between itself and the party wall that was called for by the Landmarks Commission and dimensioned on the Building Department drawings.) No vertical extension of the party wall was ever filed. Much of the construction to date at #436 has been done without a posted Work Permit, itself a violation.

If Bolla and Silver's filing strategy is evasive, it would just be as a precaution. Plans like theirs routinely go straight through the Building Department without passing under any official's eyes. A provision called Professional Certification, which Silver is exercising, allows architects and engineers to review their own filed drawings for code compliance in place of a Department plan examiner. "Pro Cert" relies on the integrity of state-licensed private sector professionals to uphold the law. (The Building Department audits about 20% of such projects to keep self-certifiers honest.) At the other end of the process, a provision called Directive 14 allows architects and engineers to make final inspections and sign projects off on behalf of the Building Department. Unscrupulous owners who abuse the system are at risk for fines and can be held responsible for correcting illegal conditions, but this is a very poor safety net. Once illegal construction is complete, owners can claim it was always there, or petition the Board of Standards and Appeals to leave it in place on the basis of financial hardship, or pursue after-the-fact legalization. Building without regard for the law creates facts on the ground (or in the air) that can be very hard to overturn.

The deeply set-back red brick building at left, 12 West 68th Street, dates from 1925, except for its top floor, which was illegally added several years ago. While falling within the Upper West Side Historic District, the building was enlarged without approval of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. A recent change in ownership has complicated matters, with a blameless new owner trying to have the addition legalized retroactively. The turmoil surrounding this addition and the years of community effort that have gone into trying to have it removed underscore the risk of letting owners create facts in the air.

UPDATE: On April 8th, the Department of Buildings indicated on its Buildings Information System that filing for 436 West 20th Street is under audit and that a "Notice to Revoke" its work permit has been issued. More here.

More on 436 West 20th Street:

Buying Michael Bolla's Chelsea Mansion for Dummies - October 19, 2012

Where is Michael Bolla's Lawsuit? - March 1, 2011

The Seamy Side of 436 West 20th Street - October 7, 2010

Chelsea Mansion: The Art of Fiction - August 12, 2010

The deeply set-back red brick building at left, 12 West 68th Street, dates from 1925, except for its top floor, which was illegally added several years ago. While falling within the Upper West Side Historic District, the building was enlarged without approval of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. A recent change in ownership has complicated matters, with a blameless new owner trying to have the addition legalized retroactively. The turmoil surrounding this addition and the years of community effort that have gone into trying to have it removed underscore the risk of letting owners create facts in the air.

UPDATE: On April 8th, the Department of Buildings indicated on its Buildings Information System that filing for 436 West 20th Street is under audit and that a "Notice to Revoke" its work permit has been issued. More here.

More on 436 West 20th Street:

Buying Michael Bolla's Chelsea Mansion for Dummies - October 19, 2012

Where is Michael Bolla's Lawsuit? - March 1, 2011

The Seamy Side of 436 West 20th Street - October 7, 2010

Chelsea Mansion: The Art of Fiction - August 12, 2010

436 West 20th Street Rises Above the Law

White stains of efflorescence mark new brickwork at 436 West 20th Street. The gable end of the 1835 rowhouse has been raised several feet and given a gambrel profile. The original peaked roofline is clearly legible in darker-looking brick, about four feet down from the new roofline. “You have to pay attention to history,” the building's new owner and co-developer, Michael Bolla was quoted in the Daily News last month. “It tells you everything. Here history told us to spare no expense to return the house to its original form. This house has all kinds of history.” The house in fact falls within the Chelsea Historic District, and its exterior is therefore the equivalent of a designated landmark. In raising its roofline, Bolla has violated the permit his renovation was issued by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. With the raised gable end, Bolla appears to be setting the stage for a raised roof, and maximum exploitation of a penthouse he clearly views as a cash cow.

White stains of efflorescence mark new brickwork at 436 West 20th Street. The gable end of the 1835 rowhouse has been raised several feet and given a gambrel profile. The original peaked roofline is clearly legible in darker-looking brick, about four feet down from the new roofline. “You have to pay attention to history,” the building's new owner and co-developer, Michael Bolla was quoted in the Daily News last month. “It tells you everything. Here history told us to spare no expense to return the house to its original form. This house has all kinds of history.” The house in fact falls within the Chelsea Historic District, and its exterior is therefore the equivalent of a designated landmark. In raising its roofline, Bolla has violated the permit his renovation was issued by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. With the raised gable end, Bolla appears to be setting the stage for a raised roof, and maximum exploitation of a penthouse he clearly views as a cash cow.

Half of the building's lower, historic roofline still remains in this photo taken last month.

Bolla received a Certificate of Appropriateness for proposed work on 436 West 20th Street from the Landmarks Preservation Commission in December. It states the Commission's understanding "That the alterations at the roof will occur at the rear of the building, and will not be visible; that the alteration to the rear of the roof will not encompass the entire width of the roof; that the visible portion of the gable roof, and the historic roof pitch will be maintained at all sides, thereby maintaining the historic profile of the roofline, that the visible portion of the gable roof, which is a character-defining feature of the building, will retain its historic profile when viewed from the street." Despite the prominent note, "Display This Permit While Work Is In Progress," at the top of the Landmarks Permit, it has not been posted at the building during recent construction. More notably, neither has a Building Department Work Permit. A Department of Buildings Inspector responding to a complaint about this last week was "unable to gain access."

Half of the building's lower, historic roofline still remains in this photo taken last month.

Bolla received a Certificate of Appropriateness for proposed work on 436 West 20th Street from the Landmarks Preservation Commission in December. It states the Commission's understanding "That the alterations at the roof will occur at the rear of the building, and will not be visible; that the alteration to the rear of the roof will not encompass the entire width of the roof; that the visible portion of the gable roof, and the historic roof pitch will be maintained at all sides, thereby maintaining the historic profile of the roofline, that the visible portion of the gable roof, which is a character-defining feature of the building, will retain its historic profile when viewed from the street." Despite the prominent note, "Display This Permit While Work Is In Progress," at the top of the Landmarks Permit, it has not been posted at the building during recent construction. More notably, neither has a Building Department Work Permit. A Department of Buildings Inspector responding to a complaint about this last week was "unable to gain access."

Documents submitted to the Landmarks Commission for approval include a line drawing and a color rendering of the house's street face. These documents are available for the public to view at the offices of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Documents submitted to the Landmarks Commission for approval include a line drawing and a color rendering of the house's street face. These documents are available for the public to view at the offices of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

A detail of the submitted street face drawing shows only a "new roof membrane" and "new coping stone" at the roof. Drawings submitted to the Department of Buildings likewise fail to mention any increase in the height of the roof or side-wall.

A detail of the submitted street face drawing shows only a "new roof membrane" and "new coping stone" at the roof. Drawings submitted to the Department of Buildings likewise fail to mention any increase in the height of the roof or side-wall.

Now very rare in Manhattan, pitched roofs are one of the clearest indicators of a truly old building, typically dating from the early 19th century. An exemplary block of the Chelsea Historic District, on Ninth Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets, includes both pitched roofs and wood frame buildings. Such rare artifacts invaluably document New York's former self. Nothing less than the city's historical record is at stake in their accurate preservation.

Now very rare in Manhattan, pitched roofs are one of the clearest indicators of a truly old building, typically dating from the early 19th century. An exemplary block of the Chelsea Historic District, on Ninth Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets, includes both pitched roofs and wood frame buildings. Such rare artifacts invaluably document New York's former self. Nothing less than the city's historical record is at stake in their accurate preservation.

Even though #436's door surround is a relatively recent addition and not historically sensitive, Landmarks denied Bolla's proposal, evoking Donald Trump, to gild its column capitals.

In a Daily News article last month, Jason Sheftell called Bolla and his business partner Michael Daniel the "magicians" behind "one of the most perfectly restored homes in Manhattan." After noting that Bolla, who is also a realtor, "now counts Linda Evangelista, Jessica Lange, Denzel Washington and countless celebrities as clients (though he considers them more as friends)," Sheftell quotes Bolla as saying, "Everything I restore is a work of art to me. You cannot destroy what other people create, ever. It is a disgusting thing to do.” Sheftell continues, "The duplex penthouse, already rented, will have three terraces. Bolla, self-taught in design, had the 17-foot ceilings A-framed to give that floor a barn-like feel consistent with European loft homes in old city houses."

Even though #436's door surround is a relatively recent addition and not historically sensitive, Landmarks denied Bolla's proposal, evoking Donald Trump, to gild its column capitals.

In a Daily News article last month, Jason Sheftell called Bolla and his business partner Michael Daniel the "magicians" behind "one of the most perfectly restored homes in Manhattan." After noting that Bolla, who is also a realtor, "now counts Linda Evangelista, Jessica Lange, Denzel Washington and countless celebrities as clients (though he considers them more as friends)," Sheftell quotes Bolla as saying, "Everything I restore is a work of art to me. You cannot destroy what other people create, ever. It is a disgusting thing to do.” Sheftell continues, "The duplex penthouse, already rented, will have three terraces. Bolla, self-taught in design, had the 17-foot ceilings A-framed to give that floor a barn-like feel consistent with European loft homes in old city houses."

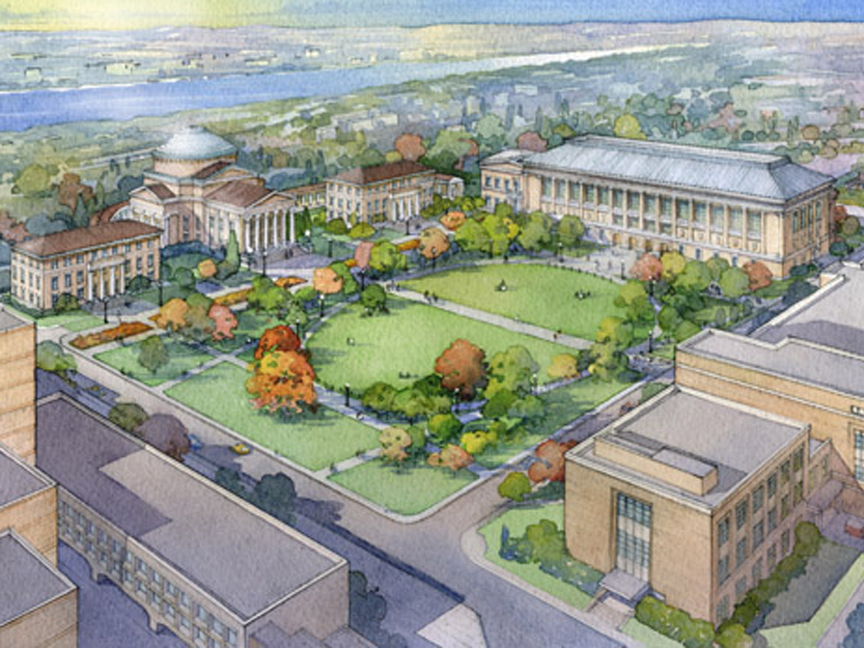

436 West 20th Street faces the park-like campus of the General Theological Seminary across a very quiet street, an exceptionally privileged situation in New York. The location's value has increased as West Chelsea's 358-strong gallery district has become what is now sometimes called, without irony, the center of the art world, and as the newly opened High Line continues to spread a wake of astronomically priced condominiums, and luxury hotels, stores and restaurants. The red brick building at right in the photo above is the newly completed Chelsea Enclave condominium. Some of its apartments have views directly onto the Seminary's lush grounds. Designed by Polshek Partnership, it earned Landmarks Commission approval within the Chelsea Historic District by virtue of a sympathetic design that, while taller than its oldest neighbors, skillfully reduces its apparent bulk to harmonize with its context. A penthouse apartment there is currently listed at $10,750,000. Bolla's construction plans for the penthouse of #436 took a more ambitious turn in recent months, and his asking rent for it recently rose from $18,000 a month to $37,500.

436 West 20th Street faces the park-like campus of the General Theological Seminary across a very quiet street, an exceptionally privileged situation in New York. The location's value has increased as West Chelsea's 358-strong gallery district has become what is now sometimes called, without irony, the center of the art world, and as the newly opened High Line continues to spread a wake of astronomically priced condominiums, and luxury hotels, stores and restaurants. The red brick building at right in the photo above is the newly completed Chelsea Enclave condominium. Some of its apartments have views directly onto the Seminary's lush grounds. Designed by Polshek Partnership, it earned Landmarks Commission approval within the Chelsea Historic District by virtue of a sympathetic design that, while taller than its oldest neighbors, skillfully reduces its apparent bulk to harmonize with its context. A penthouse apartment there is currently listed at $10,750,000. Bolla's construction plans for the penthouse of #436 took a more ambitious turn in recent months, and his asking rent for it recently rose from $18,000 a month to $37,500.

The illegal change to its roofline is only one offense on view in this photo of #436. The brick wall that has been raised is also a party wall shared with the lower rowhouse in the foreground. New window openings have been created in this wall just above the neighboring roof. The Building Code doesn't allow such windows in party walls. The larger new window, a few feet directly above the neighboring building's skylight (not to mention its entire combustible roof), is a textbook example of the flame-spread hazard that the code was written to prevent. The windows are likely intended to jack up rental revenue for the duplex penthouse space under Bolla's roof and suggest greed-over-public-good priorites. (What would Denzel say?) The Department of Buildings indicates on its online Buildings Information System that Bolla's architect, Gary Silver, first filed the project in February of 2009 as a Type 2 Alteration for "interior" work of an estimated $75,000 value. (According to Jason Sheftell's Daily News piece, "the sound insulation systems used for the floors, walls, and ceilings cost more than $500,000 alone. In total, the home cost more than $500 per square foot to rebuild." This would put the total construction cost at over $5 million.) The Building Department application form indicated that no enlargement was proposed. Over the following year, Silver filed eight amendments to this application, each claiming zero dollar value, and none having the form's "building enlargement" box checked. Some of these amendments were accompanied by revised drawings. The new party wall windows are not shown in amended drawings filed through May of last year, but suddenly appeared in amendment drawings filed in December, not proposed as new construction, but shown as existing, and thus rewritten into history. The final amendment was filed in January, still without the "Building Enlargement" box checked. However, it has drawings attached that show the rear rooftop addition. (As built, the rear extension appears to vary from these drawings by encroaching on a two-foot clear space between itself and the party wall that was called for by the Landmarks Commission and dimensioned on the Building Department drawings.) No vertical extension of the party wall was ever filed. Much of the construction to date at #436 has been done without a posted Work Permit, itself a violation.

If Bolla and Silver's filing strategy is evasive, it would just be as a precaution. Plans like theirs routinely go straight through the Building Department without passing under any official's eyes. A provision called Professional Certification, which Silver is exercising, allows architects and engineers to review their own filed drawings for code compliance in place of a Department plan examiner. "Pro Cert" relies on the integrity of state-licensed private sector professionals to uphold the law. (The Building Department audits about 20% of such projects to keep self-certifiers honest.) At the other end of the process, a provision called Directive 14 allows architects and engineers to make final inspections and sign projects off on behalf of the Building Department. Unscrupulous owners who abuse the system are at risk for fines and can be held responsible for correcting illegal conditions, but this is a very poor safety net. Once illegal construction is complete, owners can claim it was always there, or petition the Board of Standards and Appeals to leave it in place on the basis of financial hardship, or pursue after-the-fact legalization. Building without regard for the law creates facts on the ground (or in the air) that can be very hard to overturn.

The illegal change to its roofline is only one offense on view in this photo of #436. The brick wall that has been raised is also a party wall shared with the lower rowhouse in the foreground. New window openings have been created in this wall just above the neighboring roof. The Building Code doesn't allow such windows in party walls. The larger new window, a few feet directly above the neighboring building's skylight (not to mention its entire combustible roof), is a textbook example of the flame-spread hazard that the code was written to prevent. The windows are likely intended to jack up rental revenue for the duplex penthouse space under Bolla's roof and suggest greed-over-public-good priorites. (What would Denzel say?) The Department of Buildings indicates on its online Buildings Information System that Bolla's architect, Gary Silver, first filed the project in February of 2009 as a Type 2 Alteration for "interior" work of an estimated $75,000 value. (According to Jason Sheftell's Daily News piece, "the sound insulation systems used for the floors, walls, and ceilings cost more than $500,000 alone. In total, the home cost more than $500 per square foot to rebuild." This would put the total construction cost at over $5 million.) The Building Department application form indicated that no enlargement was proposed. Over the following year, Silver filed eight amendments to this application, each claiming zero dollar value, and none having the form's "building enlargement" box checked. Some of these amendments were accompanied by revised drawings. The new party wall windows are not shown in amended drawings filed through May of last year, but suddenly appeared in amendment drawings filed in December, not proposed as new construction, but shown as existing, and thus rewritten into history. The final amendment was filed in January, still without the "Building Enlargement" box checked. However, it has drawings attached that show the rear rooftop addition. (As built, the rear extension appears to vary from these drawings by encroaching on a two-foot clear space between itself and the party wall that was called for by the Landmarks Commission and dimensioned on the Building Department drawings.) No vertical extension of the party wall was ever filed. Much of the construction to date at #436 has been done without a posted Work Permit, itself a violation.

If Bolla and Silver's filing strategy is evasive, it would just be as a precaution. Plans like theirs routinely go straight through the Building Department without passing under any official's eyes. A provision called Professional Certification, which Silver is exercising, allows architects and engineers to review their own filed drawings for code compliance in place of a Department plan examiner. "Pro Cert" relies on the integrity of state-licensed private sector professionals to uphold the law. (The Building Department audits about 20% of such projects to keep self-certifiers honest.) At the other end of the process, a provision called Directive 14 allows architects and engineers to make final inspections and sign projects off on behalf of the Building Department. Unscrupulous owners who abuse the system are at risk for fines and can be held responsible for correcting illegal conditions, but this is a very poor safety net. Once illegal construction is complete, owners can claim it was always there, or petition the Board of Standards and Appeals to leave it in place on the basis of financial hardship, or pursue after-the-fact legalization. Building without regard for the law creates facts on the ground (or in the air) that can be very hard to overturn.

The deeply set-back red brick building at left, 12 West 68th Street, dates from 1925, except for its top floor, which was illegally added several years ago. While falling within the Upper West Side Historic District, the building was enlarged without approval of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. A recent change in ownership has complicated matters, with a blameless new owner trying to have the addition legalized retroactively. The turmoil surrounding this addition and the years of community effort that have gone into trying to have it removed underscore the risk of letting owners create facts in the air.

UPDATE: On April 8th, the Department of Buildings indicated on its Buildings Information System that filing for 436 West 20th Street is under audit and that a "Notice to Revoke" its work permit has been issued. More here.

More on 436 West 20th Street:

Buying Michael Bolla's Chelsea Mansion for Dummies - October 19, 2012

Where is Michael Bolla's Lawsuit? - March 1, 2011

The Seamy Side of 436 West 20th Street - October 7, 2010

Chelsea Mansion: The Art of Fiction - August 12, 2010

The deeply set-back red brick building at left, 12 West 68th Street, dates from 1925, except for its top floor, which was illegally added several years ago. While falling within the Upper West Side Historic District, the building was enlarged without approval of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. A recent change in ownership has complicated matters, with a blameless new owner trying to have the addition legalized retroactively. The turmoil surrounding this addition and the years of community effort that have gone into trying to have it removed underscore the risk of letting owners create facts in the air.

UPDATE: On April 8th, the Department of Buildings indicated on its Buildings Information System that filing for 436 West 20th Street is under audit and that a "Notice to Revoke" its work permit has been issued. More here.

More on 436 West 20th Street:

Buying Michael Bolla's Chelsea Mansion for Dummies - October 19, 2012

Where is Michael Bolla's Lawsuit? - March 1, 2011

The Seamy Side of 436 West 20th Street - October 7, 2010

Chelsea Mansion: The Art of Fiction - August 12, 2010

Robert A.M. Stern, part 2

Stern's presumptuousness may owe something to the huge attention and acclaim that attended upon 15 Central Park West, the luxury condo he designed for the Zeckendorf Brothers. Based on classic prewar apartment buildings by Rosario Candela, the project is probably the biggest real estate phenomenon New York has ever seen. Quarterly New York real estate reports had to be adjusted to factor out the distorting influence of its astronomical sales. The website Curbed took to calling it the "limestone Jesus". At a time when New York developers were finally hiring serious architects like Richard Meier and Jean Nouvel to generate appeal, 15 CPW might have been seen as the ultimate vindication for architecture's claims to create value. For architects who take their profession seriously, though, it was disappointing that what made the project so successful wasn't the kind of quality that imagination can make out of thin air, but Stern's accurate sense of what investment bankers want, and how many times over the building's limestone cladding paid for itself.

For a Vanity Fair article on 15 Central Park West, Stern posed atop its concierge desk, weakly mimicking the classic image of an urbanely macho Robert Moses poised on an I-beam over the East River. Stern shares Moses' ego, if not his public mission, a distinction emphasized by this photo's gated setting. What lies beyond is for the privileged few.

Arnold Newman's 1959 photo serves as the cover for Robert Moses and the Modern City. Moses famously said "you can't make an omelet without breaking eggs." Unlike Stern's, his omelets were for everyone's consumption. What lies beyond is a public realm.

The normally balanced architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote two glowing reviews of 15 Central Park West. His 2007 New Yorker piece, "Past Perfect", pauses just long enough to ask, is "costume-drama luxury the best that our new century has to offer?" before getting back to the building's "exquisitely crafted marble trim." His 2008 Vanity Fair review, "The King of Central Park West", is likewise awestruck save for two sentences that find the building's exterior somewhat severe and its base less articulated than those of its neighbors. Both pieces bristle with celebrity names and dollar signs. Stern's enormous output fills many 9-pound books dedicated to his bland, pretty buildings for rich people. The sheer proliferation of his easily turned-out product becomes a concern when it spreads to the public urban realm as a sort of invasive species, climbing like kudzu up the side of the Woolworth Building or choking out the native specimens of a historic New Haven neighborhood.

A chummy interview of Stern by Goldberger is included in Robert A.M. Stern: Buildings & Projects 2004-2009. Like Stern, Goldberger graduated from Yale and has taught there. Stern's career is bound up in Yale, where as a student he formed lasting relationships with faculty members Vincent Scully and Philip Johnson.

Stern helped Scully research his 1962 book on Louis I. Kahn, the first book-length study of the architect, who also taught at Yale. Scully wrote of Kahn that he "had worked himself back to a point where he could begin to design architecture afresh, literally from the ground up, accepting no preconceptions, fashions or habits of design without questioning them profoundly. That 'great event,' so rare and precious in human history, when things were about to begin anew almost as if no things had ever been before, was on the way." If Stern ever read the book he helped Scully research, it had no effect on him.

Stern's enormous output fills many 9-pound books dedicated to his bland, pretty buildings for rich people. The sheer proliferation of his easily turned-out product becomes a concern when it spreads to the public urban realm as a sort of invasive species, climbing like kudzu up the side of the Woolworth Building or choking out the native specimens of a historic New Haven neighborhood.

A chummy interview of Stern by Goldberger is included in Robert A.M. Stern: Buildings & Projects 2004-2009. Like Stern, Goldberger graduated from Yale and has taught there. Stern's career is bound up in Yale, where as a student he formed lasting relationships with faculty members Vincent Scully and Philip Johnson.

Stern helped Scully research his 1962 book on Louis I. Kahn, the first book-length study of the architect, who also taught at Yale. Scully wrote of Kahn that he "had worked himself back to a point where he could begin to design architecture afresh, literally from the ground up, accepting no preconceptions, fashions or habits of design without questioning them profoundly. That 'great event,' so rare and precious in human history, when things were about to begin anew almost as if no things had ever been before, was on the way." If Stern ever read the book he helped Scully research, it had no effect on him.

Kahn said architecture began "when the walls parted and the columns became." He preferred the bluntness of Paestum's ruins to the elegance of the Parthenon, finding them closer to the source of architecure's power. Architects like Stern see the past as something to be copied, often for easy profit, and as proof that the best that architecture has to offer is behind us. Their successive re-issues carry architecture ever farther from its generating force and original vitality.

Kahn's interest in the past is seen by some as making way for the postmodernism that Stern would pursue with such commercial success. In fact, Stern's approach to design may best be defined in contrast to Kahn's. Where Kahn finds inspiration in the past, Stern finds a crutch. Kahn's Art Gallery was the first building to break from Yale's neo-Gothic style. In 2006, Vincent Scully called the newly restored Art Gallery "our first modern building and our best." Nearly sixty years later, Stern is designing Yale's two new residential colleges in neo-Gothic style. If Stern stands for anything, it's the end of architectural history, as of the 1920s.

Kahn said architecture began "when the walls parted and the columns became." He preferred the bluntness of Paestum's ruins to the elegance of the Parthenon, finding them closer to the source of architecure's power. Architects like Stern see the past as something to be copied, often for easy profit, and as proof that the best that architecture has to offer is behind us. Their successive re-issues carry architecture ever farther from its generating force and original vitality.

Kahn's interest in the past is seen by some as making way for the postmodernism that Stern would pursue with such commercial success. In fact, Stern's approach to design may best be defined in contrast to Kahn's. Where Kahn finds inspiration in the past, Stern finds a crutch. Kahn's Art Gallery was the first building to break from Yale's neo-Gothic style. In 2006, Vincent Scully called the newly restored Art Gallery "our first modern building and our best." Nearly sixty years later, Stern is designing Yale's two new residential colleges in neo-Gothic style. If Stern stands for anything, it's the end of architectural history, as of the 1920s.

Kahn rejected the easy road of imitation and visual charm. In projects like the Salk Institute, he invested new forms with primitive power and timelessness. In a world dominated by business as usual, few opportunities exist for the creation of architecture on this level. Kahn's commitment to it accounts for his relatively small output. Yale twice gave him the opportunity to build.

In his extraordinary 2003 documentary, My Architect, Kahn's son Nathaniel searches for his father - who died in 1974 when Nathaniel was 11 - among the buildings he left and the memories of those who knew him. Interviewed for the film, Stern tries to bring Kahn down to his own level, telling Nathaniel, "Don't put him up on some gigantic pedestal. . . Don't think that he was always trying to be a prince. He was very much trying to be a player. He wanted work, he wanted recognition. . . He was success-oriented." When Nathaniel asks, "Doesn't every architect?" Stern replies, "I can't speak for every architect." Nathaniel continues in voice-over that Kahn was half a million dollars in debt when he died, and that of all his projects, only the Salk Institute made money. Kahn was known to continue developing designs well after the likelihood of their realization or his payment for them had passed. An architect who worked for Kahn, William Huff, remembers him turning down a prospective client who wanted a colonial house designed, and suggesting Thomas Jefferson when she asked him to recommend a colonial architect. In a few years, Stern would have fit her bill. Twenty-eight years ago in the Journal New Society, Reyner Banham described Stern's "complete lack of scruple that enables him to perform equally well in any style (or caricature thereof) that the market will bear."

What would Kahn make of Stern today? Of seeing Stern's status as Yale's Dean of Architecture used to hawk ten million dollar tract mansions in the sales material for Villanova Heights, the Riverdale development of Stern's 10,000 to 15,000 square foot traditionally styled luxury homes? As quoted in Carter Wiseman's 2007 book, Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, William Huff says that Kahn "saw institutions as the important entities of man's cooperative interactions," and "loved Yale, where he found greatness as an institutional awareness - more so than his own alma mater," the University of Pennsylvania. Yale gave Kahn his first and last major commissions, for its Art Gallery extension and its Museum of British Art, and can claim much of the credit for creating his career. At the end of My Architect, in Kahn's Dhaka National Assembly Building, the architect Shamsul Wares movingly tells Nathaniel Kahn what an impossible gift his father had made to the poorest country in the world, for the asking. Kahn, he says, "has given us the institution for Democracy". Yale can take some of the credit for this. It's hard to believe this great institution can't find an engaged, pluralist dean for its school of architecture who wouldn't be so venal as to trade on its name, or use it to endorse self-serving preservation offenses. Stern seems a vestige of yesterday's world of self indulgence and unsustainable consumption, of Bush era deception and arrogance. Goldberger's 15 Central Park West pieces summon up the ghost of Herbert Muschamp, who in 1988 excoriated the previous boom's architects for abandoning social responsibility to become "Satan's decorators" and "hired flunkies".

Last year, Stern published The Philip Johnson Tapes, a book collecting his 1985 interviews of his teacher and "great friend". In it, Johnson says of Kahn, "I liked his work better than I liked him. . . . I never found him the great lovely guru-type. I couldn't stand all those long monologues about belief in truth. I can't stand truth. It gets so boring, you know, like social responsibility." Stern seems a bit bored by truth himself, letting Johnson turn questions about his fascist-leaning past into opportunities for lengthy self justification and whitewashing of his personal history into that of a "violent philo-Semite." Stern doesn't even call Johnson on this unreconstructed view of Germany in the 1930s: "I mean, Germany was being run down by the rich. The German Workers Party was the only solution. He

Kahn rejected the easy road of imitation and visual charm. In projects like the Salk Institute, he invested new forms with primitive power and timelessness. In a world dominated by business as usual, few opportunities exist for the creation of architecture on this level. Kahn's commitment to it accounts for his relatively small output. Yale twice gave him the opportunity to build.

In his extraordinary 2003 documentary, My Architect, Kahn's son Nathaniel searches for his father - who died in 1974 when Nathaniel was 11 - among the buildings he left and the memories of those who knew him. Interviewed for the film, Stern tries to bring Kahn down to his own level, telling Nathaniel, "Don't put him up on some gigantic pedestal. . . Don't think that he was always trying to be a prince. He was very much trying to be a player. He wanted work, he wanted recognition. . . He was success-oriented." When Nathaniel asks, "Doesn't every architect?" Stern replies, "I can't speak for every architect." Nathaniel continues in voice-over that Kahn was half a million dollars in debt when he died, and that of all his projects, only the Salk Institute made money. Kahn was known to continue developing designs well after the likelihood of their realization or his payment for them had passed. An architect who worked for Kahn, William Huff, remembers him turning down a prospective client who wanted a colonial house designed, and suggesting Thomas Jefferson when she asked him to recommend a colonial architect. In a few years, Stern would have fit her bill. Twenty-eight years ago in the Journal New Society, Reyner Banham described Stern's "complete lack of scruple that enables him to perform equally well in any style (or caricature thereof) that the market will bear."

What would Kahn make of Stern today? Of seeing Stern's status as Yale's Dean of Architecture used to hawk ten million dollar tract mansions in the sales material for Villanova Heights, the Riverdale development of Stern's 10,000 to 15,000 square foot traditionally styled luxury homes? As quoted in Carter Wiseman's 2007 book, Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, William Huff says that Kahn "saw institutions as the important entities of man's cooperative interactions," and "loved Yale, where he found greatness as an institutional awareness - more so than his own alma mater," the University of Pennsylvania. Yale gave Kahn his first and last major commissions, for its Art Gallery extension and its Museum of British Art, and can claim much of the credit for creating his career. At the end of My Architect, in Kahn's Dhaka National Assembly Building, the architect Shamsul Wares movingly tells Nathaniel Kahn what an impossible gift his father had made to the poorest country in the world, for the asking. Kahn, he says, "has given us the institution for Democracy". Yale can take some of the credit for this. It's hard to believe this great institution can't find an engaged, pluralist dean for its school of architecture who wouldn't be so venal as to trade on its name, or use it to endorse self-serving preservation offenses. Stern seems a vestige of yesterday's world of self indulgence and unsustainable consumption, of Bush era deception and arrogance. Goldberger's 15 Central Park West pieces summon up the ghost of Herbert Muschamp, who in 1988 excoriated the previous boom's architects for abandoning social responsibility to become "Satan's decorators" and "hired flunkies".

Last year, Stern published The Philip Johnson Tapes, a book collecting his 1985 interviews of his teacher and "great friend". In it, Johnson says of Kahn, "I liked his work better than I liked him. . . . I never found him the great lovely guru-type. I couldn't stand all those long monologues about belief in truth. I can't stand truth. It gets so boring, you know, like social responsibility." Stern seems a bit bored by truth himself, letting Johnson turn questions about his fascist-leaning past into opportunities for lengthy self justification and whitewashing of his personal history into that of a "violent philo-Semite." Stern doesn't even call Johnson on this unreconstructed view of Germany in the 1930s: "I mean, Germany was being run down by the rich. The German Workers Party was the only solution. He Robert A.M. Stern, part 2

Stern's presumptuousness may owe something to the huge attention and acclaim that attended upon 15 Central Park West, the luxury condo he designed for the Zeckendorf Brothers. Based on classic prewar apartment buildings by Rosario Candela, the project is probably the biggest real estate phenomenon New York has ever seen. Quarterly New York real estate reports had to be adjusted to factor out the distorting influence of its astronomical sales. The website Curbed took to calling it the "limestone Jesus". At a time when New York developers were finally hiring serious architects like Richard Meier and Jean Nouvel to generate appeal, 15 CPW might have been seen as the ultimate vindication for architecture's claims to create value. For architects who take their profession seriously, though, it was disappointing that what made the project so successful wasn't the kind of quality that imagination can make out of thin air, but Stern's accurate sense of what investment bankers want, and how many times over the building's limestone cladding paid for itself.

For a Vanity Fair article on 15 Central Park West, Stern posed atop its concierge desk, weakly mimicking the classic image of an urbanely macho Robert Moses poised on an I-beam over the East River. Stern shares Moses' ego, if not his public mission, a distinction emphasized by this photo's gated setting. What lies beyond is for the privileged few.

Arnold Newman's 1959 photo serves as the cover for Robert Moses and the Modern City. Moses famously said "you can't make an omelet without breaking eggs." Unlike Stern's, his omelets were for everyone's consumption. What lies beyond is a public realm.

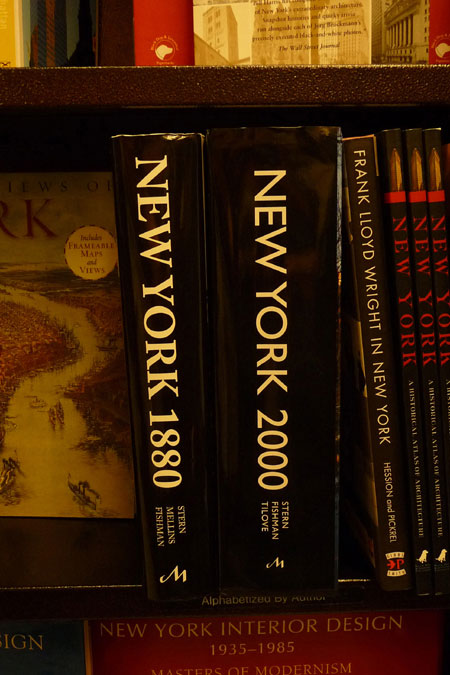

The normally balanced architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote two glowing reviews of 15 Central Park West. His 2007 New Yorker piece, "Past Perfect", pauses just long enough to ask, is "costume-drama luxury the best that our new century has to offer?" before getting back to the building's "exquisitely crafted marble trim." His 2008 Vanity Fair review, "The King of Central Park West", is likewise awestruck save for two sentences that find the building's exterior somewhat severe and its base less articulated than those of its neighbors. Both pieces bristle with celebrity names and dollar signs. Stern's enormous output fills many 9-pound books dedicated to his bland, pretty buildings for rich people. The sheer proliferation of his easily turned-out product becomes a concern when it spreads to the public urban realm as a sort of invasive species, climbing like kudzu up the side of the Woolworth Building or choking out the native specimens of a historic New Haven neighborhood.

A chummy interview of Stern by Goldberger is included in Robert A.M. Stern: Buildings & Projects 2004-2009. Like Stern, Goldberger graduated from Yale and has taught there. Stern's career is bound up in Yale, where as a student he formed lasting relationships with faculty members Vincent Scully and Philip Johnson.

Stern helped Scully research his 1962 book on Louis I. Kahn, the first book-length study of the architect, who also taught at Yale. Scully wrote of Kahn that he "had worked himself back to a point where he could begin to design architecture afresh, literally from the ground up, accepting no preconceptions, fashions or habits of design without questioning them profoundly. That 'great event,' so rare and precious in human history, when things were about to begin anew almost as if no things had ever been before, was on the way." If Stern ever read the book he helped Scully research, it had no effect on him.

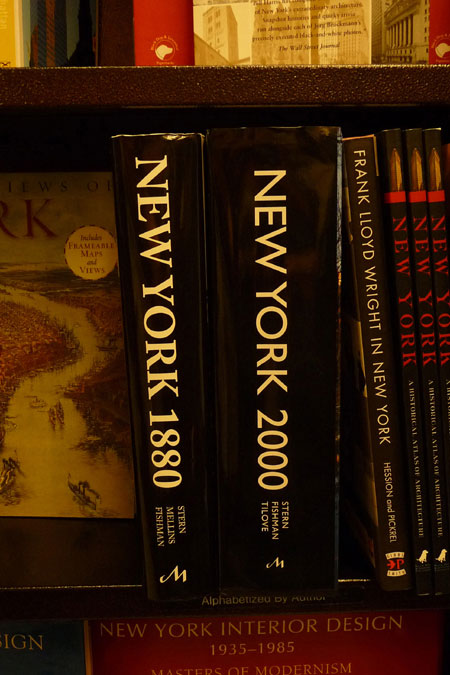

Stern's enormous output fills many 9-pound books dedicated to his bland, pretty buildings for rich people. The sheer proliferation of his easily turned-out product becomes a concern when it spreads to the public urban realm as a sort of invasive species, climbing like kudzu up the side of the Woolworth Building or choking out the native specimens of a historic New Haven neighborhood.

A chummy interview of Stern by Goldberger is included in Robert A.M. Stern: Buildings & Projects 2004-2009. Like Stern, Goldberger graduated from Yale and has taught there. Stern's career is bound up in Yale, where as a student he formed lasting relationships with faculty members Vincent Scully and Philip Johnson.

Stern helped Scully research his 1962 book on Louis I. Kahn, the first book-length study of the architect, who also taught at Yale. Scully wrote of Kahn that he "had worked himself back to a point where he could begin to design architecture afresh, literally from the ground up, accepting no preconceptions, fashions or habits of design without questioning them profoundly. That 'great event,' so rare and precious in human history, when things were about to begin anew almost as if no things had ever been before, was on the way." If Stern ever read the book he helped Scully research, it had no effect on him.

Kahn said architecture began "when the walls parted and the columns became." He preferred the bluntness of Paestum's ruins to the elegance of the Parthenon, finding them closer to the source of architecure's power. Architects like Stern see the past as something to be copied, often for easy profit, and as proof that the best that architecture has to offer is behind us. Their successive re-issues carry architecture ever farther from its generating force and original vitality.

Kahn's interest in the past is seen by some as making way for the postmodernism that Stern would pursue with such commercial success. In fact, Stern's approach to design may best be defined in contrast to Kahn's. Where Kahn finds inspiration in the past, Stern finds a crutch. Kahn's Art Gallery was the first building to break from Yale's neo-Gothic style. In 2006, Vincent Scully called the newly restored Art Gallery "our first modern building and our best." Nearly sixty years later, Stern is designing Yale's two new residential colleges in neo-Gothic style. If Stern stands for anything, it's the end of architectural history, as of the 1920s.

Kahn said architecture began "when the walls parted and the columns became." He preferred the bluntness of Paestum's ruins to the elegance of the Parthenon, finding them closer to the source of architecure's power. Architects like Stern see the past as something to be copied, often for easy profit, and as proof that the best that architecture has to offer is behind us. Their successive re-issues carry architecture ever farther from its generating force and original vitality.

Kahn's interest in the past is seen by some as making way for the postmodernism that Stern would pursue with such commercial success. In fact, Stern's approach to design may best be defined in contrast to Kahn's. Where Kahn finds inspiration in the past, Stern finds a crutch. Kahn's Art Gallery was the first building to break from Yale's neo-Gothic style. In 2006, Vincent Scully called the newly restored Art Gallery "our first modern building and our best." Nearly sixty years later, Stern is designing Yale's two new residential colleges in neo-Gothic style. If Stern stands for anything, it's the end of architectural history, as of the 1920s.

Kahn rejected the easy road of imitation and visual charm. In projects like the Salk Institute, he invested new forms with primitive power and timelessness. In a world dominated by business as usual, few opportunities exist for the creation of architecture on this level. Kahn's commitment to it accounts for his relatively small output. Yale twice gave him the opportunity to build.

In his extraordinary 2003 documentary, My Architect, Kahn's son Nathaniel searches for his father - who died in 1974 when Nathaniel was 11 - among the buildings he left and the memories of those who knew him. Interviewed for the film, Stern tries to bring Kahn down to his own level, telling Nathaniel, "Don't put him up on some gigantic pedestal. . . Don't think that he was always trying to be a prince. He was very much trying to be a player. He wanted work, he wanted recognition. . . He was success-oriented." When Nathaniel asks, "Doesn't every architect?" Stern replies, "I can't speak for every architect." Nathaniel continues in voice-over that Kahn was half a million dollars in debt when he died, and that of all his projects, only the Salk Institute made money. Kahn was known to continue developing designs well after the likelihood of their realization or his payment for them had passed. An architect who worked for Kahn, William Huff, remembers him turning down a prospective client who wanted a colonial house designed, and suggesting Thomas Jefferson when she asked him to recommend a colonial architect. In a few years, Stern would have fit her bill. Twenty-eight years ago in the Journal New Society, Reyner Banham described Stern's "complete lack of scruple that enables him to perform equally well in any style (or caricature thereof) that the market will bear."

What would Kahn make of Stern today? Of seeing Stern's status as Yale's Dean of Architecture used to hawk ten million dollar tract mansions in the sales material for Villanova Heights, the Riverdale development of Stern's 10,000 to 15,000 square foot traditionally styled luxury homes? As quoted in Carter Wiseman's 2007 book, Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, William Huff says that Kahn "saw institutions as the important entities of man's cooperative interactions," and "loved Yale, where he found greatness as an institutional awareness - more so than his own alma mater," the University of Pennsylvania. Yale gave Kahn his first and last major commissions, for its Art Gallery extension and its Museum of British Art, and can claim much of the credit for creating his career. At the end of My Architect, in Kahn's Dhaka National Assembly Building, the architect Shamsul Wares movingly tells Nathaniel Kahn what an impossible gift his father had made to the poorest country in the world, for the asking. Kahn, he says, "has given us the institution for Democracy". Yale can take some of the credit for this. It's hard to believe this great institution can't find an engaged, pluralist dean for its school of architecture who wouldn't be so venal as to trade on its name, or use it to endorse self-serving preservation offenses. Stern seems a vestige of yesterday's world of self indulgence and unsustainable consumption, of Bush era deception and arrogance. Goldberger's 15 Central Park West pieces summon up the ghost of Herbert Muschamp, who in 1988 excoriated the previous boom's architects for abandoning social responsibility to become "Satan's decorators" and "hired flunkies".

Last year, Stern published The Philip Johnson Tapes, a book collecting his 1985 interviews of his teacher and "great friend". In it, Johnson says of Kahn, "I liked his work better than I liked him. . . . I never found him the great lovely guru-type. I couldn't stand all those long monologues about belief in truth. I can't stand truth. It gets so boring, you know, like social responsibility." Stern seems a bit bored by truth himself, letting Johnson turn questions about his fascist-leaning past into opportunities for lengthy self justification and whitewashing of his personal history into that of a "violent philo-Semite." Stern doesn't even call Johnson on this unreconstructed view of Germany in the 1930s: "I mean, Germany was being run down by the rich. The German Workers Party was the only solution. He

Kahn rejected the easy road of imitation and visual charm. In projects like the Salk Institute, he invested new forms with primitive power and timelessness. In a world dominated by business as usual, few opportunities exist for the creation of architecture on this level. Kahn's commitment to it accounts for his relatively small output. Yale twice gave him the opportunity to build.

In his extraordinary 2003 documentary, My Architect, Kahn's son Nathaniel searches for his father - who died in 1974 when Nathaniel was 11 - among the buildings he left and the memories of those who knew him. Interviewed for the film, Stern tries to bring Kahn down to his own level, telling Nathaniel, "Don't put him up on some gigantic pedestal. . . Don't think that he was always trying to be a prince. He was very much trying to be a player. He wanted work, he wanted recognition. . . He was success-oriented." When Nathaniel asks, "Doesn't every architect?" Stern replies, "I can't speak for every architect." Nathaniel continues in voice-over that Kahn was half a million dollars in debt when he died, and that of all his projects, only the Salk Institute made money. Kahn was known to continue developing designs well after the likelihood of their realization or his payment for them had passed. An architect who worked for Kahn, William Huff, remembers him turning down a prospective client who wanted a colonial house designed, and suggesting Thomas Jefferson when she asked him to recommend a colonial architect. In a few years, Stern would have fit her bill. Twenty-eight years ago in the Journal New Society, Reyner Banham described Stern's "complete lack of scruple that enables him to perform equally well in any style (or caricature thereof) that the market will bear."

What would Kahn make of Stern today? Of seeing Stern's status as Yale's Dean of Architecture used to hawk ten million dollar tract mansions in the sales material for Villanova Heights, the Riverdale development of Stern's 10,000 to 15,000 square foot traditionally styled luxury homes? As quoted in Carter Wiseman's 2007 book, Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, William Huff says that Kahn "saw institutions as the important entities of man's cooperative interactions," and "loved Yale, where he found greatness as an institutional awareness - more so than his own alma mater," the University of Pennsylvania. Yale gave Kahn his first and last major commissions, for its Art Gallery extension and its Museum of British Art, and can claim much of the credit for creating his career. At the end of My Architect, in Kahn's Dhaka National Assembly Building, the architect Shamsul Wares movingly tells Nathaniel Kahn what an impossible gift his father had made to the poorest country in the world, for the asking. Kahn, he says, "has given us the institution for Democracy". Yale can take some of the credit for this. It's hard to believe this great institution can't find an engaged, pluralist dean for its school of architecture who wouldn't be so venal as to trade on its name, or use it to endorse self-serving preservation offenses. Stern seems a vestige of yesterday's world of self indulgence and unsustainable consumption, of Bush era deception and arrogance. Goldberger's 15 Central Park West pieces summon up the ghost of Herbert Muschamp, who in 1988 excoriated the previous boom's architects for abandoning social responsibility to become "Satan's decorators" and "hired flunkies".

Last year, Stern published The Philip Johnson Tapes, a book collecting his 1985 interviews of his teacher and "great friend". In it, Johnson says of Kahn, "I liked his work better than I liked him. . . . I never found him the great lovely guru-type. I couldn't stand all those long monologues about belief in truth. I can't stand truth. It gets so boring, you know, like social responsibility." Stern seems a bit bored by truth himself, letting Johnson turn questions about his fascist-leaning past into opportunities for lengthy self justification and whitewashing of his personal history into that of a "violent philo-Semite." Stern doesn't even call Johnson on this unreconstructed view of Germany in the 1930s: "I mean, Germany was being run down by the rich. The German Workers Party was the only solution. He Robert A.M. Stern, part 1

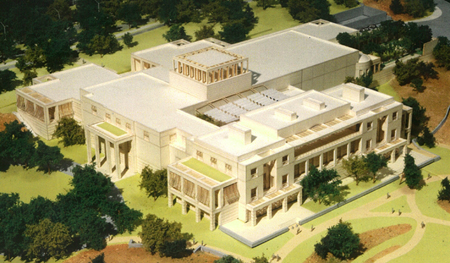

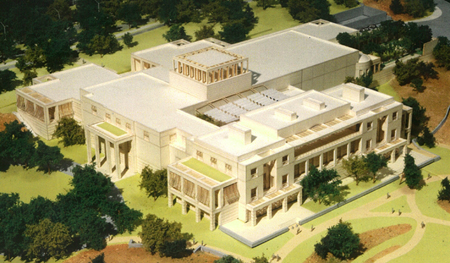

A rendering shows the main entrance of Robert A.M. Stern's George W. Bush Presidential Center. "I'm not considered avant-garde because I'm not avant-garde," Stern says, "but there is a parallel world out there - of excellence."

Earlier this month Robert A.M. Stern presented his preliminary design of the the Bush Library. Stern has just the right attributes to be his fellow Yale alum's architect: conservativism's DNA-inscribed commitment to tradition, and an inability to refuse any commission, no matter how unsavory. His building is the backward-gazing counterpart to the Polshek Partnership's bridge-to-tomorrow Clinton Library.

A muddled Bush Presidential Center is revealed in this model view. Stern's design calls for red brick and limestone facing.

The project will be built on the Campus of Dallas's Southern Methodist University, where some faculty have objected to association with "a pre-emptive war based on false premises" and "a legacy of massive violence, destruction, and death . . . in dismissal of broad international opinion." The Center comes to SMU attached to the "Freedom Institute", a conservative think tank the presence of which has further angered faculty. As reported in the New York Times Magazine, "Everything about the planned institute reminds them of what they detested about the Bush administration. It will proselytize rather than explore: a letter sent to universities bidding for the Bush center stipulated that the institute would, among other things, 'further the domestic and international goals of the Bush administration.' ”

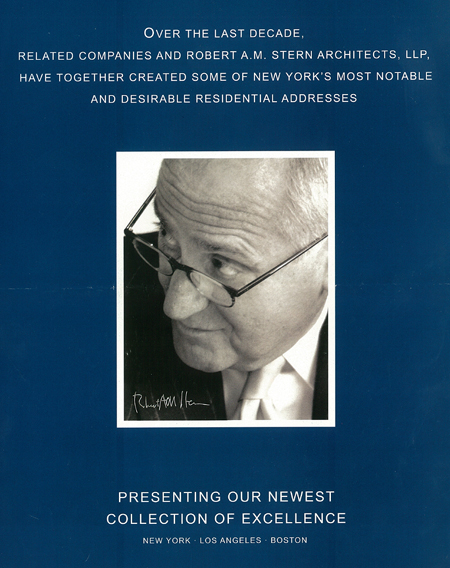

For Stern, the Library commission came as his profile reached dizzying new heights, primarily because of the phenomenal commercial success of his luxury condominium design for 15 Central Park West. The development's sales were enough to skew Manhattan real estate statistics for months on end. In 2008 he was also awarded the Vincent Scully Prize, named for his old teacher, by the National Building Museum. In December of 2007, the New York Times published a highly flattering appraisal of his turn as Dean of Yale's School of Architecture, in which Reed Kroloff is quoted to say, "Bob Stern may be the best school of architecture dean in the United States."

A standard reference among preservationists, Stern's unparalleled five volume study of New York architectural history bolsters his reputation as a scholar.

It was Kroloff who had famously called Stern "the suede-loafered sultan of suburban retrotecture" in a 1998 Architecture magazine editorial about his appointment. The Times piece plays up this turnabout, but in fact Kroloff's loafer throwing had been a preamble to support for Yale's decision; his 1998 piece went on to say of Stern, "he is a teacher, scholar, and practitioner whose passion for and dedication to architecture are beyond question." Kroloff also accurately predicted that Stern would be "smart enough not to try imposing an esthetic agenda on a school that has always valued pluralism." While Stern's architecture gets little critical respect, his dedication and scholarship have indeed long been viewed as unassailable. Several of his recent projects, however, have seriously hurt his reputation among preservationists.

Yale's Hammond Hall has stood since 1904. While a study found that it could be easily adapted to new use, the much loved Beaux Arts building is one of a dozen to be razed for Stern's new dormitories.

Stern's designs for two new Yale dormitory complexes have particularly rankled preservationists this summer. The New Haven Preservation Trust and the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation unsuccessfully petitioned Yale to save seven historic buildings that are in the path of Stern's plans. Characteristically, his new gothic buildings will substitute false antiquity for the real thing, an approach that's oblivious to both preservation principals and sustainability. Stern's dismissal of what is authentic in favor of make-believe meshes nicely with his past service on the Disney Company's board of directors.

The just-completed Superior Ink Condominium

On West Street in Greenwich Village, Stern's Superior Ink Condominium would be entitled to its name had it adapted or added onto the original 1919 Superior Ink Building rather than razing it. The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation had unsuccessfully lobbied the Landmarks Preservation Commission to extend the Greenwich Village Historic District to include the old building, which it viewed as a rare remaining trace of its neighborhood's industrial past. While demolition of an older building to make way for a larger new one is business as usual in New York, Stern's replacement is distinguished by how much it looks like an escapee from one of the postmodern development ghettos just across the Hudson. Meanwhile, not far up the old working waterfront from Superior Ink, the High Line Park is a glowing example of what imagination can make of a modest industrial relic, while preserving a neighborhood's unique sense of place.

In October of 2007, the Related Companies ran an 8-page ad in the New York Times Magazine dedicated to Stern and his luxury condominium towers, including The Harrison on Manahattan's Upper West Side. In 2006, the facade of Manhattan's historic Dakota Stable building had its ornamental details jackhammered off by dark of night to keep it from being landmarked, clearing the way for sale of the property to Related and construction of The Harrison. Stern had developed a fullblown design for the condo before the Dakota Stable was defaced.

On Manhattan's Upper West Side, preservation groups that had welcomed Stern's efforts to protect 2 Columbus Circle were reportedly shocked to learn that he had kept them in the dark about his client Related's intention to demolish the historic Dakota Stable. Even as they lobbied the Landmarks Commission to protect the building, Stern was designing its replacement, yet another bland luxury condo. While in contract to sell the Stable to Related, its owner rushed to deface it - literally by dark of night - as soon as the Landmarks Commission signalled an intent to designate the building. The strategy succeeded in preventing landmark designation and protection. Stern is quoted in the New York Times as saying that the nighttime demolition created "a controversial and awkward moment", adding "I don't like to tear anything down if I don't have to."

Stern's design for a hotel and condominium at 99 Church Street, center, would share a block with - and tower over - the Woolworth Building, at right. His involvement in the project proves that to Stern, no building is so great that one of his own isn't better.

Stern has proven quite capable of doing harm without tearing anything down. His 912 foot tower design for 99 Church Street, currently on hold, would overshadow the 792 foot Woolworth Building, one of the most significant buildings in skyscraper history. As David Dunlap wrote in the New York Times, "the Woolworth Building, already hemmed in by the new 58-story Barclay Tower across Barclay Street, will never soar the same." Unlike Costas Kondylis, the Barclay Tower's designer and Trump house-architect, Stern sets great store by historic sensitivity. His office's website proclaims that "our firm's practice is premised on the belief that the public is entitled to buildings that do not, by their very being, threaten the aesthetic and cultural values of the buildings around them," and speaks of "entering into a dialogue with the past and with the spirit of the places in which we build."

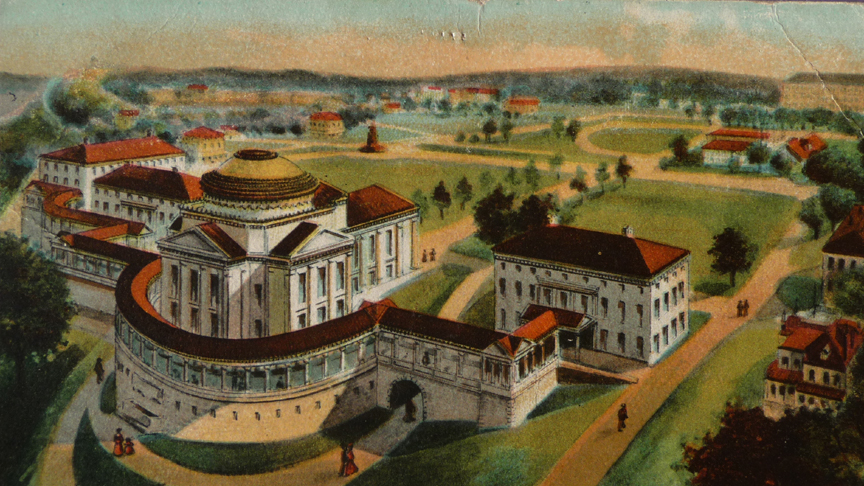

Stanford White envisioned his Gould Memorial Library as the centerpiece of NYU's north campus. Stern had other ideas.